A typical gasoline container.

Gasoline (American English), or petrol (British English), is a colorless petroleum-derived flammable liquid that is used primarily as a fuel in most spark-ignited internal combustion engines. It consists mostly of organic compounds obtained by the fractional distillation of petroleum, enhanced with a variety of additives. On average, a 42-U.S.-gallon (160-liter) barrel of crude oil yields about 19 U.S. gallons (72 liters) of gasoline (among other refined products) after processing in an oil refinery, though this varies based on the crude oil assay.

The characteristic of a particular gasoline blend to resist igniting too early (which causes knocking and reduces efficiency in reciprocating engines) is measured by its octane rating which is produced in several grades. Tetraethyl lead

and other lead compounds are no longer used in most areas to increase

octane rating (still used in aviation and auto-racing). Other chemicals

are frequently added to gasoline to improve chemical stability and

performance characteristics, control corrosiveness and provide fuel

system cleaning. Gasoline may contain oxygen-containing chemicals such

as ethanol, MTBE or ETBE to improve combustion.

Gasoline used in internal combustion engines can have significant

effects on the local environment, and is also a contributor to global

human carbon dioxide emissions. Gasoline can also enter the environment

uncombusted, both as liquid and as vapor, from leakage and handling

during production, transport and delivery (e.g., from storage tanks,

from spills, etc.). As an example of efforts to control such leakage,

many underground storage tanks are required to have extensive measures

in place to detect and prevent such leaks. Gasoline contains benzene and other known carcinogens.

Etymology

"Gasoline" is an English word that refers to fuel for automobiles. The Oxford English Dictionary

dates its first recorded use to 1863 when it was spelled "gasolene".

The term "gasoline" was first used in North America in 1864. The word is a derivation from the word "gas" and the chemical suffixes "-ol" and "-ine" or "-ene".

However, the term may also have been influenced by the trademark

"Cazeline" or "Gazeline". On 27 November 1862, the British publisher,

coffee merchant and social campaigner John Cassell placed an advertisement in The Times of London:

The Patent Cazeline Oil, safe, economical, and brilliant … possesses all the requisites which have so long been desired as a means of powerful artificial light.

This is the earliest occurrence of the word to have

been found. Cassell discovered that a shopkeeper in Dublin named Samuel

Boyd was selling counterfeit cazeline and wrote to him to ask him to

stop. Boyd did not reply and changed every ‘C’ into a ‘G’, thus coining

the word "gazeline".

In most Commonwealth

countries, the product is called "petrol", rather than "gasoline".

"Petrol" was first used in about 1870, as the name of a refined

petroleum product sold by British wholesaler Carless, Capel & Leonard, which marketed it as a solvent. When the product later found a new use as a motor fuel, Frederick Simms, an associate of Gottlieb Daimler, suggested to Carless that they register the trademark "petrol", but by that time the word was already in general use, possibly inspired by the French pétrole,

and the registration was not allowed. Carless registered a number of

alternative names for the product, but "petrol" nonetheless became the

common term for the fuel in the British Commonwealth.

British refiners originally used "motor spirit" as a generic name for the automotive fuel and "aviation spirit" for aviation gasoline.

When Carless was denied a trademark on "petrol" in the 1930s, its

competitors switched to the more popular name "petrol". However, "motor

spirit" had already made its way into laws and regulations, so the term

remains in use as a formal name for petrol. The term is used most widely in Nigeria, where the largest petroleum companies call their product "premium motor spirit".

Although "petrol" has made inroads into Nigerian English, "premium

motor spirit" remains the formal name that is used in scientific

publications, government reports, and newspapers.

The use of the word gasoline instead of petrol is uncommon outside North America, particularly given the usual shortening of gasoline to gas, because various forms of gaseous products are also used as automotive fuel, such as compressed natural gas (CNG), liquefied natural gas (LNG) and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG). In many languages, the name of the product is derived from benzene, such as Benzin in German or benzina in Italian. Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay use the colloquial name nafta derived from that of the chemical naphtha.

History

The first internal combustion engines suitable for use in transportation applications, so-called Otto engines,

were developed in Germany during the last quarter of the 19th century.

The fuel for these early engines was a relatively volatile hydrocarbon obtained from coal gas. With a boiling point near 85 °C (185 °F) (octane boils about 40 °C higher), it was well-suited for early carburetors

(evaporators). The development of a "spray nozzle" carburetor enabled

the use of less volatile fuels. Further improvements in engine

efficiency were attempted at higher compression ratios, but early attempts were blocked by the premature explosion of fuel, known as knocking.

In 1891, the Shukhov cracking process

became the world's first commercial method to break down heavier

hydrocarbons in crude oil to increase the percentage of lighter products

compared to simple distillation.

1903 to 1914

The

evolution of gasoline followed the evolution of oil as the dominant

source of energy in the industrializing world. Prior to World War One,

Britain was the world's greatest industrial power and depended on its

navy to protect the shipping of raw materials from its colonies. Germany

was also industrializing and, like Britain, lacked many natural

resources which had to be shipped to the home country. By the 1890s,

Germany began to pursue a policy of global prominence and began building

a navy to compete with Britain's. Coal was the fuel that powered their

navies. Though both Britain and Germany had natural coal reserves, new

developments in oil as a fuel for ships changed the situation.

Coal-powered ships were a tactical weakness because the process of loading coal

was extremely slow and dirty and left the ship completely vulnerable to

attack, and unreliable supplies of coal at international ports made

long-distance voyages impractical. The advantages of petroleum oil soon

found the navies of the world converting to oil, but Britain and Germany

had very few domestic oil reserves. Britain eventually solved its naval oil dependence by securing oil from Royal Dutch Shell and the Anglo-Persian Oil Company and this determined from where and of what quality its gasoline would come.

During the early period of gasoline engine development, aircraft

were forced to use motor vehicle gasoline since aviation gasoline did

not yet exist. These early fuels were termed "straight-run" gasolines

and were byproducts from the distillation of a single crude oil to

produce kerosene, which was the principal product sought for burning in kerosene lamps.

Gasoline production would not surpass kerosene production until 1916.

The earliest straight-run gasolines were the result of distilling

eastern crude oils and there was no mixing of distillates from different

crudes. The composition of these early fuels was unknown and the

quality varied greatly as crude oils from different oil fields emerged

in different mixtures of hydrocarbons in different ratios. The engine

effects produced by abnormal combustion (engine knocking and pre-ignition)

due to inferior fuels had not yet been identified, and as a result

there was no rating of gasoline in terms of its resistance to abnormal

combustion. The general specification by which early gasolines were

measured was that of specific gravity via the Baumé scale and later the volatility

(tendency to vaporize) specified in terms of boiling points, which

became the primary focuses for gasoline producers. These early eastern

crude oil gasolines had relatively high Baumé test results (65 to 80

degrees Baumé) and were called Pennsylvania "High-Test" or simply

"High-Test" gasolines. These would often be used in aircraft engines.

By 1910, increased automobile production and the resultant

increase in gasoline consumption produced a greater demand for gasoline.

Also, the growing electrification of lighting produced a drop in

kerosene demand, creating a supply problem. It appeared that the

burgeoning oil industry would be trapped into over-producing kerosene

and under-producing gasoline since simple distillation could not alter

the ratio of the two products from any given crude. The solution

appeared in 1911 when the development of the Burton process allowed thermal cracking

of crude oils, which increased the percent yield of gasoline from the

heavier hydrocarbons. This was combined with expansion of foreign

markets for the export of surplus kerosene which domestic markets no

longer needed. These new thermally "cracked" gasolines were believed to

have no harmful effects and would be added to straight-run gasolines.

There also was the practice of mixing heavy and light distillates to

achieve a desired Baumé reading and collectively these were called

"blended" gasolines.

Gradually, volatility gained favor over the Baumé test, though

both would continue to be used in combination to specify a gasoline. As

late as June 1917, Standard Oil

(the largest refiner of crude oil in the United States at the time)

stated that the most important property of a gasoline was its

volatility.

It is estimated that the rating equivalent of these straight-run

gasolines varied from 40 to 60 octane and that the "High-Test",

sometimes referred to as "fighting grade", probably averaged 50 to 65

octane.

World War I

Prior to the American entry into World War I,

the European Allies used fuels derived from crude oils from Borneo,

Java and Sumatra, which gave satisfactory performance in their military

aircraft. When the United States entered the war in April 1917, the U.S.

became the principal supplier of aviation gasoline to the Allies and a

decrease in engine performance was noted.

Soon it was realized that motor vehicle fuels were unsatisfactory for

aviation, and after the loss of a number of combat aircraft, attention

turned to the quality of the gasolines being used. Later flight tests

conducted in 1937 showed that an octane reduction of 13 points (from 100

down to 87 octane) decreased engine performance by 20 percent and

increased take-off distance by 45 percent.

If abnormal combustion were to occur, the engine could lose enough

power to make getting airborne impossible and a take-off roll became a

threat to the pilot and aircraft.

On 2 August 1917, the United States Bureau of Mines arranged to study fuels for aircraft in cooperation with the Aviation Section of the U.S. Army Signal Corps

and a general survey concluded that no reliable data existed for the

proper fuels for aircraft. As a result, flight tests began at Langley,

McCook and Wright fields to determine how different gasolines performed

under different conditions. These tests showed that in certain aircraft,

motor vehicle gasolines performed as well as "High-Test" but in other

types resulted in hot-running engines. It was also found that gasolines

from aromatic and naphthenic base crude oils from California, South

Texas and Venezuela resulted in smooth-running engines. These tests

resulted in the first government specifications for motor gasolines

(aviation gasolines used the same specifications as motor gasolines) in

late 1917.

United States, 1918–1929

Engine designers knew that, according to the Otto cycle,

power and efficiency increased with compression ratio, but experience

with early gasolines during World War I showed that higher compression

ratios increased the risk of abnormal combustion, producing lower power,

lower efficiency, hot-running engines and potentially severe engine

damage. To compensate for these poor fuels, early engines used low

compression ratios, which required relatively large, heavy engines to

produce limited power and efficiency. The Wright brothers'

first gasoline engine used a compression ratio as low as 4.7-to-1,

developed only 12 horsepower (8.9 kW) from 201 cubic inches (3,290 cc)

and weighed 180 pounds (82 kg).

This was a major concern for aircraft designers and the needs of the

aviation industry provoked the search for fuels that could be used in

higher-compression engines.

Between 1917 and 1919, the amount of thermally cracked gasoline utilized almost doubled. Also, the use of natural gasoline

increased greatly. During this period, many U.S. states established

specifications for motor gasoline but none of these agreed and were

unsatisfactory from one standpoint or another. Larger oil refiners began

to specify unsaturated

material percentage (thermally cracked products caused gumming in both

use and storage and unsaturated hydrocarbons are more reactive and tend

to combine with impurities leading to gumming). In 1922, the U.S.

government published the first specifications for aviation gasolines

(two grades were designated as "Fighting" and "Domestic" and were

governed by boiling points, color, sulphur content and a gum formation

test) along with one "Motor" grade for automobiles. The gum test

essentially eliminated thermally cracked gasoline from aviation usage

and thus aviation gasolines reverted to fractionating straight-run

naphthas or blending straight-run and highly treated thermally cracked

naphthas. This situation persisted until 1929.

The automobile industry reacted to the increase in thermally

cracked gasoline with alarm. Thermal cracking produced large amounts of

both mono- and diolefins (unsaturated hydrocarbons), which increased the risk of gumming. Also the volatility was decreasing to the point that fuel did not vaporize and was sticking to spark plugs

and fouling them, creating hard starting and rough running in winter

and sticking to cylinder walls, bypassing the pistons and rings and

going into the crankcase oil.

One journal stated, "...on a multi-cylinder engine in a high-priced car

we are diluting the oil in the crankcase as much as 40 percent in a

200-mile run, as the analysis of the oil in the oil-pan shows."

Being very unhappy with the consequent reduction in overall

gasoline quality, automobile manufacturers suggested imposing a quality

standard on the oil suppliers. The oil industry in turn accused the

automakers of not doing enough to improve vehicle economy, and the

dispute became known within the two industries as "The Fuel Problem".

Animosity grew between the industries, each accusing the other of not

doing anything to resolve matters, and relationships deteriorated. The

situation was only resolved when the American Petroleum Institute

(API) initiated a conference to address "The Fuel Problem" and a

Cooperative Fuel Research (CFR) Committee was established in 1920 to

oversee joint investigative programs and solutions. Apart from

representatives of the two industries, the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) also played an instrumental role, with the U.S. Bureau of Standards

being chosen as an impartial research organization to carry out many of

the studies. Initially, all the programs were related to volatility and

fuel consumption, ease of starting, crankcase oil dilution and

acceleration.

Leaded gasoline controversy, 1924–1925

With

the increased use of thermally cracked gasolines came an increased

concern regarding its effects on abnormal combustion, and this led to

research for antiknock additives. In the late 1910s, researchers such as

A.H. Gibson, Harry Ricardo, Thomas Midgley Jr. and Thomas Boyd began to investigate abnormal combustion. Beginning in 1916, Charles F. Kettering began investigating additives based on two paths, the "high percentage" solution (where large quantities of ethanol

were added) and the "low percentage" solution (where only 2–4 grams per

gallon were needed). The "low percentage" solution ultimately led to

the discovery of tetraethyllead (TEL) in December 1921, a product of the research of Midgley and Boyd. This innovation started a cycle of improvements in fuel efficiency

that coincided with the large-scale development of oil refining to

provide more products in the boiling range of gasoline. Ethanol could

not be patented but TEL could, so Kettering secured a patent for TEL and

began promoting it instead of other options.

The dangers of compounds containing lead

were well-established by then and Kettering was directly warned by

Robert Wilson of MIT, Reid Hunt of Harvard, Yandell Henderson of Yale,

and Charles Kraus of the University of Potsdam in Germany about its use.

Kraus had worked on tetraethyllead for many years and called it "a

creeping and malicious poison" that had killed a member of his

dissertation committee. On 27 October 1924, newspaper articles around the nation told of the workers at the Standard Oil refinery near Elizabeth, New Jersey who were producing TEL and were suffering from lead poisoning. By 30 October, the death toll had reached five.

In November, the New Jersey Labor Commission closed the Bayway refinery

and a grand jury investigation was started which had resulted in no

charges by February 1925. Leaded gasoline sales were banned in New York

City, Philadelphia and New Jersey. General Motors, DuPont, and Standard Oil, who were partners in Ethyl Corporation,

the company created to produce TEL, began to argue that there were no

alternatives to leaded gasoline that would maintain fuel efficiency and

still prevent engine knocking. After flawed studies determined that

TEL-treated gasoline was not a public health issue, the controversy

subsided.

United States, 1930–1941

In

the five-year period prior to 1929, a great amount of experimentation

was conducted on different testing methods for determining fuel

resistance to abnormal combustion. It appeared engine knocking was

dependent on a wide variety of parameters including compression,

cylinder temperature, air-cooled or water-cooled engines, chamber

shapes, intake temperatures, lean or rich mixtures and others. This led

to a confusing variety of test engines that gave conflicting results,

and no standard rating scale existed. By 1929, it was recognized by most

aviation gasoline manufacturers and users that some kind of antiknock

rating must be included in government specifications. In 1929, the octane rating scale was adopted, and in 1930 the first octane specification for aviation fuels was established. In the same year, the U.S. Army Air Force specified fuels rated at 87 octane for its aircraft as a result of studies it conducted.

During this period, research showed that hydrocarbon structure

was extremely important to the antiknocking properties of fuel.

Straight-chain paraffins in the boiling range of gasoline had low antiknock qualities while ring-shaped molecules such as aromatic hydrocarbons (an example is benzene) had higher resistance to knocking.

This development led to the search for processes that would produce

more of these compounds from crude oils than achieved under straight

distillation or thermal cracking. Research by the major refiners into

conversion processes yielded isomerization, dehydration, and alkylation

that could change the cheap and abundant butane into isooctane,

which became an important component in aviation fuel blending. To

further complicate the situation, as engine performance increased, the

altitude that aircraft could reach also increased, which resulted in

concerns about the fuel freezing. The average temperature decrease is

3.6 °F (2.0 °C) per 1,000-foot (300-metre) increase in altitude, and at

40,000 feet (12 km), the temperature can approach −70 °F (−57 °C).

Additives like benzene, with a freezing point of 42 °F (6 °C), would

freeze in the gasoline and plug fuel lines. Substitute aromatics such as

toluene, xylene and cumene combined with limited benzene solved the problem.

By 1935, there were seven different aviation grades based on

octane rating, two Army grades, four Navy grades and three commercial

grades including the introduction of 100-octane aviation gasoline. By

1937 the Army established 100-octane as the standard fuel for combat

aircraft and to add to the confusion, the government now recognized 14

different grades, in addition to 11 others in foreign countries. With

some companies required to stock 14 grades of aviation fuel, none of

which could be interchanged, the effect on the refiners was negative.

The refining industry could not concentrate on large capacity conversion

processes for so many different grades and a solution had to be found.

By 1941, principally through the efforts of the Cooperative Fuel

Research Committee, the number of grades for aviation fuels was reduced

to three: 73, 91 and 100 octane.

In 1937, Eugene Houdry developed the Houdry process of catalytic cracking,

which produced a high-octane base stock of gasoline which was superior

to the thermally cracked product since it did not contain the high

concentration of olefins.

In 1940, there were only 14 Houdry units in operation in the U.S.; by

1943, this had increased to 77, either of the Houdry process or of the

Thermofor Catalytic or Fluid Catalyst type.

The search for fuels with octane ratings above 100 led to the

extension of the scale by comparing power output. A fuel designated

grade 130 would produce 130 percent as much power in an engine as it

would running on pure iso-octane. During WW II, fuels above 100-octane

were given two ratings, a rich and lean mixture and these would be

called 'performance numbers' (PN). 100-octane aviation gasoline would be

referred to as 130/100 grade.

World War II

Germany

Oil

and its byproducts, especially high-octane aviation gasoline, would

prove to be a driving concern for how Germany conducted the war. As a

result of the lessons of World War I, Germany had stockpiled oil and

gasoline for its blitzkrieg

offensive and had annexed Austria, adding 18,000 barrels per day of oil

production, but this was not sufficient to sustain the planned conquest

of Europe. Because captured supplies and oil fields would be necessary

to fuel the campaign, the German high command created a special squad of

oil-field experts drawn from the ranks of domestic oil industries. They

were sent in to put out oil-field fires and get production going again

as soon as possible. But capturing oil fields remained an obstacle

throughout the war. During the Invasion of Poland, German estimates of gasoline consumption turned out to be vastly underestimated. Heinz Guderian and his Panzer divisions consumed nearly 1,000 U.S. gallons per mile (2,400 L/km) of gasoline on the drive to Vienna.

When they were engaged in combat across open country, gasoline

consumption almost doubled. On the second day of battle, a unit of the

XIX Corps was forced to halt when it ran out of gasoline.

One of the major objectives of the Polish invasion was their oil fields

but the Soviets invaded and captured 70 percent of the Polish

production before the Germans could reach it. Through the German-Soviet Commercial Agreement (1940),

Stalin agreed in vague terms to supply Germany with additional oil

equal to that produced by now Soviet-occupied Polish oil fields at

Drohobych and Boryslav in exchange for hard coal and steel tubing.

Even after the Nazis conquered the vast territories of Europe,

this did not help the gasoline shortage. This area had never been

self-sufficient in oil before the war. In 1938, the area that would

become Nazi-occupied would produce 575,000 barrels per day. In 1940,

total production under German control amounted to only 234,550 barrels

(37,290 m3)—a shortfall of 59 percent. By the spring of 1941 and the depletion of German gasoline reserves, Adolf Hitler

saw the invasion of Russia to seize the Polish oil fields and the

Russian oil in the Caucasus as the solution to the German gasoline

shortage. As early as July 1941, following the 22 June start of Operation Barbarossa,

certain Luftwaffe squadrons were forced to curtail ground support

missions due to shortages of aviation gasoline. On 9 October, the German

quartermaster general estimated that army vehicles were 24,000 barrels

(3,800 m3) barrels short of gasoline requirements.

Virtually all of Germany's aviation gasoline came from synthetic

oil plants that hydrogenated coals and coal tars. These processes had

been developed during the 1930s as an effort to achieve fuel

independence. There were two grades of aviation gasoline produced in

volume in Germany, the B-4 or blue grade and the C-3 or green grade,

which accounted for about two-thirds of all production. B-4 was

equivalent to 89-octane and the C-3 was roughly equal to the U.S.

100-octane, though lean mixture was rated around 95-octane and was

poorer than the U.S. Maximum output achieved in 1943 reached 52,200

barrels a day before the Allies decided to target the synthetic fuel

plants. Through captured enemy aircraft and analysis of the gasoline

found in them, both the Allies and the Axis powers were aware of the

quality of the aviation gasoline being produced and this prompted an

octane race to achieve the advantage in aircraft performance. Later in

the war the C-3 grade was improved to where it was equivalent to the

U.S. 150 grade (rich mixture rating).

Japan

Japan, like

Germany, had almost no domestic oil supply and by the late 1930s

produced only 7% of its own oil while importing the rest – 80% from the

United States. As Japanese aggression grew in China (USS Panay incident)

and news reached the American public of Japanese bombing of civilian

centers, especially the bombing of Chungking, public opinion began to

support a U.S. embargo. A Gallup poll in June 1939 found that 72 percent

of the American public supported an embargo on war materials to Japan.

This increased tensions between the U.S. and Japan led to the U.S.

placing restrictions on exports and in July 1940 the U.S. issued a

proclamation that banned the export of 87 octane or higher aviation

gasoline to Japan. This ban did not hinder the Japanese as their

aircraft could operate with fuels below 87 octane and if needed they

could add TEL

to increase the octane. As it turned out, Japan bought 550 percent more

sub-87 octane aviation gasoline in the five months after the July 1940

ban on higher octane sales.

The possibility of a complete ban of gasoline from America created

friction in the Japanese government as to what action to take to secure

more supplies from the Dutch East Indies and demanded greater oil

exports from the exiled Dutch government after the Battle of the Netherlands.

This action prompted the U.S. to move its Pacific fleet from Southern

California to Pearl Harbor to help stiffen British resolve to stay in

Indochina. With the Japanese invasion of French Indochina

in September 1940 came great concerns about the possible Japanese

invasion of the Dutch Indies to secure their oil. After the U.S. banned

all exports of steel and iron scrap, the next day Japan signed the Tripartite Pact

and this led Washington to fear that a complete U.S. oil embargo would

prompt the Japanese to invade the Dutch East Indies. On 16 June 1941

Harold Ickes, who was appointed Petroleum Coordinator for National

Defense, stopped a shipment of oil from Philadelphia to Japan in light

of the oil shortage on the East coast due to increased exports to

Allies. He also telegrammed all oil suppliers on the East coast not to

ship any oil to Japan without his permission. President Roosevelt

countermanded Ickes' orders telling Ickes that the "... I simply have

not got enough Navy to go around and every little episode in the Pacific

means fewer ships in the Atlantic".

On 25 July 1941 the U.S. froze all Japanese financial assets and

licenses would be required for each use of the frozen funds including

oil purchases that could produce aviation gasoline. On 28 July 1941

Japan invaded southern Indochina.

The debate inside the Japanese government as to its oil and

gasoline situation was leading to invasion of the Dutch East Indies but

this would mean war with the U.S. whose Pacific fleet was a threat to

their flank. This situation led to the decision to attack the U.S. fleet

at Pearl Harbor before proceeding with the Dutch East Indies invasion.

On 7 December 1941 Japan attacked Pearl Harbor and the next day the

Netherlands declared war on Japan which initiated the Dutch East Indies campaign.

But the Japanese missed a golden opportunity at Pearl Harbor. "All of

the oil for the fleet was in surface tanks at the time of Pearl Harbor,"

Admiral Chester Nimitz, who became Commander in Chief of the Pacific

Fleet, was later to say. "We had about 4 1⁄2 million barrels [720,000 m3]

of oil out there and all of it was vulnerable to .50 caliber bullets.

Had the Japanese destroyed the oil," he added, "it would have prolonged

the war another two years."

United States

Early

in 1944, William Boyd, president of the American Petroleum Institute

and chairman of the Petroleum Industry War Council said: "The Allies may

have floated to victory on a wave of oil in World War I, but in this

infinitely greater World War II, we are flying to victory on the wings

of petroleum". In December, 1941 the United States had 385,000 oil wells

producing 1.4 billion barrels of oil a year and 100-octane aviation

gasoline capacity was at 40,000 barrels a day. By 1944 the U.S. was

producing over 1.5 billion barrels a year (67 percent of world

production) and the petroleum industry had built 122 new plants for the

production of 100-octane aviation gasoline and capacity was over 400,000

barrels a day – an increase of more than ten-fold. It was estimated

that the U.S. was producing enough 100-octane aviation gasoline to

permit the dropping of 20,000 tons of bombs on the enemy every day of

the year. The record of gasoline consumption by the Army prior to June,

1943 was uncoordinated as each supply service of the Army purchased its

own petroleum products and no centralized system of control nor records

existed. On 1 June 1943 the Army created the Fuels and Lubricants

Division of the Quartermaster Corps and from their records they

tabulated that the Army (excluding fuels and lubricants for aircraft)

purchased over 2.4 billion gallons of gasoline for delivery to overseas

theaters between 1 June 1943 through August, 1945. That figure does not

include gasoline used by the Army inside the United States. Motor fuel production had declined from 701,000,000 barrels in 1941 down to 608,000,000 barrels in 1943.

World War II marked the first time in U.S. history that gasoline was

rationed and the government imposed price controls to prevent inflation.

Gasoline consumption per automobile declined from 755 gallons per year

in 1941 down to 540 gallons in 1943 with the goal of preserving rubber

for tires since the Japanese had cut the U.S. off from over 90 percent

of its rubber supply which had come from the Dutch East Indies and the

U.S. synthetic rubber industry was in its infancy. Average gasoline

prices went from an all-time record low of $0.1275 per gallon ($0.1841

with taxes) in 1940 to $0.1448 per gallon ($0.2050 with taxes) in 1945.

Even with the world's largest aviation gasoline production, the

U.S. military still found that more was needed. Throughout the duration

of the war, aviation gasoline supply was always behind requirements and

this impacted training and operations. The reason for this shortage

developed before the war even began. The free market did not support the

expense of producing 100-octane aviation fuel in large volume,

especially during the Great Depression. Iso-octane in the early

development stage cost $30 a gallon and even by 1934 it was still $2 a

gallon compared to $0.18 for motor gasoline when the Army decided to

experiment with 100-octane for its combat aircraft. Though only 3

percent of U.S. combat aircraft in 1935 could take full advantage of the

higher octane due to low compression ratios, the Army saw the need for

increasing performance warranted the expense and purchased 100,000

gallons. By 1937 the Army established 100-octane as the standard fuel

for combat aircraft and by 1939 production was only 20,000 barrels a

day. In effect, the U.S. military was the only market for 100-octane

aviation gasoline and as war broke out in Europe this created a supply

problem that persisted throughout the duration.

With the war in Europe in 1939 a reality, all predictions of

100-octane consumption were outrunning all possible production. Neither

the Army nor the Navy could contract more than six months in advance

for fuel and they could not supply the funds for plant expansion.

Without a long term guaranteed market the petroleum industry would not

risk its capital to expand production for a product that only the

government would buy. The solution to the expansion of storage,

transportation, finances and production was the creation of the Defense

Supplies Corporation on 19 September 1940. The Defense Supplies

Corporation would buy, transport and store all aviation gasoline for the

Army and Navy at cost plus a carrying fee.

When the Allied breakout after D-Day found their armies

stretching their supply lines to a dangerous point, the makeshift

solution was the Red Ball Express.

But even this soon was inadequate. The trucks in the convoys had to

drive longer distances as the armies advanced and they were consuming a

greater percentage of the same gasoline they were trying to deliver. In

1944, General George Patton's Third Army finally stalled just short of

the German border after running out of gasoline. The general was so

upset at the arrival of a truckload of rations instead of gasoline he

was reported to have shouted: "Hell, they send us food, when they know

we can fight without food but not without oil."

The solution had to wait for the repairing of the railroad lines and

bridges so that the more efficient trains could replace the gasoline

consuming truck convoys.

United States, 1946 to present

The

development of jet engines burning kerosene-based fuels during WW II

for aircraft produced a superior performing propulsion system than

internal combustion engines could offer and the U.S. military forces

gradually replaced their piston combat aircraft with jet powered planes.

This development would essentially remove the military need for ever

increasing octane fuels and eliminated government support for the

refining industry to pursue the research and production of such exotic

and expensive fuels. Commercial aviation was slower to adapt to jet

propulsion and until 1958 when the Boeing 707

first entered commercial service, piston powered airliners still relied

on aviation gasoline. But commercial aviation had greater economic

concerns than the maximum performance that the military could afford. As

octane numbers increased so did the cost of gasoline but the

incremental increase in efficiency becomes less as compression ratio

goes up. This reality set a practical limit to how high compression

ratios could increase relative to how expensive the gasoline would

become. Last produced in 1955, the Pratt & Whitney R-4360 Wasp Major

was using 115/145 Aviation gasoline and producing 1 horsepower per

cubic inch at 6.7 compression ratio (turbo-supercharging would increase

this) and 1 pound of engine weight to produce 1.1 horsepower. This

compares to the Wright Brothers engine needing almost 17 pounds of

engine weight to produce 1 horsepower.

The US automobile industry after WWII could not take advantage of

the high octane fuels then available. Automobile compression ratios

increased from an average of 5.3-to-1 in 1931 to just 6.7-to-1 in 1946.

The average octane number of regular grade motor gasoline increased from

58 to 70 during the same time. Military aircraft were using expensive

turbo-supercharged engines that cost at least 10 times as much per

horsepower as automobile engines and had to be overhauled every 700 to

1,000 hours. The automobile market could not support such expensive

engines.

It would not be until 1957 that the first US automobile manufacturer

could mass-produce an engine that would produce one horsepower per cubic

inch, the Chevrolet 283 hp/283 cubic inch V-8 engine option in the

Corvette. At $485 this was an expensive option that few consumers could

afford and would only appeal to the performance oriented consumer market

willing to pay for the premium fuel required.

This engine had an advertised compression ratio of 10.5-to-1 and the

1958 AMA Specifications stated the octane requirement was 96-100 RON.

At 535 pounds (243 kg) (1959 with aluminum intake), it took 1.9 pounds

(0.86 kg) of engine weight to make 1 horsepower (0.75 kW).

In the 1950s oil refineries started to focus on high octane

fuels, and then detergents were added to gasoline to clean the jets in

carburetors. The 1970s witnessed greater attention to the environmental

consequences of burning gasoline. These considerations led to the

phasing out of TEL and its replacement by other antiknock compounds.

Subsequently, low-sulfur gasoline was introduced, in part to preserve

the catalysts in modern exhaust systems.

Chemical analysis and production

Some of the main components of gasoline: isooctane, butane, 3-ethyltoluene, and the octane enhancer MTBE

A pumpjack in the United States

An oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico

Gasoline is produced in oil refineries. Roughly 19 U.S. gallons (72 L) of gasoline is derived from a 42-U.S.-gallon (160 L) barrel of crude oil. Material separated from crude oil via distillation, called virgin or straight-run gasoline, does not meet specifications for modern engines (particularly the octane rating; see below), but can be pooled to the gasoline blend.

The bulk of a typical gasoline consists of a homogeneous mixture of small, relatively lightweight hydrocarbons with between 4 and 12 carbon atoms per molecule (commonly referred to as C4–C12). It is a mixture of paraffins (alkanes), olefins (alkenes) and cycloalkanes (naphthenes). The usage of the terms paraffin and olefin in place of the standard chemical nomenclature alkane and alkene, respectively, is particular to the oil industry. The actual ratio of molecules in any gasoline depends upon:

- the oil refinery that makes the gasoline, as not all refineries have the same set of processing units;

- the crude oil feed used by the refinery;

- the grade of gasoline (in particular, the octane rating).

The various refinery streams blended to make gasoline have different characteristics. Some important streams include:

- straight-run gasoline, commonly referred to as naphtha, which is distilled directly from crude oil. Once the leading source of fuel, its low octane rating required lead additives. It is low in aromatics (depending on the grade of the crude oil stream) and contains some cycloalkanes (naphthenes) and no olefins (alkenes). Between 0 and 20 percent of this stream is pooled into the finished gasoline, because the supply of this fraction is insufficient and its RON is straight-run gasoline, commonly referred to as naphtha, which is distilled directly from crude oil. Once the leading source of fuel, its low octane rating required lead additives. It is low in aromatics (depending on the grade of the crude oil stream) and contains some cycloalkanes (naphthenes) and no olefins (alkenes). Between 0 and 20 percent of this stream is pooled into the finishedtoo low. The chemical properties (namely RON and Reid vapor pressure) of the straight-run gasoline can be improved through reforming and isomerisation. However, before feeding those units, the naphtha needs to be split into light and heavy naphtha. Straight-run gasoline can also be used as a feedstock for steam-crackers to produce olefins.

- reformate, produced in a catalytic reformer, has a high octane rating with high aromatic content and relatively low olefin content. Most of the benzene, toluene and xylene (the so-called BTX hydrocarbons) are more valuable as chemical feedstocks and are thus removed to some extent.

- catalytic cracked gasoline, or catalytic cracked naphtha, produced with a catalytic cracker, has a moderate octane rating, high olefin content and moderate aromatic content.

- hydrocrackate (heavy, mid and light), produced with a hydrocracker, has a medium to low octane rating and moderate aromatic levels.

- alkylate is produced in an alkylation unit, using isobutane and olefins as feedstocks. Finished alkylate contains no aromatics or olefins and has a high MON.

- isomerate is obtained by isomerizing low-octane straight-run gasoline into iso-paraffins (non-chain alkanes, such as isooctane). Isomerate has a medium RON and MON, but no aromatics or olefins.

- butane is usually blended in the gasoline pool, although the quantity of this stream is limited by the RVP specification.

The terms above are the jargon used in the oil industry and terminology varies.

Currently, many countries set limits on gasoline aromatics

in general, benzene in particular, and olefin (alkene) content. Such

regulations have led to an increasing preference for high-octane pure

paraffin (alkane) components, such as alkylate, and are forcing

refineries to add processing units to reduce benzene content. In the

European Union, the benzene limit is set at 1% by volume for all grades

of automotive gasoline.

Gasoline can also contain other organic compounds, such as organic ethers (deliberately added), plus small levels of contaminants, in particular organosulfur compounds (which are usually removed at the refinery).

Physical properties

Density

The specific gravity of gasoline is from 0.71 to 0.77, with higher densities having a greater volume of aromatics.

Finished marketable gasoline is traded (in Europe) with a standard

reference of 0.755 kg/L (6.30 lb/US gal), and its price is escalated or

de-escalated according to its actual density.

Because of its low density, gasoline floats on water, and so water

cannot generally be used to extinguish a gasoline fire unless applied in

a fine mist.

Stability

Quality

gasoline should be stable for six months if stored properly, but as

gasoline is a mixture rather than a single compound, it will break down

slowly over time due to the separation of the components. Gasoline

stored for a year will most likely be able to be burned in an internal

combustion engine without too much trouble but the effects of long-term

storage will become more noticeable with each passing month until a time

comes when the gasoline should be diluted with ever-increasing amounts

of freshly made fuel so that the older gasoline may be used up. If left

undiluted, improper operation will occur and this may include engine

damage from misfiring or the lack of proper action of the fuel within a fuel injection

system and from an onboard computer attempting to compensate (if

applicable to the vehicle). Gasoline should ideally be stored in an

airtight container (to prevent oxidation or water vapor mixing in with the gas) that can withstand the vapor pressure

of the gasoline without venting (to prevent the loss of the more

volatile fractions) at a stable cool temperature (to reduce the excess

pressure from liquid expansion and to reduce the rate of any

decomposition reactions). When gasoline is not stored correctly, gums

and solids may result, which can corrode system components and

accumulate on wetted surfaces, resulting in a condition called "stale

fuel". Gasoline containing ethanol is especially subject to absorbing

atmospheric moisture, then forming gums, solids or two phases (a

hydrocarbon phase floating on top of a water-alcohol phase).

The presence of these degradation products in the fuel tank or

fuel lines plus a carburetor or fuel injection components makes it

harder to start the engine or causes reduced engine performance. On

resumption of regular engine use, the buildup may or may not be

eventually cleaned out by the flow of fresh gasoline. The addition of a

fuel stabilizer to gasoline can extend the life of fuel that is not or

cannot be stored properly, though removal of all fuel from a fuel system

is the only real solution to the problem of long-term storage of an

engine or a machine or vehicle. Typical fuel stabilizers are proprietary

mixtures containing mineral spirits, isopropyl alcohol, 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene or other additives.

Fuel stabilizers are commonly used for small engines, such as lawnmower

and tractor engines, especially when their use is sporadic or seasonal

(little to no use for one or more seasons of the year). Users have been

advised to keep gasoline containers more than half full and properly

capped to reduce air exposure, to avoid storage at high temperatures, to

run an engine for ten minutes to circulate the stabilizer through all

components prior to storage, and to run the engine at intervals to purge

stale fuel from the carburetor.

Gasoline stability requirements are set by the standard ASTM

D4814. This standard describes the various characteristics and

requirements of automotive fuels for use over a wide range of operating

conditions in ground vehicles equipped with spark-ignition engines.

Energy content

A

gasoline-fueled internal combustion engine obtains energy from the

combustion of gasoline's various hydrocarbons with oxygen from the

ambient air, yielding carbon dioxide and water as exhaust. The combustion of octane, a representative species, performs the chemical reaction:

By weight, gasoline contains about 46.7 MJ/kg (13.0 kWh/kg; 21.2 MJ/lb) or by volume 33.6 megajoules per litre (9.3 kWh/l; 127 MJ/US gal; 121,000 Btu/US gal), quoting the lower heating value.

Gasoline blends differ, and therefore actual energy content varies

according to the season and producer by up to 1.75% more or less than

the average.

On average, about 74 L (19.5 US gal; 16.3 imp gal) of gasoline are

available from a barrel of crude oil (about 46% by volume), varying with

the quality of the crude and the grade of the gasoline. The remainder

are products ranging from tar to naphtha.

A high-octane-rated fuel, such as liquefied petroleum gas (LPG), has an overall lower power output at the typical 10:1 compression ratio of an engine design optimized for gasoline fuel. An engine tuned for LPG

fuel via higher compression ratios (typically 12:1) improves the power

output. This is because higher-octane fuels allow for a higher

compression ratio without knocking, resulting in a higher cylinder

temperature, which improves efficiency. Also, increased mechanical

efficiency is created by a higher compression ratio through the

concomitant higher expansion ratio on the power stroke, which is by far

the greater effect. The higher expansion ratio extracts more work from

the high-pressure gas created by the combustion process. An Atkinson cycle

engine uses the timing of the valve events to produce the benefits of a

high expansion ratio without the disadvantages, chiefly detonation, of a

high compression ratio. A high expansion ratio is also one of the two

key reasons for the efficiency of diesel engines, along with the elimination of pumping losses due to throttling of the intake air flow.

The lower energy content of LPG by liquid volume in comparison to

gasoline is due mainly to its lower density. This lower density is a

property of the lower molecular weight of propane

(LPG's chief component) compared to gasoline's blend of various

hydrocarbon compounds with heavier molecular weights than propane.

Conversely, LPG's energy content by weight is higher than gasoline's due

to a higher hydrogen-to-carbon ratio.

Molecular weights of the representative octane combustion are C8H18 114, O2 32, CO2 44, H2O 18; therefore 1 kg of fuel reacts with 3.51 kg of oxygen to produce 3.09 kg of carbon dioxide and 1.42 kg of water.

Octane rating

Spark-ignition engines are designed to burn gasoline in a controlled process called deflagration. However, the unburned mixture may autoignite by pressure and heat alone, rather than igniting from the spark plug at exactly the right time, causing a rapid pressure rise which can damage the engine. This is often referred to as engine knocking or end-gas knock. Knocking can be reduced by increasing the gasoline's resistance to autoignition, which is expressed by its octane rating.

Octane rating is measured relative to a mixture of 2,2,4-trimethylpentane (an isomer of octane) and n-heptane.

There are different conventions for expressing octane ratings, so the

same physical fuel may have several different octane ratings based on

the measure used. One of the best known is the research octane number

(RON).

The octane rating of typical commercially available gasoline varies by country. In Finland, Sweden and Norway, 95 RON is the standard for regular unleaded gasoline and 98 RON is also available as a more expensive option.

In the United Kingdom, ordinary regular unleaded gasoline is sold

at 95 RON (commonly available), premium unleaded gasoline is always 97

RON, and super-unleaded is usually 97–98 RON.] However, both Shell and BP produce fuel at 102 RON for cars with high-performance engines, and in 2006 the supermarket chain Tesco began to sell super-unleaded gasoline rated at 99 RON.

In the United States, octane ratings in unleaded fuels vary between 85

and 87 AKI (91–92 RON) for regular, 89–90 AKI (94–95 RON) for mid-grade

(equivalent to European regular), up to 90–94 AKI (95–99 RON) for

premium (European premium).

As South Africa's largest city, Johannesburg, is located on the Highveld at 1,753 metres (5,751 ft) above sea level, the Automobile Association of South Africa

recommends 95-octane gasoline at low altitude and 93-octane for use in

Johannesburg because "The higher the altitude the lower the air

pressure, and the lower the need for a high octane fuel as there is no

real performance gain".

Octane rating became important as the military sought higher output for aircraft engines in the late 1930s and the 1940s. A higher octane rating allows a higher compression ratio or supercharger boost, and thus higher temperatures and pressures, which translate to higher power output. Some scientists[] even predicted that a nation with a good supply of high-octane gasoline would have the advantage in air power. In 1943, the Rolls-Royce Merlin aero engine produced 1,320 horsepower (984 kW) using 100 RON fuel from a modest 27-liter displacement. By the time of Operation Overlord, both the RAF and USAAF were conducting some operations in Europe using 150 RON fuel (100/150 avgas), obtained by adding 2.5% aniline to 100-octane avgas. By this time the Rolls-Royce Merlin 66 was developing 2,000 hp using this fuel.

Additives

Antiknock additives

A plastic container for storing gasoline used in Germany

Almost all countries in the world have phased out automotive leaded fuel. In 2011, six countries were still using leaded gasoline: Afghanistan, Myanmar, North Korea, Algeria, Iraq and Yemen. It was expected that by the end of 2013 those countries, too, would ban leaded gasoline, but this target was not met. Algeria replaced leaded with unleaded automotive fuel only in 2015. Different additives have replaced the lead compounds. The most popular additives include aromatic hydrocarbons, ethers and alcohol (usually ethanol or methanol). For technical reasons, the use of leaded additives is still permitted worldwide for the formulation of some grades of aviation gasoline such as 100LL, because the required octane rating would be technically infeasible to reach without the use of leaded additives.

A gas can

Tetraethyllead

Gasoline, when used in high-compression internal combustion engines, tends to autoignite or "detonate" causing damaging engine knocking (also called "pinging" or "pinking"). To address this problem, tetraethyllead

(TEL) was widely adopted as an additive for gasoline in the 1920s. With

the discovery of the seriousness of the extent of environmental and

health damage caused by lead compounds, however, and the incompatibility

of lead with catalytic converters, governments began to mandate reductions in gasoline lead.

In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency

issued regulations to reduce the lead content of leaded gasoline over a

series of annual phases, scheduled to begin in 1973 but delayed by

court appeals until 1976. By 1995, leaded fuel accounted for only 0.6

percent of total gasoline sales and under 2000 short tons (1814 t) of lead per year. From 1 January 1996, the U.S. Clean Air Act

banned the sale of leaded fuel for use in on-road vehicles in the U.S.

The use of TEL also necessitated other additives, such as dibromoethane.

European countries began replacing lead-containing additives by

the end of the 1980s, and by the end of the 1990s, leaded gasoline was

banned within the entire European Union.

Reduction in the average lead content of human blood is believed

to be a major cause for falling violent crime rates around the world,

including in the United States and South Africa.

A statistically significant correlation has been found between the

usage rate of leaded gasoline and violent crime: taking into account a

22-year time lag, the violent crime curve virtually tracks the lead

exposure curve.

Lead replacement petrol

Lead

replacement petrol (LRP) was developed for vehicles designed to run on

leaded fuels and incompatible with unleaded fuels. Rather than

tetraethyllead it contains other metals such as potassium compounds or methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl

(MMT); these are purported to buffer soft exhaust valves and seats so

that they do not suffer recession due to the use of unleaded fuel.

LRP was marketed during and after the phaseout of leaded motor fuels in the United Kingdom, Australia, South Africa and some other countries. Consumer confusion led to a widespread mistaken preference for LRP rather than unleaded, and LRP was phased out 8 to 10 years after the introduction of unleaded.

Leaded gasoline was withdrawn from sale in Britain after 31 December 1999, seven years after EEC

regulations signaled the end of production for cars using leaded

gasoline in member states. At this stage, a large percentage of cars

from the 1980s and early 1990s which ran on leaded gasoline were still

in use, along with cars which could run on unleaded fuel. However, the

declining number of such cars on British roads saw many gasoline

stations withdrawing LRP from sale by 2003.

MMT

Methylcyclopentadienyl manganese tricarbonyl (MMT) is used in Canada and the US to boost octane rating. It also helps old cars designed for leaded fuel run on unleaded fuel without the need for additives to prevent valve problems. Its use in the United States has been restricted by regulations. Its use in the European Union is restricted by Article 8a of the Fuel Quality Directive

following its testing under the Protocol for the evaluation of effects

of metallic fuel-additives on the emissions performance of vehicles.

Fuel stabilizers (antioxidants and metal deactivators)

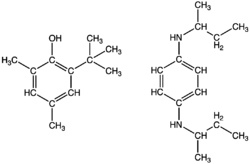

Substituted phenols and derivatives of phenylenediamine are common antioxidants used to inhibit gum formation in gasoline

Gummy, sticky resin deposits result from oxidative degradation of gasoline during long-term storage. These harmful deposits arise from the oxidation of alkenes and other minor components in gasoline (see drying oils).

Improvements in refinery techniques have generally reduced the

susceptibility of gasolines to these problems. Previously, catalytically

or thermally cracked gasolines were most susceptible to oxidation. The

formation of gums is accelerated by copper salts, which can be

neutralized by additives called metal deactivators.

This degradation can be prevented through the addition of 5–100 ppm of antioxidants, such as phenylenediamines and other amines. Hydrocarbons with a bromine number of 10 or above can be protected with the combination of unhindered or partially hindered phenols and oil-soluble strong amine bases, such as hindered phenols. "Stale" gasoline can be detected by a colorimetric enzymatic test for organic peroxides produced by oxidation of the gasoline.

Gasolines are also treated with metal deactivators,

which are compounds that sequester (deactivate) metal salts that

otherwise accelerate the formation of gummy residues. The metal

impurities might arise from the engine itself or as contaminants in the

fuel.

Detergents

Gasoline, as delivered at the pump, also contains additives to reduce internal engine carbon buildups, improve combustion and allow easier starting in cold climates. High levels of detergent can be found in Top Tier Detergent Gasolines. The specification for Top Tier Detergent Gasolines was developed by four automakers: GM, Honda, Toyota, and BMW. According to the bulletin, the minimal U.S. EPA requirement is not sufficient to keep engines clean. Typical detergents include alkylamines and alkyl phosphates at the level of 50–100 ppm.

Ethanol

European Union

In the EU, 5% ethanol

can be added within the common gasoline spec (EN 228). Discussions are

ongoing to allow 10% blending of ethanol (available in Finnish, French

and German gas stations). In Finland, most gasoline stations sell 95E10,

which is 10% ethanol, and 98E5, which is 5% ethanol. Most gasoline sold

in Sweden has 5–15% ethanol added. Three different ethanol blends are

sold in the Netherlands—E5, E10 and hE15. The last of these differs from

standard ethanol–gasoline blends in that it consists of 15% hydrous ethanol (i.e., the ethanol–water azeotrope) instead of the anhydrous ethanol traditionally used for blending with gasoline.

Brazil

The Brazilian National Agency of Petroleum, Natural Gas and Biofuels (ANP) requires gasoline for automobile use to have 27.5% of ethanol added to its composition. Pure hydrated ethanol is also available as a fuel.

Australia

Legislation

requires retailers to label fuels containing ethanol on the dispenser,

and limits ethanol use to 10% of gasoline in Australia. Such gasoline is

commonly called E10 by major brands, and it is cheaper than regular unleaded gasoline.

United States

The federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) effectively requires refiners and blenders to blend renewable biofuels

(mostly ethanol) with gasoline, sufficient to meet a growing annual

target of total gallons blended. Although the mandate does not require a

specific percentage of ethanol, annual increases in the target combined

with declining gasoline consumption

has caused the typical ethanol content in gasoline to approach 10%.

Most fuel pumps display a sticker that states that the fuel may contain

up to 10% ethanol, an intentional disparity that reflects the varying

actual percentage. Until late 2010, fuel retailers were only authorized

to sell fuel containing up to 10 percent ethanol (E10), and most vehicle

warranties (except for flexible fuel vehicles) authorize fuels that

contain no more than 10 percent ethanol. In parts of the United States, ethanol is sometimes added to gasoline without an indication that it is a component.

India

In October 2007, the Government of India

decided to make 5% ethanol blending (with gasoline) mandatory.

Currently, 10% ethanol blended product (E10) is being sold in various

parts of the country. Ethanol has been found in at least one study to damage catalytic converters.

Dyes

Though gasoline is a naturally colorless liquid, many gasolines are

dyed in various colors to indicate their composition and acceptable

uses. In Australia, the lowest grade of gasoline (RON 91) was dyed a

light shade of red/orange and is now the same colour as the medium grade

(RON 95) and high octane (RON 98) which are dyed yellow. In the United States, aviation gasoline (avgas) is dyed to identify its octane rating and to distinguish it from kerosene-based jet fuel, which is clear. In Canada, the gasoline for marine and farm use is dyed red and is not subject to sales tax.

Oxygenate blending

Oxygenate blending adds oxygen-bearing compounds such as MTBE, ETBE, TAME, TAEE, ethanol and biobutanol. The presence of these oxygenates reduces the amount of carbon monoxide

and unburned fuel in the exhaust. In many areas throughout the U.S.,

oxygenate blending is mandated by EPA regulations to reduce smog and

other airborne pollutants. For example, in Southern California, fuel

must contain 2% oxygen by weight, resulting in a mixture of 5.6% ethanol

in gasoline. The resulting fuel is often known as reformulated gasoline

(RFG) or oxygenated gasoline, or in the case of California, California reformulated gasoline. The federal requirement that RFG contain oxygen was dropped on 6 May 2006 because the industry had developed VOC-controlled RFG that did not need additional oxygen.

MTBE was phased out in the U.S. due to groundwater contamination

and the resulting regulations and lawsuits. Ethanol and, to a lesser

extent, the ethanol-derived ETBE are common substitutes. A common

ethanol-gasoline mix of 10% ethanol mixed with gasoline is called gasohol or E10, and an ethanol-gasoline mix of 85% ethanol mixed with gasoline is called E85. The most extensive use of ethanol takes place in Brazil, where the ethanol is derived from sugarcane.

In 2004, over 3.4 billion US gallons (2.8 billion imp gal; 13 million

m³) of ethanol was produced in the United States for fuel use, mostly

from corn,

and E85 is slowly becoming available in much of the United States,

though many of the relatively few stations vending E85 are not open to

the general public.

The use of bioethanol

and bio-methanol, either directly or indirectly by conversion of

ethanol to bio-ETBE, or methanol to bio-MTBE is encouraged by the

European Union Directive on the Promotion of the use of biofuels and other renewable fuels for transport. Since producing bioethanol from fermented sugars and starches involves distillation,

though, ordinary people in much of Europe cannot legally ferment and

distill their own bioethanol at present (unlike in the U.S., where

getting a BATF distillation permit has been easy since the 1973 oil crisis).

Safety

HAZMAT class 3 gasoline

Environmental considerations

Combustion of 1 U.S. gallon (3.8 L) of gasoline produces 8.74 kilograms (19.3 lb) of carbon dioxide (2.3 kg/l), a greenhouse gas.

The main concern with gasoline on the environment, aside from the complications of its extraction and refining, is the effect on the climate through the production of carbon dioxide. Unburnt gasoline and evaporation from the tank, when in the atmosphere, reacts in sunlight to produce photochemical smog. Vapor pressure initially rises with some addition of ethanol to gasoline, but the increase is greatest at 10% by volume.

At higher concentrations of ethanol above 10%, the vapor pressure of

the blend starts to decrease. At a 10% ethanol by volume, the rise in

vapor pressure may potentially increase the problem of photochemical

smog. This rise in vapor pressure could be mitigated by increasing or

decreasing the percentage of ethanol in the gasoline mixture.

The chief risks of such leaks come not from vehicles, but from

gasoline delivery truck accidents and leaks from storage tanks. Because

of this risk, most (underground) storage tanks now have extensive

measures in place to detect and prevent any such leaks, such as

monitoring systems (Veeder-Root, Franklin Fueling).

Production of gasoline consumes 0.63 gallons of water per mile driven.

Toxicity

The safety data sheet for a 2003 Texan unleaded gasoline shows at least 15 hazardous chemicals occurring in various amounts, including benzene (up to 5% by volume), toluene (up to 35% by volume), naphthalene (up to 1% by volume), trimethylbenzene (up to 7% by volume), methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) (up to 18% by volume, in some states) and about ten others. Hydrocarbons in gasoline generally exhibit low acute toxicities, with LD50 of 700–2700 mg/kg for simple aromatic compounds. Benzene and many antiknocking additives are carcinogenic.

People can be exposed to gasoline in the workplace by swallowing

it, breathing in vapors, skin contact, and eye contact. Gasoline is

toxic. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) has also designated gasoline as a carcinogen.

Physical contact, ingestion or inhalation can cause health problems.

Since ingesting large amounts of gasoline can cause permanent damage to

major organs, a call to a local poison control center or emergency room

visit is indicated.

Contrary to common misconception, swallowing gasoline does not

generally require special emergency treatment, and inducing vomiting

does not help, and can make it worse. According to poison specialist

Brad Dahl, "even two mouthfuls wouldn't be that dangerous as long as it

goes down to your stomach and stays there or keeps going." The US CDC's Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry says not to induce vomiting, lavage, or administer activated charcoal.

Inhalation for intoxication

Inhaled (huffed)

gasoline vapor is a common intoxicant. Users concentrate and inhale

gasoline vapour in a manner not intended by the manufacturer to produce euphoria and intoxication.

Gasoline inhalation has become epidemic in some poorer communities and

indigenous groups in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and some Pacific

Islands. The practice is thought to cause severe organ damage, including mental retardation.

In Canada, Native children in the isolated Northern Labrador community of Davis Inlet were the focus of national concern in 1993, when many were found to be sniffing gasoline. The Canadian and provincial Newfoundland and Labrador

governments intervened on a number of occasions, sending many children

away for treatment. Despite being moved to the new community of Natuashish in 2002, serious inhalant abuse problems have continued. Similar problems were reported in Sheshatshiu in 2000 and also in Pikangikum First Nation. In 2012, the issue once again made the news media in Canada.

Australia has long faced a petrol (gasoline) sniffing problem in isolated and impoverished aboriginal communities. Although some sources argue that sniffing was introduced by United States servicemen stationed in the nation's Top End during World War II or through experimentation by 1940s-era Cobourg Peninsula sawmill workers, other sources claim that inhalant abuse (such as glue inhalation) emerged in Australia in the late 1960s. Chronic, heavy petrol sniffing appears to occur among remote, impoverished indigenous communities, where the ready accessibility of petrol has helped to make it a common substance for abuse.

In Australia, petrol sniffing now occurs widely throughout remote Aboriginal communities in the Northern Territory, Western Australia, northern parts of South Australia and Queensland.

The number of people sniffing petrol goes up and down over time as

young people experiment or sniff occasionally. "Boss", or chronic,

sniffers may move in and out of communities; they are often responsible

for encouraging young people to take it up. In 2005, the Government of Australia and BP Australia began the usage of Opal fuel in remote areas prone to petrol sniffing.

Opal is a non-sniffable fuel (which is much less likely to cause a

high) and has made a difference in some indigenous communities.

Flammability

Uncontrolled burning of gasoline produces large quantities of soot and carbon monoxide.

Like other hydrocarbons, gasoline burns in a limited range of its

vapor phase and, coupled with its volatility, this makes leaks highly

dangerous when sources of ignition are present. Gasoline has a lower explosive limit of 1.4% by volume and an upper explosive limit

of 7.6%. If the concentration is below 1.4%, the air-gasoline mixture

is too lean and does not ignite. If the concentration is above 7.6%, the

mixture is too rich and also does not ignite. However, gasoline vapor

rapidly mixes and spreads with air, making unconstrained gasoline

quickly flammable.

Use and pricing

The United States accounts for about 44% of the world's gasoline consumption. In 2003, the United States consumed 476 gigaliters (126 billion U.S. gallons; 105 billion imperial gallons),

which equates to 1.3 gigaliters (340 million U.S. gallons; 290 million

imperial gallons) of gasoline each day. The United States used about 510

gigaliters (130 billion U.S. gallons; 110 billion imperial gallons) of

gasoline in 2006, of which 5.6% was mid-grade and 9.5% was premium

grade.

Europe

Countries in Europe impose substantially higher taxes

on fuels such as gasoline when compared to the United States. The price

of gasoline in Europe is typically higher than that in the U.S. due to

this difference.

United States

US Regular Gasoline Prices through 2018

From 1998 to 2004, the price of gasoline fluctuated between US$1 and US$2 per U.S. gallon.

After 2004, the price increased until the average gas price reached a

high of $4.11 per U.S. gallon in mid-2008, but receded to approximately

$2.60 per U.S. gallon by September 2009. More recently, the U.S. experienced an upswing in gasoline prices through 2011, and by 1 March 2012, the national average was $3.74 per gallon.

In the United States, most consumer goods bear pre-tax prices,

but gasoline prices are posted with taxes included. Taxes are added by

federal, state, and local governments. As of 2009, the federal tax is

18.4¢ per gallon for gasoline and 24.4¢ per gallon for diesel (excluding red diesel). Among individual states, the highest gasoline tax rates, including the federal taxes as of October 2018, are found in Pennsylvania (77.1¢/gal), California (73.93¢/gal), and Washington (67.8¢/gal).

About 9 percent of all gasoline sold in the U.S. in May 2009 was

premium grade, according to the Energy Information Administration. Consumer Reports magazine says, "If [your owner’s manual] says to use regular fuel, do so—there's no advantage to a higher grade." The Associated Press

said premium gas—which has a higher octane rating and costs more per

gallon than regular unleaded—should be used only if the manufacturer

says it is "required". Cars with turbocharged

engines and high compression ratios often specify premium gas because

higher octane fuels reduce the incidence of "knock", or fuel

pre-detonation. The price of gas varies considerably between the summer and winter months.

Gasoline production by country

| Country | Gasoline production |

|---|---|

| USA | 9571 |

| China | 2578 |

| Japan | 920 |

| Russia | 910 |

| India | 755 |

| Canada | 671 |

| Brazil | 533 |

| Germany | 465 |

| Saudi Arabia | 441 |

| Mexico | 407 |

| South Korea | 397 |

| Iran | 382 |

| UK | 364 |

| Italy | 343 |

| Venezuela | 277 |

| France | 265 |

| Singapore | 249 |

| Australia | 241 |

| Indonesia | 230 |

| Taiwan | 174 |

| Thailand | 170 |

| Spain | 169 |

| Netherlands | 148 |

| South Africa | 135 |

| Argentina | 122 |

| Sweden | 112 |

| Greece | 108 |

| Belgium | 105 |

| Malaysia | 103 |

| Finland | 100 |

| Belarus | 92 |

| Turkey | 92 |

| Colombia | 85 |

| Poland | 83 |

| Norway | 77 |

| Kazakhstan | 71 |

| Algeria | 70 |

| Romania | 70 |

| Oman | 69 |

| Egypt | 66 |

| UA Emirates | 66 |

| Chile | 65 |

| Turkmenistan | 61 |

| Kuwait | 57 |

| Iraq | 56 |

| Vietnam | 52 |

| Lithuania | 49 |

| Denmark | 48 |

| Qatar | 46 |

Carbon dioxide production

About 19.64 pounds (8.91 kg) of carbon dioxide (CO2)

are produced from burning 1 U.S. gallon (3.8 liters) of gasoline that

does not contain ethanol (2.36 kg/L). About 22.38 pounds (10.15 kg) of

CO2 are produced from burning one US gallon of diesel fuel (2.69 kg/l).

The U.S. EIA

estimates that U.S. motor gasoline and diesel (distillate) fuel

consumption for transportation in 2015 resulted in the emission of about

1,105 million metric tons of CO2 and 440 million metric tons of CO2, respectively, for a total of 1,545 million metric tons of CO2. This total was equivalent to 83% of total U.S. transportation-sector CO2 emissions and equivalent to 29% of total U.S. energy-related CO2 emissions in 2015.

Most of the retail gasoline now sold in the United States contains about 10% fuel ethanol (or E10) by volume. Burning a gallon of E10 produces about 17.68 pounds (8.02 kg) of CO2 that is emitted from the fossil fuel content. If the CO2 emissions from ethanol combustion are considered, then about 18.95 pounds (8.60 kg) of CO2 are produced when a gallon of E10 is combusted. About 12.73 pounds (5.77 kg) of CO2 are produced when a gallon of pure ethanol is combusted.