From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Religious views

As late as 1952, the editorial staff of the Syntopicon found in their compilation of the Great Books of the Western World,

that "The philosophical issue concerning immortality cannot be

separated from issues concerning the existence and nature of man's

soul." Thus, the vast majority of speculation regarding immortality before the 21st century was regarding the nature of the afterlife.

Ancient Greek religion

Immortality in ancient Greek religion originally always included an eternal union of body and soul as can be seen in Homer, Hesiod,

and various other ancient texts. The soul was considered to have an

eternal existence in Hades, but without the body the soul was considered

dead. Although almost everybody had nothing to look forward to but an

eternal existence as a disembodied dead soul, a number of men and women

were considered to have gained physical immortality and been brought to

live forever in either Elysium, the Islands of the Blessed, heaven, the ocean or literally right under the ground. Among these were Amphiaraus, Ganymede, Ino, Iphigenia, Menelaus, Peleus,

and a great part of those who fought in the Trojan and Theban wars.

Some were considered to have died and been resurrected before they

achieved physical immortality. Asclepius was killed by Zeus only to be resurrected and transformed into a major deity. In some versions of the Trojan War myth, Achilles,

after being killed, was snatched from his funeral pyre by his divine

mother Thetis, resurrected, and brought to an immortal existence in

either Leuce, the Elysian plains, or the Islands of the Blessed. Memnon, who was killed by Achilles, seems to have received a similar fate. Alcmene, Castor, Heracles, and Melicertes were also among the figures sometimes considered to have been resurrected to physical immortality. According to Herodotus' Histories, the 7th century BC sage Aristeas of Proconnesus

was first found dead, after which his body disappeared from a locked

room. Later he was found not only to have been resurrected but to have

gained immortality.

The philosophical idea of an immortal soul was a belief first appearing with either Pherecydes or the Orphics, and most importantly advocated by Plato

and his followers. This, however, never became the general norm in

Hellenistic thought. As may be witnessed even into the Christian era,

not least by the complaints of various philosophers over popular

beliefs, many or perhaps most traditional Greeks maintained the

conviction that certain individuals were resurrected from the dead and

made physically immortal and that others could only look forward to an

existence as disembodied and dead, though everlasting, souls. The

parallel between these traditional beliefs and the later resurrection of

Jesus was not lost on the early Christians, as Justin Martyr

argued: "when we say ... Jesus Christ, our teacher, was crucified and

died, and rose again, and ascended into heaven, we propose nothing

different from what you believe regarding those whom you consider sons

of Zeus." (1 Apol. 21).

Buddhism

According to one Tibetan Buddhist teaching, Dzogchen, individuals can transform the physical body into an immortal body of light called the rainbow body.

Christianity

Adam and Eve condemned to mortality. Hans Holbein the Younger, Danse Macabre, 16th century

Christian theology holds that Adam and Eve lost physical immortality for themselves and all their descendants in the Fall of man, although this initial "imperishability of the bodily frame of man" was "a preternatural condition".

Christians who profess the Nicene Creed believe that every dead person (whether they believed in Christ or not) will be resurrected from the dead at the Second Coming, and this belief is known as Universal resurrection.

N.T. Wright, a theologian and former Bishop of Durham, has said many people forget the physical aspect of what Jesus promised. He told Time: "Jesus' resurrection marks the beginning of a restoration that he will complete upon his return. Part of this will be the resurrection of all the dead, who will 'awake', be embodied and participate in the renewal. Wright says John Polkinghorne,

a physicist and a priest, has put it this way: 'God will download our

software onto his hardware until the time he gives us new hardware to

run the software again for ourselves.' That gets to two things nicely:

that the period after death (the Intermediate state)

is a period when we are in God's presence but not active in our own

bodies, and also that the more important transformation will be when we

are again embodied and administering Christ's kingdom." This kingdom will consist of Heaven and Earth "joined together in a new creation", he said.

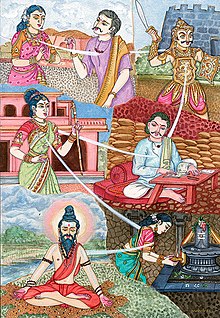

Hinduism

Representation of a soul undergoing punarjanma. Illustration from Hinduism Today, 2004

Hindus believe in an immortal soul which is reincarnated after death. According to Hinduism, people repeat a process of life, death, and rebirth in a cycle called samsara. If they live their life well, their karma

improves and their station in the next life will be higher, and

conversely lower if they live their life poorly. After many life times

of perfecting its karma, the soul is freed from the cycle and lives in

perpetual bliss. There is no place of eternal torment in Hinduism,

although if a soul consistently lives very evil lives, it could work its

way down to the very bottom of the cycle.

There are explicit renderings in the Upanishads

alluding to a physically immortal state brought about by purification,

and sublimation of the 5 elements that make up the body. For example, in

the Shvetashvatara Upanishad

(Chapter 2, Verse 12), it is stated "When earth, water, fire, air and

sky arise, that is to say, when the five attributes of the elements,

mentioned in the books on yoga, become manifest then the yogi's body

becomes purified by the fire of yoga and he is free from illness, old

age and death."

Another view of immortality is traced to the Vedic tradition by the interpretation of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi:

That man indeed whom these (contacts)

do not disturb, who is even-minded in

pleasure and pain, steadfast, he is fit

for immortality, O best of men.

To Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the verse means, "Once a man has become

established in the understanding of the permanent reality of life, his

mind rises above the influence of pleasure and pain. Such an unshakable

man passes beyond the influence of death and in the permanent phase of

life: he attains eternal life ... A man established in the understanding

of the unlimited abundance of absolute existence is naturally free from

existence of the relative order. This is what gives him the status of

immortal life."

An Indian Tamil saint known as Vallalar claimed to have achieved immortality before disappearing forever from a locked room in 1874.

Judaism

The traditional concept of an immaterial and immortal soul distinct from the body was not found in Judaism before the Babylonian Exile, but developed as a result of interaction with Persian and Hellenistic philosophies. Accordingly, the Hebrew word nephesh, although translated as "soul" in some older English Bibles, actually has a meaning closer to "living being". Nephesh was rendered in the Septuagint as ψυχή (psūchê), the Greek word for soul.

The only Hebrew word traditionally translated "soul" (nephesh) in English language Bibles refers to a living, breathing conscious body, rather than to an immortal soul. In the New Testament, the Greek word traditionally translated "soul" (ψυχή) has substantially the same meaning as the Hebrew, without reference to an immortal soul. ‘Soul’ may refer to the whole person, the self: ‘three thousand souls’ were converted in Acts 2:41 (see Acts 3:23).

The Hebrew Bible speaks about Sheol (שאול), originally a synonym of the grave-the repository of the dead or the cessation of existence until the resurrection of the dead. This doctrine of resurrection is mentioned explicitly only in Daniel 12:1–4 although it may be implied in several other texts. New theories arose concerning Sheol during the intertestamental period.

The views about immortality in Judaism is perhaps best exemplified by the various references to this in Second Temple Period. The concept of resurrection of the physical body is found in 2 Maccabees, according to which it will happen through recreation of the flesh. Resurrection of the dead also appears in detail in the extra-canonical books of Enoch, and in Apocalypse of Baruch. According to the British scholar in ancient Judaism Philip R. Davies, there is “little or no clear reference … either to immortality or to resurrection from the dead” in the Dead Sea scrolls texts. Both Josephus and the New Testament record that the Sadducees did not believe in an afterlife, but the sources vary on the beliefs of the Pharisees.

The New Testament claims that the Pharisees believed in the

resurrection, but does not specify whether this included the flesh or

not. According to Josephus, who himself was a Pharisee, the Pharisees held that only the soul was immortal and the souls of good people will be reincarnated and “pass into other bodies,” while “the souls of the wicked will suffer eternal punishment.” Jubilees seems to refer to the resurrection of the soul only, or to a more general idea of an immortal soul.

Rabbinic Judaism claims that the righteous dead will be resurrected in the Messianic Age with the coming of the messiah.

They will then be granted immortality in a perfect world. The wicked

dead, on the other hand, will not be resurrected at all. This is not the

only Jewish belief about the afterlife. The Tanakh is not specific about the afterlife, so there are wide differences in views and explanations among believers.

Taoism

It is repeatedly stated in the Lüshi Chunqiu that death is unavoidable. Henri Maspero noted that many scholarly works frame Taoism as a school of thought focused on the quest for immortality. Isabelle Robinet asserts that Taoism is better understood as a way of life than as a religion, and that its adherents do not approach or view Taoism the way non-Taoist historians have done.

In the Tractate of Actions and their Retributions, a traditional

teaching, spiritual immortality can be rewarded to people who do a

certain amount of good deeds and live a simple, pure life. A list of

good deeds and sins are tallied to determine whether or not a mortal is

worthy. Spiritual immortality in this definition allows the soul to

leave the earthly realms of afterlife and go to pure realms in the

Taoist cosmology.

Zoroastrianism

Zoroastrians

believe that on the fourth day after death, the human soul leaves the

body and the body remains as an empty shell. Souls would go to either

heaven or hell; these concepts of the afterlife in Zoroastrianism may

have influenced Abrahamic religions. The Persian word for "immortal" is

associated with the month "Amurdad", meaning "deathless" in Persian, in

the Iranian calendar (near the end of July). The month of Amurdad or Ameretat

is celebrated in Persian culture as ancient Persians believed the

"Angel of Immortality" won over the "Angel of Death" in this month.

Philosophical arguments for the immortality of the soul

Alcmaeon of Croton

Alcmaeon of Croton

argued that the soul is continuously and ceaselessly in motion. The

exact form of his argument is unclear, but it appears to have influenced

Plato, Aristotle, and other later writers.

Plato

- The Cyclical Argument, or Opposites Argument explains that Forms are eternal and unchanging, and as the soul always brings life, then it must not die, and is necessarily "imperishable". As the body is mortal and is subject to physical death, the soul must be its indestructible opposite. Plato then suggests the analogy of fire and cold. If the form of cold is imperishable, and fire, its opposite, was within close proximity, it would have to withdraw intact as does the soul during death. This could be likened to the idea of the opposite charges of magnets.

- The Theory of Recollection explains that we possess some non-empirical knowledge (e.g. The Form of Equality) at birth, implying the soul existed before birth to carry that knowledge. Another account of the theory is found in Plato's Meno, although in that case Socrates implies anamnesis (previous knowledge of everything) whereas he is not so bold in Phaedo.

- The Affinity Argument, explains that invisible, immortal, and incorporeal things are different from visible, mortal, and corporeal things. Our soul is of the former, while our body is of the latter, so when our bodies die and decay, our soul will continue to live.

- The Argument from Form of Life,

or The Final Argument explains that the Forms, incorporeal and static

entities, are the cause of all things in the world, and all things

participate in Forms. For example, beautiful things participate in the

Form of Beauty; the number four participates in the Form of the Even,

etc. The soul, by its very nature, participates in the Form of Life,

which means the soul can never die.

Plotinus

Plotinus

offers a version of the argument that Kant calls "The Achilles of

Rationalist Psychology". Plotinus first argues that the soul is simple,

then notes that a simple being cannot decompose. Many subsequent

philosophers have argued both that the soul is simple and that it must

be immortal. The tradition arguably culminates with Moses Mendelssohn's Phaedon.

Metochites

Theodore Metochites

argues that part of the soul's nature is to move itself, but that a

given movement will cease only if what causes the movement is separated

from the thing moved – an impossibility if they are one and the same.

Avicenna

Avicenna argued for the distinctness of the soul and the body, and the incorruptibility of the former.

Aquinas

The full argument for the immortality of the soul and Thomas Aquinas' elaboration of Aristotelian theory is found in Question 75 of the First Part of the Summa Theologica.

Descartes

René Descartes

endorses the claim that the soul is simple, and also that this entails

that it cannot decompose. Descartes does not address the possibility

that the soul might suddenly disappear.

Leibniz

In early work, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

endorses a version of the argument from the simplicity of the soul to

its immortality, but like his predecessors, he does not address the

possibility that the soul might suddenly disappear. In his monadology he advances a sophisticated novel argument for the immortality of monads.

Moses Mendelssohn

Moses Mendelssohn's Phaedon

is a defense of the simplicity and immortality of the soul. It is a

series of three dialogues, revisiting the Platonic dialogue Phaedo, in which Socrates

argues for the immortality of the soul, in preparation for his own

death. Many philosophers, including Plotinus, Descartes, and Leibniz,

argue that the soul is simple, and that because simples cannot decompose

they must be immortal. In the Phaedon, Mendelssohn addresses gaps in

earlier versions of this argument (an argument that Kant calls the

Achilles of Rationalist Psychology). The Phaedon contains an original

argument for the simplicity of the soul, and also an original argument

that simples cannot suddenly disappear. It contains further original

arguments that the soul must retain its rational capacities as long as

it exists.

Ethics

The possibility of clinical immortality raises a host of medical,

philosophical, and religious issues and ethical questions. These include

persistent vegetative states, the nature of personality over time, technology to mimic or copy the mind or its processes, social and economic disparities created by longevity, and survival of the heat death of the universe.

Undesirability

Physical immortality has also been imagined as a form of eternal torment, as in Mary Shelley's short story "The Mortal Immortal", the protagonist of which witnesses everyone he cares about dying around him. Jorge Luis Borges explored the idea that life gets its meaning from death in the short story "The Immortal";

an entire society having achieved immortality, they found time becoming

infinite, and so found no motivation for any action. In his book Thursday's Fictions, and the stage and film adaptations of it, Richard James Allen

tells the story of a woman named Thursday who tries to cheat the cycle

of reincarnation to get a form of eternal life. At the end of this

fantastical tale, her son, Wednesday, who has witnessed the havoc his

mother's quest has caused, forgoes the opportunity for immortality when

it is offered to him. Likewise, the novel Tuck Everlasting depicts immortality as "falling off the wheel of life" and is viewed as a curse as opposed to a blessing. In the anime Casshern Sins

humanity achieves immortality due to advances in medical technology;

however, the inability of the human race to die causes Luna, a Messianic

figure, to come forth and offer normal lifespans because she believed

that without death, humans could not live. Ultimately, Casshern takes up

the cause of death for humanity when Luna begins to restore humanity's

immortality. In Anne Rice's book series The Vampire Chronicles, vampires

are portrayed as immortal and ageless, but their inability to cope with

the changes in the world around them means that few vampires live for

much more than a century, and those who do often view their changeless

form as a curse.

In his book Death, Yale philosopher Shelly Kagan

argues that any form of human immortality would be undesirable. Kagan's

argument takes the form of a dilemma. Either our characters remain

essentially the same in an immortal afterlife, or they do not. If our

characters remain basically the same—that is, if we retain more or less

the desires, interests, and goals that we have now—then eventually, over

an infinite stretch of time, we will get bored and find eternal life

unbearably tedious. If, on the other hand, our characters are radically

changed—e.g., by God periodically erasing our memories or giving us

rat-like brains that never tire of certain simple pleasures—then such a

person would be too different from our current self for us to care much

what happens to them. Either way, Kagan argues, immortality is

unattractive. The best outcome, Kagan argues, would be for humans to

live as long as they desired and then to accept death gratefully as

rescuing us from the unbearable tedium of immortality.

Sociology

If human beings were to achieve immortality, there would most likely be a change in the worlds' social structures. Sociologists argue that human beings' awareness of their own mortality shapes their behavior.

With the advancements in medical technology in extending human life,

there may need to be serious considerations made about future social

structures. The world is already experiencing a global demographic shift of increasingly ageing populations with lower replacement rates.

The social changes that are made to accommodate this new population

shift may be able to offer insight on the possibility of an immortal

society.

Politics

Although some scientists state that radical life extension, delaying and stopping aging are achievable,

there are no international or national programs focused on stopping

aging or on radical life extension. In 2012 in Russia, and then in the

United States, Israel and the Netherlands, pro-immortality political

parties were launched. They aimed to provide political support to

anti-aging and radical life extension research and technologies and at

the same time transition to the next step, radical life extension, life

without aging, and finally, immortality and aim to make possible access

to such technologies to most currently living people.

Symbols

The ankh

There are numerous symbols representing immortality. The ankh is an Egyptian symbol of life that holds connotations of immortality when depicted in the hands of the gods and pharaohs, who were seen as having control over the journey of life. The Möbius strip in the shape of a trefoil knot

is another symbol of immortality. Most symbolic representations of

infinity or the life cycle are often used to represent immortality

depending on the context they are placed in. Other examples include the Ouroboros, the Chinese fungus of longevity, the ten kanji, the phoenix, the peacock in Christianity, and the colors amaranth (in Western culture) and peach (in Chinese culture).

Fiction

Immortality is a popular subject in fiction, as it explores humanity's deep-seated fears and comprehension of its own mortality. Immortal beings and species abound in fiction, especially fantasy fiction, and the meaning of "immortal" tends to vary. The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the first literary works, is primarily a quest of a hero seeking to become immortal.

Some fictional beings are completely immortal (or very nearly so)

in that they are immune to death by injury, disease and age. Sometimes

such powerful immortals can only be killed by each other, as is the case

with the Q from the Star Trek

series. Even if something can't be killed, a common plot device

involves putting an immortal being into a slumber or limbo, as is done

with Morgoth in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Silmarillion and the Dreaming God of Pathways Into Darkness. Storytellers often make it a point to give weaknesses to even the most indestructible of beings. For instance, Superman is supposed to be invulnerable, yet his enemies were able to exploit his now-infamous weakness: Kryptonite.

Many fictitious species are said to be immortal if they cannot

die of old age, even though they can be killed through other means, such

as injury. Modern fantasy elves often exhibit this form of immortality. Other creatures, such as vampires and the immortals in the film Highlander, can only die from beheading. The classic and stereotypical vampire is typically slain by one of several very specific means, including a silver bullet

(or piercing with other silver weapons), a stake through the heart

(perhaps made of consecrated wood), or by exposing them to sunlight.

The 2018 science fiction TV series Ad vitam explored the social impact of biological immortality.