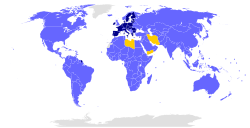

State parties

Signatories

Parties covered by EU ratification

| |

| Drafted | 30 November – 12 December 2015 in Le Bourget, France |

|---|---|

| Signed | 22 April 2016 |

| Location | New York City, United States |

| Sealed | 12 December 2015 |

| Effective | 4 November 2016 |

| Condition | Ratification and accession by 55 UNFCCC parties, accounting for 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions |

| Signatories | 195 |

| Parties | 187 |

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

| Languages | Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian, Spanish and Afrikaans |

The Paris Agreement (French: Accord de Paris) is an agreement within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), dealing with greenhouse-gas-emissions mitigation, adaptation, and finance, signed in 2016. The agreement's language was negotiated by representatives of 196 state parties at the 21st Conference of the Parties of the UNFCCC in Le Bourget, near Paris, France, and adopted by consensus on 12 December 2015. As of March 2019, 195 UNFCCC members have signed the agreement, and 187 have become party to it.

The Paris Agreement's long-term temperature goal is to keep the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels; and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 °C, recognizing that this would substantially reduce the risks and impacts of climate change. This should be done by peaking emissions as soon as possible, in order to "achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases" in the second half of the 21st century. It also aims to increase the ability of parties to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change, and make "finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development."

Under the Paris Agreement, each country must determine, plan, and regularly report on the contribution that it undertakes to mitigate global warming. No mechanism forces a country to set a specific target by a specific date, but each target should go beyond previously set targets. In June 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump announced his intention to withdraw the United States from the agreement. Under the agreement, the earliest effective date of withdrawal for the U.S. is November 2020, shortly before the end of President Trump's current term. In practice, changes in United States policy that are contrary to the Paris Agreement have already been put in place.

Content

Aims

The

aim of the agreement is to decrease global warming described in its

Article 2, "enhancing the implementation" of the UNFCCC through:

(a) Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change;

(b) Increasing the ability to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change and foster climate resilience and low greenhouse gas emissions development, in a manner that does not threaten food production;

(c) Making finance flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

This strategy involved energy and climate policy including the so-called 20/20/20 targets, namely the reduction of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 20%, the increase of renewable energy's market share to 20%, and a 20% increase in energy efficiency.

Countries furthermore aim to reach "global peaking of greenhouse

gas emissions as soon as possible". The agreement has been described as

an incentive for and driver of fossil fuel divestment.

The Paris deal is the world's first comprehensive climate agreement.

Nationally determined contributions

Global carbon dioxide emissions by jurisdiction.

Contributions each individual country should make to achieve the

worldwide goal are determined by all countries individually and are

called nationally determined contributions (NDCs).

Article 3 requires them to be "ambitious", "represent a progression

over time" and set "with the view to achieving the purpose of this

Agreement". The contributions should be reported every five years and

are to be registered by the UNFCCC Secretariat. Each further ambition should be more ambitious than the previous one, known as the principle of 'progression'. Countries can cooperate and pool their nationally determined contributions. The Intended Nationally Determined Contributions pledged during the 2015 Climate Change Conference serve—unless provided otherwise—as the initial Nationally determined contribution.

The level of NDCs set by each country

will set that country's targets. However the 'contributions' themselves

are not binding as a matter of international law, as they lack the

specificity, normative character, or obligatory language necessary to

create binding norms. Furthermore, there will be no mechanism to force a country to set a target in their NDC by a specific date and no enforcement if a set target in an NDC is not met. There will be only a "name and shame" system or as János Pásztor, the U.N. assistant secretary-general on climate change, told CBS News (US), a "name and encourage" plan.

As the agreement provides no consequences if countries do not meet

their commitments, consensus of this kind is fragile. A trickle of

nations exiting the agreement could trigger the withdrawal of more

governments, bringing about a total collapse of the agreement.

The NDC Partnership

was launched at COP22 in Marrakesh to enhance cooperation so that

countries have access to the technical knowledge and financial support

they need to achieve large-scale climate and sustainable development

targets. The NDC Partnership is guided by a Steering Committee composed of developed and developing nations and international institutions, and facilitated by a Support Unit hosted by World Resources Institute

and based in Washington, DC and Bonn, Germany. The NDC Partnership is

co-chaired by the governments of Costa Rica and the Netherlands and

includes 93 member countries,21 institutional partners and ten associate members.

Effects on global temperature

The

negotiators of the agreement, however, stated that the NDCs and the

target of no more than 2 °C increase were insufficient; instead, a

target of 1.5 °C maximum increase is required, noting "with concern that

the estimated aggregate greenhouse gas emission levels in 2025 and 2030

resulting from the intended nationally determined contributions do not

fall within least-cost 2 °C scenarios but rather lead to a projected

level of 55 gigatonnes in 2030", and recognizing furthermore "that much

greater emission reduction efforts will be required in order to hold the

increase in the global average temperature to below 2 °C by reducing

emissions to 40 gigatonnes or to 1.5 °C."

Though not the sustained temperatures over the long term that the

Agreement addresses, in the first half of 2016 average temperatures

were about 1.3 °C (2.3 degrees Fahrenheit) above the average in 1880,

when global record-keeping began.

When the agreement achieved enough signatures to cross the threshold on 5 October 2016, US President Barack Obama

claimed that "Even if we meet every target ... we will only get to part

of where we need to go." He also said that "this agreement will help

delay or avoid some of the worst consequences of climate change. It will

help other nations ratchet down their emissions over time, and set

bolder targets as technology advances, all under a strong system of

transparency that allows each nation to evaluate the progress of all

other nations."

Global stocktake

Map

of cumulative per capita anthropogenic atmospheric CO2 emissions by

country. Cumulative emissions include land use change, and are measured

between the years 1950 and 2000.

The global stocktake will kick off with a "facilitative dialogue" in

2018. At this convening, parties will evaluate how their NDCs stack up

to the nearer-term goal of peaking global emissions and the long-term

goal of achieving net zero emissions by the second half of this century.

The implementation of the agreement by all member countries

together will be evaluated every 5 years, with the first evaluation in

2023. The outcome is to be used as input for new nationally determined

contributions of member states.

The stocktake will not be of contributions/achievements of individual

countries but a collective analysis of what has been achieved and what

more needs to be done.

The stocktake works as part of the Paris Agreement's effort to

create a "ratcheting up" of ambition in emissions cuts. Because analysts

have agreed that the current NDCs will not limit rising temperatures

below 2 degrees Celsius, the global stocktake reconvenes parties to

assess how their new NDCs must evolve so that they continually reflect a

country's "highest possible ambition".

While ratcheting up the ambition of NDCs is a major aim of the

global stocktake, it assesses efforts beyond mitigation. The 5-year

reviews will also evaluate adaptation, climate finance provisions, and

technology development and transfer.

Structure

The

Paris Agreement has a 'bottom up' structure in contrast to most

international environmental law treaties, which are 'top down',

characterised by standards and targets set internationally, for states

to implement. Unlike its predecessor, the Kyoto Protocol,

which sets commitment targets that have legal force, the Paris

Agreement, with its emphasis on consensus-building, allows for voluntary

and nationally determined targets.

The specific climate goals are thus politically encouraged, rather than

legally bound. Only the processes governing the reporting and review of

these goals are mandated under international law. This structure is

especially notable for the United States—because there are no legal

mitigation or finance targets, the agreement is considered an "executive

agreement rather than a treaty". Because the UNFCCC treaty of 1992

received the consent of the Senate, this new agreement does not require

further legislation from Congress for it to take effect.

Another key difference between the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto

Protocol is their scopes. While the Kyoto Protocol differentiated

between Annex-1 and non-Annex-1 countries, this bifurcation is blurred

in the Paris Agreement, as all parties will be required to submit

emissions reductions plans.

While the Paris Agreement still emphasizes the principle of "Common but

Differentiated Responsibility and Respective Capabilities"—the

acknowledgement that different nations have different capacities and

duties to climate action—it does not provide a specific division between

developed and developing nations.

It therefore appears that negotiators will have to continue to deal

with this issue in future negotiation rounds, even though the discussion

on differentiation may take on a new dynamic.

Mitigation provisions and carbon markets

Article 6 has been flagged as containing some of the key provisions of the Paris Agreement. Broadly, it outlines the cooperative approaches

that parties can take in achieving their nationally determined carbon

emissions reductions. In doing so, it helps establish the Paris

Agreement as a framework for a global carbon market.

Linkage of trading systems and international transfer of mitigation outcomes (ITMOs)

Paragraphs 6.2

and 6.3 establish a framework to govern the international transfer of

mitigation outcomes (ITMOs). The Agreement recognizes the rights of

Parties to use emissions reductions outside of their own jurisdiction

toward their NDC, in a system of carbon accounting and trading.

This provision requires the "linkage" of various carbon emissions

trading systems—because measured emissions reductions must avoid

"double counting", transferred mitigation outcomes must be recorded as a

gain of emission units for one party and a reduction of emission units

for the other.

Because the NDCs, and domestic carbon trading schemes, are

heterogeneous, the ITMOs will provide a format for global linkage under

the auspices of the UNFCCC.

The provision thus also creates a pressure for countries to adopt

emissions management systems—if a country wants to use more

cost-effective cooperative approaches to achieve their NDCs, they will need to monitor carbon units for their economies.

Sustainable Development Mechanism

Paragraphs 6.4-6.7 establish a mechanism "to contribute to the mitigation of greenhouse gases and support sustainable development".

Though there is no specific name for the mechanism as yet, many Parties

and observers have informally coalesced around the name "Sustainable

Development Mechanism" or "SDM". The SDM is considered to be the successor to the Clean Development Mechanism, a flexible mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol, by which parties could collaboratively pursue emissions reductions for their Intended Nationally Determined Contributions.

The Sustainable Development Mechanism lays the framework for the future

of the Clean Development Mechanism post-Kyoto (in 2020).

In its basic aim, the SDM will largely resemble the Clean

Development Mechanism, with the dual mission to 1. contribute to global

GHG emissions reductions and 2. support sustainable development.

Though the structure and processes governing the SDM are not yet

determined, certain similarities and differences from the Clean

Development Mechanism can already be seen. Notably, the SDM, unlike the

Clean Development Mechanism, will be available to all parties as opposed

to only Annex-1 parties, making it much wider in scope.

Since the Kyoto Protocol went into force, the Clean Development

Mechanism has been criticized for failing to produce either meaningful

emissions reductions or sustainable development benefits in most

instances.

It has also suffered from the low price of Certified Emissions

Reductions (CERs), creating less demand for projects. These criticisms

have motivated the recommendations of various stakeholders, who have

provided through working groups and reports, new elements they hope to

see in SDM that will bolster its success.

The specifics of the governance structure, project proposal modalities,

and overall design were expected to come during the 2016 Conference of the Parties in Marrakesh.

Adaptation provisions

Adaptation

issues garnered more focus in the formation of the Paris Agreement.

Collective, long-term adaptation goals are included in the Agreement,

and countries must report on their adaptation actions, making adaptation

a parallel component of the agreement with mitigation. The adaptation goals focus on enhancing adaptive capacity, increasing resilience, and limiting vulnerability.

Ensuring finance

At the Paris Conference in 2015 where the Agreement was negotiated,

the developed countries reaffirmed the commitment to mobilize $100

billion a year in climate finance by 2020, and agreed to continue

mobilizing finance at the level of $100 billion a year until 2025.

The commitment refers to the pre-existing plan to provide US$100

billion a year in aid to developing countries for actions on climate

change adaptation and mitigation.

Though both mitigation and adaptation require increased climate

financing, adaptation has typically received lower levels of support and

has mobilised less action from the private sector. A 2014 report by the OECD found that just 16 percent of global finance was directed toward climate adaptation in 2014.

The Paris Agreement called for a balance of climate finance between

adaptation and mitigation, and specifically underscoring the need to

increase adaptation support for parties most vulnerable to the effects

of climate change, including Least Developed Countries and Small Island

Developing States. The agreement also reminds parties of the importance

of public grants, because adaptation measures receive less investment

from the public sector. John Kerry, as Secretary of State, announced that the U.S. would double its grant-based adaptation finance by 2020.

Some specific outcomes of the elevated attention to adaptation

financing in Paris include the G7 countries' announcement to provide

US$420 million for Climate Risk Insurance, and the launching of a

Climate Risk and Early Warning Systems (CREWS) Initiative.

In early March 2016, the Obama administration gave a $500 million grant to the "Green Climate Fund" as "the first chunk of a $3 billion commitment made at the Paris climate talks."

So far, the Green Climate Fund has now received over $10 billion in

pledges. Notably, the pledges come from developed nations like France,

the US, and Japan, but also from developing countries such as Mexico,

Indonesia, and Vietnam.

Loss and damage

A new issue that emerged

as a focal point in the Paris negotiations rose from the fact that many

of the worst effects of climate change will be too severe or come too

quickly to be avoided by adaptation measures. The Paris Agreement

specifically acknowledges the need to address loss and damage of this

kind, and aims to find appropriate responses.

It specifies that loss and damage can take various forms—both as

immediate impacts from extreme weather events, and slow onset impacts,

such as the loss of land to sea-level rise for low-lying islands.

The push to address loss and damage as a distinct issue in the

Paris Agreement came from the Alliance of Small Island States and the

Least Developed Countries, whose economies and livelihoods are most

vulnerable to the negative impacts of climate change.

Developed countries, however, worried that classifying the issue as one

separate and beyond adaptation measures would create yet another

climate finance provision, or might imply legal liability for

catastrophic climate events.

In the end, all parties acknowledged the need for "averting,

minimizing, and addressing loss and damage" but notably, any mention of

compensation or liability is excluded.

The agreement also adopts the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss

and Damage, an institution that will attempt to address questions about

how to classify, address, and share responsibility for loss.

Enhanced transparency framework

While

each Party's NDC is not legally binding, the Parties are legally bound

to have their progress tracked by technical expert review to assess

achievement toward the NDC, and to determine ways to strengthen

ambition.

Article 13 of the Paris Agreement articulates an "enhanced transparency

framework for action and support" that establishes harmonized

monitoring, reporting, and verification (MRV) requirements. Thus, both

developed and developing nations must report every two years on their

mitigation efforts, and all parties will be subject to both technical

and peer review.

Flexibility mechanisms

While

the enhanced transparency framework is universal, along with the global

stocktaking to occur every 5 years, the framework is meant to provide

"built-in flexibility" to distinguish between developed and developing

countries' capacities. In conjunction with this, the Paris Agreement has

provisions for an enhanced framework for capacity building.

The agreement recognizes the varying circumstances of some countries,

and specifically notes that the technical expert review for each country

consider that country's specific capacity for reporting.

The agreement also develops a Capacity-Building Initiative for

Transparency to assist developing countries in building the necessary

institutions and processes for complying with the transparency

framework.

There are several ways that flexibility mechanisms can be

incorporated into the enhanced transparency framework. The scope, level

of detail, or frequency of reporting may all be adjusted and tiered

based on a country's capacity. The requirement for in-country technical

reviews could be lifted for some less developed or small island

developing countries. Ways to assess capacity include financial and

human resources in a country necessary for NDC review.

Adoption

The Paris Agreement was opened for signature on 22 April 2016 (Earth Day) at a ceremony in New York.

After several European Union states ratified the agreement in October

2016, there were enough countries that had ratified the agreement that

produce enough of the world's greenhouse gases for the agreement to

enter into force. The agreement went into effect on 4 November 2016.

Negotiations

Within

the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, legal

instruments may be adopted to reach the goals of the convention. For the

period from 2008 to 2012, greenhouse gas reduction measures were agreed

in the Kyoto Protocol in 1997. The scope of the protocol was extended

until 2020 with the Doha Amendment to that protocol in 2012.

During the 2011 United Nations Climate Change Conference, the Durban Platform

(and the Ad Hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced

Action) was established with the aim to negotiate a legal instrument

governing climate change mitigation measures from 2020. The resulting agreement was to be adopted in 2015.

Adoption

Heads of delegations at the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris.

At the conclusion of COP 21 (the 21st meeting of the Conference of

the Parties, which guides the Conference), on 12 December 2015, the

final wording of the Paris Agreement was adopted by consensus by all of

the 195 UNFCCC participating member states and the European Union to reduce emissions as part of the method for reducing greenhouse gas. In the 12-page Agreement,

the members promised to reduce their carbon output "as soon as

possible" and to do their best to keep global warming "to well below

2 °C" [3.6 °F].

Signature and entry into force

Signing by John Kerry in United Nations General Assembly Hall for the United States

The Paris Agreement was open for signature by states and regional

economic integration organizations that are parties to the UNFCCC (the

Convention) from 22 April 2016 to 21 April 2017 at the UN Headquarters

in New York.

The agreement stated that it would enter into force (and thus

become fully effective) only if 55 countries that produce at least 55%

of the world's greenhouse gas emissions (according to a list produced in 2015) ratify, accept, approve or accede to the agreement.

On 1 April 2016, the United States and China, which together represent

almost 40% of global emissions, issued a joint statement confirming that

both countries would sign the Paris Climate Agreement. 175 Parties (174 states and the European Union) signed the agreement on the first date it was open for signature.

On the same day, more than 20 countries issued a statement of their

intent to join as soon as possible with a view to joining in 2016. With

ratification by the European Union, the Agreement obtained enough

parties to enter into effect as of 4 November 2016.

European Union and its member states

Both

the EU and its member states are individually responsible for ratifying

the Paris Agreement. A strong preference was reported that the EU and

its 28 member states deposit their instruments of ratification at the

same time to ensure that neither the EU nor its member states engage

themselves to fulfilling obligations that strictly belong to the other,

and there were fears that disagreement over each individual member

state's share of the EU-wide reduction target, as well as Britain's vote to leave the EU might delay the Paris pact. However, the European Parliament approved ratification of the Paris Agreement on 4 October 2016, and the EU deposited its instruments of ratification on 5 October 2016, along with several individual EU member states.

Implementation

The

process of translating the Paris Agreement into national agendas and

implementation has started. One example is the commitment of the least

developed countries (LDCs). The LDC Renewable Energy and Energy

Efficiency Initiative for Sustainable Development, known as LDC REEEI,

is set to bring sustainable, clean energy to millions of energy-starved

people in LDCs, facilitating improved energy access, the creation of

jobs and contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Per analysis from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

a carbon "budget" based upon total carbon dioxide emissions in the

atmosphere (versus the rate of annual emission) to limit global warming

to 1.5 °C was estimated to be 2.25 trillion tonnes of overall emitted

carbon dioxide from the period since 1870. This number is a notable

increase from the number estimated by the original Paris Climate accord

estimates (of around 2 trillion tonnes total) total carbon emission

limit to meet the 1.5 °C global warming target, a target that would be

met in the year 2020 at current rates of emission. Additionally, the

annual emission of carbon is estimated to be currently at 40 billion

tonnes emitted per year. The revised IPCC budget for this was based upon

CMIP5 climate model. Estimate models using different base-years also provide other slightly adjusted estimates of a carbon "budget".

Parties and signatories

As of February 2019, 194 states and the European Union have signed

the Agreement. 186 states and the EU, representing more than 87% of

global greenhouse gas emissions, have ratified or acceded to the

Agreement, including China, the United States and India, the countries

with three of the four largest greenhouse gas emissions of the UNFCCC members total (about 42% together).

Withdrawal from Agreement

Article 28 of the agreement enables parties to withdraw from the

agreement after sending a withdrawal notification to the depositary, but

notice can be given no earlier than three years after the agreement

goes into force for the country. Withdrawal is effective one year after

the depositary is notified. Alternatively, the Agreement stipulates that

withdrawal from the UNFCCC, under which the Paris Agreement was

adopted, would also withdraw the state from the Paris Agreement. The

conditions for withdrawal from the UNFCCC are the same as for the Paris

Agreement. The agreement does not specify provisions for non-compliance.

On 4 August 2017, the Trump administration

delivered an official notice to the United Nations that the U.S.

intends to withdraw from the Paris Agreement as soon as it is legally

eligible to do so. The formal notice of withdrawal cannot be submitted until the agreement is in force for 3 years for the US, in 2019.

In accordance with Article 28, as the agreement entered into force in

the United States on 4 November 2016, the earliest possible effective

withdrawal date for the United States is 4 November 2020 if notice is

provided on 4 November 2019. If it chooses to withdraw by way of

withdrawing from the UNFCCC, notice could be given immediately (the

UNFCCC entered into force for the US in 1994), and be effective one year

later.

Criticism

Effectiveness

Global CO2 emissions and probabilistic temperature outcomes of Paris

Paris climate accord emission reduction targets and current real-life reductions offered

A pair of studies in Nature

have said that, as of 2017, none of the major industrialized nations

were implementing the policies they had envisioned and have not met

their pledged emission reduction targets, and even if they had, the sum of all member pledges (as of 2016) would not keep global temperature rise "well below 2 °C". According to UNEP

the emission cut targets in November 2016 will result in temperature

rise by 3 °C above pre-industrial levels, far above the 2 °C of the

Paris climate agreement.

In addition, an MIT News article written on 22 April 2016

discussed recent MIT studies on the true impact that the Paris Agreement

had on global temperature increase. Using their Integrated Global

System Modeling (IGSM) to predict temperature increase results in 2100,

they used a wide range of scenarios that included no effort towards

climate change past 2030, and full extension of the Paris Agreement past

2030. They concluded that the Paris Agreement would cause temperature

decrease by about 0.6 to 1.1 degrees Celsius compared to a

no-effort-scenario, with only a 0.1 °C change in 2050 for all scenarios.

They concluded that, although beneficial, there was strong evidence

that the goal provided by the Paris Agreement could not be met in the

future; under all scenarios, warming would be at least 3.0 °C by 2100.

How well each individual country is on track to achieving its Paris agreement commitments can be continuously followed on-line.

A 2018 published study points at a threshold at which

temperatures could rise to 4 or 5 degrees compared to the pre-industrial

levels, through self-reinforcing feedbacks

in the climate system, suggesting this threshold is below the 2-degree

temperature target, agreed upon by the Paris climate deal. Study author

Katherine Richardson stresses, "We note that the Earth has never in its

history had a quasi-stable state that is around 2 °C warmer than the

pre-industrial and suggest that there is substantial risk that the

system, itself, will 'want' to continue warming because of all of these

other processes – even if we stop emissions. This implies not only

reducing emissions but much more."

At the same time, another 2018 published study notes that even at

a 1.5 °C level of warming, important increases in the occurrence of

high river flows would be expected in India, South and Southeast Asia.

Yet, the same study points out that under a 2.0 °C of warming various

areas in South America, central Africa, western Europe, and the

Mississippi area in the United States would see more high flows; thus

increasing flood risks.

Lack of binding enforcement mechanism

Although the agreement was lauded by many, including French President François Hollande and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, criticism has also surfaced. For example, James Hansen,

a former NASA scientist and a climate change expert, voiced anger that

most of the agreement consists of "promises" or aims and not firm

commitments. He called the Paris talks a fraud with 'no action, just promises' and feels that only an across the board tax on CO

2 emissions, something not part of the Paris Agreement, would force CO

2 emissions down fast enough to avoid the worst effects of global warming.

2 emissions, something not part of the Paris Agreement, would force CO

2 emissions down fast enough to avoid the worst effects of global warming.

Institutional asset owners associations and think-tanks have also

observed that the stated objectives of the Paris Agreement are

implicitly "predicated upon an assumption – that member states of the

United Nations, including high polluters such as China, the US, India,

Russia, Japan, Germany, South Korea, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Canada,

Indonesia and Mexico, which generate more than half the world's

greenhouse gas emissions, will somehow drive down their carbon pollution

voluntarily and assiduously without any binding enforcement mechanism

to measure and control CO

2 emissions at any level from factory to state, and without any specific penalty gradation or fiscal pressure (for example a carbon tax) to discourage bad behaviour." Emissions taxes (such as a carbon tax) can be integrated into the country's NDC however.

2 emissions at any level from factory to state, and without any specific penalty gradation or fiscal pressure (for example a carbon tax) to discourage bad behaviour." Emissions taxes (such as a carbon tax) can be integrated into the country's NDC however.