Electrophysiology (from Greek ἥλεκτρον, ēlektron, "amber" [see the etymology of "electron"]; φύσις, physis, "nature, origin"; and -λογία, -logia) is the branch of physiology that studies the electrical properties of biological cells and tissues. It involves measurements of voltage changes or electric current or manipulations on a wide variety of scales from single ion channel proteins to whole organs like the heart. In neuroscience, it includes measurements of the electrical activity of neurons, and, in particular, action potential activity. Recordings of large-scale electric signals from the nervous system, such as electroencephalography, may also be referred to as electrophysiological recordings. They are useful for electrodiagnosis and monitoring.

"Current

Clamp" is a common technique in electrophysiology. This is a whole-cell

current clamp recording of a neuron firing due to it being depolarized

by current injection

Definition and scope

Classical electrophysiological techniques

Principle and mechanisms

Electrophysiology is the branch of physiology that pertains broadly to the flow of ions (ion current)

in biological tissues and, in particular, to the electrical recording

techniques that enable the measurement of this flow. Classical

electrophysiology techniques involve placing electrodes into various preparations of biological tissue. The principal types of electrodes are:

- simple solid conductors, such as discs and needles (singles or arrays, often insulated except for the tip),

- tracings on printed circuit boards or flexible polymers, also insulated except for the tip, and

- hollow tubes filled with an electrolyte, such as glass pipettes filled with potassium chloride solution or another electrolyte solution.

The principal preparations include:

- living organisms,

- excised tissue (acute or cultured),

- dissociated cells from excised tissue (acute or cultured),

- artificially grown cells or tissues, or

- hybrids of the above.

Neuronal electrophysiology is the study of electrical properties of

biological cells and tissues within the nervous system. With neuronal

electrophysiology doctors and specialists can determine how neuronal

disorders happen, by looking at the individual's brain activity.

Activity such as which portions of the brain light up during any

situations encountered.

If an electrode is small enough (micrometers) in diameter, then the electrophysiologist may choose to insert the tip into a single cell. Such a configuration allows direct observation and recording of the intracellular

electrical activity of a single cell. However, this invasive setup

reduces the life of the cell and causes a leak of substances across the

cell membrane. Intracellular activity may also be observed using a

specially formed (hollow) glass pipette containing an electrolyte. In

this technique, the microscopic pipette tip is pressed against the cell

membrane, to which it tightly adheres by an interaction between glass

and lipids of the cell membrane. The electrolyte within the pipette may

be brought into fluid continuity with the cytoplasm by delivering a

pulse of negative pressure to the pipette in order to rupture the small

patch of membrane encircled by the pipette rim (whole-cell recording).

Alternatively, ionic continuity may be established by "perforating" the

patch by allowing exogenous pore-forming agent within the electrolyte

to insert themselves into the membrane patch (perforated patch recording). Finally, the patch may be left intact (patch recording).

The electrophysiologist may choose not to insert the tip into a

single cell. Instead, the electrode tip may be left in continuity with

the extracellular space. If the tip is small enough, such a

configuration may allow indirect observation and recording of action potentials from a single cell, termed single-unit recording.

Depending on the preparation and precise placement, an extracellular

configuration may pick up the activity of several nearby cells

simultaneously, termed multi-unit recording.

As electrode size increases, the resolving power decreases.

Larger electrodes are sensitive only to the net activity of many cells,

termed local field potentials.

Still larger electrodes, such as uninsulated needles and surface

electrodes used by clinical and surgical neurophysiologists, are

sensitive only to certain types of synchronous activity within

populations of cells numbering in the millions.

Other classical electrophysiological techniques include single channel recording and amperometry.

Electrographic modalities by body part

Electrophysiological recording in general is sometimes called electrography (from electro- + -graphy, "electrical recording"), with the record thus produced being an electrogram. However, the word electrography has other senses (including electrophotography), and the specific types of electrophysiological recording are usually called by specific names, constructed on the pattern of electro- + [body part combining form] + -graphy (abbreviation ExG). Relatedly, the word electrogram (not being needed for those other senses)

often carries the specific meaning of intracardiac electrogram, which

is like an electrocardiogram but with some invasive leads (inside the

heart) rather than only noninvasive leads (on the skin).

Electrophysiological recording for clinical diagnostic purposes is included within the category of electrodiagnostic testing. The various "ExG" modes are as follows:

| Modality | Abbreviation | Body part | Prevalence in clinical use |

|---|---|---|---|

| electrocardiography | ECG or EKG | heart (specifically, the cardiac muscle), with cutaneous electrodes (noninvasive) | 1—very common |

| electroatriography | EAG | atrial cardiac muscle | 3—uncommon |

| electroventriculography | EVG | ventricular cardiac muscle | 3—uncommon |

| intracardiac electrogram | EGM | heart (specifically, the cardiac muscle), with intracardiac electrodes (invasive) | 2—somewhat common |

| electroencephalography | EEG | brain (usually the cerebral cortex), with extracranial electrodes | 2—somewhat common |

| electrocorticography | ECoG or iEEG | brain (specifically the cerebral cortex), with intracranial electrodes | 2—somewhat common |

| electromyography | EMG | muscles throughout the body (usually skeletal, occasionally smooth) | 1—very common |

| electrooculography | EOG | eye—entire globe | 2—somewhat common |

| electroretinography | ERG | eye—retina specifically | 2—somewhat common |

| electronystagmography | ENG | eye—via the corneoretinal potential | 2—somewhat common |

| electroolfactography | EOG | olfactory epithelium in mammals | 3—uncommon |

| electroantennography | EAG | olfactory receptors in arthropod antennae | 4—not applicable clinically |

| electrocochleography | ECOG or ECochG | cochlea | 2—somewhat common |

| electrogastrography | EGG | stomach smooth muscle | 2—somewhat common |

| electrogastroenterography | EGEG | stomach and bowel smooth muscle | 2—somewhat common |

| electroglottography | EGG | glottis | 3—uncommon |

| electropalatography | EPG | palatal contact of tongue | 3—uncommon |

| electroarteriography | EAG | arterial flow via streaming potential detected through skin[2] | 3—uncommon |

| electroblepharography | EBG | eyelid muscle | 3—uncommon |

| electrodermography | EDG | skin | 3—uncommon |

| electrohysterography | EHG | uterus | 3—uncommon |

| electroneuronography | ENeG or ENoG | nerves | 3—uncommon |

| electropneumography | EPG | lungs (chest movements) | 3—uncommon |

| electrospinography | ESG | spinal cord | 3—uncommon |

| electrovomerography | EVG | vomeronasal organ | 3—uncommon |

Optical electrophysiological techniques

Optical

electrophysiological techniques were created by scientists and

engineers to overcome one of the main limitations of classical

techniques. Classical techniques allow observation of electrical

activity at approximately a single point within a volume of tissue.

Essentially, classical techniques singularize a distributed phenomenon.

Interest in the spatial distribution of bioelectric activity prompted

development of molecules capable of emitting light in response to their

electrical or chemical environment. Examples are voltage sensitive dyes and fluorescing proteins.

After introducing one or more such compounds into tissue via perfusion,

injection or gene expression, the 1 or 2-dimensional distribution of

electrical activity may be observed and recorded.

Intracellular recording

Intracellular recording

involves measuring voltage and/or current across the membrane of a

cell. To make an intracellular recording, the tip of a fine (sharp)

microelectrode must be inserted inside the cell, so that the membrane potential

can be measured. Typically, the resting membrane potential of a

healthy cell will be -60 to -80 mV, and during an action potential the

membrane potential might reach +40 mV.

In 1963, Alan Lloyd Hodgkin and Andrew Fielding Huxley

won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contribution to

understanding the mechanisms underlying the generation of action

potentials in neurons. Their experiments involved intracellular

recordings from the giant axon

of Atlantic squid (Loligo pealei), and were among the first

applications of the "voltage clamp" technique.

Today, most microelectrodes used for intracellular recording are glass

micropipettes, with a tip diameter of < 1 micrometre, and a

resistance of several megohms. The micropipettes are filled with a

solution that has a similar ionic composition to the intracellular fluid

of the cell. A chlorided silver wire inserted into the pipet connects

the electrolyte electrically to the amplifier and signal processing

circuit. The voltage measured by the electrode is compared to the

voltage of a reference electrode, usually a silver chloride-coated

silver wire in contact with the extracellular fluid around the cell. In

general, the smaller the electrode tip, the higher its electrical resistance,

so an electrode is a compromise between size (small enough to penetrate

a single cell with minimum damage to the cell) and resistance (low

enough so that small neuronal signals can be discerned from thermal

noise in the electrode tip).

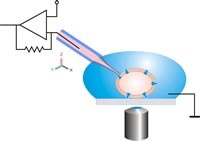

Voltage clamp

The

voltage clamp uses a negative feedback mechanism. The membrane

potential amplifier measures membrane voltage and sends output to the

feedback amplifier. The feedback amplifier subtracts the membrane

voltage from the command voltage, which it receives from the signal

generator. This signal is amplified and returned into the cell via the

recording electrode.

The voltage clamp technique allows an experimenter to "clamp" the cell potential at a chosen value. This makes it possible to measure how much ionic current crosses a cell's membrane at any given voltage. This is important because many of the ion channels in the membrane of a neuron are voltage-gated ion channels,

which open only when the membrane voltage is within a certain range.

Voltage clamp measurements of current are made possible by the

near-simultaneous digital subtraction of transient capacitive currents

that pass as the recording electrode and cell membrane are charged to

alter the cell's potential.

Current clamp

The current clamp technique records the membrane potential

by injecting current into a cell through the recording electrode.

Unlike in the voltage clamp mode, where the membrane potential is held

at a level determined by the experimenter, in "current clamp" mode the

membrane potential is free to vary, and the amplifier records whatever

voltage the cell generates on its own or as a result of stimulation.

This technique is used to study how a cell responds when electric

current enters a cell; this is important for instance for understanding

how neurons respond to neurotransmitters that act by opening membrane ion channels.

Most current-clamp amplifiers provide little or no amplification

of the voltage changes recorded from the cell. The "amplifier" is

actually an electrometer,

sometimes referred to as a "unity gain amplifier"; its main purpose is

to reduce the electrical load on the small signals (in the mV range)

produced by cells so that they can be accurately recorded by low-impedance

electronics. The amplifier increases the current behind the signal

while decreasing the resistance over which that current passes.

Consider this example based on Ohm's law: A voltage of 10 mV is

generated by passing 10 nanoamperes of current across 1 MΩ of resistance. The electrometer changes this "high impedance signal" to a "low impedance signal" by using a voltage follower circuit. A voltage follower reads the voltage on the input (caused by a small current through a big resistor).

It then instructs a parallel circuit that has a large current source

behind it (the electrical mains) and adjusts the resistance of that

parallel circuit to give the same output voltage, but across a lower

resistance.

Patch-clamp recording

The cell-attached patch clamp uses a micropipette attached to the cell membrane to allow recording from a single ion channel.

This technique was developed by Erwin Neher and Bert Sakmann who received the Nobel Prize in 1991.

Conventional intracellular recording involves impaling a cell with a

fine electrode; patch-clamp recording takes a different approach. A

patch-clamp microelectrode is a micropipette with a relatively large tip

diameter. The microelectrode is placed next to a cell, and gentle

suction is applied through the microelectrode to draw a piece of the

cell membrane (the 'patch') into the microelectrode tip; the glass tip

forms a high resistance 'seal' with the cell membrane. This

configuration is the "cell-attached" mode, and it can be used for

studying the activity of the ion channels that are present in the patch

of membrane.

If more suction is now applied, the small patch of membrane in the

electrode tip can be displaced, leaving the electrode sealed to the rest

of the cell. This "whole-cell" mode allows very stable intracellular

recording. A disadvantage (compared to conventional intracellular

recording with sharp electrodes) is that the intracellular fluid of the

cell mixes with the solution inside the recording electrode, and so some

important components of the intracellular fluid can be diluted. A

variant of this technique, the "perforated patch" technique, tries to

minimise these problems.

Instead of applying suction to displace the membrane patch from the

electrode tip, it is also possible to make small holes on the patch with

pore-forming agents so that large molecules such as proteins can stay

inside the cell and ions can pass through the holes freely. Also the

patch of membrane can be pulled away from the rest of the cell. This

approach enables the membrane properties of the patch to be analysed

pharmacologically.

Sharp electrode recording

In

situations where one wants to record the potential inside the cell

membrane with minimal effect on the ionic constitution of the

intracellular fluid a sharp electrode can be used. These micropipettes

(electrodes) are again like those for patch clamp pulled from glass

capillaries, but the pore is much smaller so that there is very little

ion exchange between the intracellular fluid and the electrolyte in the

pipette. The resistance of the micropipette electrode is tens or

hundreds of MΩ. Often the tip of the electrode is filled with various kinds of dyes like Lucifer yellow

to fill the cells recorded from, for later confirmation of their

morphology under a microscope. The dyes are injected by applying a

positive or negative, DC or pulsed voltage to the electrodes depending

on the polarity of the dye.

Extracellular recording

Single-unit recording

An electrode introduced into the brain of a living animal will detect

electrical activity that is generated by the neurons adjacent to the

electrode tip. If the electrode is a microelectrode, with a tip size of

about 1 micrometre, the electrode will usually detect the activity of at

most one neuron. Recording in this way is in general called

"single-unit" recording. The action potentials recorded are very much

like the action potentials that are recorded intracellularly, but the

signals are very much smaller (typically about 1 mV). Most recordings of

the activity of single neurons in anesthetized and conscious animals

are made in this way. Recordings of single neurons in living animals

have provided important insights into how the brain processes

information. For example, David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel recorded the activity of single neurons in the primary visual cortex of the anesthetized cat, and showed how single neurons in this area respond to very specific features of a visual stimulus. Hubel and Wiesel were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1981.

Multi-unit recording

If

the electrode tip is slightly larger, then the electrode might record

the activity generated by several neurons. This type of recording is

often called "multi-unit recording", and is often used in conscious

animals to record changes in the activity in a discrete brain area

during normal activity. Recordings from one or more such electrodes that

are closely spaced can be used to identify the number of cells around

it as well as which of the spikes come from which cell. This process is

called spike sorting

and is suitable in areas where there are identified types of cells with

well defined spike characteristics.

If the electrode tip is bigger still, in general the activity of

individual neurons cannot be distinguished but the electrode will still

be able to record a field potential generated by the activity of many

cells.

Field potentials

A schematic diagram showing a field potential recording from rat hippocampus. At the left is a schematic diagram of a presynaptic terminal

and postsynaptic neuron. This is meant to represent a large population

of synapses and neurons. When the synapse releases glutamate onto the

postsynaptic cell, it opens ionotropic glutamate receptor channels. The

net flow of current is inward, so a current sink is generated. A

nearby electrode (#2) detects this as a negativity. An intracellular electrode placed inside the cell body (#1) records the change in membrane potential that the incoming current causes.

Extracellular field potentials

are local current sinks or sources that are generated by the collective

activity of many cells. Usually, a field potential is generated by the

simultaneous activation of many neurons by synaptic transmission.

The diagram to the right shows hippocampal synaptic field potentials.

At the right, the lower trace shows a negative wave that corresponds to

a current sink caused by positive charges entering cells through

postsynaptic glutamate receptors,

while the upper trace shows a positive wave that is generated by the

current that leaves the cell (at the cell body) to complete the circuit.

For more information, see local field potential.

Amperometry

Amperometry

uses a carbon electrode to record changes in the chemical composition

of the oxidized components of a biological solution. Oxidation and

reduction is accomplished by changing the voltage at the active surface

of the recording electrode in a process known as "scanning". Because

certain brain chemicals lose or gain electrons at characteristic

voltages, individual species can be identified. Amperometry has been

used for studying exocytosis in the nervous and endocrine systems. Many

monoamine neurotransmitters; e.g., norepinephrine (noradrenalin), dopamine, and serotonin

(5-HT) are oxidizable. The method can also be used with cells that do

not secrete oxidizable neurotransmitters by "loading" them with 5-HT or

dopamine.

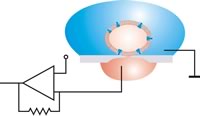

Planar patch clamp

Planar patch clamp is a novel method developed for high throughput electrophysiology. Instead of positioning a pipette on an adherent cell, cell suspension is pipetted on a chip containing a microstructured aperture.

A single cell is then positioned on the hole by suction and a tight connection (Gigaseal) is formed.

The planar geometry offers a variety of advantages compared to the classical experiment:

- It allows for integration of microfluidics, which enables automatic compound application for ion channel screening.

- The system is accessible for optical or scanning probe techniques.

- Perfusion of the intracellular side can be performed.

- Scanning electron microscope image of a planar patch clamp chip. Both the pipette and the chip are made from borosilicate glass.

Other methods

Solid-supported membrane (SSM)-based

With this electrophysiological approach, proteoliposomes, membrane vesicles,

or membrane fragments containing the channel or transporter of interest

are adsorbed to a lipid monolayer painted over a functionalized

electrode. This electrode consists of a glass support, a chromium layer, a gold layer, and an octadecyl mercaptane

monolayer. Because the painted membrane is supported by the electrode,

it is called a solid-supported membrane. It is important to note that

mechanical perturbations, which usually destroy a biological lipid

membrane, do not influence the life-time of an SSM. The capacitive

electrode (composed of the SSM and the absorbed vesicles) is so

mechanically stable that solutions may be rapidly exchanged at its

surface. This property allows the application of rapid substrate/ligand

concentration jumps to investigate the electrogenic activity of the

protein of interest, measured via capacitive coupling between the

vesicles and the electrode.

Bioelectric recognition assay (BERA)

The

bioelectric recognition assay (BERA) is a novel method for

determination of various chemical and biological molecules by measuring

changes in the membrane potential of cells immobilized in a gel matrix.

Apart from the increased stability of the electrode-cell interface,

immobilization preserves the viability and physiological functions of

the cells. BERA is used primarily in biosensor applications in order to assay analytes that can interact with the immobilized cells

by changing the cell membrane potential. In this way, when a positive

sample is added to the sensor, a characteristic, "signature-like" change

in electrical potential occurs. BERA is the core technology behind the

recently launched pan-European FOODSCAN project, about pesticide and

food risk assessment in Europe. BERA has been used for the detection of human viruses (hepatitis B and C viruses and herpes viruses), veterinary disease agents (foot and mouth disease virus, prions, and blue tongue virus), and plant viruses (tobacco and cucumber viruses)

in a specific, rapid (1–2 minutes), reproducible, and cost-efficient

fashion. The method has also been used for the detection of

environmental toxins, such as pesticides and mycotoxins in food, and 2,4,6-trichloroanisole in cork and wine, as well as the determination of very low concentrations of the superoxide anion in clinical samples.

A BERA sensor has two parts:

- The consumable biorecognition elements

- The electronic read-out device with embedded artificial intelligence.

A recent advance is the development of a technique called molecular

identification through membrane engineering (MIME). This technique

allows for building cells with defined specificity for virtually any

molecule of interest, by embedding thousands of artificial receptors

into the cell membrane.

Computational electrophysiology

While

not strictly constituting an experimental measurement, methods have

been developed to examine the conductive properties of proteins and

biomembranes in silico. These are mainly molecular dynamics simulations in which a model system like a lipid bilayer is subjected to an externally applied voltage. Studies using these setups have been able to study dynamical phenomena like electroporation of membranes and ion translocation by channels.

The benefit of such methods is the high level of detail of the

active conduction mechanism, given by the inherently high resolution and

data density that atomistic simulation affords. There are significant

drawbacks, given by the uncertainty of the legitimacy of the model and

the computational cost of modeling systems that are large enough and

over sufficient timescales to be considered reproducing the macroscopic

properties of the systems themselves. While atomistic simulations may

access timescales close to, or into the microsecond domain, this is

still several orders of magnitude lower than even the resolution of

experimental methods such as patch-clamping.

Clinical electrophysiology

Clinical electrophysiology is the study of how electrophysiological principles and technologies can be applied to human health. For example, clinical cardiac electrophysiology

is the study of the electrical properties which govern heart rhythm and

activity. Cardiac electrophysiology can be used to observe and treat

disorders such as arrhythmia

(irregular heartbeat). For example, a doctor may insert a catheter

containing an electrode into the heart to record the heart muscle's

electrical activity.

Another example of clinical electrophysiology is clinical neurophysiology. In this medical specialty, doctors measure the electrical properties of the brain, spinal cord, and nerves. Scientists such as Duchenne de Boulogne (1806–1875) and Nathaniel A. Buchwald (1924–2006) are considered to have greatly advanced the field of neurophysiology, enabling its clinical applications.

Clinical reporting guidelines

Minimum Information (MI) standards or reporting guidelines specify the minimum amount of meta data

(information) and data required to meet a specific aim or aims in a

clinical study. The "Minimum Information about a Neuroscience

investigation" (MINI) family of reporting guideline documents aims to

provide a consistent set of guidelines in order to report an

electrophysiology experiment. In practice a MINI module comprises a

checklist of information that should be provided (for example about the

protocols employed) when a data set is described for publication.