Phylogenetic nomenclature, often called cladistic nomenclature, is a method of nomenclature for taxa in biology that uses phylogenetic definitions for taxon names as explained below. This contrasts with the traditional approach, in which taxon names are defined by a type, which can be a specimen or a taxon of lower rank, and a description in words. Phylogenetic nomenclature is currently not regulated, but the International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature (PhyloCode) is intended to regulate it once it is ratified.

Definitions

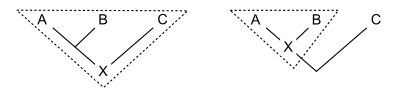

The

clade shown by the dashed lines in each figure is specified by the

ancestor X. Under the hypothesis that the relationships are as in the

left tree, the clade includes X, A, B and C. Under the hypothesis that

the relationships are as in the right tree, the clade includes X, A and

B.

Phylogenetic nomenclature ties names to clades, groups consisting of an ancestor and all its descendants. These groups can equivalently be called monophyletic.

There are slightly different ways of specifying the ancestor, which are

discussed below. Once the ancestor is specified, the meaning of the

name is fixed: the ancestor and all organisms which are its descendants

are included in the named taxon. Listing all these organisms (i.e.

providing a full circumscription) requires the full phylogenetic tree to be known. In practice, there are only one or more hypotheses

as to the correct tree. Different hypotheses lead to different

organisms being thought to be included in the named taxon, but do not

affect what organisms the name actually applies to. In this sense the

name is independent of theory revision.

Phylogenetic definitions of clade names

Phylogenetic nomenclature ties names to clades,

groups consisting solely of an ancestor and all its descendants. All

that is needed to specify a clade, therefore, is to designate the

ancestor. There are a number of ways of doing this. Commonly, the ancestor is indicated by its relation to two or more specifiers

(species, specimens, or traits) that are mentioned explicitly. The

diagram shows three common ways of doing this. For previously defined

clades A, B, and C, the clade X can be defined as:

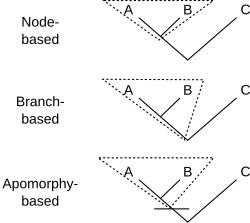

The

three most common ways to define the name of a clade: node-based,

branch-based and apomorphy-based definition. The tree represents a phylogenetic hypothesis on the relations of A, B and C.

- A node-based definition could read: "the last common ancestor of A and B, and all descendants of that ancestor". Thus, the entire line below the junction of A and B does not belong to the clade to which the name with this definition refers.

-

- Example: The sauropod dinosaurs consist of the last common ancestor of Vulcanodon (A) and Apatosaurus (B)[2] and all of that ancestor's descendants. This ancestor was the first sauropod. C could include other dinosaurs like Stegosaurus.

- A branch-based definition, often called a stem-based definition, could read: "the first ancestor of A which is not also an ancestor of C, and all descendants of that ancestor". Thus, the entire line below the junction of A and B (other than the bottommost point) does belong to the clade to which the name with this definition refers.

-

- Example: The rodents consist of the first ancestor of the house mouse (A) that is not also an ancestor of the eastern cottontail rabbit (C) together with all descendants of that ancestor. Here, the ancestor is the very first rodent. B is some other descendant, perhaps the red squirrel.

- An apomorphy-based definition could read: "the first ancestor of A to possess trait M that is inherited by A, and all descendants of that ancestor". In the diagram, M evolves at the intersection of the horizontal line with the tree. Thus, the clade to which the name with this definition refers contains that part of the line below the last common ancestor of A and B which corresponds to ancestors possessing the apomorphy M. The lower part of the line is excluded. It is not required that B have trait M; it may have disappeared in the lineage leading to B.

Several other alternatives are provided in the PhyloCode, (see below) though there is no attempt to be exhaustive.

Phylogenetic nomenclature allows the use, not only of ancestral relations, but also of the property of being extant. One of the many ways of specifying the Neornithes (modern birds), for example, is:

The Neornithes consist of the last common ancestor of the extant members of the most inclusive clade containing the cockatoo Cacatua galerita but not the dinosaur Stegosaurus armatus as well as all descendants of that ancestor.

Neornithes is a crown clade, a clade for which the last common ancestor of its extant members is also the last common ancestor of all its members.

Node names

- Crown node: Most recent common ancestor of the sampled species of the clade of interest

- Stem node: Most recent common ancestor of the clade of interest and its sister clade

Ancestry-based definitions of the names of paraphyletic and polyphyletic taxa

In the PhyloCode,

only a clade can receive a "phylogenetic definition", and this

restriction is observed in the present article. However, it is also

possible to create definitions for the names of other groups that are

phylogenetic in the sense that they use only ancestral relations

anchored on species or specimens.

For example, assuming Mammalia and Aves (birds) are defined in this

manner, Reptilia could be defined as "the most recent common ancestor of

Mammalia and Aves and all its descendants except Mammalia and Aves".

This is an example of a paraphyletic group, a clade minus one or more subordinate clades. Names of polyphyletic groups, characterized by a trait that evolved convergently in two or more subgroups, can similarly be defined as the sum of multiple clades.

Ranks

Under the traditional nomenclature codes, such as the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, taxa that are not explicitly associated with a rank

cannot be formally named, because the application of a name to a taxon

is based on both a type and a rank. The requirement for a rank is a

major difference between traditional and phylogenetic nomenclature. It

has several consequences: it limits the number of nested levels at which

names can be applied; it causes the endings of names to change if a

group has its rank changed, even if it has precisely the same members

(i.e. the same circumscription); and it is logically inconsistent with all taxa being monophyletic.

Especially in recent decades (due to advances in phylogenetics),

taxonomists have named many "nested" taxa (i.e. taxa which are

contained inside other taxa). No system of nomenclature attempts to name

every clade; this would be particularly difficult in traditional

nomenclature since every named taxon must be given a lower rank than any

named taxon in which it is nested, so the number of names that can be

assigned in a nested set of taxa can be no greater than the number of

generally recognized ranks. Gauthier et al. (1988)

suggested that, if Reptilia is assigned its traditional rank of class,

then a phylogenetic classification has to assign the rank of genus to

Aves.

In such a classification, all ~12,000 known species of extant and

extinct birds would then have to be incorporated into this genus.

Various solutions have been proposed while keeping the rank-based nomenclature codes. Patterson and Rosen (1977)

suggested nine new ranks between family and superfamily in order to be

able to classify a clade of herrings, and McKenna and Bell (1997)

introduced a large array of new ranks in order to cope with the

diversity of Mammalia; these have not been widely adopted. In botany,

the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group, responsible for the currently most widely used classification of flowering plants,

chose a different approach. They retained the traditional ranks of

family and order, considering them to be of value in teaching and in

studying relationships between taxa, but also introduced named clades

without formal ranks.

The current codes also have rules stating that names must have

certain endings depending on the rank of the taxa to which they are

applied. When a group has a different rank in different classifications,

its name must have a different suffix. Ereshefsky

gave an example. He noted that Simpson in 1963 and Wiley in 1981 agreed

that the same group of genera, which included the genus Homo,

should be placed together in a taxon. Simpson treated this taxon as a

family, and so gave it the name "Hominidae": "Homin-" from "Homo" and

"-idae" as the family ending under the zoological code. Wiley considered

it to be at the rank of tribe, and so gave it the name "Hominini",

"-ini" being the tribe ending. Wiley's tribe Hominini formed only part

of a family which he called "Hominidae". Thus, under the zoological

code, two groups with precisely the same circumscription were given

different names (Simpson's Hominidae and Wiley's Hominini) and two

groups with the same name had different circumscriptions (Simpson's

Hominidae and Wiley's Hominidae).

In phylogenetic nomenclature, ranks have no bearing on the spelling of taxon names (see e.g. Gauthier (1994) and the PhyloCode).

Ranks are, however, not altogether forbidden in phylogenetic

nomenclature. They are merely decoupled from nomenclature: they do not

influence which names can be used, which taxa are associated with which

names, and which names can refer to nested taxa.

The principles of traditional rank-based nomenclature are logically incompatible with all taxa being strictly monophyletic. Every organism must belong to a genus,

for example, so there would have to be a genus for every common

ancestor of the mammals and the birds. For such a genus to be

monophyletic, it would have to include both the class Mammalia and the class Aves. In rank-based nomenclature, however, classes must include genera, not the other way around.

Philosophy

The conflict between phylogenetic and traditional nomenclature reflects differing views of the metaphysics

of taxa. For the advocates of phylogenetic nomenclature, a taxon is an

individual, an entity that gains and loses attributes as time passes.

Just as a person does not become somebody else when his or her

properties change through maturation, senility, or more radical changes

like amnesia, the loss of a limb, or a change in sex, so a taxon remains

the same entity whatever characteristics are gained or lost.

For any individual, there has to be something that connects its

temporal stages in virtue of which it remains the same thing. For a

person, the spatiotemporal continuity of the body provides the relevant

connection; from infancy to old age, the body traces a continuous path

through the world and it is this path, rather than any characteristics

of the individual, that connects the baby and the octogenarian. For a taxon, if characteristics are not relevant, it can only be ancestral relations that connect the Devonian Rhyniognatha hirsti with the modern monarch butterfly as representatives, separated by 400 million years, of the taxon Insecta.

If ancestry is sufficient for the continuity of a taxon, however,

then all descendants of a taxon member will also be included in the

taxon, so all bona fide taxa are monophyletic; the names of paraphyletic

groups do not merit formal recognition. As "Pelycosauria"

refers to a paraphyletic group that includes some Permian tetrapods but

not their extant descendants, it cannot be admitted as a valid taxon

name.

To the adherent of traditional nomenclature, on the other hand, taxa are sets or classes. Unlike individuals, they are constituted by similarities, characteristics shared among their members.

Monophyletic groups are particularly worthy of attention and naming

primarily because they often share properties of interest. Since many

paraphyletic groups also share such properties, plesiomorphies

in their case, providing them with names is also conducive to

productive research. Such naming is strongly defended by some

scientists; in a 2005 letter to the editors of the journal Taxon, 150 biologists from around the world joined in defense of paraphyletic taxa. For Darwin, they pointed out, evolution involved descent and

modification, not just descent. Taxa, for them, are sets of organisms

united by similarity; when the similarity is too weak, descendants are

not in all of their ancestors' taxa.

History

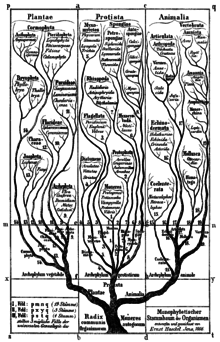

"Monophyletic phylogenetic tree of organisms".

Phylogenetic nomenclature is a result of the general acceptance of

branching in the course of evolution, represented in the diagrams of Jean-Baptiste Lamarck and later writers like Charles Darwin and Ernst Haeckel.

In 1866, Haeckel for the first time constructed a single tree of all

life and immediately proceeded to translate it into a classification.

This classification was rank-based, as was usual at the time, but did

not contain taxa that Haeckel considered polyphyletic. In it, Haeckel introduced the rank of phylum which carries a connotation of monophyly in its name (literally meaning "stem").

Ever since, it has been debated in which ways and to what extent

the phylogeny of life should be used as a basis for its classification,

with views ranging from "numerical taxonomy" (phenetics) over "evolutionary taxonomy"

(gradistics) to "phylogenetic systematics". From the 1960s onwards,

rankless classifications were occasionally proposed, but in general the

principles of rank-based nomenclature were used by all three schools of

thought.

Most of the basic tenets of phylogenetic nomenclature (lack of

obligatory ranks, and something close to phylogenetic definitions) can,

however, be traced to 1916, when Edwin Goodrich interpreted the name Sauropsida, erected 40 years earlier by T. H. Huxley, to include the birds (Aves) as well as part of Reptilia, and coined the new name Theropsida

to include the mammals as well as another part of Reptilia. Goodrich

did not give them ranks, and treated them exactly as if they had

phylogenetic definitions, using neither contents nor diagnostic

characters to decide whether a given animal should belong to Theropsida,

Sauropsida, or something else once its phylogenetic position was agreed

upon. Goodrich also opined that the name Reptilia should be abandoned

once the phylogeny of the reptiles would be better known.

The principle that only clades

should be formally named became popular in some circles in the second

half of the 20th century. It spread together with the methods for

discovering clades (cladistics)

and is an integral part of phylogenetic systematics (see above). At the

same time, it became apparent that the obligatory ranks that are part

of the traditional systems of nomenclature produced problems. Some

authors suggested abandoning them altogether, starting with Willi Hennig's abandonment of his earlier proposal to define ranks as geological age classes.

The first use of phylogenetic nomenclature in a publication can be dated to 1986.

Theoretical papers outlining the principles of phylogenetic

nomenclature, as well as further publications containing applications of

phylogenetic nomenclature (mostly to vertebrates), soon followed (see

Literature section).

In an attempt to avoid a schism in the biologist community, "Gauthier suggested to two members of the ICZN

to apply formal taxonomic names ruled by the zoological code only to

clades (at least for supraspecific taxa) and to abandon Linnean ranks,

but these two members promptly rejected these ideas" (Laurin, 2008:

224). This led Kevin de Queiroz and the botanist Philip Cantino to start drafting their own code of nomenclature, the PhyloCode, for regulating phylogenetic nomenclature.

Controversy

Willi Hennig's pioneering work provoked a spirited debate about the relative merits of phylogenetic nomenclature versus Linnaean taxonomy, or the related approach of evolutionary taxonomy, which has continued down to the present. Some of the debates in which the cladists were engaged had been running since the 19th century. While Hennig insisted that different classification schemes were useful for different purposes,

he gave primacy to his own, claiming that the categories of his system

had "individuality and reality" in contrast to the "timeless

abstractions" of morphology-based classifications.

Formal classifications based on cladistic reasoning are said to

emphasize ancestry at the expense of descriptive characteristics.

Nonetheless, most taxonomists today avoid paraphyletic groups whenever

they think it is possible within Linnaean taxonomy; polyphyletic taxa

have long fallen out of fashion.

The International Code of Phylogenetic Nomenclature

The ICPN, or PhyloCode, is a draft code of rules and recommendations for phylogenetic nomenclature.

- The ICPN will only regulate clade names. Names for para- or polyphyletic taxa, and names for species (which may or may not be clades), will not be considered, at least not at first. This means that the regulation of species names will be left, for the time being, to the rank-based codes of nomenclature.

- The Principle of Priority will be introduced for names and for definitions. The starting point for priority will be the publication date of the ICPN.

- Definitions for existing names, and new names along with their definitions, will have to be published in peer-reviewed works (on or after the starting date) and will have to be registered in an online database in order to be valid.

The number of supporters for widespread adoption of the PhyloCode is still small, and it is uncertain (as of December 2019) when the code will be implemented and how widely it will be followed.