| |

| Named after | George Ellery Hale |

|---|---|

| Part of | Palomar Observatory |

| Location(s) | Palomar Mountain, California, US |

| Coordinates | 33°21′23″N 116°51′54″WCoordinates: 33°21′23″N 116°51′54″W |

| Altitude | 1,713 m (5,620 ft) |

| Built | 1936 –1948 |

| First light | January 26, 1949, 10:06 pm PST |

| Discovered | Caliban, Sycorax, Jupiter LI |

| Telescope style | optical telescope reflecting telescope |

| Diameter | 200 in (5.1 m) |

| Collecting area | 31,000 sq in (20 m2) |

| Focal length | 16.76 m (55 ft 0 in) |

| Mounting | Equatorial mount |

| Website | www |

The Hale Telescope is a 200-inch (5.1 m), f/3.3 reflecting telescope at the Palomar Observatory in California, US, named after astronomer George Ellery Hale. With funding from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1928, he orchestrated the planning, design, and construction of the observatory, but with the project ending up taking 20 years he did not live to see its commissioning. The Hale was groundbreaking for its time, with double the diameter of the second-largest telescope, and pioneered many new technologies in telescope mount design and in the design and fabrication of its large aluminum coated "honeycomb" low thermal expansion Pyrex mirror. It was completed in 1949 and is still in active use.

The Hale Telescope represented the technological limit in building large optical telescopes for over 30 years. It was the largest telescope in the world from its construction in 1949 until the Russian BTA-6 was built in 1976, and the second largest until the construction of the Keck Observatory Keck 1 in 1993.

History

Base of the tube

Crab Nebula, 1959

Hale supervised the building of the telescopes at the Mount Wilson Observatory with grants from the Carnegie Institution of Washington:

the 60-inch (1.5 m) telescope in 1908 and the 100-inch (2.5 m)

telescope in 1917. These telescopes were very successful, leading to the

rapid advance in understanding of the scale of the Universe through the 1920s, and demonstrating to visionaries like Hale the need for even larger collectors.

The chief optical designer for Hale's previous 100-inch telescope was George Willis Ritchey, who intended the new telescope to be of Ritchey–Chrétien

design. Compared to the usual parabolic primary, this design would have

provided sharper images over a larger usable field of view. However,

Ritchey and Hale had a falling-out. With the project already late and

over budget, Hale refused to adopt the new design, with its complex

curvatures, and Ritchey left the project. The Mount Palomar Hale

Telescope turned out to be the last world-leading telescope to have a

parabolic primary mirror.

In 1928 Hale secured a grant of $6 million from the Rockefeller Foundation for "the construction of an observatory, including a 200-inch reflecting telescope" to be administered by the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), of which Hale was a founding member. In the early 1930s, Hale selected a site at 1,700 m (5,600 ft) on Palomar Mountain in San Diego County, California, US, as the best site, and less likely to be affected by the growing light pollution problem in urban centers like Los Angeles. The Corning Glass Works

was assigned the task of making a 200-inch (5.1 m) primary mirror.

Construction of the observatory facilities and dome started in 1936, but

because of interruptions caused by World War II, the telescope was not completed until 1948 when it was dedicated.

Due to slight distortions of images, corrections were made to the

telescope throughout 1949. It became available for research in 1950.

The 200-inch (510 cm) telescope saw first light on January 26, 1949, at 10:06 pm PST under the direction of American astronomer Edwin Powell Hubble, targeting NGC 2261, an object also known as Hubble's Variable Nebula. The photographs made then were published in the astronomical literature and in the May 7, 1949 issue of Collier's Magazine.

The telescope continues to be used every clear night for

scientific research by astronomers from Caltech and their operating

partners, Cornell University, the University of California, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. It is equipped with modern optical and infrared array imagers, spectrographs, and an adaptive optics system. It has also used lucky cam imaging, which in combination with adaptive optics pushed the mirror close to its theoretical resolution for certain types of viewing.

One of the Corning Labs' glass test blanks for the Hale was used for the C. Donald Shane telescope's 120-inch (300 cm) primary mirror.

The collecting area of the mirror is about 31,000 square inches (20 square meters).

Components

The

Hale was not just big, it was better, and not just but better but

combined breakthrough technologies including a new lower expansion glass

from Corning, a newly invented Serruier truss, and vapor deposited

aluminum.

Mounting structures

The Hale Telescope uses a special type of equatorial mount

called a "horseshoe mount", a modified yoke mount that replaces the

polar bearing with an open "horseshoe" structure that gives the

telescope full access to the entire sky, including Polaris and stars near it. The optical tube assembly (OTA) uses a Serrurier truss, then newly invented by Mark U. Serrurier of Caltech in Pasadena in 1935, designed to flex in such a way as to keep all of the optics in alignment. Theodore von Karman designed the lubrication system to avoid potential issues with turbulence during tracking.

Left: The 200-inch (508 cm) Hale Telescope inside on its equatorial mount.

Right: Principle of operation of a Serrurier truss similar to that of the Hale Telescope compared to a simple truss. For clarity, only the top and bottom structural elements are shown. Red and green lines denote elements under tension and compression, respectively.

Right: Principle of operation of a Serrurier truss similar to that of the Hale Telescope compared to a simple truss. For clarity, only the top and bottom structural elements are shown. Red and green lines denote elements under tension and compression, respectively.

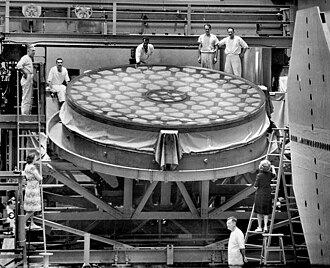

200-inch mirror

The

5 meter (16 ft. 8 in.) mirror in December 1945 at the Caltech Optical

Shop when grinding resumed following World War 2. The honeycomb support

structure on the back of the mirror is visible through the surface.

Originally, the Hale Telescope was going to use a primary mirror of fused quartz manufactured by General Electric, but instead the primary mirror was cast in 1934 at Corning Glass Works in New York State using Corning's then new material called Pyrex (borosilicate glass).

Pyrex was chosen for its low expansion qualities so the large mirror

would not distort the images produced when it changed shape due to

temperature variations (a problem that plagued earlier large

telescopes).

Entrance door to 200 inch Hale telescope dome

The mirror was cast in a mold with 36 raised mold blocks (similar in shape to a waffle iron). This created a honeycomb mirror

that cut the amount of Pyrex needed down from over 40 short tons (36 t)

to just 20 short tons (18 t), making a mirror that would cool faster in

use and have multiple "mounting points" on the back to evenly

distribute its weight (note – see external links 1934 article for

drawings). The shape of a central hole was also part of the mold so light could pass through the finished mirror when it was used in a Cassegrain configuration (a Pyrex plug for this hole was also made to be used during the grinding and polishing process).

While the glass was being poured into the mold during the first attempt

to cast the 200-inch mirror, the intense heat caused several of the

molding blocks to break loose and float to the top, ruining the mirror.

The defective mirror was used to test the annealing process. After the

mold was re-engineered, a second mirror was successfully cast.

After cooling several months, the finished mirror blank was transported by rail to Pasadena, California.

Once in Pasadena the mirror was transferred from the rail flat car to a

specially designed semi-trailer for road transport to where it would be

polished. In the optical shop in Pasadena (now the Synchrotron building at Caltech) standard telescope mirror making

techniques were used to turn the flat blank into a precise concave

parabolic shape, although they had to be executed on a grand scale. A

special 240 in (6.1 m) 25,000 lb (11 t) mirror cell jig was constructed which could employ five different motions when the mirror was ground and polished.

Over 13 years almost 10,000 lb (4.5 t) of glass was ground and polished

away reducing the weight of the mirror to 14.5 short tons (13.2 t). The

mirror was coated (and still is re-coated every 18–24 months) with a

reflective aluminum surface using the same aluminum vacuum-deposition

process invented in 1930 by Caltech physicist and astronomer John

Strong.

The Hale's 200 in (510 cm) mirror was near the technological limit of a primary mirror made of a single rigid piece of glass.

Using a monolithic mirror much larger than the 5-meter Hale or 6-meter

BTA-6 is prohibitively expensive due to the cost of both the mirror, and

the massive structure needed to support it. A mirror beyond that size

would also sag slightly under its own weight as the telescope is rotated

to different positions, changing the precision shape of the surface, which must be accurate to within 2 millionths of an inch (50 nm).

Modern telescopes over 9 meters use a different mirror design to solve

this problem, with either a single thin flexible mirror or a cluster of

smaller segmented mirrors, whose shape is continuously adjusted by a computer-controlled active optics system using actuators built into the mirror support cell.

Dome

The moving weight of the upper dome is about 1000 US tons, and can rotate on wheels. The dome doors weigh 125 tons each.

The dome is made of welded steel plates about 10 mm thick.

Observations and research

Dome of the 200-inch aperture Hale telescope

The first observation of the Hale telescope was of NGC 2261 on January 26, 1949.

Halley's Comet (1P) upcoming 1986 approach to the Sun was first detected by astronomers David C. Jewitt and G. Edward Danielson on 16 October 1982 using the 200-inch Hale telescope equipped with a CCD camera.

Two moons of the planet Uranus were discovered in September 1997, in addition to the planet's 15 other known moons at that time. One was Caliban (S/1997 U 1), which was discovered on 6 September 1997 by Brett J. Gladman, Philip D. Nicholson, Joseph A. Burns, and John J. Kavelaars using the 200-inch Hale telescope. The other Uranian moon discovered then is Sycorax (initial designation S/1997 U 2) and was also discovered using the 200 inch Hale telescope.

In 1999, astronomers used a near-infrared camera and adaptive

optics to take some of the best Earth-surface based images of planet

Neptune up to that time. The images were sharp enough to identify clouds in the ice giant's atmosphere.

The Cornell Mid-Infrared Asteroid Spectroscopy (MIDAS) survey used the Hale Telescope with a spectrograph to study spectra from 29 asteroids. An example of a result from that study, is that the asteroid 3 Juno was determined to have average radius of 135.7±11 km using the infrared data.

In 2009, using a coronograph, the Hale telescope was used to discover the star Alcor B, which is a companion to Alcor in the famous Big Dipper constellation.

In 2010, a new satellite of planet Jupiter was discovered with the 200-inch Hale, called S/2010 J 1 and later named Jupiter LI.

In October 2017 the Hale telescope was able to record the spectrum of the first recognized interstellar object, 1I/2017 U1 ("ʻOumuamua"); while not specific mineral was identified it showed the visitor had a reddish surface color.

Direct imaging of exoplanets

Up until the year 2010, telescopes could only directly image

exoplanets under exceptional circumstances. Specifically, it is easier

to obtain images when the planet is especially large (considerably

larger than Jupiter), widely separated from its parent star, and hot so that it emits intense infrared radiation. However, in 2010 a team from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory demonstrated that a vortex coronagraph could enable small scopes to directly image planets. They did this by imaging the previously imaged HR 8799 planets using just a 1.5 m portion of the Hale Telescope.

Direct image of exoplanets around the star HR8799 using a vortex coronagraph on a 1.5m portion of the Hale Telescope

Comparison

Size comparison of the Hale Telescope (upper left, blue) to some modern and upcoming extremely large telescopes

The Hale had four times the light-collecting area of the

second-largest scope when it was commissioned in 1949. Other

contemporary telescopes were the Hooker Telescope at the Mount Wilson Observatory and the Otto Struve Telescope at the McDonald Observatory.

| # | Name / Observatory |

Image | Aperture | Altitude | First Light |

Special advocate(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hale Telescope Palomar Obs. |

200-inch 508 cm |

1713 m (5620 ft) |

1949 | George Ellery Hale John D. Rockefeller Edwin Hubble | |

| 2 | Hooker Telescope Mount Wilson Obs. |

100-inch 254 cm |

1742 m (5715 ft) |

1917 | George Ellery Hale Andrew Carnegie | |

| 3 | Otto Struve Telescope McDonald Obs. |

82-inch 210 cm |

2070 m (6791 ft) |

1939 | Otto Struve |