| Prostate | |

|---|---|

Male Anatomy

| |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Endodermic evaginations of the urethra |

| Artery | Internal pudendal artery, inferior vesical artery, and middle rectal artery |

| Vein | Prostatic venous plexus, pudendal plexus, vesical plexus, internal iliac vein |

| Nerve | Inferior hypogastric plexus |

| Lymph | internal iliac lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Prostata |

| MeSH | D011467 |

| TA | A09.3.08.001 |

| FMA | 9600 |

The prostate is an exocrine gland of the male reproductive system in most mammals. It differs considerably among species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. The word prostate comes from Ancient Greek προστάτης, prostátēs, literally "one who stands before", "protector", "guardian".

Anatomically, the prostate can be subdivided in two ways: by zone or by lobe. It does not have a capsule; rather an integral fibromuscular band surrounds it. It is sheathed in the muscles of the pelvic floor, which contract during the ejaculatory process. The prostate also contains some smooth muscles that also help expel semen during ejaculation.

The function of the prostate is to secrete a fluid which contributes to the volume of the semen. This prostatic fluid is slightly alkaline, milky or white in appearance, and in humans usually constitutes roughly 30% of the volume of semen, the other 70% being spermatozoa and seminal vesicle fluid. The alkalinity of semen helps neutralize the acidity of the vaginal tract, prolonging the lifespan of sperm.

The prostatic fluid is expelled in the first part of ejaculate, together with most of the sperm. In comparison with the few spermatozoa expelled together with mainly seminal vesicular fluid, those in prostatic fluid have better motility, longer survival, and better protection of genetic material.

Disorders of the prostate include enlargement, inflammation, infection, and cancer.

Structure

Prostate with seminal vesicles and seminal ducts, viewed from in front and above.

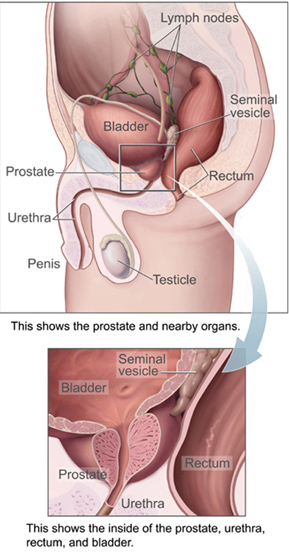

The prostate is a gland found in males. In adults, it is about the size of a walnut. The prostate is located in the pelvis. Within it sits the urethra coming from the bladder which is called the prostatic urethra and which merges with the two ejaculatory ducts.

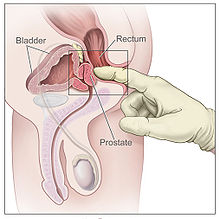

The mean weight of the normal prostate in adult males is about 11 grams, usually ranging between 7 and 16 grams. The volume of the prostate can be estimated by the formula 0.52 × length × width × height. A volume of over 30 cm3 is regarded as prostatomegaly (enlarged prostate). A study stated that prostate volume among patients with negative biopsy is related significantly with weight and height (body mass index), so it is necessary to control for weight. The prostate surrounds the urethra just below the urinary bladder and can be felt during a rectal exam.

It does not have a capsule; rather an integral fibromuscular band surrounds it. It is sheathed in the muscles of the pelvic floor, which contract during the ejaculatory process.

Subdivisions

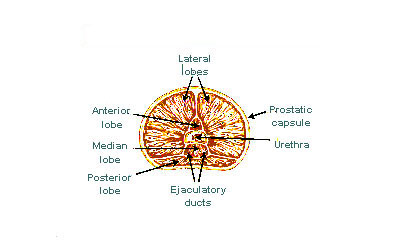

One can sub-divide the prostate in two ways: by zone or by lobe. Because of the variation in descriptions and definitions of lobes, zones form the predominant way the prostate is described.

Lobes

The "lobe" classification is more often used in anatomy. The prostate is incompletely divided into five lobes:

| Anterior lobe (or isthmus) | roughly corresponds to part of transitional zone |

| Posterior lobe | roughly corresponds to peripheral zone |

| Right & left Lateral lobes | span all zones |

| Median lobe (or middle lobe) | roughly corresponds to part of central zone |

Zones

The prostate has been described as consisting of three or four zones. This "zone" classification is more often used in pathology. The prostate gland has four distinct glandular regions, two of which arise from different segments of the prostatic urethra:

| Name | Fraction of adult gland | Description |

| Peripheral zone (PZ) | 70% | The sub-capsular portion of the posterior aspect of the prostate gland that surrounds the distal urethra. ~70–80% of prostatic cancers originate from this portion of the gland. |

| Central zone (CZ) | 20% | This zone surrounds the ejaculatory ducts. The central zone accounts for roughly 2.5% of prostate cancers; these cancers tend to be more aggressive and more likely to invade the seminal vesicles. |

| Transition zone (TZ) | 5% | The transition zone surrounds the proximal urethra. ~10–20% of prostate cancers originate in this zone. It is the region of the prostate gland that grows throughout life and causes the disease of benign prostatic enlargement. |

| Anterior fibro-muscular zone (or stroma) | N/A | This area, not always considered a zone, is usually devoid of glandular components and composed only, as its name suggests, of muscle and fibrous tissue. |

Blood and lymphatic vessels

The veins of the prostate form a network (Latin: plexus) primarily around its front and outer surface. This network also receives blood from the deep dorsal vein of the penis, and is connected via branches (Latin: rami) to the vesical plexus and internal pudendal veins. Veins drain into the vesical and then internal iliac veins.

The lymphatic drainage of the prostate depends on the positioning

of the area. Vessels surrounding the vas deferens, some of the vessels

in the seminal vesicle, and a vessel from the posterior surface of the

prostate drain into the external iliac lymph nodes. Some of the seminal vesicle vessels, prostatic vessels, and vessels from the anterior prostate drain into internal iliac lymph nodes. Vessels of the prostate itself also drain into the sacral and obdurator lymph nodes.

- Some named lymph glands of the pelvis.

Microanatomy

Micrograph of benign prostatic glands with corpora amylacea. H&E stain

The tissue of the prostate consists of glands and stroma. Tall column-shaped cells form the lining (epithelium) of the glands. These lie in either one layer or are pseudostratified. The epithelium is highly variable and areas of low cuboidal or squamous epithelium are also present, with transitional epithelium in the distal regions of the longer ducts.

The glands are found as numerous follicles, which in turn drain into

long canals and subsequently 12 - 20 main ducts, which in turn drain

into the urethra as it passes through the prostate. There are also a small amount of basal cells, which sit next to the basement membranes of glands, and act as stem cells.

The stroma of the prostate is made up of fibrous tissue and smooth muscle. The fibrous tissue separates the gland into lobules.

It also sits between the glands and is composed of randomly orientated

smooth-muscle bundles that are continuous with the bladder.

Over time, thickened secretions called corpora amylacea accumulate in the gland.

Three histological types of cells are present in the prostate

gland: glandular cells, myoepithelial cells, and subepithelial

interstitial cells.

Gene and protein expression

About 20,000 protein coding genes are expressed in human cells and

almost 75% of these genes are expressed in the normal prostate. About 150 of these genes are more specifically expressed in the prostate with about 20 genes being highly prostate specific.

The corresponding specific proteins are expressed in the glandular and

secretory cells of the prostatic gland and have functions that are

important for the characteristics of semen. Some of the prostate specific proteins are enzymes, such as the prostate specific antigen (PSA), and the ACPP protein.

Development

The prostatic part of the urethra develops from the middle, pelvic, part of the urogenital sinus, of endodermal origin.

Around the end of the third month of embryonic life, outgrowths arise

from the prostatic part of the urethra and grow into the surrounding mesenchyme. The cells lining this part of the urethra differentiate into the glandular epithelium of the prostate. The associated mesenchyme differentiates into the dense stroma and the smooth muscle of the prostate.

Condensation of mesenchyme, urethra, and Wolffian ducts

gives rise to the adult prostate gland, a composite organ made up of

several tightly fused glandular and non-glandular components.

To function properly, the prostate needs male hormones (androgens), which are responsible for male sex characteristics. The main male hormone is testosterone, which is produced mainly by the testicles. It is dihydrotestosterone (DHT), a metabolite of testosterone, that predominantly regulates the prostate.

The prostate gland enlarges over time, until the fourth decade of life.

Function

Male sexual response

During male seminal emission, sperm is transmitted from the vas deferens into the male urethra via the ejaculatory ducts, which lie within the prostate gland. Ejaculation is the expulsion of semen from the urethra.

Semen is moved into the urethra following contractions of the smooth

muscle of the vas deferens and seminal vesicles, following stimulation,

primarily of the glans penis. Stimulation sends nerve signals via the internal pudendal nerves to the upper lumbar spine; the nerve signals causing contraction act via the hypogastric nerves. After traveling into the urethra, the seminal fluid is ejaculated out by contraction of the bulbocavernosus muscle.

It is possible for some men to achieve orgasm solely through stimulation of the prostate gland, such as prostate massage or anal intercourse.

Secretions

In human prostatic secretions, the protein content is less than 1%, and the contents are slightly acidic. Contents include proteolytic enzymes, prostatic acid phosphatase, fibrinolysin, and prostate-specific antigen. The secretions also contain zinc with a concentration 500–1,000 times the concentration in blood.

Clinical significance

Inflammation

A digital rectal examinations may be performed to investigate how large a prostate is, or if a prostate is tender (which may indicate inflammation).

Micrograph showing an inflamed prostate gland, the histologic correlate of prostatitis. A normal non-inflamed prostatic gland is seen on the left of the image. H&E stain

Micrograph showing normal prostatic glands and glands of prostate cancer (prostatic adenocarcinoma) – right upper aspect of image. HPS stain. Prostate biopsy

Prostatitis is inflammation

of the prostate gland. It can be caused by infection with bacteria, or

other noninfective causes. Inflammation of the prostate can cause painful urination or ejaculation, groin pain, difficulty passing urine, or constitutional symptoms. The prostate is enlarged (prostatomegaly) and tender on digital rectal examination. A culprit bacteria may grow in a urine culture.

Acute prostatitis and chronic bacterial prostatitis are treated with antibiotics. Chronic non-bacterial prostatitis, or male chronic pelvic pain syndrome is treated by a large variety of modalities including alpha blockers, nonsteroidal antiinflammatories and amitriptyline. Other treatments may include physical therapy, psychotherapy, antihistamines, anxiolytics, nerve modulators, phytotherapy, surgery, and more. More recently, a combination of trigger point and psychological therapy has proved effective for category III prostatitis as well.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

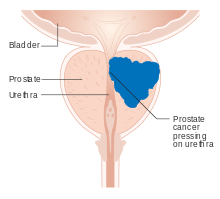

Benign prostatic hyperplasia refers to a non-malignant enlargement (hyperplasia) of the prostate that is very common in older men.

It is often identified when the prostate has enlarged to the point

where urination becomes difficult. Symptoms include needing to urinate

often (frequency), or taking a while to get started (hesitancy). If the

prostate grows too large, it may constrict the urethra and impede the

flow of urine, making urination difficult and painful and, in extreme

cases, completely impossible, causing urinary retention. Over time, chronic retention may cause the bladder to become larger and cause a backflow of urine into the kidneys (hydronephrosis).

BPH can be treated with medication, a minimally invasive procedure or, in extreme cases, surgery that removes the prostate. In general, treatment often begins with a alpha antagonist medication such as tamsulosin, which reduces the tone of the smooth muscle found in the ureter that passes through the prostate, making it easier for urine to pass through. For people with persistent symptoms, procedures may be considered. The surgery most often used in such cases is called transurethral resection of the prostate,

in which an instrument is inserted through the urethra to remove

prostate tissue that is pressing against the upper part of the urethra and restricting the flow of urine. This results in the removal of mostly transitional zone tissue in a patient with BPH. Minimally invasive procedures include transurethral needle ablation of the prostate (TUNA) and transurethral microwave thermotherapy (TUMT). These outpatient procedures may be followed by the insertion of a temporary prostatic stent, to allow normal voluntary urination, without exacerbating irritative symptoms. In some cases, "obesity management may be an effective method to reduce prostate volume."

Cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common cancers affecting older men in the UK, US and Northern Europe and a significant cause of death for elderly men in these countries.

Often, a person does not have symptoms; when they do occur, symptoms

may include frequency, urgency, hesitation and other symptoms associated

with BPH. Uncommonly, such cancers may cause weight loss, urinary

retention, or other symptoms due to lesions outside of the prostate,

such as back pain.

A digital rectal examination and the measurement of a prostate specific antigen

(PSA) level are usually the first investigations done to check for

prostate cancer. PSA values are difficult to interpret, because a high

value might be present in a person without cancer, and a low value can

be present in someone with cancer. The next form of testing is often the taking of a biopsy to assess for tumour activity and invasiveness. Because of the significant risk of overdiagnosis with widespread screening in the general population, prostate cancer screening is controversial. If a tumour is confirmed, medical imaging such as an MRI or bone scan may be done to check for the presence of tumour metastases in other parts of the body.

Prostate cancer that is only present in the prostate is often treated with either surgical removal of the prostate or with radiotherapy or by the insertion of small radioactive particles (brachytherapy)

Cancer that has spread to other parts of the body is usually treated

with hormone therapy, to deprive a tumour of sex hormones (androgens)

that stimulate proliferation. This is often done through the use of GnRH analogues or agents that block the receptors that androgens act at, such as bicalutamide; occasionally, surgical removal of the testes may be done instead. Cancer that does not respond to hormonal treatment, or that progresses after treatment, might be treated with chemotherapy such as docetaxel. Radiotherapy may also be used to help with pain associated with bony lesions.

Sometimes, the decision may be made not to treat prostate cancer.

If a cancer is small and localised, the decision may be made to monitor

for cancer activity at intervals ("Active surveillance") and defer

treatment. If a person, because of frailty or other medical conditions or reasons, has a life expectancy less than ten years, then the impacts of treatment may outweigh any perceived benefits.

History

John E.

McNeal first proposed the idea of "zones" in 1968. McNeal found that

the relatively homogeneous cut surface of an adult prostate in no way

resembled "lobes" and thus led to the description of "zones".

Other animals

In mammals

The prostate is found as a male accessory gland in all placental mammals excepting edentates, martens, badgers and otters. The prostate glands of male marsupials are disseminate and proportionally larger than those of placental mammals. In some marsupial species, the size of the prostate gland changes seasonally. The structure of the prostate varies, ranging from tubuloalveolar (as in humans) to branched tubular.

The gland is particularly well developed in dogs, foxes and boars,

though in other mammals, such as bulls, it can be small and

inconspicuous.

Dogs can produce in one hour as much prostatic fluid as a human can in a

day. They excrete this fluid along with their urine to mark their territory. In many rodents and bats, the prostatic fluid contains a coagulant. This mixes with and coagulates semen during copulation to form a mating plug that temporarily prevents further copulation. In cetaceans the prostate is composed of diffuse urethral glands and is surrounded by a very powerful compressor muscle.

Prostatic secretions vary among species. They are generally composed of simple sugars and are often slightly alkaline.

The prostate gland originates with tissues in the urethral wall. This means the urethra,

a compressible tube used for urination, runs through the middle of the

prostate. This leads to an evolutionary design fault for some mammals,

including human males. The prostate is prone to infection and

enlargement later in life, constricting the urethra so urinating becomes

slow and painful.

Monotremes and marsupial moles lack prostates, instead having simpler cloacal glands that carry their function.

In invertebrates

A prostate gland also occurs in some invertebrate species, such as gastropods.

Skene's gland

Skene's gland is found in both female humans and rodents. Historically it was thought to be a vestigial organ, but recently it has been discovered that it produces the same protein markers, PSA and PAB, as the male prostate. This means Skene's gland functions as a female prostate, a histologic homolog to the male prostate gland.