Food preservation prevents the growth of microorganisms (such as yeasts), or other microorganisms (although some methods work by introducing benign bacteria or fungi to the food), as well as slowing the oxidation of fats that cause rancidity. Food preservation may also include processes that inhibit visual deterioration, such as the enzymatic browning reaction in apples after they are cut during food preparation.

Many processes designed to preserve food involve more than one food preservation method. Preserving fruit by turning it into jam, for example, involves boiling (to reduce the fruit's moisture content and to kill bacteria, etc.), sugaring (to prevent their re-growth) and sealing within an airtight jar (to prevent recontamination). Some traditional methods of preserving food have been shown to have a lower energy input and carbon footprint, when compared to modern methods.

Some methods of food preservation are known to create carcinogens. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization classified processed meat, i.e. meat that has undergone salting, curing, fermenting, and smoking, as "carcinogenic to humans".

Maintaining or creating nutritional value, texture and flavor is an important aspect of food preservation.

Many processes designed to preserve food involve more than one food preservation method. Preserving fruit by turning it into jam, for example, involves boiling (to reduce the fruit's moisture content and to kill bacteria, etc.), sugaring (to prevent their re-growth) and sealing within an airtight jar (to prevent recontamination). Some traditional methods of preserving food have been shown to have a lower energy input and carbon footprint, when compared to modern methods.

Some methods of food preservation are known to create carcinogens. In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer of the World Health Organization classified processed meat, i.e. meat that has undergone salting, curing, fermenting, and smoking, as "carcinogenic to humans".

Maintaining or creating nutritional value, texture and flavor is an important aspect of food preservation.

Traditional techniques

New techniques of food preservation became available to the home chef from the dawn of agriculture until the Industrial Revolution.Curing

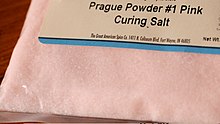

Bag of Prague powder#1, also known as "curing salt"

or "pink salt". It is typically a combination of salt and sodium

nitrite, with the pink color added to distinguish it from ordinary salt.

The earliest form of curing was dehydration or drying, used as early as 12,000 BC. Smoking and salting

techniques improve on the drying process and add antimicrobial agents

that aid in preservation. Smoke deposits a number of pyrolysis products

onto the food, including the phenols syringol, guaiacol and catechol. Salt accelerates the drying process using osmosis and also inhibits the growth of several common strains of bacteria. More recently nitrites have been used to cure meat, contributing a characteristic pink colour.

Cooling

Cooling

preserves food by slowing down the growth and reproduction of

microorganisms and the action of enzymes that causes the food to rot.

The introduction of commercial and domestic refrigerators drastically

improved the diets of many in the Western world

by allowing food such as fresh fruit, salads and dairy products to be

stored safely for longer periods, particularly during warm weather.

Before the era of mechanical refrigeration, cooling for food storage occurred in the forms of root cellars and iceboxes. Rural people often did their own ice cutting, whereas town and city dwellers often relied on the ice trade. Today, root cellaring remains popular among people who value various goals, including local food, heirloom crops, traditional home cooking techniques, family farming, frugality, self-sufficiency, organic farming, and others.

Freezing

Freezing

is also one of the most commonly used processes, both commercially and

domestically, for preserving a very wide range of foods, including

prepared foods that would not have required freezing in their unprepared

state. For example, potato waffles are stored in the freezer, but

potatoes themselves require only a cool dark place to ensure many

months' storage. Cold stores provide large-volume, long-term storage for

strategic food stocks held in case of national emergency in many

countries.

Boiling

Boiling liquid food items can kill any existing microbes. Milk and

water are often boiled to kill any harmful microbes that may be present

in them.

Heating

Heating to temperatures which are sufficient to kill microorganisms inside the food is a method used with perpetual stews. Milk is also boiled before storing to kill many microorganisms.

Sugaring

The earliest cultures have used sugar as a preservative, and it was commonplace to store fruit in honey. Similar to pickled foods, sugar cane was brought to Europe through the trade routes. In northern climates without sufficient sun to dry foods, preserves are made by heating the fruit with sugar.

"Sugar tends to draw water from the microbes (plasmolysis). This

process leaves the microbial cells dehydrated, thus killing them. In

this way, the food will remain safe from microbial spoilage." Sugar is used to preserve fruits, either in an antimicrobial syrup with fruit such as apples, pears, peaches, apricots, and plums,

or in crystallized form where the preserved material is cooked in sugar

to the point of crystallization and the resultant product is then

stored dry. This method is used for the skins of citrus fruit (candied peel), angelica, and ginger. Also, sugaring can be used in the production of jam and jelly.

Pickling

Pickling is a method of preserving food in an edible, antimicrobial

liquid. Pickling can be broadly classified into two categories: chemical

pickling and fermentation pickling.

In chemical pickling, the food is placed in an edible liquid that

inhibits or kills bacteria and other microorganisms. Typical pickling

agents include brine (high in salt), vinegar, alcohol, and vegetable oil.

Many chemical pickling processes also involve heating or boiling so

that the food being preserved becomes saturated with the pickling agent.

Common chemically pickled foods include cucumbers, peppers, corned beef, herring, and eggs, as well as mixed vegetables such as piccalilli.

In fermentation pickling, bacteria in the liquid produce organic acids as preservation agents, typically by a process that produces lactic acid through the presence of lactobacillales. Fermented pickles include sauerkraut, nukazuke, kimchi, and surströmming.

Lye

Sodium hydroxide (lye) makes food too alkaline for bacterial growth. Lye will saponify fats in the food, which will change its flavor and texture. Lutefisk uses lye in its preparation, as do some olive recipes. Modern recipes for century eggs also call for lye.

Canning

Preserved food

Canning involves cooking food, sealing it in sterilized cans or jars, and boiling the containers to kill or weaken any remaining bacteria as a form of sterilization. It was invented by the French confectioner Nicolas Appert.

By 1806, this process was used by the French Navy to preserve meat,

fruit, vegetables, and even milk. Although Appert had discovered a new

way of preservation, it wasn't understood until 1864 when Louis Pasteur found the relationship between microorganisms, food spoilage, and illness.

Foods have varying degrees of natural protection against spoilage and may require that the final step occur in a pressure cooker. High-acid fruits like strawberries require no preservatives to can and only a short boiling cycle, whereas marginal vegetables such as carrots

require longer boiling and addition of other acidic elements. Low-acid

foods, such as vegetables and meats, require pressure canning. Food

preserved by canning or bottling is at immediate risk of spoilage once

the can or bottle has been opened.

Lack of quality control in the canning process may allow ingress

of water or micro-organisms. Most such failures are rapidly detected as

decomposition within the can causes gas production and the can will

swell or burst. However, there have been examples of poor manufacture

(underprocessing) and poor hygiene allowing contamination of canned food by the obligate anaerobe Clostridium botulinum,

which produces an acute toxin within the food, leading to severe

illness or death. This organism produces no gas or obvious taste and

remains undetected by taste or smell. Its toxin is denatured by cooking,

however. Cooked mushrooms, handled poorly and then canned, can support the growth of Staphylococcus aureus, which produces a toxin that is not destroyed by canning or subsequent reheating.

Jellying

Food may be preserved by cooking in a material that solidifies to form a gel. Such materials include gelatin, agar, maize flour, and arrowroot flour. Some foods naturally form a protein gel when cooked, such as eels and elvers, and sipunculid worms, which are a delicacy in Xiamen, in the Fujian province of the People's Republic of China. Jellied eels are a delicacy in the East End of London, where they are eaten with mashed potatoes. Potted meats in aspic (a gel made from gelatin and clarified meat broth) were a common way of serving meat off-cuts in the UK until the 1950s. Many jugged meats are also jellied. A traditional British way of preserving meat (particularly shrimp)

is by setting it in a pot and sealing it with a layer of fat. Also

common is potted chicken liver; jellying is one of the steps in

producing traditional pâtés.

Besides jellying of meat and seafood, a widely known type of

Jellying is fruit preserves which are preparations of fruits, vegetables

and sugar, often stored in glass jam jars and Mason jars. Many

varieties of fruit preserves are made globally, including sweet fruit

preserves, such as those made from strawberry or apricot, and savory

preserves, such as those made from tomatoes or squash. The ingredients

used and how they are prepared determine the type of preserves; jams,

jellies, and marmalades are all examples of different styles of fruit

preserves that vary based upon the fruit used. In English, the word, in

plural form, "preserves" is used to describe all types of jams and

jellies.

Jugging

Meat can be preserved by jugging. Jugging is the process of stewing the meat (commonly game or fish) in a covered earthenware jug or casserole. The animal to be jugged is usually cut into pieces, placed into a tightly-sealed jug with brine or gravy, and stewed. Red wine

and/or the animal's own blood is sometimes added to the cooking liquid.

Jugging was a popular method of preserving meat up until the middle of

the 20th century.

Burial

Burial of food can preserve it due to a variety of factors: lack of light, lack of oxygen, cool temperatures, pH level, or desiccants

in the soil. Burial may be combined with other methods such as salting

or fermentation. Most foods can be preserved in soil that is very dry

and salty (thus a desiccant) such as sand, or soil that is frozen.

Many root vegetables

are very resistant to spoilage and require no other preservation than

storage in cool dark conditions, for example by burial in the ground,

such as in a storage clamp. Century eggs

are traditionally created by placing eggs in alkaline mud (or other

alkaline substance), resulting in their "inorganic" fermentation through

raised pH instead of spoiling. The fermentation preserves them and

breaks down some of the complex, less flavorful proteins and fats into

simpler, more flavorful ones. Cabbage was traditionally buried during Autumn in northern US farms for preservation. Some methods keep it crispy while other methods produce sauerkraut. A similar process is used in the traditional production of kimchi.

Sometimes meat is buried under conditions that cause preservation. If

buried on hot coals or ashes, the heat can kill pathogens, the dry ash

can desiccate, and the earth can block oxygen and further contamination.

If buried where the earth is very cold, the earth acts like a

refrigerator.

In Orissa, India,

it is practical to store rice by burying it underground. This method

helps to store for three to six months during the dry season.

Butter and similar substances have been preserved as bog butter in Irish peat bogs for centuries.

Confit

Meat can be preserved by salting it, cooking it at or near 100 °C in some kind of fat (such as lard or tallow),

and then storing it immersed in the fat. These preparations were

popular in Europe before refrigerators became ubiquitous. They are

still popular in France, where they are called confit. The preparation will keep longer if stored in a cold cellar or buried in cold ground.

Fermentation

Some foods, such as many cheeses, wines, and beers,

use specific micro-organisms that combat spoilage from other

less-benign organisms. These micro-organisms keep pathogens in check by

creating an environment toxic for themselves and other micro-organisms

by producing acid or alcohol. Methods of fermentation include, but are

not limited to, starter micro-organisms, salt, hops, controlled (usually

cool) temperatures and controlled (usually low) levels of oxygen. These

methods are used to create the specific controlled conditions that will

support the desirable organisms that produce food fit for human

consumption.

Fermentation is the microbial conversion of starch and sugars

into alcohol. Not only can fermentation produce alcohol, but it can also

be a valuable preservation technique. Fermentation can also make foods

more nutritious and palatable. For example, drinking water in the Middle

Ages was dangerous because it often contained pathogens that could

spread disease. When the water is made into beer, the boiling during the

brewing process kills any bacteria in the water that could make people

sick. Additionally, the water now has the nutrients from the barley and

other ingredients, and the microorganisms can also produce vitamins as

they ferment.

Modern industrial techniques

Techniques of food preservation were developed in research laboratories for commercial applications.

Pasteurization

Pasteurization is a process for preservation of liquid food. It was

originally applied to combat the souring of young local wines. Today,

the process is mainly applied to dairy products. In this method, milk is

heated at about 70 °C (158 °F) for 15–30 seconds to kill the bacteria

present in it and cooling it quickly to 10 °C (50 °F) to prevent the

remaining bacteria from growing. The milk is then stored in sterilized

bottles or pouches in cold places. This method was invented by Louis Pasteur, a French chemist, in 1862.

Vacuum packing

Vacuum-packing stores food in a vacuum environment, usually in an air-tight bag or bottle. The vacuum environment strips bacteria of oxygen needed for survival. Vacuum-packing is commonly used for storing nuts

to reduce loss of flavor from oxidization. A major drawback to vacuum

packaging, at the consumer level, is that vacuum sealing can deform

contents and rob certain foods, such as cheese, of its flavor.

Artificial food additives

Preservative food additives can be antimicrobial—which inhibit the growth of bacteria or fungi, including mold—or antioxidant, such as oxygen absorbers, which inhibit the oxidation of food constituents. Common antimicrobial preservatives include calcium propionate, sodium nitrate, sodium nitrite, sulfites (sulfur dioxide, sodium bisulfite, potassium hydrogen sulfite, etc.), and EDTA. Antioxidants include butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) and butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). Other preservatives include formaldehyde (usually in solution), glutaraldehyde (insecticide), ethanol, and methylchloroisothiazolinone.

Irradiation

Irradiation of food is the exposure of food to ionizing radiation. Multiple types of ionizing radiation can be used, including beta particles (high-energy electrons) and gamma rays (emitted from radioactive sources such as cobalt-60 or cesium-137).

Irradiation can kill bacteria, molds, and insect pests, reduce the

ripening and spoiling of fruits, and at higher doses induce sterility.

The technology may be compared to pasteurization;

it is sometimes called "cold pasteurization", as the product is not

heated. Irradiation may allow lower-quality or contaminated foods to be

rendered marketable.

National and international expert bodies have declared food irradiation as "wholesome"; organizations of the United Nations, such as the World Health Organization and Food and Agriculture Organization, endorse food irradiation. Consumers may have a negative view of irradiated food based on the misconception that such food is radioactive;

in fact, irradiated food does not and cannot become radioactive.

Activists have also opposed food irradiation for other reasons, for

example, arguing that irradiation can be used to sterilize contaminated

food without resolving the underlying cause of the contamination. International legislation on whether food may be irradiated or not varies worldwide from no regulation to a full ban.

Approximately 500,000 tons of food items are irradiated per year worldwide in over 40 countries. These are mainly spices and condiments, with an increasing segment of fresh fruit irradiated for fruit fly quarantine.

Pulsed electric field electroporation

Pulsed electric field (PEF) electroporation is a method for

processing cells by means of brief pulses of a strong electric field.

PEF holds potential as a type of low-temperature alternative

pasteurization process for sterilizing food products. In PEF processing,

a substance is placed between two electrodes, then the pulsed electric

field is applied. The electric field enlarges the pores of the cell

membranes, which kills the cells and releases their contents. PEF for

food processing is a developing technology still being researched. There

have been limited industrial applications of PEF processing for the

pasteurization of fruit juices. To date, several PEF treated juices are

available on the market in Europe. Furthermore, for several years a

juice pasteurization application in the US has used PEF. For cell

disintegration purposes especially potato processors show great interest

in PEF technology as an efficient alternative for their preheaters.

Potato applications are already operational in the US and Canada. There

are also commercial PEF potato applications in various countries in

Europe, as well as in Australia, India, and China.

Modified atmosphere

Modifying atmosphere is a way to preserve food by operating on the

atmosphere around it. Salad crops that are notoriously difficult to

preserve are now being packaged in sealed bags with an atmosphere

modified to reduce the oxygen (O2) concentration and increase the carbon dioxide (CO2)

concentration. There is concern that, although salad vegetables retain

their appearance and texture in such conditions, this method of

preservation may not retain nutrients, especially vitamins.

There are two methods for preserving grains with carbon dioxide. One method is placing a block of dry ice

in the bottom and filling the can with the grain. Another method is

purging the container from the bottom by gaseous carbon dioxide from a

cylinder or bulk supply vessel.

Carbon dioxide prevents insects and, depending on concentration, mold and oxidation from damaging the grain. Grain stored in this way can remain edible for approximately five years.

Nitrogen gas (N2) at concentrations of 98% or higher is also used effectively to kill insects in the grain through hypoxia. However, carbon dioxide has an advantage in this respect, as it kills organisms through hypercarbia and hypoxia (depending on concentration), but it requires concentrations of above 35%, or so. This makes carbon dioxide preferable for fumigation in situations where a hermetic seal cannot be maintained.

Controlled Atmospheric Storage (CA): "CA storage is a

non-chemical process. Oxygen levels in the sealed rooms are reduced,

usually by the infusion of nitrogen gas, from the approximate 21 percent

in the air we breathe to 1 percent or 2 percent. Temperatures are kept

at a constant 0–2 °C (32–36 °F). Humidity is maintained at 95 percent

and carbon dioxide levels are also controlled. Exact conditions in the

rooms are set according to the apple variety. Researchers develop

specific regimens for each variety to achieve the best quality.

Computers help keep conditions constant."

"Eastern Washington, where most of Washington’s apples are grown, has

enough warehouse storage for 181 million boxes of fruit, according to a

report done in 1997 by managers for the Washington State Department of

Agriculture Plant Services Division. The storage capacity study shows

that 67 percent of that space—enough for 121,008,000 boxes of apples—is

CA storage."

Air-tight storage of grains (sometimes called hermetic storage)

relies on the respiration of grain, insects, and fungi that can modify

the enclosed atmosphere sufficiently to control insect pests. This is a

method of great antiquity,

as well as having modern equivalents. The success of the method relies

on having the correct mix of sealing, grain moisture, and temperature.

A patented process uses fuel cells to exhaust and automatically maintain the exhaustion of oxygen in a shipping container, containing, for example, fresh fish.

Nonthermal plasma

This process subjects the surface of food to a "flame" of ionized gas

molecules, such as helium or nitrogen. This causes micro-organisms to

die off on the surface.

High-pressure food preservation

High-pressure food preservation or pascalization refers to the use of a food preservation technique that makes use of high pressure.

"Pressed inside a vessel exerting 70,000 pounds per square inch

(480 MPa) or more, food can be processed so that it retains its fresh

appearance, flavor, texture and nutrients while disabling harmful

microorganisms and slowing spoilage." By 2005, the process was being

used for products ranging from orange juice to guacamole to deli meats and widely sold.

Biopreservation

3D stick model of nisin. Some lactic acid bacteria manufacture nisin. It is a particularly effective preservative.

Biopreservation is the use of natural or controlled microbiota or antimicrobials as a way of preserving food and extending its shelf life. Beneficial bacteria or the fermentation products produced by these bacteria are used in biopreservation to control spoilage and render pathogens inactive in food. It is a benign ecological approach which is gaining increasing attention.

Of special interest are lactic acid bacteria

(LAB). Lactic acid bacteria have antagonistic properties that make them

particularly useful as biopreservatives. When LABs compete for

nutrients, their metabolites often include active antimicrobials such as lactic acid, acetic acid, hydrogen peroxide, and peptide bacteriocins. Some LABs produce the antimicrobial nisin, which is a particularly effective preservative.

These days, LAB bacteriocins are used as an integral part of hurdle technology.

Using them in combination with other preservative techniques can

effectively control spoilage bacteria and other pathogens, and can

inhibit the activities of a wide spectrum of organisms, including

inherently resistant Gram-negative bacteria.

Hurdle technology

Hurdle technology is a method of ensuring that pathogens in food products

can be eliminated or controlled by combining more than one approach.

These approaches can be thought of as "hurdles" the pathogen has to

overcome if it is to remain active in the food. The right combination of

hurdles can ensure all pathogens are eliminated or rendered harmless in

the final product.

Hurdle technology has been defined by Leistner (2000) as an intelligent combination of hurdles that secures the microbial safety and stability as well as the organoleptic and nutritional quality and the economic viability of food products. The organoleptic quality of the food refers to its sensory properties, that is its look, taste, smell, and texture.

Examples of hurdles in a food system are high temperature during processing, low temperature during storage, increasing the acidity, lowering the water activity or redox potential, and the presence of preservatives or biopreservatives.

According to the type of pathogens and how risky they are, the

intensity of the hurdles can be adjusted individually to meet consumer

preferences in an economical way, without sacrificing the safety of the

product.

| Principal hurdles used for food preservation (after Leistner, 1995) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Symbol | Application |

| High temperature | F | Heating |

| Low temperature | T | Chilling, freezing |

| Reduced water activity | aw | Drying, curing, conserving |

| Increased acidity | pH | Acid addition or formation |

| Reduced redox potential | Eh | Removal of oxygen or addition of ascorbate |

| Biopreservatives |

|

Competitive flora such as microbial fermentation |

| Other preservatives |

| Sorbates, sulfites, nitrites |