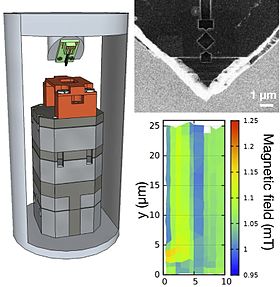

Left:

Schematic of a scanning SQUID microscope in a helium-4 refrigerator.

Green holder for the SQUID probe is attached to a quartz tuning fork.

Bottom part is a piezoelectric sample stage. Right: electron micrograph

of a SQUID probe and a test image of Nb/Au strips recorded with it.

Scanning SQUID microscopy is a technique where a superconducting quantum interference device

(SQUID) is used to image surface magnetic field strength with

micrometre scale resolution. A tiny SQUID is mounted onto a tip which is

then rastered near the surface of the sample to be measured. As the

SQUID is the most sensitive detector of magnetic fields available and

can be constructed at submicrometre widths via lithography, the scanning

SQUID microscope allows magnetic fields to be measured with

unparalleled resolution and sensitivity. The first scanning SQUID

microscope was built in 1992 by Black et al. Since then the technique has been used to confirm unconventional superconductity in several high-temperature superconductors including YBCO and BSCCO compounds.

Operating principles

Diagram of a DC SQUID. The current enters and splits into the two paths, each with currents and . The thin barriers on each path are Josephson junctions, which together separate the two superconducting regions. represents the magnetic flux entering the inside of the DC SQUID loop.

The scanning SQUID microscope is based upon the thin-film DC SQUID. A DC SQUID consists of superconducting electrodes in a ring pattern connected by two weak-link Josephson junctions (see figure). Above the critical current of the Josephson junctions, the idealized difference in voltage between the electrodes is given by

where R is the resistance between the electrodes, I is the current, I0 is the maximum supercurrent, Ic is the critical current of the Josephson junctions, Φ is the total magnetic flux through the ring, and Φ0 is the magnetic flux quantum.

Hence, a DC SQUID can be used as a flux-to-voltage transducer. However, as noted by the figure, the voltage across the electrodes oscillates sinusoidally

with respect to the amount of magnetic flux passing through the device.

As a result, alone a SQUID can only be used to measure the change in

magnetic field from some known value, unless the magnetic field or

device size is very small such that Φ < Φ0. To use the DC

SQUID to measure standard magnetic fields, one must either count the

number of oscillations in the voltage as the field is changed, which is

very difficult in practice, or use a separate DC bias magnetic field

parallel to the device to maintain a constant voltage and consequently

constant magnetic flux through the loop. The strength of the field being

measured will then be equal to the strength of the bias magnetic field

passing through the SQUID.

Although it is possible to read the DC voltage between the two

terminals of the SQUID directly, because noise tends to be a problem in

DC measurements, an alternating current

technique is used. In addition to the DC bias magnetic field, an AC

magnetic field of constant amplitude, with field strength generating

Φ << Φ0, is also emitted in the bias coil. This AC

field produces an AC voltage with amplitude proportional to the DC

component in the SQUID. The advantage of this technique is that the

frequency of the voltage signal can be chosen to be far away from that

of any potential noise sources. By using a lock-in amplifier the device can read only the frequency corresponding to the magnetic field, ignoring many other sources of noise.

Instrumentation

As

the SQUID material must be superconducting, measurements must be

performed at low temperatures. Typically, experiments are carried out

below liquid helium temperature (4.2 K) in a helium-3 refrigerator or dilution refrigerator. However, advances in high-temperature superconductor thin-film growth have allowed relatively inexpensive liquid nitrogen cooling to instead be used. It is even possible to measure room-temperature samples by only cooling a high Tc

squid and maintaining thermal separation with the sample. In either

case, due to the extreme sensitivity of the SQUID probe to stray

magnetic fields, in general some form of magnetic shielding is used. Most common is a shield made of mu-metal, possibly in combination with a superconducting "can" (all superconductors repel magnetic fields via the Meissner effect).

The actual SQUID probe is generally made via thin-film deposition with the SQUID area outlined via lithography. A wide variety of superconducting materials can be used, but the two most common are Niobium, due to its relatively good resistance to damage from thermal cycling, and YBCO, for its high Tc > 77 K and relative ease of deposition compared to other high Tc superconductors. In either case, a superconductor with critical temperature higher than that of the operating temperature

should be chosen. The SQUID itself can be used as the pickup coil for

measuring the magnetic field, in which case the resolution of the device

is proportional to the size of the SQUID. However, currents in or near

the SQUID generate magnetic fields which are then registered in the coil

and can be a source of noise. To reduce this effect it is also possible

to make the size of the SQUID itself very small, but attach the device

to a larger external superconducting loop located far from the SQUID.

The flux through the loop will then be detected and measured, inducing a

voltage in the SQUID.

The resolution and sensitivity of the device are both

proportional to the size of the SQUID. A smaller device will have

greater resolution but less sensitivity. The change in voltage induced

is proportional to the inductance

of the device, and limitations in the control of the bias magnetic

field as well as electronics issues prevent a perfectly constant voltage

from being maintained at all times. However, in practice, the

sensitivity in most scanning SQUID microscopes is sufficient for almost

any SQUID size for many applications, and therefore the tendency is to

make the SQUID as small as possible to enhance resolution. Via e-beam lithography techniques it is possible to fabricate devices with total area of 1–10 μm2, although devices in the tens to hundreds of square micrometres are more common.

The SQUID itself is mounted onto a cantilever

and operated either in direct contact with or just above the sample

surface. The position of the SQUID is usually controlled by some form of

electric stepping motor.

Depending on the particular application, different levels of precision

may be required in the height of the apparatus. Operating at lower-tip

sample distances increases the sensitivity and resolution of the device,

but requires more advanced mechanisms in controlling the height of the

probe. In addition such devices require extensive vibration dampening if precise height control is to be maintained.

Operation

Operation of a scanning SQUID microscope consists of simply cooling down the probe and sample, and rastering

the tip across the area where measurements are desired. As the change

in voltage corresponding to the measured magnetic field is quite rapid,

the strength of the bias magnetic field is typically controlled by

feedback electronics. This field strength is then recorded by a computer

system that also keeps track of the position of the probe. An optical

camera can also be used to track the position of the SQUID with respect

to the sample.

Applications

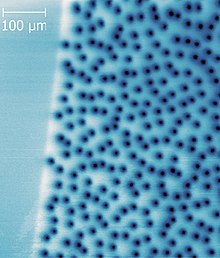

Quantum vortices in YBCO imaged by the scanning SQUID microscopy

The scanning SQUID microscope was originally developed for an

experiment to test the pairing symmetry of the high-temperature cuprate

superconductor YBCO. Standard superconductors are isotropic with respect to their superconducting properties, that is, for any direction of electron momentum k in the superconductor, the magnitude of the order parameter and consequently the superconducting energy gap will be the same. However, in the high-temperature cuprate superconductors, the order parameter instead follows the equation

Δ(k) = Δ0(cos(kxa)-cos(kya)),

meaning that when crossing over any of the [110] directions in momentum

space one will observe a sign change in the order parameter. The form

of this function is equal to that of the l = 2 spherical harmonic

function, giving it the name d-wave superconductivity. As the

superconducting electrons are described by a single coherent

wavefunction, proportional to exp(-iφ), where φ is known as the phase of the wavefunction, this property can be also interpreted as a phase shift of π under a 90 degree rotation.

This property was exploited by Tsuei et al. by manufacturing a series of YBCO ring Josephson junctions which crossed Bragg planes

of a single YBCO crystal (figure). In a Josephson junction ring the

superconducting electrons form a coherent wave function, just as in a

superconductor. As the wavefunction must have only one value at each

point, the overall phase factor obtained after traversing the entire

Josephson circuit must be an integer multiple of 2π, as otherwise, one

would obtain a different value of the probability density depending on

the number of times one traversed the ring.

In YBCO, upon crossing the [110] planes in momentum (and real)

space, the wavefunction will undergo a phase shift of π. Hence if one

forms a Josephson ring device where this plane is crossed (2n+1), number of times, a phase difference of (2n+1)π will be observed between the two junctions. For 2n, or even number of crossings, as in B, C, and D, a phase difference of (2n)π

will be observed. Compared to the case of standard s-wave junctions,

where no phase shift is observed, no anomalous effects were expected in

the B, C, and D cases, as the single valued property is conserved, but

for device A, the system must do something to for the φ=2nπ

condition to be maintained. In the same property behind the scanning

SQUID microscope, the phase of the wavefunction is also altered by the

amount of magnetic flux passing through the junction, following the

relationship Δφ=π(Φ0). As was predicted by Sigrist and Rice, the phase condition can then be maintained in the junction by a spontaneous flux in the junction of value Φ0/2.

Tsuei et al. used a scanning SQUID microscope to measure

the local magnetic field at each of the devices in the figure, and

observed a field in ring A approximately equal in magnitude Φ0/2A, where A

was the area of the ring. The device observed zero field at B, C, and

D. The results provided one of the earliest and most direct experimental

confirmations of d-wave pairing in YBCO.