Climate change adaptation is the process of adjusting to current or expected climate change and its effects. It is one of the ways to respond to climate change, along with climate change mitigation. For humans, adaptation aims to moderate or avoid harm, and exploit opportunities; for natural systems, humans may intervene to help adjustment. Without mitigation, adaptation alone cannot avert the risk of "severe, widespread and irreversible" impacts.

Adaptation actions can be either incremental (actions where the central aim is to maintain the essence and integrity of a system) or transformational (actions that change the fundamental attributes of a system in response to climate change and its impacts).

The need for adaptation varies from place to place, depending on the sensitivity and vulnerability to environmental impacts. Adaptation is especially important in developing countries since those countries are most vulnerable to climate change and are bearing the brunt of the effects of global warming. Human adaptive capacity is unevenly distributed across different regions and populations, and developing countries generally have less capacity to adapt. Adaptive capacity is closely linked to social and economic development. The economic costs of adaptation to climate change are likely to cost billions of dollars annually for the next several decades, though the exact amount of money needed is unknown.

The adaptation challenge grows with the magnitude and the rate of climate change. Even the most effective climate change mitigation through reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or enhanced removal of these gases from the atmosphere (through carbon sinks) would not prevent further climate change impacts, making the need for adaptation unavoidable. The Paris Agreement requires countries to keep global temperature rise this century to less than 2 °C above pre-industrial levels, and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C. Even if emissions are stopped relatively soon, global warming and its effects will last many years due to the inertia of the climate system, so both net zero and adaptation are necessary.

Sustainable Development Goal 13, set in 2015, targets to strengthen countries' resilience and adaptive capacities to climate-related issues. This adjustment includes many areas such as infrastructure, agriculture and education. The Paris Agreement, adopted in the same year, included several provisions for adaptation. It seeks to promote the idea of global responsibility, improve communication via the adaption component of the Nationally Determined Contributions, and includes an agreement that developed countries should provide some financial support and technology transfer to promote adaptation in more vulnerable countries. Some scientists are concerned that climate adaptation programs might interfere with the existing development programs and thus lead to unintended consequences for vulnerable groups. The economic and social costs of unmitigated climate change would be very high.

Effects of global warming

The projected effects for the environment and for civilization are numerous and varied. The main effect is an increasing global average temperature. As of 2013 the average surface temperature could increase by a further 0.3 to 4.8 °C (0.5 to 8.6 °F) by the end of the century. This causes a variety of secondary effects, namely, changes in patterns of precipitation, rising sea levels, altered patterns of agriculture, increased extreme weather events, the expansion of the range of tropical diseases, and the opening of new marine trade routes; that without taking into account the social effects of climate change as inequity, pollution and diseases, environmental injustice and poverty.

Potential effects include sea level rise of 110 to 770 mm (0.36 to 2.5 feet) between 1990 and 2100, repercussions to agriculture, possible slowing of the thermohaline circulation, reductions in the ozone layer, increased intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, lowering of ocean pH, and the spread of tropical diseases such as malaria and dengue fever.

Adaptation is handicapped by uncertainty over the effects of global warming on specific locations such as the Southwestern United States or phenomena such as the Indian monsoon predicted to increase in frequency and intensity.

Risk factors

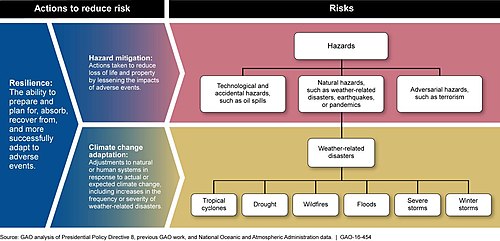

Adaptation can help decrease climate risk via the three risk factors: hazards, vulnerability and exposure. Climate hazards may be reduced with the help of ecosystem-based adaptation. For instance, flooding may be prevented if mangroves have the ability to dampen storm energy. As such, protection of the mangrove ecosystem can be a form of adaptation. Insurance and livelihood diversification increase resilience and decrease vulnerability. Further actions to decrease vulnerability include strengthening social protection and building infrastructure more resistant to hazards. Exposure can be decreased by retreating from areas with high climate risks, and by improving systems for early warnings and evacuations.

Adaptation options

Local adaptation efforts

Cities, states, and provinces often have considerable responsibility in land use planning, public health, and disaster management. Some have begun to take steps to adapt to threats intensified by climate change, such as flooding, bushfires, heatwaves, and rising sea levels.

Projects to deal with heat include:

- Incentivizing lighter-colored roofs to reduce the heat island effect

- Adding air conditioning in public schools

- Changing to heat tolerant tree varieties

- Adding green roofs to deal with rainwater and heat

There is also a wide variety of adaptation options for flooding:

- Installing protective and/ or resilient technologies and materials in properties that are prone to flooding

- Rainwater storage to deal with more frequent flooding rainfall – Changing to water-permeable pavements, adding water-buffering vegetation, adding underground storage tanks, subsidizing household rain barrels

- Reducing paved areas to deal with rainwater and heat

- Requiring waterfront properties to have higher foundations

- Raising pumps at wastewater treatment plants

- Surveying local vulnerabilities, raising public awareness, and making climate change-specific planning tools like future flood maps

- Installing devices to prevent seawater from backflowing into storm drains

- Installing better flood defenses, such as sea walls and increased pumping capacity

- Buying out homeowners in flood-prone areas

- Raising street level to prevent flooding

Dealing with more frequent drenching rains may required increasing the capacity of stormwater systems, and separating stormwater from blackwater, so that overflows in peak periods do not contaminate rivers. One example is the SMART Tunnel in Kuala Lumpur.

New York City produced a comprehensive report for its Rebuilding and Resiliency initiative after Hurricane Sandy. Its efforts include not only making buildings less prone to flooding, but taking steps to reduce the future recurrence of specific problems encountered during and after the storm: weeks-long fuel shortages even in unaffected areas due to legal and transportation problems, flooded health care facilities, insurance premium increases, damage to electricity and steam generation in addition to distribution networks, and flooding of subway and roadway tunnels.

Enhancing adaptive capacity

Adaptive capacity is the ability of a system (human, natural or managed) to adjust to climate change (including climate variability and extremes) to moderate potential damages, to take advantage of opportunities, or to cope with consequences. As a property, adaptive capacity is distinct from adaptation itself. Those societies that can respond to change quickly and successfully have a high adaptive capacity. High adaptive capacity does not necessarily translate into successful adaptation. For example, adaptive capacity in Western Europe is generally considered to be high, and the risks of warmer winters increasing the range of livestock diseases is well documented, but many parts of Europe were still badly affected by outbreaks of the Bluetongue virus in livestock in 2007.

Unmitigated climate change (i.e., future climate change without efforts to limit greenhouse gas emissions) would, in the long term, be likely to exceed the capacity of natural, managed and human systems to adapt.

It has been found that efforts to enhance adaptive capacity can help to reduce vulnerability to climate change. In many instances, activities to promote sustainable development can also act to enhance people's adaptive capacity to climate change. These activities can include:

- Improving access to resources

- Reducing poverty

- Lowering inequities of resources and wealth among groups

- Improving education and information

- Improving infrastructure

- Improving institutional capacity and efficiency

- Promoting local indigenous practices, knowledge, and experiences

Others have suggested that certain forms of gender inequity should be addressed at the same time; for example women may have participation in decision-making, or be constrained by lower levels of education.

Researchers at the Overseas Development Institute found that development interventions to increase adaptive capacity have tended not to result in increased agency for local people. They argue that this should play a more prominent part in future intervention planning because agency is a central factor in all other aspects of adaptive capacity. Asset holdings and the ability to convert these resources through institutional and market processes are central to agency.

Agricultural production

A significant effect of global climate change is the altering of global rainfall patterns, with certain effects on agriculture. Rainfed agriculture constitutes 80% of global agriculture. Many of the 852 million poor people in the world live in parts of Asia and Africa that depend on rainfall to cultivate food crops. Climate change will modify rainfall, evaporation, runoff, and soil moisture storage. Extended drought can cause the failure of small and marginal farms with resultant economic, political and social disruption, more so than this currently occurs.

Agriculture of any kind is strongly influenced by the availability of water. Changes in total seasonal precipitation or in its pattern of variability are both important. The occurrence of moisture stress during flowering, pollination, and grain-filling is harmful to most crops and particularly so to corn, soybeans, and wheat. Increased evaporation from the soil and accelerated transpiration in the plants themselves will cause moisture stress.

Adaptive ideas include:

- Taking advantage of global transportation systems to delivering surplus food to where it is needed (though this does not help subsistence farmers unless aid is given).

- Developing crop varieties with greater drought tolerance.

- Rainwater storage. For example, according to the International Water Management Institute, using small planting basins to 'harvest' water in Zimbabwe has been shown to boost maize yields, whether rainfall is abundant or scarce. And in Niger, they have led to three or fourfold increases in millet yields.

- Falling back from crops to wild edible fruits, roots and leaves. Promoting the growth of forests can provide these backup food supplies, and also provide watershed conservation, carbon sequestration, and aesthetic value.

Reforestation

Reforestation is one of the ways to stop desertification fueled by anthropogenic climate change and non sustainable land use. One of the most important projects is the Great Green Wall that should stop the expansion of Sahara desert to the south. By 2018 only 15% of it is accomplished, but there are already many positive effects, which include: "Over 12 million acres (5 million hectares) of degraded land has been restored in Nigeria; roughly 30 million acres of drought-resistant trees have been planted across Senegal; and a whopping 37 million acres of land has been restored in Ethiopia – just to name a few of the states involved." "Many groundwater wells [were] refilled with drinking water, rural towns with additional food supplies, and new sources of work and income for villagers, thanks to the need for tree maintenance."

More spending on irrigation

The demand for water for irrigation is projected to rise in a warmer climate, bringing increased competition between agriculture—already the largest consumer of water resources in semi-arid regions—and urban as well as industrial users. Falling water tables and the resulting increase in the energy needed to pump water will make the practice of irrigation more expensive, particularly when with drier conditions more water will be required per acre. Other strategies will be needed to make the most efficient use of water resources. For example, the International Water Management Institute has suggested five strategies that could help Asia feed its growing population in light of climate change. These are:

- Modernising existing irrigation schemes to suit modern methods of farming

- Supporting farmers' efforts to find their own water supplies, by tapping into groundwater in a sustainable way

- Looking beyond conventional "Participatory Irrigation Management" schemes, by engaging the private sector

- Expanding capacity and knowledge

- Investing outside the irrigation sector

Weather control

Russian and American scientists have in the past tried to control the weather, for example by seeding clouds with chemicals to try to produce rain when and where it is needed. China has implemented a cloud seeding machine that is controlled through remote sensing technologies. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) through its Commission for Atmospheric Sciences (CAS) opined in 2007: "Purposeful augmentation of precipitation, reduction of hail damage, dispersion of fog and other types of cloud and storm modifications by cloud seeding are developing technologies which are still striving to achieve a sound scientific foundation and which have to be adapted to enormously varied natural conditions."

Against flooding

Retreat, accommodate and protect

Adaptation options to sea level rise can be broadly classified into retreat, accommodate and protect. Retreating involves moving people and infrastructure to less exposed areas and preventing further development in areas at risk. This type of adaptation is potentially disruptive, as displacement of people may lead to tensions. Accommodation options make societies more flexible to sea level rise. Examples are the cultivation of food crops that tolerate a high salt content in the soil and making new building standards which require building to be built higher and incur less damage in the case a flood does occur. Finally, areas can be protected by the construction of dams, dikes and by improving natural defenses. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency supports the development and maintenance of water supply infrastructure nationwide, especially in coastal cities, and more coastal cities and countries are actively implementing this approach. Besides, storm surges and flooding can be instantaneous and devastating to cities, and some coastal areas have begun investing in storm water valves to cope with more frequent and severe flooding during high tides.

Damming glacial lakes

Glacial lake outburst floods may become a bigger concern due to the retreat of glaciers, leaving behind numerous lakes that are impounded by often weak terminal moraine dams. In the past, the sudden failure of these dams has resulted in localized property damage, injury and deaths. Glacial lakes in danger of bursting can have their moraines replaced with concrete dams (which may also provide hydroelectric power).

Migration

Migration can be seen as adaptation: people may be able to generate more income, diversify livelihoods, and spread climate risk. This contrasts with two other frames around migration and environmental change: migration as a human's right issue and migration as a security issue. In the human right's frame, normative implications include setting up protection frameworks for migrants, whereas increased border security may be an implication of framing migration as a national security issue.

Would-be migrants often need access to social and financial capital, such as support networks in the chosen destination and the funds or physical resources to be able to move. Migration is frequently the last adaptive response households will take when confronted with environmental factors that threaten their livelihoods, and mostly resorted to when other mechanisms to cope have proven unsuccessful.

Migration events are multi-causal, with the environment being just a factor amongst many. Many discussions around migration are based on projections, while relatively few use current migration data. Migration related to sudden events like hurricanes, heavy rains, floods, and landslides is often short-distance, involuntary, and temporary. Slow-impact events, such as droughts and slowly rising temperatures, have more mixed effects. People may lose the means to migrate, leading to a net decrease in migration. The migration that does take place is seen as voluntary and economically motivated.

Focusing on climate change as the issue may frame the debate around migration in terms of projections, causing the research to be speculative. Migration as tool for climate change adaptation is projected to be a more pressing issue in the decade to come. In Africa, specifically, migrant social networks can help to build social capital to increase the social resilience in the communities of origin and trigger innovations across regions by the transfer of knowledge, technology, remittances and other resources.

In Africa, Mozambique and Zimbabwe are clear examples of adaptation strategies because they have implemented relocation policies that have reduced the exposure of populations and migrants to disaster. Tools can be put in place that limit forced displacement after a disaster; promote employment programs, even if only temporary, for internally displaced people or establish funding plans to ensure their security; to minimize the vulnerability of populations from risk areas. This can limit the displacement caused by environmental shocks and better channel the positive spillovers (money transfers, experiences, etc.) from the migration to the origin countries/communities.

Relocation from the effects of climate change has been brought to light more and more over the years from the constant increasing effects of climate change in the world. Coastal homes in the U.S. are in danger from climate change, this is leading residents to relocate to areas that are less affected. Flooding in coastal areas and drought have been the main reasons for relocation.

Insurance

Insurance spreads the financial impact of flooding and other extreme weather events. Although it can be preferable to take a proactive approach to eliminate the cause of the risk, reactive post-harm compensation can be used as a last resort. Access to reinsurance may be a form of increasing the resiliency of cities. Where there are failures in the private insurance market, the public sector can subsidize premiums. A study identified key equity issues for policy considerations:

- Transferring risk to the public purse does not reduce overall risk

- Governments can spread the cost of losses across time rather than space

- Governments can force home-owners in low risk areas to cross-subsidize the insurance premiums of those in high risk areas

- Cross-subsidization is increasingly difficult for private sector insurers operating in a competitive market

- Governments can tax people to pay for tomorrow's disaster.

Government-subsidized insurance, such as the U.S. National Flood Insurance Program, is criticized for providing a perverse incentive to develop properties in hazardous areas, thereby increasing overall risk. It is also suggested that insurance can undermine other efforts to increase adaptation, for instance through property level protection and resilience. This behavioral effect may be countered with appropriate land-use policies that limit new construction where current or future climate risks are perceived and/or encourage the adoption of resilient building codes to mitigate potential damages.

Climate services

A rather new activity in the domain of climatology applied to adaptation is the development and implementation of climate services that "provide climate information to help individuals and organizations to make climate smart decisions". Most recognized applications of climate services are in domains like agriculture, energy, disaster risk reduction, health and water. In Europe a large framework called C3S for supplying climate services has been implemented by the European Union Copernicus programme.

Adaptation in ecosystems

Ecosystems adapt to global warming depending on their resilience to climatic changes. Humans can help adaptation in ecosystems for biodiversity. Possible responses include increasing connectivity between ecosystems, allowing species to migrate to more favourable climate conditions and species relocation. Protection and restoration of natural and semi-natural areas also helps build resilience, making it easier for ecosystems to adapt.

Many of the action that promote adaptation in ecosystems, also help humans adapt via ecosystem-based adaptation. For instance, restoration of natural fire regimes makes catastophic fires less likely, and reduces the human exposure to this hazard. Giving rivers more space allows for storage of more water in the natural system, making floods in inhabited areas less likely. The provision of green spaces and tree planting creates shade for livestock. There is a trade-off between agricultural production and the restoration of ecosystems in some areas.

Measures by region

Numerous countries have planned or started adaptation measures. The Netherlands, along with the Philippines and Japan and United Nations Environment, launched the Global Centre of Excellence on Climate Adaptation in 2017.

Policies have been identified as important tools for integrating issues of climate change adaptation. At national levels, adaptation strategies may be found in National Action Plans (NAPS ) and National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA, in developing countries), and/or in national policies and strategies on climate change. These are at different levels of development in different countries.

The Americas

United States

The state of California enacted the first comprehensive state-level climate action plan with its 2009 "California Climate Adaptation Strategy." California's electrical grid has been impacted by the increased fire risks associated with climate change. In the 2019 "red flag" warning about the possibility of wildfires declared in some areas of California, the electricity company Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) was required to shut down power to prevent inflammation of trees that touch the electricity lines. Millions were impacted.

Within the state of Florida four counties (Broward, Miami-Dade, Monroe, Palm Beach) have created the Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact in order to coordinate adaptation and mitigation strategies to cope with the impact of climate change on the region. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts has issued grants to coastal cities and towns for adaptation activities such as fortification against flooding and preventing coastal erosion.

New York State is requiring climate change be taken into account in certain infrastructure permitting, zoning, and open space programs; and is mapping sea level rise along its coast. After Hurricane Sandy, New York and New Jersey accelerated voluntary government buy-back of homes in flood-prone areas. New York City announced in 2013 it planned to spend between $10 and $20 billion on local flood protection, reduction of the heat island effect with reflective and green roofs, flood-hardening of hospitals and public housing, resiliency in food supply, and beach enhancement; rezoned to allow private property owners to move critical features to upper stories; and required electrical utilities to harden infrastructure against flooding.

In 2019, a $19.1 billion "disaster relief bill" was approved by the Senate. The bill should help the victims of extreme weather that was partly fueled by climate change.

Mesoamerica

In Mesoamerica, climate change is one of the main threats to rural Central American farmers, as the region is plagued with frequent droughts, cyclones and the El Niño- Southern-Oscillation. Although there is a wide variety of adaption strategies, these can vary dramatically from country to country. Many of the adjustments that have been made are primarily agricultural or related to water supply. Some of these adaptive strategies include restoration of degraded lands, rearrangement of land uses across territories, livelihood diversification, changes to sowing dates or water harvest, and even migration. The lack of available resources in Mesoamerica continues to pose as a barrier to more substantial adaptations, so the changes made are incremental.

Europe

Climate change threatens to undermine decades of development gains in Europe and put at risk efforts to eradicate poverty. In 2013, the European Union adopted the 'EU Adaptation Strategy', which had three key objectives: (1) promoting action by member states, which includes providing funding, (2) promoting adaptation in climate-sensitive sectors and (3) research.

Germany

In 2008, the German Federal Cabinet adopted the 'German Strategy for Adaptation to Climate Change' that sets out a framework for adaptation in Germany. Priorities are to collaborate with the Federal States of Germany in assessing the risks of climate change, identifying action areas and defining appropriate goals and measures. In 2011, the Federal Cabinet adopted the 'Adaptation Action Plan' that is accompanied by other items such as research programs, adaptation assessments and systematic observations.

Greenland

In 2009 the Greenland Climate Research Centre was set up in the capital of Greenland, Nuuk. Traditional knowledge is important for weather and animal migration, as well as for adaptive capacity building in areas such as the recognition of approaching hazards and survival skills.

Asia

The Asia-Pacific climate change adaptation information platform (AP-PLAT) was launched in 2019. It aims to provide Asia and Pacific countries with data on climate change and convert it to adaptation and resilience measures.

Bangladesh

In 2018, the New York WILD film festival gave the "Best Short Film" award to a 12-minute documentary, titled Adaptation Bangladesh: Sea Level Rise. The film explores the way in which Bangladeshi farmers are preventing their farms from flooding by building floating gardens made of water hyacinth and bamboo.

India

An Ice Stupa designed by Sonam Wangchuk brings glacial water to farmers in the Himalayan Desert of Ladakh, India.

A research project conducted between 2014 and 2018 in the five districts (Puri, Khordha, Jagatsinghpur, Kendrapara and Bhadrak) of Mahanadi Delta, Odisha and two districts (North and South 24 Parganas) of Indian Bengal Delta (includes the Indian Sundarbans), West Bengal provides evidence on the kinds of adaptations practiced by the delta dwellers. In the Mahanadi delta, the top three practiced adaptations were changing the amount of fertiliser used in the farm, the use of loans, and planting of trees around the homes. In the Indian Bengal Delta, the top three adaptations were changing the amount of fertiliser used in the farm, making changes to irrigation practices, and use of loans. Migration as an adaptation option is practiced in both these deltas but is not considered as a successful adaptation.

In the Indian Sundarbans of West Bengal, farmers are cultivating salt-tolerant rice varieties which have been revived to combat the increasing issue of soil salinity. Other agricultural adaptations include mixed farming, diversifying crops, rain water harvesting, drip irrigation, use of neem-based pesticide, and ridge and farrow land shaping techniques where “the furrows help with drainage and the less-saline ridges can be used to grow vegetables.” These have helped farmers to grow a second crop of vegetables besides the monsoon paddy crop.

In Puri district of Odisha, water logging is a hazard that affects people yearly. In the Totashi village, many women are turning the "water logging in their fields to their advantage" by cultivating vegetables in the waterlogged fields and boosting their family income and nutrition.

Nepal

Africa

Africa will be one of the regions most impacted by the adverse effects of climate change. Reasons for Africa's vulnerability are diverse and include low levels of adaptive capacity, poor diffusion of technologies and information relevant to supporting adaptation, and high dependence on agro-ecosystems for livelihoods. Many countries across Africa are classified as Least-Developed Countries (LDCs) with poor socio-economic conditions, and by implication are faced with particular challenges in responding to the impacts of climate change.

Pronounced risks identified for Africa in the IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report relate to ecosystems, water availability and agricultural systems, with implications for food security. In relation to agricultural systems, heavy reliance on rain-fed subsistence farming and low adoption of climate smart agricultural practices contribute to the sector's high levels of vulnerability. The situation is compounded by poor reliability of, and access to, climate data and information to support adaptation actions. Climate change is likely to further exacerbate water-stressed catchments across Africa - for example the Rufiji basin in Tanzania - owing to diversity of land uses, and complex sociopolitical challenges.

To reduce the impacts of climate change on African countries, adaption measures are required at multiple scales - ranging from local to national and regional levels. The first generation of adaptation projects in Africa can be largely characterised as small-scale in nature, focused on targeted investments in agriculture and diffusion of technologies to support adaptive decision-making. More recently, programming efforts have re-oriented towards larger and more coordinated efforts, tackling issues that spanning multiple sectors.

At the regional level, regional policies and actions in support of adaptation across Africa are still in their infancy. The IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report (AR5) highlights examples of various regional climate change action plans, including those developed by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) and Lake Victoria Basin Committee. At the national level, many early adaptation initiatives were coordinated through National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs) or National Climate Change Response Strategies (NCCRS). Implementation has been slow however, with mixed success in delivery. Integration of climate change with wider economic and development planning remains limited but growing.

At the subnational level, many provincial and municipal authorities are also developing their own strategies, for example the Western Cape Climate Change Response Strategy. Yet, levels of technical capacity and resources available to implement plans are generally low. There has been considerable attention across Africa given to implementing community-based adaptation projects. There is broad agreement that support to local-level adaptation is best achieved by starting with existing local adaptive capacity, and engaging with indigenous knowledge and practices.

The IPCC highlights a number of successful approaches to promote effective adaptation in Africa, outlining five common principles. These include:

- Enhancing support for autonomous forms of adaptation;

- Increasing attention to the cultural, ethical, and rights considerations of adaptation (especially through active participation of women, youth, and poor and vulnerable people in adaptation activities);

- Combining “soft path” options and flexible and iterative learning approaches with technological and infrastructural approaches (including integration of scientific, local, and indigenous knowledge in developing adaptation strategies)

- Focusing on enhancing resilience and implementing low-regrets adaptation options; and

- Building adaptive management and encouraging process of social and institutional learning into adaptation activities.

Northern Africa

Key adaptations in northern Africa relate to increased risk of water scarcity (resulting from a combination of climate change affecting water availability and increasing demand). Reduced water availability, in turn, interacts with increasing temperatures to create need for adaptation among rainfed wheat production and changing disease risk (for example from leishmaniasis. Most government actions for adaptation centre on water supply side, for example through desalination, inter-basin transfers and dam construction. Migration has also been observed to act as an adaptation for individuals and households in northern Africa. Like many regions, however, examples of adaptation action (as opposed to intentions to act, or vulnerability assessments) from north Africa are limited - a systematic review published in 2011 showed that only 1 out of 87 examples of reported adaptations came from North Africa.

Western Africa

Water availability is a particular risk in Western Africa, with extreme events such as drought leading to humanitarian crises associated with periodic famines, food insecurity, population displacement, migration and conflict and insecurity. Adaptation strategies can be environmental, cultural/agronomic and economic.

Adaptation strategies are evident in the agriculture sector, some of which are developed or promoted by formal research or experimental stations. Indigenous agricultural adaptations observed in northern Ghana are crop-related, soil-related or involve cultural practices. Livestock-based agricultural adaptations include indigenous strategies such as adjusting quantities of feed to feed livestock, storing enough feed during the abundant period to be fed to livestock during the lean season, treating wounds with solution of certain barks of trees, and keeping local breeds which are already adapted to the climate of northern Ghana; and livestock production technologies to include breeding, health, feed/nutrition and housing.

The choice and adoption of adaptation strategies is variously contingent on demographic factors such as the household size, age, gender and education of the household head; economic factors such as income source; farm size; knowledge of adaptation options; and expectation of future prospects.

Eastern Africa

In Eastern Africa adaptation options are varied, including improving use of climate information, actions in the agriculture and livestock sector, and in the water sector.

Making better use of climate and weather data, weather forecasts, and other management tools enables timely information and preparedness of people in the sectors such as agriculture that depend on weather outcomes. This means mastering hydro-meteorological information and early warning systems. It has been argued that the indigenous communities possess knowledge on historical climate changes through environmental signs (e.g. appearance and migration of certain birds, butterflies etc.), and thus promoting of indigenous knowledge has been considered an important adaptation strategy.

Adaptation in the agricultural sector includes increased use of manure and crop-specific fertilizer, use of resistant varieties of crops and early maturing crops. Manure, and especially animal manure is thought to retain water and have essential microbes that breakdown nutrients making them available to plants, as compared to synthetic fertilizers that have compounds which when released to the environment due to over-use release greenhouse gases. One major vulnerability of the agriculture sector in Eastern Africa is the dependence on rain-fed agriculture. An adaptation solution is efficient irrigation mechanisms and efficient water storage and use. Drip irrigation has especially been identified as a water-efficient option as it directs the water to the root of the plant with minimal wastage. Countries like Rwanda and Kenya have prioritized developing irrigated areas by gravity water systems from perennial streams and rivers in zones vulnerable to prolonged droughts. During heavy rains, many areas experience flooding resulting from bare grounds due to deforestation and little land cover. Adaptation strategies proposed for this is promoting conservation efforts on land protection, by planting indigenous trees, protecting water catchment areas and managing grazing lands through zoning.

For the livestock sector, adaptation options include managing production through sustainable land and pasture management in the ecosystems. This includes promoting hay and fodder production methods e.g. through irrigation and use of waste treated water, and focusing on investing in hay storage for use during dry seasons. Keeping livestock is considered a livelihood rather than an economic activity. Throughout Eastern Africa Countries especially in the ASALs regions, it is argued that promoting commercialization of livestock is an adaptation option. This involves adopting economic models in livestock feed production, animal traceability, promoting demand for livestock products such as meat, milk and leather and linking to niche markets to enhance businesses and provide disposable income.

In the water sector, options include efficient use of water for households, animals and industrial consumption and protection of water sources. Campaigns such as planting indigenous trees in water catchment areas, controlling human activities near catchment areas especially farming and settlement have been carried out to help protect water resources and avail access to water for communities especially during climatic shocks.

Southern Africa

There have been several initiatives at local (site-specific), local, national and regional scales aimed at strengthening to climate change. Some of these are: The Regional Climate Change Programme (RCCP), SASSCAL, ASSAR, UNDP Climate Change Adaptation, RESILIM, FRACTAL. South Africa implemented the Long-Term Adaptation Scenarios Flagship Research Programme (LTAS) from April 2012 to June 2014. This research also produced factsheets and a technical report covering the SADC region entitled "Climate Change Adaptation: Perspectives for the Southern African Development Community (SADC)".

Effective policy

Principles for effective policy

Adaptive policy can occur at the global, national, or local scale, with outcomes dependent on the political will in that area. Scheraga and Grambsch identify nine principles to be considered when designing adaptation policy, including the effects of climate change varying by region, demographics, and effectiveness. Scheraga and Grambsch make it clear that climate change policy is impeded by the high level of variance surrounding climate change impacts as well as the diverse nature of the problems they face. James Titus, project manager for sea level rise at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, identifies the following criteria that policy makers should use in assessing responses to global warming: economic efficiency, flexibility, urgency, low cost, equity, institutional feasibility, unique or critical resources, health and safety, consistency, and private versus public sector.

Adaptation can mitigate the adverse impacts of climate change, but it will incur costs and will not prevent all damage. The IPCC points out that many adverse effects of climate change are not changes in the average conditions, but changes in the variation or the extremes of conditions. For example, the average sea level in a port might not be as important as the height of water during a storm surge (which causes flooding); the average rainfall in an area might not be as important as how frequent and severe droughts and extreme precipitation events become. Additionally, effective adaptive policy can be difficult to implement because policymakers are rewarded more for enacting short-term change, rather than long-term planning. Since the impacts of climate change are generally not seen in the short term, policymakers have less incentive to act. Furthermore, climate change is occurring on a global scale, leading to global policy and research efforts such as the Paris Agreement and research through the IPCC, creating a global framework for adapting to and combating climate change. The vast majority of climate change adaptation and mitigation policies are being implemented on a more local scale because different regions must adapt differently and because national and global policies are often more challenging to enact.

Differing time scales

Adaptation can either occur in anticipation of change (anticipatory adaptation), or be a response to those changes (reactive adaptation). Most adaptation being implemented at present is responding to current climate trends and variability, for example increased use of artificial snow-making in the European Alps. Some adaptation measures, however, are anticipating future climate change, such as the construction of the Confederation Bridge in Canada at a higher elevation to take into account the effect of future sea-level rise on ship clearance under the bridge.

Maladaptation

Much adaptation takes place in relation to short-term climate variability, however this may cause maladaptation to longer-term climatic trends. For example, the expansion of irrigation in Egypt into the Western Sinai desert after a period of higher river flows is a maladaptation when viewed in relation to the longer term projections of drying in the region. Adaptations at one scale can also create externalities at another by reducing the adaptive capacity of other actors. This is often the case when broad assessments of the costs and benefits of adaptation are examined at smaller scales and it is possible to see that whilst the adaptation may benefit some actors, it has a negative effect on others.

Traditional coping strategies

People have always adapted to climatic changes and some community coping strategies already exist, for example changing sowing times or adopting new water-saving techniques. Traditional knowledge and coping strategies must be maintained and strengthened, otherwise adaptive capacity may be weakened as local knowledge of the environment is lost. Strengthening these local techniques and building upon them also makes it more likely that adaptation strategies will be adopted, as it creates more community ownership and involvement in the process. In many cases this will not be enough to adapt to new conditions which are outside the range of those previously experienced, and new techniques will be needed. The incremental adaptations which have been implemented become insufficient as the vulnerabilities and risks of climate change increase, this causes a need for transformational adaptations which are much larger and costlier. Current development efforts are increasingly focusing on community-based climate change adaptation, seeking to enhance local knowledge, participation and ownership of adaptation strategies.

International finance

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, under Article 11, incorporates a financial mechanism to developing country parties to support them with adaptation. Until 2009, three funds existed under the UNFCCC financial mechanism. The Special Climate Change Fund (SCCF) and the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) are administered by the Global Environmental Facility. The Adaptation Fund was established a result of negotiations during COP15 and COP16 and is administered by its own Secretariat. Initially, when the Kyoto Protocol was in operation, the Adaptation Fund was financed by a 2% levy on the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM).

At the 15th Conference of the Parties to the UNFCCC (COP15), held in Copenhagen in 2009, the Copenhagen Accord was agreed in order to commit to the goal of sending $100 billion per year to developing countries in assistance for climate change mitigation and adaptation by 2020. The Green Climate Fund was created in 2010 as one of the channels for mobilizing this climate finance. As of 2020, the GCF has failed to reach its expected target, and risks a shrinkage in its funding after the US withdrew from the Paris Agreement.

Additionality

A key and defining feature of international adaptation finance is its premise on the concept of additionality. This reflects the linkages between adaptation finance and other levels of development aid. Many developed countries already provide international aid assistance to developing countries to address challenges such as poverty, malnutrition, food insecurity, availability of drinking water, indebtedness, illiteracy, unemployment, local resource conflicts, and lower technological development. Climate change threatens to exacerbate or stall progress on fixing some of these pre-existing problems, and creates new problems. To avoid existing aid being redirected, additionality refers to the extra costs of adaptation.

The four main definitions of additionality are:

- Climate finance classified as aid, but additional to (over and above) the 0.7% ODA target;

- Increase on previous year's Official Development Assistance (ODA) spent on climate change mitigation;

- Rising ODA levels that include climate change finance but where it is limited to a specified percentage; and

- Increase in climate finance not connected to ODA.

A criticism of additionality is that it encourages business as usual that does not account for the future risks of climate change. Some advocates have thus proposed integrating climate change adaptation into poverty reduction programs.

From 2010 to 2020, Denmark increased its global warming adaptation aid 33%, from 0.09% of GDP to 0.12% of GDP, but not by additionality. Instead, the aid was subtracted from other foreign assistance funds. Politiken wrote: "Climate assistance is taken from the poorest."

Interaction with mitigation

IPCC Working Group II, the United States National Academy of Sciences, the United Nations Disaster Risk Reduction Office, and other science policy experts agree that while mitigating the emission of greenhouse gases is important, adaptation to the effects of global warming will still be necessary. Some, like the UK Institution of Mechanical Engineers, worry that mitigation efforts will largely fail.

Mitigating global warming is an economic and political challenge. Given that greenhouse gas levels are already elevated, the lag of decades between emissions and some impacts, and the significant economic and political challenges of success, it is uncertain how much climate change will be mitigated.

There are some synergies and trade-offs between adaptation and mitigation. Adaptation measures often offer short-term benefits, whereas mitigation has longer-term benefits. Adaptation and mitigation have often been treated separately in research as well as in policy. For instance, compact urban development may lead to reduced transport and building greenhouse gas emissions. Simultaneously, it may increase the urban heat island effect, leading to higher temperatures and increasing exposure.

Synergies include the benefits of public transport on both mitigation and adaptation. Public transport has fewer greenhouse gas emissions per kilometer travelled than cars. A good public transport netwerk also increases resilience in case of disasters: evacuation and emergency access becomes easier. Reduced air pollution from public transport improves health, which in turn may lead to improved economic resilience, as healthy workers perform better.

After assessing the literature on sustainability and climate change, scientists concluded with high confidence that up to the year 2050, an effort to cap GHG emissions at 550 ppm would benefit developing countries significantly. This was judged to be especially the case when combined with enhanced adaptation. By 2100, however, it was still judged likely that there would be significant climate change impacts. This was judged to be the case even with aggressive mitigation and significantly enhanced adaptive capacity.