1920 Bolshevik Party meeting: sitting (from left) are Enukidze, Kalinin, Bukharin, Tomsky, Lashevich, Kamenev, Preobrazhensky, Serebryakov, Lenin and Rykov

The Bolsheviks, also known in English as the Bolshevists, were a radical far-left Marxist faction founded by Vladimir Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov that split from the Menshevik faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), a revolutionary socialist political party formed in 1898, at its Second Party Congress in 1903.

After forming their own party in 1912, the Bolsheviks took power in Russia in November 1917, overthrowing the liberal Provisional Government of Alexander Kerensky, and became the only ruling party in the subsequent Soviet Russia and its successor state, the Soviet Union. They considered themselves the leaders of the revolutionary working class of Russia. Their beliefs and practices were often referred to as Bolshevism.

History of the split

Lenin's ideology in What Is to Be Done?

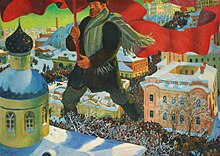

Bolshevik, Boris Kustodiev, 1920

Lenin's political pamphlet What Is to Be Done?,

which Lenin wrote in 1901 and published in 1902, helped to precipitate

the split. In Germany, the book was published in 1902; but in Russia,

strict censorship outlawed its publication and distribution.

One of the main points of Lenin's writing was that a revolution can

only be achieved by the strong leadership of the masses by one person,

or by a very select few, who would dedicate their entire lives to the

cause, although after the proposed revolution had successfully

overthrown the government, this strong leadership would relinquish power

to allow socialism to fully develop. Lenin said that if professional

revolutionaries did not maintain control over the workers, then they

would lose sight of the party's objective and adopt opposing beliefs,

even abandon the revolution entirely.

The pamphlet also showed that Lenin's view of a socialist intelligentsia

was not in line with Marxist theory, which also created some party

unrest. For example, Lenin agreed with the Marxist idea of eliminating

social classes, but his vision of a future society encompassed visible

distinctions between those in politics and the common worker. Most party

members considered unequal treatment of workers immoral and were loyal

to the idea of a completely classless society.

This pamphlet also showed that Lenin opposed another group of

reformers, known as "Economists", who were for economic reform while

leaving the government relatively unchanged and who, in Lenin's view,

failed to recognize the importance of uniting the working population

behind the party's cause.

2nd party congress

At the 2nd Congress of the RSDLP, which was held in Brussels and then London during August 1903, Lenin and Julius Martov

disagreed over the party membership rules. Lenin, who was supported by

Plekhanov, wanted to limit membership to those who supported the party

full-time and worked in complete obedience to the elected party

leadership. Martov wanted to extend membership to anyone "who recognises

the Party Programme and supports it by material means and by regular

personal assistance under the direction of one of the party’s

organisations". Lenin believed his plan would develop a core group of professional revolutionaries who would devote their full time and energy towards developing the party into an organization capable of leading a successful workers' revolution against the Tsarist autocracy.

The base of active and experienced members would be the

recruiting ground for this professional core. Sympathizers would be left

outside and the party would be organised based on the concept of democratic centralism.

Martov, until then a close friend of Lenin, agreed with him that the

core of the party should consist of professional revolutionaries, but he

argued that party membership should be open to sympathizers,

revolutionary workers, and other fellow travellers. The two had

disagreed on the issue as early as March–May 1903, but it was not until

the Congress that their differences became irreconcilable and split the

party.

At first, the disagreement appeared to be minor and inspired by

personal conflicts. For example, Lenin's insistence on dropping less

active editorial board members from Iskra

or Martov's support for the Organizing Committee of the Congress which

Lenin opposed. The differences grew and the split became irreparable.

Internal unrest also arose over the political structure that was best suited for Soviet power. As discussed in What Is To Be Done?,

Lenin firmly believed that a rigid political structure was needed to

effectively initiate a formal revolution. This idea was met with

opposition from once close followers, including Martov, Georgy

Plekhanov, Leon Trotsky, and Pavel Axelrod.

Plekhanov and Lenin's major dispute arose addressing the topic of

nationalizing land or leaving it for private use. Lenin wanted to

nationalize to aid in collectivization whereas Plekhanov thought worker

motivation would remain higher if individuals were able to maintain

their own property. Those who opposed Lenin and wanted to continue on

the Marxist path towards complete socialism and disagreed with his

strict party membership guidelines became known as "softs" while Lenin

supporters became known as "hards".

Some of the factionalism could be attributed to Lenin's steadfast

belief in his own opinion and what was described by Plekhanov as

Lenin's inability to "bear opinions which were contrary to his own"

and loyalty to his own self-envisioned utopia. Lenin was seen even by

fellow party members as being so narrow-minded and unable to accept

criticism that he believed that anyone who didn't follow him was his

enemy. Leon Trotsky, one of Lenin's fellow revolutionaries, compared Lenin in 1904 to the French revolutionary Maximilien Robespierre.

Origins of Bolshevik and Menshevik

The

two factions were originally known as "hard" (Lenin's supporters) and

"soft" (Martov's supporters), but the terminology soon changed to

"Bolsheviks" and "Mensheviks", from the Russian bolshinstvo ("majority") and menshinstvo ("minority"). In the Second Party Congress vote, the Bolsheviks won votes on the majority of important issues, hence the name.

On the other hand, Martov's supporters won the vote concerning the

question of party membership. Neither Lenin nor Martov had a firm

majority throughout the Congress as delegates left or switched sides. In

the end, the Congress was evenly split between the two factions.

From 1907 on, English language articles sometimes used the term

"Maximalist" for "Bolshevik" and "Minimalist" for "Menshevik", which

proved confusing since there was also a "Maximalist" faction within the

Russian Socialist Revolutionary Party in 1904–1906 (which after 1906 formed a separate Union of Socialists-Revolutionaries Maximalists) and then again after 1917.

The Bolsheviks ultimately became the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The Bolsheviks, or Reds, came to power in Russia during the October Revolution phase of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and founded the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR). With the Reds defeating the Whites and others during the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922, the RSFSR became the chief constituent of the Soviet Union (USSR) in December 1922.

Demographics of the two factions

The

average party member was very young. In 1907, 22% of Bolsheviks were

under 20, 37% were 20–24 and 16% were 25–29. By 1905, 62% of the members

were industrial workers (3% of the population in 1897).

22% of Bolsheviks were gentry (1.7% of the total population), 38% were

uprooted peasants, compared with 19% and 26% for the Mensheviks. In

1907, 78.3% of the Bolsheviks were Russian and 10% were Jewish (34% and

20% for the Mensheviks). Total membership was 8,400 in 1905, 13,000 in

1906 and 46,100 by 1907 (8,400, 18,000 and 38,200 for the Mensheviks).

By 1910, both factions together had fewer than 100,000 members.

Beginning of the 1905 Revolution (1903–1905)

The two factions were in a state of flux in 1903–1904 with many members changing sides. The founder of Russian Marxism, Georgy Plekhanov,

who at first allied himself with Lenin and the Bolsheviks, had parted

ways with them by 1904. Trotsky at first supported the Mensheviks, but

he left them in September 1904 over their insistence on an alliance with

Russian liberals and their opposition to a reconciliation with Lenin

and the Bolsheviks. He remained a self-described "non-factional social

democrat"

until August 1917, when he joined Lenin and the Bolsheviks, as their

positions resembled his and he came to believe that Lenin was right on

the issue of the party.

All but one member of the RSDLP Central Committee were arrested in Moscow in early 1905. The remaining member, with the power of appointing a new committee, was won over by the Bolsheviks.

The lines between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks hardened in

April 1905 when the Bolsheviks held a Bolsheviks-only meeting in London,

which they called the 3rd Party Congress. The Mensheviks organised a

rival conference and the split was thus finalized.

The Bolsheviks played a relatively minor role in the 1905 Revolution and were a minority in the Saint Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Deputies led by Trotsky. However, the less significant Moscow Soviet was dominated by the Bolsheviks. These Soviets became the model for those formed in 1917.

Mensheviks (1906–1907)

As the Russian Revolution of 1905 progressed, Bolsheviks, Mensheviks,

and smaller non-Russian social democratic parties operating within the

Russian Empire attempted to reunify at the 4th (Unification) Congress of the RSDLP held in April 1906 at Folkets hus, Norra Bantorget, in Stockholm. When the Mensheviks made an alliance with the Jewish Bund, the Bolsheviks found themselves in a minority.

However, all factions retained their respective factional structure and the Bolsheviks formed the Bolshevik Centre, the de facto

governing body of the Bolshevik faction within the RSDLP. At the Fifth

Congress held in London in May 1907, the Bolsheviks were in the

majority, but the two factions continued functioning mostly

independently of each other.

Split between Lenin and Bogdanov (1908–1910)

Tensions had existed between Lenin and Alexander Bogdanov from as early as 1904. Lenin had fallen out with Nikolai Valentinov after Valentinov had introduced him to Ernst Mach's

Empiriocriticism, a viewpoint that Bogdanov had been exploring and

developing as Empiriomonism. Having worked as co-editor with Plekhanov

on Zarya, Lenin had come to agree with the Valentinov's rejection of Bogdanov's Empiriomonism.

With the defeat of the revolution in mid-1907 and the adoption of a

new, highly restrictive election law, the Bolsheviks began debating

whether to boycott the new parliament known as the Third Duma. Lenin, Grigory Zinoviev, Lev Kamenev, and others argued for participating in the Duma while Bogdanov, Anatoly Lunacharsky, Mikhail Pokrovsky, and others argued that the social democratic faction in the Duma should be recalled. The latter became known as "recallists" (otzovists

in Russian). A smaller group within the Bolshevik faction demanded that

the RSDLP central committee should give its sometimes unruly Duma

faction an ultimatum, demanding complete subordination to all party

decisions. This group became known as "ultimatists" and was generally allied with the recallists.

With most Bolshevik leaders either supporting Bogdanov or

undecided by mid-1908 when the differences became irreconcilable, Lenin

concentrated on undermining Bogdanov's reputation as a philosopher. In

1909, he published a scathing book of criticism entitled Materialism and Empirio-criticism (1909), assaulting Bogdanov's position and accusing him of philosophical idealism. In June 1909, Bogdanov proposed the formation of Party Schools as Proletarian Universities at a Bolshevik mini-conference in Paris organised by the editorial board of the Bolshevik magazine Proletary. However, this proposal was not adopted and Lenin tried to expel Bogdanov from the Bolshevik faction. Bogdanov was then involved with setting up Vpered, which ran the Capri Party School from August to December 1909.

Final attempt at party unity (1910)

With both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks weakened by splits within their ranks and by Tsarist

repression, the two factions were tempted to try to re-unite the party.

In January 1910, Leninists, recallists, and various Menshevik factions

held a meeting of the party's Central Committee in Paris. Kamenev and

Zinoviev were dubious about the idea; but under pressure from

conciliatory Bolsheviks like Victor Nogin, they were willing to give it a try.

One of the underlying reasons that prevented any reunification of

the party was the Russian police. The police were able to infiltrate

both parties' inner circles by sending in spies who then reported on the

opposing party's intentions and hostilities. This allowed the tensions to remain high between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks and helped prevent their uniting.

Lenin was firmly opposed to any re-unification but was outvoted

within the Bolshevik leadership. The meeting reached a tentative

agreement, and one of its provisions was to make Trotsky's Vienna-based Pravda

a party-financed central organ. Kamenev, Trotsky's brother-in-law who

was with the Bolsheviks, was added to the editorial board; but the

unification attempts failed in August 1910 when Kamenev resigned from

the board amid mutual recriminations.

Forming a separate party (1912)

The factions permanently broke relations in January 1912 after the Bolsheviks organised a Bolsheviks-only Prague Party Conference

and formally expelled Mensheviks and recallists from the party. As a

result, they ceased to be a faction in the RSDLP and instead declared

themselves an independent party, called Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) – or RSDLP(b). Unofficially, the party has been referred to as the Bolshevik Party. Throughout the 20th century, the party adopted a number of different names. In 1918, RSDLP(b) became All-Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and remained so until 1925. From 1925–1952, the name was All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and from 1952–1991 Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

As the party split became permanent, further divisions became

evident. One of the most notable differences was how each faction

decided to fund its revolution. The Mensheviks decided to fund their

revolution through membership dues while Lenin often resorted to more

drastic measures since he required a higher budget.

One of the common methods the Bolsheviks used was committing bank

robberies, one of which, in 1907, resulted in the party getting over

250,000 roubles, which is the equivalent of about $125,000.

Bolsheviks were in constant need of money because Lenin practised his

beliefs, expressed in his writings, that revolutions must be led by

individuals who devote their entire lives to the cause. As compensation,

he rewarded them with salaries for their sacrifice and dedication. This

measure was taken to help ensure that the revolutionaries stayed

focused on their duties and motivated them to perform their jobs. Lenin

also used the party money to print and copy pamphlets which were

distributed in cities and at political rallies in an attempt to expand

their operations. Both factions received funds through donations from

wealthy supporters.

The elections to the Russian Constituent Assembly

took place in November 1917 in which the Bolsheviks came second with

23.9% of the vote and dissolved the Assembly in January 1918

Further differences in party agendas became evident as the beginning of World War I loomed near. Joseph Stalin was especially eager for the start of the war, hoping that it would turn into a war between classes or essentially a Russian Civil War.

This desire for war was fuelled by Lenin's vision that the workers and

peasants would resist joining the war effort and therefore be more

compelled to join the socialist movement. Through the increase in

support, Russia would then be forced to withdraw from the Allied powers

in order to resolve her internal conflict. Unfortunately for the

Bolsheviks, Lenin's assumptions were incorrect. Despite his and the

party's attempts to push for a civil war through involvement in two

conferences in 1915 and 1916 in Switzerland, the Bolsheviks were in the

minority in calling for a ceasefire by the Russian Army in World War I.

Although the Bolshevik leadership had decided to form a separate

party, convincing pro-Bolshevik workers within Russia to follow suit

proved difficult. When the first meeting of the Fourth Duma was convened

in late 1912, only one out of six Bolshevik deputies, Matvei Muranov (another one, Roman Malinovsky, was later exposed as an Okhrana agent), voted on 15 December 1912 to break from the Menshevik faction within the Duma. The Bolshevik leadership eventually prevailed, and the Bolsheviks formed their own Duma faction in September 1913.

One final difference between the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks was

how ferocious and tenacious the Bolshevik party was in order to achieve

its goals, although Lenin was open minded to retreating from political

ideals if he saw the guarantee of long-term gains benefiting the party.

This practice was seen in the party's trying to recruit peasants and

uneducated workers by promising them how glorious life would be after

the revolution and granting them temporary concessions.

In 1918, the party renamed itself the Russian Communist Party

(Bolsheviks) at Lenin's suggestion. In 1925, this was changed to

All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks). At the 19th Party Congress in 1952 the Bolshevik Party was renamed the Communist Party of the Soviet Union at Stalin's suggestion.

Non-Russian/Soviet groups having used the name "Bolshevik"

- Bangladesh: Maoist Bolshevik Reorganisation Movement of the Purba Banglar Sarbahara Party

- Burkina Faso: Burkinabé Bolshevik Party

- India: Bolshevik Party of India

- India/Sri Lanka: Bolshevik-Leninist Party of India, Ceylon and Burma

- India: Revolutionary Socialist Party (Bolshevik)

- Mexico: Bolshevik Communist Party

- Senegal: Bolshevik Nuclei

- Sri Lanka: Bolshevik Samasamaja Party

- Turkey: Bolshevik Party (North Kurdistan – Turkey)

Derogatory usage of "Bolshevik"

"Down with Bolshevism. Bolshevism brings war and destruction, hunger and death", anti-Bolshevik German propaganda, 1919

"Bolo" was a derogatory expression for Bolsheviks used by British service personnel in the North Russian Expeditionary Force which intervened against the Red Army during the Russian Civil War. Adolf Hitler, Joseph Goebbels and other Nazi leaders used it in reference to the worldwide political movement coordinated by the Comintern. During the days of the Cold War

in the United Kingdom, labour union leaders and other leftists were

sometimes derisively described as "Bolshies". The usage is roughly

equivalent to the term "commie", "Red", or "pinko"

in the United States during the same period. The term "Bolshie" later

became a slang term for anyone who was rebellious, aggressive, or

truculent.