A chart illustrating the differences in earnings between men and women of the same educational level (USA 2006)

A glass ceiling is a metaphor used to represent an invisible

barrier that keeps a given demographic (typically applied to minorities)

from rising beyond a certain level in a hierarchy.

The metaphor was first coined by feminists in reference to barriers in the careers of high-achieving women. In the US, the concept is sometimes extended to refer to obstacles hindering the advancement of minority women, as well as minority men. Minority women often find the most difficulty in "breaking the glass ceiling" because they lie at the intersection of two historically marginalized groups: women and people of color. East Asian and East Asian American news outlets have coined the term "bamboo ceiling" to refer to the obstacles that all East Asian Americans face in advancing their careers. Similarly, a set of invisible obstacles posed against refugees' efforts to workforce integration is coined "canvas ceiling".

Within the same concepts of the other terms surrounding the

workplace, there are similar terms for restrictions and barriers

concerning women and their roles within organizations and how they

coincide with their maternal duties. These "Invisible Barriers" function

as metaphors to describe the extra circumstances that women undergo,

usually when trying to advance within areas of their careers and often

while trying to advance within their lives outside their work spaces.

"A glass ceiling" represents a barrier that prohibits women from advancing toward the top of a hierarchical corporation.

Women in the workforce are faced with "the glass ceiling." Those

women are prevented from receiving promotion, especially to the

executive rankings, within their corporation. Within the last twenty

years, the women who are becoming more involved and pertinent in

industries and organizations have rarely been in the executive ranks.

Women in most corporations encompass below five percent of board of

directors and corporate officer positions.

Definition

The

United States Federal Glass Ceiling Commission defines the glass

ceiling as "the unseen, yet unbreachable barrier that keeps minorities

and women from rising to the upper rungs of the corporate ladder,

regardless of their qualifications or achievements."

David Cotter and colleagues defined four distinctive characteristics that must be met to conclude that a glass ceiling exists. A glass ceiling inequality represents:

- "A gender or racial difference that is not explained by other job-relevant characteristics of the employee."

- "A gender or racial difference that is greater at higher levels of an outcome than at lower levels of an outcome."

- "A gender or racial inequality in the chances of advancement into higher levels, not merely the proportions of each gender or race currently at those higher levels."

- "A gender or racial inequality that increases over the course of a career."

Cotter and his colleagues found that glass ceilings are correlated

strongly with gender. Both white and minority women face a glass ceiling

in the course of their careers. In contrast, the researchers did not

find evidence of a glass ceiling for African-American men.

The glass ceiling metaphor has often been used to describe

invisible barriers ("glass") through which women can see elite positions

but cannot reach them ("ceiling").

These barriers prevent large numbers of women and ethnic minorities

from obtaining and securing the most powerful, prestigious and

highest-grossing jobs in the workforce.

Moreover, this effect prevents women from filling high-ranking

positions and puts them at a disadvantage as potential candidates for

advancement.

History

In 1839, French feminist and author George Sand used a similar phrase, une voûte de cristal impénétrable, in a passage of Gabriel, a never-performed play: "I was a woman; for suddenly my wings collapsed, ether closed in around my head like an impenetrable crystal vault,

and I fell...." [emphasis added]. The statement, a description of the

heroine's dream of soaring with wings, has been interpreted as a

feminine Icarus tale of a woman who attempts to ascend above her accepted role.

The first person said to use the term Glass ceiling was Marilyn Loden during a 1978 speech.

At the same time, according to the April 3, 2015, Wall Street Journal,

completely independent of Loden, the term glass ceiling was coined in

the spring of 1978 by Marianne Schriber and Katherine Lawrence at

Hewlett-Packard.

The ceiling was defined as discriminatory promotion patterns where the

written promotional policy is non-discriminatory, but in practice denies

promotion to qualified females. Lawrence presented this at the annual

Conference of the Women's Institute for Freedom of the Press at meeting

the National Press.

The term was later used in March 1984 by Gay Bryant. She was the former editor of Working Woman magazine and was changing jobs to be the editor of Family Circle. In an Adweek

article written by Nora Frenkel, Bryant was reported as saying, "Women

have reached a certain point—I call it the glass ceiling. They're in the

top of middle management and they're stopping and getting stuck. There

isn't enough room for all those women at the top. Some are going into

business for themselves. Others are going out and raising families." Also in 1984, Bryant used the term in a chapter of the book The Working Woman Report: Succeeding in Business in the 1980s. In the same book, Basia Hellwig used the term in another chapter.

In a widely cited article in the Wall Street Journal

in March 1986 the term was used in the

article's title: "The Glass Ceiling: Why Women Can't Seem to Break The

Invisible Barrier That Blocks Them From the Top Jobs". The article was

written by Carol Hymowitz and Timothy D. Schellhardt. Hymowitz and

Schellhardt introduced glass ceiling was "not something that could be

found in any corporate manual or even discussed at a business meeting;

it was originally introduced as an invisible, covert, and unspoken

phenomenon that existed to keep executive level leadership positions in

the hands of Caucasian males."

As the term "Glass Ceiling" got more issued within society,

public responded with differing ideas and opinions. Some argued that

glass ceiling is a myth rather than a reality because women chose to

stay home and showed less dedication to advance into executive suite. As a result of continuing public debate, the US Labor Department's chief, Lynn Morley Martin,

reported the results of a research project called "The Glass Ceiling

Initiative" formed to investigate the low numbers of women and

minorities in executive positions. This report defined the new term as

"those artificial barriers based on attitudinal or organizational bias

that prevent qualified individuals from advancing upward in their

organization into management-level positions."

In 1991, as a part of Title II of the Civil Right Act of 1991, Congress created the Glass Ceiling Commission. This 21 member Presidential Commission was chaired by Secretary of Labor Robert Reich,

and was created to study the "barriers to the advancement of minorities

and women within corporate hierarchies (the problem known as the glass

ceiling), to issue a report on its findings and conclusions, and to make

recommendations on ways to dis- mantle the glass ceiling."

The commission conducted extensive research including, surveys, public

hearings and interviews, and released their findings in a report in

1995.

The report, "Good for Business", offered "tangible guidelines and

solutions on how these barriers can be overcome and eliminated".

The goal of the commission was to provide recommendations on how to

shatter the glass ceiling, specifically in the world of business. The

report issued 12 recommendations on how to improve the workplace by

increasing diversity in the organization and reducing discrimination

through policy.

Number of women CEOs from the Fortune Lists has been increasing from 2012–2014,

but ironically women's labor force participation rate decreased from

52.4% to 49.6% between 1995 and 2015 globally. However, it is evident

that some countries like Australia has increased the labor force

participation of women over 27% since 1978. Furthermore, only 19.2% of S&P 500 Board Seats were held by women in 2014, of whom 80.2% were considered white.

Gender pay gap

The gender pay gap is the difference between male and female earnings. In 2008 the OECD

suggested that the median earnings of female full-time workers were 17%

lower than the earnings of their male counterparts and that "30% of the

variation in gender wage gaps across OECD countries can be explained by

discriminatory practices in the labour market." The European Commission suggested that women's hourly earnings were 17.5% lower on average in the 27 EU Member States in 2008.

A paper by political activist website "nationalpartnership.org"

suggests that as of April 2017, women in the United States were on

average paid "80 cents for every dollar paid to men, amounting to an

annual gender wage gap of $10,470".

It may help from a research perspective to note that there are many

disagreeing viewpoints on this issue, and the research cited here is

presented in favor of the side that asserts society's view on minorities

is the cause of the pay gap. Moreover, "based on the human capital

theory, not only the general gender-specific pay differentials, but

also the different proportions of women and men in certain occupations

and fields of work

and thus the gender-specific labor market segregation is explained with

the so-called self selection".

In economics, there are various essential theories that describe the

illegitimate part of the gender pay gap. Gary S. Becker's theory of

"tastes of discrimination" indicates that there are some personal

prejudices which concern cooperation with a certain group of people.

Glass escalator

In addition to the glass ceiling, which already is stopping women

from climbing higher in success in the workplace, a parallel phenomenon

called the "glass escalator"

can be seen to occur. As more men join fields that were previously

dominated by women, such as nursing and teaching, men are promoted and

given more opportunities compared to women, as if men were taking

escalators and women were taking the stairs.

The chart from Carolyn K. Broner shows an example of the glass

escalator in favor of men for female-dominant occupations in schools.

While women have historically dominated the teaching profession, men

tend to take higher positions in school systems such as deans or

principals.

Men benefit financially from their gender status in historically

female field, often "reaping the benefits of their token status to reach

higher levels in female-dominated work."

A 2008 study published in Social Problems

found that sex segregation in nursing did not follow the "glass

escalator" pattern of disproportional vertical distribution; rather, men

and women gravitated towards different areas within the field, with

male nurses tending to specialize in areas of work perceived as

"masculine".

The article noted that "men encounter powerful social pressures that

direct them away from entering female-dominated occupations (Jacobs

1989, 1993)". Since female-dominated occupations are usually

characterized with more feminine activities, men who enter these jobs

can be perceived socially as "effeminate, homosexual, or sexual

predators".

Sticky floor

In

the literature on gender discrimination, the concept of "sticky floors"

complements the concept of a glass ceiling. Sticky floors can be

described as the pattern that women are, compared to men, less likely to

start to climb the job ladder. Thereby, this phenomenon is related to

gender differentials at the bottom of the wage distribution. Building on

the seminal study by Booth and co-authors in European Economic Review,

during the last decade economists have attempted to identify sticky

floors in the labour market. They found empirical evidence for the

existence of sticky floors in countries such as Australia, Belgium,

Italy, Thailand and the United States.

The frozen middle

Similar

to the sticky floor, the frozen middle describes the phenomenon of

women's progress up the corporate ladder slowing, if not halting, in the

ranks of middle management.

Originally the term referred to the resistance corporate upper

management faced from middle management when issuing directives. Due to a

lack of ability or lack of drive in the ranks of middle management

these directives do not come into fruition and as a result the company's

bottom line suffers.The term was popularized by a Harvard Business Review article titled "Middle Management Excellence".

Due to the growing proportion of women to men in the workforce,

however, the term "frozen middle" has become more commonly ascribed to

the aforementioned slowing of the careers of women in middle management.

The 1996 study "A Study of the Career Development and Aspirations of

Women in Middle Management" posits that social structures and networks

within businesses that favor "good old boys" and norms of masculinity

exist based on the experiences of women surveyed.

According to the study, women who did not exhibit stereotypical

masculine traits, (e.g. aggressiveness, thick skin, lack of emotional

expression) and interpersonal communication tendencies are at an

inherent disadvantage compared to their male peers. As the ratio of men to women increases in the upper levels of management,

women's access to female mentors who could advise them on ways to

navigate office politics is limited, further inhibiting upward mobility

within a corporation or firm.

Furthermore, the frozen middle affects female professionals in western

and eastern countries such as the United States and Malaysia,

respectively, as well as women in a variety of fields ranging from the aforementioned corporations to STEM fields.

Glass Ceiling Index

In 2017, the Economist

updated their glass-ceiling index. It combines data on higher

education, labour-force participation, pay, child-care costs, maternity

and paternity rights, business-school applications and representation in

senior jobs. The countries where inequality was the lowest were, in order of most equality, Iceland, Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Poland.

Gender stereotypes

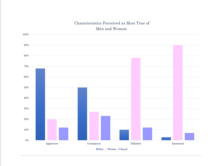

Gallup Poll: Men are more Aggressive, Women are more Emotional

In a 1993 report released through the U.S. Army Research Institute

for the Behavioral and Social Sciences, researchers noted that women

have the same educational opportunities as their male counterparts, the

Glass Ceiling persist due to systematic barriers, low representation and

mobility, and stereotypes.

Feminine stereotypes attributed to women is one widely recognized

reason as to why female employees are systematically inhibited from

receiving advantageous opportunities in their career field. A majority of Americans perceive women to be more emotional and men to be more aggressive than their opposite sex.

Gender stereotypes influence how leaders are chosen by employers and

how workers of different sex are treated. Glass ceilings can be observed

in the typical American supermarket in which women are assigned to be

cashiers due to the belief that women are better than their male

co-workers at emotional management with customers. Journeyman clerks

whom are mostly assigned cashier shifts experience a low quality of work

and significantly less promotions.

A class action lawsuit was filed against Lucky Stores for the unjust

assignment of tasks to employees of different race and sex.

Moreover, one of the stereotypes towards women in workplaces is "gender

status belief" which claims that men are more competent and intelligent

than women, thus they have much higher positions in the career

hierarchy. Ultimately, this factor leads to perception of gender-based

jobs on the labor market, so men are expected to have more work-related

qualifications and hired for top positions.Glass Ceiling Effect and Earnings - The Gender Pay Gap in Managerial Positions in Germany. Perceived feminine stereotypes contribute to the glass ceiling faced by women in the workforce.

Types of women facing the glass ceiling in the workplace

"Intentional

Entrepreneurs" illustrate women who are involved in their workforce and

intentionally engage in the culture and operations of the particular

workplace in order to triumph to entrepreneurial levels. (Miree)

"Corporate Climbers" are the result of deliberately or

unintentionally being forced out of a corporation. They hit "the glass

ceiling" of their previous business; thus, those women start their own.

"The intentional entrepreneurs" and "the corporate climbers"

focus on the women who are competing for entrepreneurial positions

against the men. Men who uphold the desire and determination for

entrepreneurial positions are normally competing against other men,

while women feel inclined to find ethical and logical reasons to

enlighten corporate America or the particular workplace for why they are

equally as qualified. Women are forced out of Corporate America,

essentially reaching "the glass ceiling," women corporate climbers do

not have another alternative other than starting their own business.

Hiring practices

When

women leave their current business to start their own, they tend to

hire other women. Men tend to hire other men. These hiring practices

eliminate "the glass ceiling" because there is no more competition of

capabilities and discrimination of gender. These support the segregated

identification of "men’s work" and "women’s work."

Second shift

The

second shift focuses on the idea that women theoretically work a second

shift in the manner of having a greater workload, not just doing a

greater share of domestic work. All of the tasks that are engaged in

outside the workplace are mainly tied to motherhood. Depending on

location, household income, educational attainment, ethnicity and

location. Data shows that women do work a second shift in the sense of

having a greater workload, not just doing a greater share of domestic

work, but this is not apparent if simultaneous activity is overlooked. Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein

as early as 1956 focused on the potential of both men and women working

in settings that included paid and unpaid types of work environments.

Research indicated that men and women could have equal time for

activities outside the work environment for family and extra activities.

This "second shift" has also been found to have physical effects as

well, especially for women. Women whom engage in longer hours in pursuit

of family balance, often suffer more mental health issues such as

depression, anxiety, and other problems. Irritability, low motivation

and energy, and other emotional issues have been found as well. The

overall happiness of women can be improved if the balance of career and

home responsibilities are met.

Mommy Track

"Mommy

Track" refers to women who simply disregard their career and

professional duties in order to satisfy the needs of their families.

Women are often subject to long work hours that creates an imbalance

within the work-family schedule.

There is research suggesting that women were able to function on a

part-time professional schedule compared to others who worked full-time

while still engaged in external family activities. The research also

suggests flexible work arrangements allow for the achievement of a

healthy work and family balance. A difference has also been discovered

in the cost and amount of effort in childbearing amongst women in higher

skilled positions and roles, as opposed to women in lower-skilled jobs.

This difference leads to women delaying and postponing goals and career

aspirations over a number of years. A large number of women across the

country who have vocational/professional certifications and degrees have

been found to be not a part of the working force at the estimated rate

more than twice times as male counterparts. Also, the Deloitte Touche,

a professional hiring service firm, confirmed that they had recorded

dropout rates in each entering class of hires and reported that indeed

women's rates were very high compared to males due to mother- and

family-related responsibilities.

Concrete floor

The term concrete floor

has been used to refer to the minimum number or the proportion of women

necessary for a cabinet or board of directors to be perceived as

legitimate.

Cross-cultural context

Few

women tend to reach positions in upper echelon and organizations are

largely still almost exclusively lead by men. Studies have shown that

the glass ceiling still exists in varying levels in different nations

and regions across the world.

The stereotypes of women as emotional and sensitive could be seen as

key characteristics as to why women struggle to break the glass ceiling.

It is clear that even though societies differ from one another by

culture, beliefs and norms, they hold similar expectations of women and

their role in the society. These female stereotypes are often reinforced

in societies that have traditional expectations of women.

The stereotypes and perceptions of women are changing slowly across the

world, which also reduces gender segregation in organizations.