The frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan

A state is a polity under a system of governance. There is no undisputed definition of a state. A widely used definition from the German sociologist Max Weber is that a "state" is a polity that maintains a monopoly on the legitimate use of violence, although other definitions are not uncommon.

Some states are sovereign (known as sovereign states), while others are subject to external sovereignty or hegemony, wherein supreme authority lies in another state. The term "state" also applies to federated states that are members of a federation, in which sovereignty is shared between member states and a federal body.

Speakers of American English often use the terms "state" and "government" as synonyms, with both words referring to an organized political group that exercises authority over a particular territory. In British and Commonwealth English, "state" is the only term that has that meaning, while "the government" instead refers to the ministers and officials who set the political policy for the territory, something that speakers of American English refer to as "the administration".

Most of the human population has existed within a state system for millennia; however, for most of prehistory people lived in stateless societies. The first states arose about 5,500 years ago in conjunction with rapid growth of cities, invention of writing and codification of new forms of religion. Over time, a variety of different forms developed, employing a variety of justifications for their existence (such as divine right, the theory of the social contract, etc.). Today, the modern nation state is the predominant form of state to which people are subject.

Etymology

The word state and its cognates in some other European languages (stato in Italian, estado in Spanish and Portuguese, état in French, Staat in German) ultimately derive from the Latin word status, meaning "condition, circumstances".

The English noun state in the generic sense "condition, circumstances" predates the political sense. It is introduced to Middle English c. 1200 both from Old French and directly from Latin.

With the revival of the Roman law in 14th-century Europe, the term came to refer to the legal standing of persons (such as the various "estates of the realm"

– noble, common, and clerical), and in particular the special status of

the king. The highest estates, generally those with the most wealth and

social rank, were those that held power. The word also had associations

with Roman ideas (dating back to Cicero) about the "status rei publicae",

the "condition of public matters". In time, the word lost its reference

to particular social groups and became associated with the legal order

of the entire society and the apparatus of its enforcement.

The early 16th-century works of Machiavelli (especially The Prince) played a central role in popularizing the use of the word "state" in something similar to its modern sense. The contrasting of church and state still dates to the 16th century. The North American colonies were called "states" as early as the 1630s. The expression L'Etat, c'est moi ("I am the State") attributed to Louis XIV of France is probably apocryphal, recorded in the late 18th century.

Definition

There is no academic consensus on the most appropriate definition of the state.

The term "state" refers to a set of different, but interrelated and

often overlapping, theories about a certain range of political phenomena.

The act of defining the term can be seen as part of an ideological

conflict, because different definitions lead to different theories of

state function, and as a result validate different political strategies. According to Jeffrey and Painter,

"if we define the 'essence' of the state in one place or era, we are

liable to find that in another time or space something which is also

understood to be a state has different 'essential' characteristics".

Different definitions of the state often place an emphasis either

on the ‘means’ or the ‘ends’ of states. Means-related definitions

include those by Max Weber and Charles Tilly, both of whom define the

state according to its violent means. For Weber, the state "is a human

community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use

of physical force within a given territory" (Politics as a Vocation),

while Tilly characterises them as "coercion-wielding organisations"

(Coercion, Capital, and European States).

Ends-related definitions emphasis instead the teleological aims

and purposes of the state. Marxist thought regards the ends of the state

as being the perpetuation of class domination in favour of the ruling

class which, under the capitalist mode of production, is the

bourgeoisie. The state exists to defend the ruling class's claims to

private property and its capturing of surplus profits at the expense of

the proletariat. Indeed, Marx claimed that "the executive of the modern

state is nothing but a committee for managing the common affairs of the

whole bourgeoisie" (Communist Manifesto).

Liberal thought provides another possible teleology of the state.

According to John Locke, the goal of the state/commonwealth was "the

preservation of property" (Second Treatise on Government), with

'property' in Locke's work referring not only to personal possessions

but also to one's life and liberty. On this account, the state provides

the basis for social cohesion and productivity, creating incentives for

wealth creation by providing guarantees of protection for one's life,

liberty and personal property.

The most commonly used definition is Max Weber's, which describes the state as a compulsory political organization with a centralized government that maintains a monopoly of the legitimate use of force within a certain territory. General categories of state institutions include administrative bureaucracies, legal systems, and military or religious organizations.

Another commonly accepted definition of the state is the one given at the Montevideo Convention

on Rights and Duties of States in 1933. It provides that "[t]he state

as a person of international law should possess the following

qualifications: (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c)

government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other

states." And that "[t]he federal state shall constitute a sole person in the eyes of international law."

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, a state is "a. an organized political community under one government; a commonwealth; a nation. b. such a community forming part of a federal republic, esp the United States of America".

Confounding the definition problem is that "state" and

"government" are often used as synonyms in common conversation and even

some academic discourse. According to this definition schema, the states

are nonphysical persons of international law, governments are organizations of people. The relationship between a government and its state is one of representation and authorized agency.

Types of states

States may be classified by political philosophers as sovereign if they are not dependent on, or subject to any other power or state. Other states are subject to external sovereignty or hegemony where ultimate sovereignty lies in another state. Many states are federated states which participate in a federal union. A federated state is a territorial and constitutional community forming part of a federation. (Compare confederacies or confederations such as Switzerland.) Such states differ from sovereign states in that they have transferred a portion of their sovereign powers to a federal government.

One can commonly and sometimes readily (but not necessarily

usefully) classify states according to their apparent make-up or focus.

The concept of the nation-state, theoretically or ideally co-terminous

with a "nation", became very popular by the 20th century in Europe, but

occurred rarely elsewhere or at other times. In contrast, some states

have sought to make a virtue of their multi-ethnic or multi-national character (Habsburg Austria-Hungary, for example, or the Soviet Union), and have emphasised unifying characteristics such as autocracy, monarchical legitimacy, or ideology. Imperial states have sometimes promoted notions of racial superiority.

Other states may bring ideas of commonality and inclusiveness to the fore: note the res publica of ancient Rome and the Rzeczpospolita of Poland-Lithuania which finds echoes in the modern-day republic. The concept of temple states centred on religious shrines occurs in some discussions of the ancient world.

Relatively small city-states, once a relatively common and often successful form of polity,

have become rarer and comparatively less prominent in modern times, although a number of them survive as federated states, like the present day German city-states, or as otherwise autonomous entities with limited sovereignty, like Hong Kong, Gibraltar and Ceuta. To some extent, urban secession,

the creation of a new city-state (sovereign or federated), continues to

be discussed in the early 21st century in cities such as London.

State and government

A state can be distinguished from a government. The state is the organization while the government is the particular group of people, the administrative bureaucracy that controls the state apparatus at a given time.

That is, governments are the means through which state power is

employed. States are served by a continuous succession of different

governments. States are immaterial and nonphysical social objects, whereas governments are groups of people with certain coercive powers.

Each successive government is composed of a specialized and

privileged body of individuals, who monopolize political

decision-making, and are separated by status and organization from the

population as a whole.

States and nation-states

States can also be distinguished from the concept of a "nation", where "nation" refers to a cultural-political community of people. A nation-state refers to a situation where a single ethnicity is associated with a specific state.

State and civil society

In the classical thought, the state was identified with both political society and civil society as a form of political community, while the modern thought distinguished the nation state as a political society from civil society as a form of economic society.

Thus in the modern thought the state is contrasted with civil society.

Antonio Gramsci

believed that civil society is the primary locus of political activity

because it is where all forms of "identity formation, ideological

struggle, the activities of intellectuals, and the construction of hegemony

take place." and that civil society was the nexus connecting the

economic and political sphere. Arising out of the collective actions of

civil society is what Gramsci calls "political society", which Gramsci

differentiates from the notion of the state as a polity. He stated that

politics was not a "one-way process of political management" but,

rather, that the activities of civil organizations conditioned the

activities of political parties and state institutions, and were

conditioned by them in turn. Louis Althusser argued that civil organizations such as church, schools, and the family

are part of an "ideological state apparatus" which complements the

"repressive state apparatus" (such as police and military) in

reproducing social relations.

Jürgen Habermas spoke of a public sphere that was distinct from both the economic and political sphere.

Given the role that many social groups have in the development of

public policy and the extensive connections between state bureaucracies

and other institutions, it has become increasingly difficult to

identify the boundaries of the state. Privatization, nationalization, and the creation of new regulatory

bodies also change the boundaries of the state in relation to society.

Often the nature of quasi-autonomous organizations is unclear,

generating debate among political scientists on whether they are part of

the state or civil society. Some political scientists thus prefer to

speak of policy networks and decentralized governance in modern

societies rather than of state bureaucracies and direct state control

over policy.

History

The earliest forms of the state emerged whenever it became possible to centralize power in a durable way. Agriculture and writing are almost everywhere associated with this process: agriculture because it allowed for the emergence of a social class

of people who did not have to spend most of their time providing for

their own subsistence, and writing (or an equivalent of writing, like Inca quipus) because it made possible the centralization of vital information.

The first known states were created in the Fertile Crescent, India, China, Mesoamerica, the Andes, and others, but it is only in relatively modern times that states have almost completely displaced alternative "stateless" forms of political organization of societies all over the planet. Roving bands of hunter-gatherers and even fairly sizable and complex tribal societies based on herding or agriculture

have existed without any full-time specialized state organization, and

these "stateless" forms of political organization have in fact prevailed

for all of the prehistory and much of the history of the human species and civilization.

Initially states emerged over territories built by conquest in which one culture, one set of ideals and one set of laws have been imposed by force or threat over diverse nations by a civilian and military bureaucracy. Currently, that is not always the case and there are multinational states, federated states and autonomous areas within states.

Since the late 19th century, virtually the entirety of the

world's inhabitable land has been parcelled up into areas with more or

less definite borders claimed by various states. Earlier, quite large

land areas had been either unclaimed or uninhabited, or inhabited by nomadic peoples who were not organised as states. However, even within present-day states there are vast areas of wilderness, like the Amazon rainforest, which are uninhabited or inhabited solely or mostly by indigenous people (and some of them remain uncontacted).

Also, there are states which do not hold de facto control over all of

their claimed territory or where this control is challenged. Currently

the international community comprises around 200 sovereign states, the vast majority of which are represented in the United Nations.

Pre-historic stateless societies

For most of human history, people have lived in stateless societies, characterized by a lack of concentrated authority, and the absence of large inequalities in economic and political power.

The anthropologist Tim Ingold writes:

It is not enough to observe, in a now rather dated anthropological idiom, that hunter gatherers live in 'stateless societies', as though their social lives were somehow lacking or unfinished, waiting to be completed by the evolutionary development of a state apparatus. Rather, the principal of their socialty, as Pierre Clastres has put it, is fundamentally against the state.

Neolithic period

During the Neolithic period, human societies underwent major cultural and economic changes, including the development of agriculture,

the formation of sedentary societies and fixed settlements, increasing

population densities, and the use of pottery and more complex tools.

Sedentary agriculture led to the development of property rights, domestication of plants and animals, and larger family sizes. It also provided the basis for the centralized state form by producing a large surplus of food, which created a more complex division of labor by enabling people to specialize in tasks other than food production. Early states were characterized by highly stratified societies, with a privileged and wealthy ruling class that was subordinate to a monarch.

The ruling classes began to differentiate themselves through forms of

architecture and other cultural practices that were different from those

of the subordinate laboring classes.

In the past, it was suggested that the centralized state was

developed to administer large public works systems (such as irrigation

systems) and to regulate complex economies. However, modern

archaeological and anthropological evidence does not support this

thesis, pointing to the existence of several non-stratified and

politically decentralized complex societies.

Ancient Eurasia

Mesopotamia is generally considered to be the location of the earliest civilization or complex society, meaning that it contained cities, full-time division of labor, social concentration of wealth into capital, unequal distribution of wealth, ruling classes, community ties based on residency rather than kinship, long distance trade, monumental architecture, standardized forms of art and culture, writing, and mathematics and science. It was the world's first literate civilization, and formed the first sets of written laws.

Classical antiquity

Painting of Roman Senators encircling Julius Caesar

Although state-forms existed before the rise of the Ancient Greek

empire, the Greeks were the first people known to have explicitly

formulated a political philosophy of the state, and to have rationally

analyzed political institutions. Prior to this, states were described

and justified in terms of religious myths.

Several important political innovations of classical antiquity came from the Greek city-states and the Roman Republic. The Greek city-states before the 4th century granted citizenship rights to their free population, and in Athens these rights were combined with a directly democratic form of government that was to have a long afterlife in political thought and history.

Feudal state

During Medieval times in Europe, the state was organized on the principle of feudalism, and the relationship between lord and vassal became central to social organization. Feudalism led to the development of greater social hierarchies.

The formalization of the struggles over taxation between the

monarch and other elements of society (especially the nobility and the

cities) gave rise to what is now called the Standestaat,

or the state of Estates, characterized by parliaments in which key

social groups negotiated with the king about legal and economic matters.

These estates of the realm

sometimes evolved in the direction of fully-fledged parliaments, but

sometimes lost out in their struggles with the monarch, leading to

greater centralization of lawmaking and military power in his hands.

Beginning in the 15th century, this centralizing process gives rise to

the absolutist state.

Modern state

Cultural and national homogenization figured prominently in the rise

of the modern state system. Since the absolutist period, states have

largely been organized on a national basis. The concept of a national state, however, is not synonymous with nation state. Even in the most ethnically homogeneous societies there is not always a complete correspondence between state and nation, hence the active role often taken by the state to promote nationalism through emphasis on shared symbols and national identity.

Theories of state function

Most political theories of the state can roughly be classified into

two categories. The first are known as "liberal" or "conservative"

theories, which treat capitalism

as a given, and then concentrate on the function of states in

capitalist society. These theories tend to see the state as a neutral

entity separated from society and the economy. Marxist and anarchist

theories on the other hand, see politics as intimately tied in with

economic relations, and emphasize the relation between economic power

and political power. They see the state as a partisan instrument that primarily serves the interests of the upper class.

Anarchist perspective

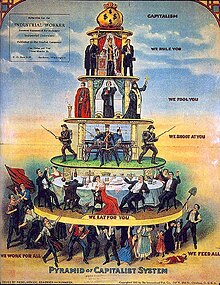

IWW poster "Pyramid of Capitalist System" (c. 1911), depicting an anti-capitalist perspective on statist/capitalist social structures

Anarchism is a political philosophy which considers the state and hierarchies to be immoral, unnecessary and harmful and instead promotes a stateless society, or anarchy, a self-managed, self-governed society based on voluntary, cooperative institutions.

Anarchists believe that the state is inherently an instrument of

domination and repression, no matter who is in control of it. Anarchists

note that the state possesses the monopoly on the legal use of violence.

Unlike Marxists, anarchists believe that revolutionary seizure of state

power should not be a political goal. They believe instead that the

state apparatus should be completely dismantled, and an alternative set

of social relations created, which are not based on state power at all.

Various Christian anarchists, such as Jacques Ellul, have identified the State and political power as the Beast in the Book of Revelation.

Marxist perspective

Marx and Engels were clear in that the communist goal was a classless society in which the state would have "withered away", replaced only by "administration of things". Their views are found throughout their Collected Works,

and address past or then extant state forms from an analytical and

tactical viewpoint, but not future social forms, speculation about which

is generally antithetical to groups considering themselves Marxist but

who – not having conquered the existing state power(s) – are not in the

situation of supplying the institutional form of an actual society. To

the extent that it makes sense,

there is no single "Marxist theory of state", but rather several

different purportedly "Marxist" theories have been developed by

adherents of Marxism.

Marx's early writings portrayed the bourgeois state as parasitic, built upon the superstructure of the economy, and working against the public interest. He also wrote that the state mirrors class

relations in society in general, acting as a regulator and repressor of

class struggle, and as a tool of political power and domination for the

ruling class. The Communist Manifesto claimed that the state to be nothing more than "a committee for managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie.

For Marxist theorists, the role of the modern bourgeois state is determined by its function in the global capitalist order. Ralph Miliband

argued that the ruling class uses the state as its instrument to

dominate society by virtue of the interpersonal ties between state

officials and economic elites. For Miliband, the state is dominated by

an elite that comes from the same background as the capitalist class.

State officials therefore share the same interests as owners of capital

and are linked to them through a wide array of social, economic, and political ties.

Gramsci's theories of state emphasized that the state is only one of the institutions in society that helps maintain the hegemony of the ruling class, and that state power is bolstered by the ideological domination of the institutions of civil society, such as churches, schools, and mass media.

Pluralism

Pluralists

view society as a collection of individuals and groups, who are

competing for political power. They then view the state as a neutral

body that simply enacts the will of whichever groups dominate the

electoral process. Within the pluralist tradition, Robert Dahl developed the theory of the state as a neutral arena for contending interests or its agencies as simply another set of interest groups.

With power competitively arranged in society, state policy is a product

of recurrent bargaining. Although pluralism recognizes the existence of

inequality, it asserts that all groups have an opportunity to pressure

the state. The pluralist approach suggests that the modern democratic

state's actions are the result of pressures applied by a variety of

organized interests. Dahl called this kind of state a polyarchy.

Pluralism has been challenged on the ground that it is not

supported by empirical evidence. Citing surveys showing that the large

majority of people in high leadership positions are members of the

wealthy upper class, critics of pluralism claim that the state serves

the interests of the upper class rather than equitably serving the

interests of all social groups.

Contemporary critical perspectives

Jürgen Habermas

believed that the base-superstructure framework, used by many Marxist

theorists to describe the relation between the state and the economy,

was overly simplistic. He felt that the modern state plays a large role

in structuring the economy, by regulating economic activity and being a

large-scale economic consumer/producer, and through its redistributive welfare state

activities. Because of the way these activities structure the economic

framework, Habermas felt that the state cannot be looked at as passively

responding to economic class interests.

Michel Foucault

believed that modern political theory was too state-centric, saying

"Maybe, after all, the state is no more than a composite reality and a

mythologized abstraction, whose importance is a lot more limited than

many of us think." He thought that political theory was focusing too

much on abstract institutions, and not enough on the actual practices of

government. In Foucault's opinion, the state had no essence. He

believed that instead of trying to understand the activities of

governments by analyzing the properties of the state (a reified

abstraction), political theorists should be examining changes in the

practice of government to understand changes in the nature of the state.

Foucault argues that it is technology that has created and made the

state so elusive and successful, and that instead of looking at the

state as something to be toppled we should look at the state as

technological manifestation or system with many heads; Foucault argues

instead of something to be overthrown as in the sense of the Marxist and Anarchist

understanding of the state. Every single scientific technological

advance has come to the service of the state Foucault argues and it is

with the emergence of the Mathematical sciences and essentially the

formation of Mathematical statistics

that one gets an understanding of the complex technology of producing

how the modern state was so successfully created. Foucault insists that

the Nation state

was not a historical accident but a deliberate production in which the

modern state had to now manage coincidentally with the emerging practice

of the Police (Cameral science) 'allowing' the population to now 'come in' into jus gentium and civitas (Civil society) after deliberately being excluded for several millennia. Democracy

wasn't (the newly formed voting franchise) as is always painted by both

political revolutionaries and political philosophers as a cry for

political freedom or wanting to be accepted by the 'ruling elite',

Foucault insists, but was a part of a skilled endeavour of switching

over new technology such as; Translatio imperii, Plenitudo potestatis and extra Ecclesiam nulla salus

readily available from the past Medieval period, into mass persuasion

for the future industrial 'political' population(deception over the

population) in which the political population was now asked to insist

upon itself "the president must be elected". Where these political

symbol agents, represented by the pope and the president are now

democratised. Foucault calls these new forms of technology Biopower and form part of our political inheritance which he calls Biopolitics.

Heavily influenced by Gramsci, Nicos Poulantzas, a Greek neo-Marxist

theorist argued that capitalist states do not always act on behalf of

the ruling class, and when they do, it is not necessarily the case

because state officials consciously strive to do so, but because the 'structural'

position of the state is configured in such a way to ensure that the

long-term interests of capital are always dominant. Poulantzas' main

contribution to the Marxist literature on the state was the concept of

'relative autonomy' of the state. While Poulantzas' work on 'state

autonomy' has served to sharpen and specify a great deal of Marxist

literature on the state, his own framework came under criticism for its 'structural functionalism'.

State autonomy within institutionalism

State autonomy theorists believe that the state is an entity that is

impervious to external social and economic influence, and has interests

of its own.

"New institutionalist" writings on the state, such as the works of Theda Skocpol,

suggest that state actors are to an important degree autonomous. In

other words, state personnel have interests of their own, which they can

and do pursue independently of (at times in conflict with) actors in

society. Since the state controls the means of coercion, and given the

dependence of many groups in civil society on the state for achieving

any goals they may espouse, state personnel can to some extent impose

their own preferences on civil society.

Theories of state legitimacy

States generally rely on a claim to some form of political legitimacy in order to maintain domination over their subjects.

Divine right of kings

The rise of the modern day state system was closely related to

changes in political thought, especially concerning the changing

understanding of legitimate state power and control. Early modern

defenders of absolutism (Absolute monarchy), such as Thomas Hobbes and Jean Bodin undermined the doctrine of the divine right of kings

by arguing that the power of kings should be justified by reference to

the people. Hobbes in particular went further to argue that political

power should be justified with reference to the individual(Hobbes wrote

in the time of the English Civil War),

not just to the people understood collectively. Both Hobbes and Bodin

thought they were defending the power of kings, not advocating for

democracy, but their arguments about the nature of sovereignty were

fiercely resisted by more traditional defenders of the power of kings,

such as Sir Robert Filmer in England, who thought that such defenses ultimately opened the way to more democratic claims.

Rational-legal authority

Max Weber identified three main sources of political legitimacy in

his works. The first, legitimacy based on traditional grounds is derived

from a belief that things should be as they have been in the past, and

that those who defend these traditions have a legitimate claim to power.

The second, legitimacy based on charismatic leadership, is devotion to a

leader or group that is viewed as exceptionally heroic or virtuous. The

third is rational-legal authority,

whereby legitimacy is derived from the belief that a certain group has

been placed in power in a legal manner, and that their actions are

justifiable according to a specific code of written laws. Weber believed

that the modern state is characterized primarily by appeals to

rational-legal authority.

State failure

Some states are often labeled as "weak" or "failed". In David Samuels's words "...a failed state occurs when sovereignty over claimed territory has collapsed or was never effectively at all". Authors like Samuels and Joel S. Migdal

have explored the emergence of weak states, how they are different from

Western "strong" states and its consequences to the economic

development of developing countries.

Early state formation

To understand the formation of weak states, Samuels

compares the formation of European states in the 1600s with the

conditions under which more recent states were formed in the twentieth

century. In this line of argument, the state allows a population to

resolve a collective action problem, in which citizens recognize the

authority of the state and this exercise the power of coercion over

them. This kind of social organization required a decline in legitimacy

of traditional forms of ruling (like religious authorities) and replaced

them with an increase in the legitimacy of depersonalized rule; an

increase in the central government's sovereignty; and an increase in the

organizational complexity of the central government (bureaucracy).

The transition to this modern state was possible in Europe around

1600 thanks to the confluence of factors like the technological

developments in warfare, which generated strong incentives to tax and

consolidate central structures of governance to respond to external

threats. This was complemented by the increasing on the production of

food (as a result of productivity improvements), which allowed to

sustain a larger population and so increased the complexity and

centralization of states. Finally, cultural changes challenged the

authority of monarchies and paved the way to the emergence of modern

states.

Late state formation

The conditions that enabled the emergence of modern states in

Europe were different for other countries that started this process

later. As a result, many of these states lack effective capabilities to

tax and extract revenue from their citizens, which derives in problems

like corruption, tax evasion and low economic growth. Unlike the

European case, late state formation occurred in a context of limited

international conflict that diminished the incentives to tax and

increase military spending. Also, many of these states emerged from

colonization in a state of poverty and with institutions designed to

extract natural resources, which have made more difficult to form

states. European colonization also defined many arbitrary borders that

mixed different cultural groups under the same national identities,

which has made difficult to build states with legitimacy among all the

population, since some states have to compete for it with other forms of

political identity.

As a complement of this argument, Migdal gives a historical account on how sudden social changes in the Third World during the Industrial Revolution

contributed to the formation of weak states. The expansion of

international trade that started around 1850, brought profound changes

in Africa, Asia and Latin America that were introduced with the

objective of assure the availability of raw materials for the European

market. These changes consisted in: i) reforms to landownership laws

with the objective of integrate more lands to the international economy,

ii) increase in the taxation of peasants and little landowners, as well

as collecting of these taxes in cash instead of in kind as was usual up

to that moment and iii) the introduction of new and less costly modes

of transportation, mainly railroads. As a result, the traditional forms

of social control became obsolete, deteriorating the existing

institutions and opening the way to the creation of new ones, that not

necessarily lead these countries to build strong states.

This fragmentation of the social order induced a political logic in

which these states were captured to some extent by "strongmen", who were

capable to take advantage of the above-mentioned changes and that

challenge the sovereignty of the state. As a result, these

decentralization of social control impedes to consolidate strong states.