The economics of climate change concerns the economic aspects of climate change; this can inform policies that governments might consider in response. A number of factors make this and the politics of climate change a difficult problem: it is a long-term, intergenerational problem; benefits and costs are distributed unequally both within and across countries; and both scientific and public opinions need to be taken into account.

One of the most important greenhouse gases is carbon dioxide (CO

2). Around 20% of carbon dioxide which is emitted due to human activities can remain in the atmosphere for many thousands of years. The long time scales and uncertainty associated with global warming have led analysts to develop "scenarios" of future environmental, social and economic changes. These scenarios can help governments understand the potential consequences of their decisions.

The impacts of climate change include the loss of biodiversity, sea level rise, increased frequency and severity of some extreme weather events, and acidification of the oceans. Economists have attempted to quantify these impacts in monetary terms, but these assessments can be controversial. The two main policy responses to global warming are to reduce greenhouse gas emissions (climate change mitigation) and to adapt to the impacts of global warming (e.g., by building levees in response to sea level rise).

One of the responses to the uncertainties of global warming is to adopt a strategy of sequential decision making. This strategy recognizes that decisions on global warming need to be made with incomplete information, and that decisions in the near term will have potentially long-term impacts. Governments might choose to use risk management as part of their policy response to global warming. For instance, a risk-based approach can be applied to climate impacts which are difficult to quantify in economic terms, e.g., the impacts of global warming on indigenous peoples.

Analysts have assessed global warming in relation to sustainable development. Sustainable development considers how future generations might be affected by the actions of the current generation. In some areas, policies designed to address global warming may contribute positively towards other development objectives, for example abolishing fossil fuel subsidies would reduce air pollution and thus save lives. Direct global fossil fuel subsidies reached $319 billion in 2017, and $5.2 trillion when indirect costs such as air pollution are priced in. In other areas, the cost of global warming policies may divert resources away from other socially and environmentally beneficial investments (the opportunity costs of climate change policy). More recent studies suggest that economic damages due to climate change have been underestimated, and may be severe, with the probability of disastrous tail-risk events being nontrivial.

Scenarios

One of the economic aspects of climate change is producing scenarios of future economic development. Future economic developments can, for example, affect how vulnerable society is to future climate change, what the future impacts of climate change might be, as well as the level of future GHG emissions.

Emissions scenarios

In scenarios designed to project future GHG emissions, economic projections, e.g., changes in future income levels, will often necessarily be combined with other projections that affect emissions, e.g., future population levels. Since these future changes are highly uncertain, one approach is that of scenario analysis. In scenario analysis, scenarios are developed that are based on differing assumptions of future development patterns. An example of this are the "SRES" emissions scenarios produced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The SRES scenarios project a wide range of possible future emissions levels. The SRES scenarios are "baseline" or "non-intervention" scenarios, in that they assume no specific policy measures to control future GHG emissions. The different SRES scenarios contain widely differing assumptions of future social and economic changes. For example, the SRES "A2" emissions scenario projects a future population level of 15 billion people in the year 2100, but the SRES "B1" scenario projects a lower population level of 7 billion people. The SRES scenarios were not assigned probabilities by the IPCC, but some authors have argued that particular SRES scenarios are more likely to occur than others.

Some analysts have developed scenarios that project a continuation of current policies into the future. These scenarios are sometimes called "business-as-usual" scenarios.

Experts who work on scenarios tend to prefer the term "projections" to "forecasts" or "predictions". This distinction is made to emphasize the point that probabilities are not assigned to the scenarios, and that future emissions depend on decisions made both now and into the future.

Another approach is that of uncertainty analysis, where analysts attempt to estimate the probability of future changes in emission levels.

Global futures scenarios

"Global futures" scenarios can be thought of as stories of possible futures. They allow for the description of factors which are difficult to quantify but are important in affecting future GHG emissions. The IPCC Third Assessment Report (Morita et al., 2001) includes an assessment of 124 global futures scenarios. These scenarios project a wide range of possible futures. Some are pessimistic, for example, 5 scenarios project the future breakdown of human society. Others are optimistic, for example, in 5 other scenarios, future advances in technology solve most or all of humanity's problems. Most scenarios project increasing damage to the natural environment, but many scenarios also project this trend to reverse in the long-term.

In the scenarios, Morita et al. (2001) found no strong patterns in the relationship between economic activity and GHG emissions. By itself, this relationship is not proof of causation, and is only reflective of the scenarios that were assessed.

In the assessed scenarios, economic growth is compatible with increasing or decreasing GHG emissions. In the latter case, emissions growth is mediated by increased energy efficiency, shifts to non-fossil energy sources, and/or shifts to a post-industrial (service-based) economy. Most scenarios projecting rising GHGs also project low levels of government intervention in the economy. Scenarios projecting falling GHGs generally have high levels of government intervention in the economy.

Factors affecting emissions growth

2 emissions, world population, world GDP per capita, energy intensity of world GDP and carbon intensity of world energy use.

Historically, growth in GHG emissions have been driven by economic development. One way of understanding trends in GHG emissions is to use the Kaya identity. The Kaya identity breaks down emissions growth into the effects of changes in human population, economic affluence, and technology:

CO

2 emissions from energy ≡

2 emissions / energy use)

GDP per person (or "per capita")

is used as a measure of economic affluence, and changes in technology

are described by the other two terms: (energy use / GDP) and

(energy-related CO

2 emissions / energy use). These two terms are often referred to as "energy intensity of GDP" and "carbon intensity of energy", respectively. Note that the abbreviated term "carbon intensity" may also refer to the carbon intensity of GDP, i.e., (energy-related CO

2 emissions / GDP).

Reductions in the energy intensity of GDP and/or carbon intensity of energy will tend to reduce energy-related CO

2 emissions. Increases in population and/or GDP per capita will tend to increase energy-related CO

2

emissions. If, however, energy intensity of GDP or carbon intensity of

energy were reduced to zero (i.e., complete decarbonization of the

energy system), increases in population or GDP per capita would not lead

to an increase in energy-related CO

2 emissions.

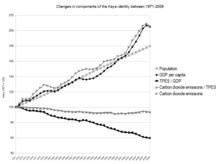

The graph on the right shows changes in global energy-related CO

2

emissions between 1971 and 2009. Also plotted are changes in world

population, world GDP per capita, energy intensity of world GDP, and

carbon intensity of world energy use. Over this time period, reductions

in energy intensity of GDP and carbon intensity of energy use have been

unable to offset increases in population and GDP per capita.

Consequently, energy-related CO

2 emissions have increased. Between 1971 and 2009, energy-related CO

2 emissions grew on average by about 2.8% per year. Population grew on average by about 2.1% per year and GDP per capita by 2.6% per year. Energy intensity of GDP on average fell by about 1.1% per year, and carbon intensity of energy fell by about 0.2% per year.

Trends and projections

Emissions

Equity and GHG emissions

In considering GHG emissions, there are a number of areas where equity is important. In common language equity means "the quality of being impartial" or "something that is fair and just." One example of the relevance of equity to GHG emissions are the different ways in which emissions can be measured. These include the total annual emissions of one country, cumulative emissions measured over long time periods (sometimes measured over more than 100 years), average emissions per person in a country (per capita emissions), as well as measurements of energy intensity of GDP, carbon intensity of GDP, or carbon intensity of energy use (discussed earlier). Different indicators of emissions provide different insights relevant to climate change policy, and have been an important issue in international climate change negotiations (e.g., see Kyoto Protocol#Negotiations).

Developed countries' past contributions to climate change were in the process of economically developing to their current level of prosperity; developing countries are attempting to rise to this level, this being one cause of their increasing greenhouse gas emissions. Equity is an issue in GHG emissions scenarios, Sonali P. Chitre argues, and Emerging markets countries, such as India and China, often would rather analyze Per capita emissions instead of committing to aggregate Emissions reduction because of historical contributions by the Industrialized nations to the climate change crisis, under the principle of Common But Differentiated Responsibilities. For example, the scenarios used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) First Assessment Report of 1990 were criticized by Parikh (1992). Parikh (1992) argued that the stabilization scenarios contained in the Report "stabilize the lifestyles of the rich and adversely affect the development of the poor". The IPCC's later "SRES" scenarios, published in 2000, explicitly explore scenarios with a narrowing income gap (convergence) between the developed and developing countries. Projections of convergence in the SRES scenarios have been criticized for lacking objectivity (Defra/HM Treasury, 2005).

Emissions projections

Changes in future greenhouse gas emission levels are highly

uncertain, and a wide range of quantitative emission projections have

been produced. Rogner et al. (2007) assessed these projections. Some of these projections aggregate anthropogenic emissions into a single figure as a "carbon dioxide equivalent" (CO

2-eq). By 2030, baseline scenarios projected an increase in greenhouse emissions (the F-gases, nitrous oxide, methane, and CO

2, measured in CO

2-eq) of between 25% and 90%, relative to the 2000 level. For CO

2

only, two-thirds to three-quarters of the increase in emissions was

projected to come from developing countries, although the average per capita CO

2 emissions in developing country regions were projected to remain substantially lower than those in developed country regions.

By 2100, CO

2-eq projections ranged from a 40% reduction to an increase in emissions of 250% above their levels in 2000.

Concentrations and temperatures

As mentioned earlier, impacts of climate change are determined more by the concentration of GHGs in the atmosphere than annual GHG emissions. Changes in the atmospheric concentrations of the individual GHGs are given in greenhouse gas.

Rogner et al. (2007) reported that the then-current estimated total atmospheric concentration of long-lived GHGs was around 455 parts-per-million (ppm) CO

2-eq (range: 433-477 ppm CO

2-eq). The effects of aerosol and land-use changes (e.g., deforestation) reduced the physical effect (the radiative forcing) of this to 311 to 435 ppm CO

2-eq, with a central estimate of about 375 ppm CO

2-eq. The 2011 estimate of CO

2-eq concentrations (the long-lived GHGs, made up of CO

2, methane (CH

4), nitrous oxide (N

2O), chlorofluorocarbon-12 (CFC-12), CFC-11, and fifteen other halogenated gases) is 473 ppm CO

2-eq (NOAA, 2012). The NOAA (2012) estimate excludes the overall cooling effect of aerosols (e.g., sulfate).

Six of the SRES emissions scenarios have been used to project possible future changes in atmospheric CO

2 concentrations. For the six illustrative SRES scenarios, IPCC (2001) projected the concentration of CO

2 in the year 2100 as ranging between 540 and 970 parts-per-million (ppm) . Uncertainties such as the removal of carbon from the atmosphere by "sinks" (e.g., forests) increase the projected range to between 490 and 1,260 ppm. This compares to a pre-industrial (taken as the year 1750) concentration of 280 ppm, and a concentration of 390.5 ppm in 2011.

Temperature

Atmospheric GHG concentrations can be related to changes in global mean temperature by the climate sensitivity. Projections of future global warming are affected by different estimates of climate sensitivity. For a given increase in the atmospheric concentration of GHGs, high estimates of climate sensitivity suggest that relatively more future warming will occur, while low estimates of climate sensitivity suggest that relatively less future warming will occur. Lower values would correspond with less severe climate impacts, while higher values would correspond with more severe impacts.

In the scientific literature, there is sometimes a focus on "best estimate" or "likely" values of climate sensitivity. However, from a risk management perspective (discussed below), values outside of "likely" ranges are relevant, because, though these values are less probable, they could be associated with more severe climate impacts (the statistical definition of risk = probability of an impact × magnitude of the impact).

Analysts have also looked at how uncertainty over climate sensitivity affects economic estimates of climate change impacts. Hope (2005), for example, found that uncertainty over the climate sensitivity was the most important factor in determining the social cost of carbon (an economic measure of climate change impacts).

Cost–benefit analysis

Standard cost–benefit analysis (CBA) (also referred to as a monetized cost–benefit framework) has been applied to the problem of climate change. This requires (1) the valuation of costs and benefits using willingness to pay (WTP) or willingness to accept (WTA) compensation as a measure of value, and (2) a criterion for accepting or rejecting proposals:

For (1), in CBA where WTP/WTA is used, climate change impacts are aggregated into a monetary value, with environmental impacts converted into consumption equivalents, and risk accounted for using certainty equivalents. Values over time are then discounted to produce their equivalent present values.

The valuation of costs and benefits of climate change can be controversial because some climate change impacts are difficult to assign a value to, e.g., ecosystems and human health. It is also impossible to know the preferences of future generations, which affects the valuation of costs and benefits. Another difficulty is quantifying the risks of future climate change.

For (2), the standard criterion is the (Kaldor-Hicks) compensation principle. According to the compensation principle, so long as those benefiting from a particular project compensate the losers, and there is still something left over, then the result is an unambiguous gain in welfare. If there are no mechanisms allowing compensation to be paid, then it is necessary to assign weights to particular individuals.

One of the mechanisms for compensation is impossible for this problem: mitigation might benefit future generations at the expense of current generations, but there is no way that future generations can compensate current generations for the costs of mitigation. On the other hand, should future generations bear most of the costs of climate change, compensation to them would not be possible. Another transfer for compensation exists between regions and populations. If, for example, some countries were to benefit from future climate change but others lose out, there is no guarantee that the winners would compensate the losers; similarly, if some countries were to benefit from reducing climate change but others lose out, there would likewise be no guarantee that the winners would compensate the losers.

Cost–benefit analysis and risk

In a cost–benefit analysis, an acceptable risk means that the benefits of a climate policy outweigh the costs of the policy. The standard rule used by public and private decision makers is that a risk will be acceptable if the expected net present value is positive. The expected value is the mean of the distribution of expected outcomes. In other words, it is the average expected outcome for a particular decision. This criterion has been justified on the basis that:

- a policy's benefits and costs have known probabilities

- economic agents (people and organizations) can diversify their own risk through insurance and other markets.

On the first point, probabilities for climate change are difficult to calculate. Although some impacts, such as those on human health and biodiversity, are difficult to value it has been estimated that 3.5 million people die prematurely each year from air pollution from fossil fuels. The health benefits of meeting climate goals substantially outweigh the costs of action. According to Professor Sir Andy Haines at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine the health benefits of phasing out fossil fuels measured in money (estimated by economists using the value of life for each country) are substantially more than the cost of achieving the 2 degree C goal of the Paris Agreement.

On the second point, it has been suggested that insurance could be bought against climate change risks. In practice, however, there are difficulties in implementing the necessary policies to diversify climate change risks.

Risk

2, emissions worldwide would need to be dramatically reduced from their present level.

One of the problems of climate change are the large uncertainties over the potential impacts of climate change, and the costs and benefits of actions taken in response to climate change, e.g., in reducing GHG emissions. Two related ways of thinking about the problem of climate change decision-making in the presence of uncertainty are iterative risk management and sequential decision making. Considerations in a risk-based approach might include, for example, the potential for low-probability, worst-case climate change impacts.

An approach based on sequential decision making recognises that,

over time, decisions related to climate change can be revised in the

light of improved information. This is particularly important with respect to climate change, due to the long-term nature of the problem. A near-term hedging strategy concerned with reducing future climate impacts might favour stringent, near-term emissions reductions. As stated earlier, carbon dioxide accumulates in the atmosphere, and to stabilize the atmospheric concentration of CO

2, emissions would need to be drastically reduced from their present level (refer to diagram opposite).

Stringent near-term emissions reductions allow for greater future

flexibility with regard to a low stabilization target, e.g., 450 parts-per-million (ppm) CO

2. To put it differently, stringent near-term emissions abatement can be seen as having an option value

in allowing for lower, long-term stabilization targets. This option may

be lost if near-term emissions abatement is less stringent.

On the other hand, a view may be taken that points to the benefits of improved information over time. This may suggest an approach where near-term emissions abatement is more modest. Another way of viewing the problem is to look at the potential irreversibility of future climate change impacts (e.g., damages to ecosystems) against the irreversibility of making investments in efforts to reduce emissions (see also Economics of climate change mitigation#Irreversible impacts and policy). Overall, a range of arguments can be made in favour of policies where emissions are reduced stringently or modestly in the near-term.

Resilient and adaptive strategies

Granger Morgan et al. (2009) suggested two related decision-making management strategies that might be particularly appealing when faced with high uncertainty. The first were resilient strategies. This seeks to identify a range of possible future circumstances, and then choose approaches that work reasonably well across all the range. The second were adaptive strategies. The idea here is to choose strategies that can be improved as more is learned as the future progresses. Granger Morgan et al. (2009) contrasted these two approaches with the cost–benefit approach, which seeks to find an optimal strategy.

Portfolio theory

An example of a strategy that is based on risk is portfolio theory. This suggests that a reasonable response to uncertainty is to have a wide portfolio of possible responses. In the case of climate change, mitigation can be viewed as an effort to reduce the chance of climate change impacts (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 24). Adaptation acts as insurance against the chance that unfavourable impacts occur. The risk associated with these impacts can also be spread. As part of a policy portfolio, climate research can help when making future decisions. Technology research can help to lower future costs.

Optimal choices and risk aversion

The optimal result of decision analysis depends on how "optimal" is defined (Arrow et al., 1996. See also the section on trade offs). Decision analysis requires a selection criterion to be specified. In a decision analysis based on monetized cost–benefit analysis (CBA), the optimal policy is evaluated in economic terms. The optimal result of monetized CBA maximizes net benefits. Another type of decision analysis is cost-effectiveness analysis. Cost-effectiveness analysis aims to minimize net costs.

Monetized CBA may be used to decide on the policy objective, e.g., how much emissions should be allowed to grow over time. The benefits of emissions reductions are included as part of the assessment.

Unlike monetized CBA, cost-effectiveness analysis does not suggest an optimal climate policy. For example, cost-effectiveness analysis may be used to determine how to stabilize atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations at lowest cost. However, the actual choice of stabilization target (e.g., 450 or 550 ppm carbon dioxide equivalent), is not "decided" in the analysis.

The choice of selection criterion for decision analysis is subjective. The choice of criterion is made outside of the analysis (it is exogenous). One of the influences on this choice on this is attitude to risk. Risk aversion describes how willing or unwilling someone is to take risks. Evidence indicates that most, but not all, individuals prefer certain outcomes to uncertain ones. Risk-averse individuals prefer decision criteria that reduce the chance of the worst possible outcome, while risk-seeking individuals prefer decision criteria that maximize the chance of the best possible outcome. In terms of returns on investment, if society as a whole is risk-averse, we might be willing to accept some investments with negative expected returns, e.g., in mitigation. Such investments may help to reduce the possibility of future climate damages or the costs of adaptation.

Alternative views

As stated, there is considerable uncertainty over decisions regarding climate change, as well as different attitudes over how to proceed, e.g., attitudes to risk and valuation of climate change impacts. Risk management can be used to evaluate policy decisions based a range of criteria or viewpoints, and is not restricted to the results of particular type of analysis, e.g., monetized CBA. Some authors have focused on a disaggregated analysis of climate change impacts. "Disaggregated" refers to the choice to assess impacts in a variety of indicators or units, e.g., changes in agricultural yields and loss of biodiversity. By contrast, monetized CBA converts all impacts into a common unit (money), which is used to assess changes in social welfare.

International insurance

Traditional insurance works by transferring risk to those better able or more willing to bear risk, and also by the pooling of risk (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 25). Since the risks of climate change are, to some extent, correlated, this reduces the effectiveness of pooling. However, there is reason to believe that different regions will be affected differently by climate change. This suggests that pooling might be effective. Since developing countries appear to be potentially most at risk from the effects of climate change, developed countries could provide insurance against these risks.

A study carried out by David R. Easterling et al. identified societal impacts in the United States. Losses caused by catastrophes, defined by the property insurance industry as storms causing insured losses over $5 million in the year of occurrence, have grown steadily in the United States from about $100 million annually in the 1950s to $6 billion per year in the 1990s, and the annual number of catastrophes grew from 10 in the 1950s to 35 in the 1990s.”

Authors have pointed to several reasons why commercial insurance markets cannot adequately cover risks associated with climate change (Arrow et al., 1996, p. 72). For example, there is no international market where individuals or countries can insure themselves against losses from climate change or related climate change policies.

Financial markets for risk

There are several options for how insurance could be used in responding to climate change (Arrow et al., 1996, p. 72). One response could be to have binding agreements between countries. Countries suffering greater-than-average climate-related losses would be assisted by those suffering less-than-average losses. This would be a type of mutual insurance contract. Another approach would be to trade "risk securities" among countries. These securities would amount to betting on particular climate outcomes.

These two approaches would allow for a more efficient distribution of climate change risks. They would also allow for different beliefs over future climate outcomes. For example, it has been suggested that these markets might provide an objective test of the honesty of a particular country's beliefs over climate change. Countries that honestly believe that climate change presents little risk would be more prone to hold securities against these risks.

Impacts

Adaptation and vulnerability

IPCC (2007a) defined adaptation (to climate change) as "[initiatives] and measures to reduce the vulnerability of natural and human systems against actual or expected climate change effects" (p. 76). Vulnerability (to climate change) was defined as "the degree to which a system is susceptible to, and unable to cope with, adverse effects of climate change, including climate variability and extremes" (p. 89).

Autonomous and planned adaptation

Autonomous adaptation are adaptations that are reactive to climatic stimuli, and are done as a matter of course without the intervention of a public agency. Planned adaptation can be reactive or anticipatory, i.e., undertaken before impacts are apparent. Some studies suggest that human systems have considerable capacity to adapt autonomously (Smit et al., 2001:890). Others point to constraints on autonomous adaptation, such as limited information and access to resources (p. 890). Smit et al. (2001:904) concluded that relying on autonomous adaptation to climate change would result in substantial ecological, social, and economic costs. In their view, these costs could largely be avoided with planned adaptation.

Costs and benefits

A literature assessment by Adger et al. (2007:719) concluded that there was a lack of comprehensive, global cost and benefit estimates for adaptation. Studies were noted that provided cost estimates of adaptation at regional level, e.g., for sea-level rise. A number of adaptation measures were identified as having high benefit-cost ratios.

Adaptive capacity

Adaptive capacity is the ability of a system to adjust to climate change. Smit et al. (2001:895–897) described the determinants of adaptive capacity:

- Economic resources: Wealthier nations are better able to bear the costs of adaptation to climate change than poorer ones.

- Technology: Lack of technology can impede adaptation.

- Information and skills: Information and trained personnel are required to assess and implement successful adaptation options.

- Social infrastructure

- Institutions: Nations with well-developed social institutions are believed to have greater adaptive capacity than those with less effective institutions, typically developing nations and economies in transition.

- Equity: Some believe that adaptive capacity is greater where there are government institutions and arrangements in place that allow equitable access to resources.

Smit et al. (2001) concluded that:

- countries with limited economic resources, low levels of technology, poor information and skills, poor infrastructure, unstable or weak institutions, and inequitable empowerment and access to resources have little adaptive capacity and are highly vulnerable to climate change (p. 879).

- developed nations, broadly speaking, have greater adaptive capacity than developing regions or countries in economic transition (p. 897).

Enhancing adaptive capacity

Smit et al. (2001:905) concluded that enhanced adaptive capacity would reduce vulnerability to climate change. In their view, activities that enhance adaptive capacity are essentially equivalent to activities that promote sustainable development. These activities include (p. 899):

- improving access to resources

- reducing poverty

- lowering inequities of resources and wealth among groups

- improving education and information

- improving infrastructure

- improving institutional capacity and efficiency

Goklany (1995) concluded that promoting free trade – e.g., through the removal of international trade barriers – could enhance adaptive capacity and contribute to economic growth.

Regions

With high confidence, Smith et al. (2001:957–958) concluded that developing countries would tend to be more vulnerable to climate change than developed countries. Based on then-current development trends, Smith et al. (2001:940–941) predicted that few developing countries would have the capacity to efficiently adapt to climate change.

- Africa: In a literature assessment, Boko et al. (2007:435) concluded, with high confidence, that Africa's major economic sectors had been vulnerable to observed climate variability. This vulnerability was judged to have contributed to Africa's weak adaptive capacity, resulting in Africa having high vulnerability to future climate change. It was thought likely that projected sea-level rise would increase the socio-economic vulnerability of African coastal cities.

- Asia: Lal et al. (2001:536) reviewed the literature on adaptation and vulnerability. With medium confidence, they concluded that climate change would result in the degradation of permafrost in boreal Asia, worsening the vulnerability of climate-dependent sectors, and affecting the region's economy.

- Australia and New Zealand: Hennessy et al. (2007:509) reviewed the literature on adaptation and vulnerability. With high confidence, they concluded that in Australia and New Zealand, most human systems had considerable adaptive capacity. With medium confidence, some Indigenous communities were judged to have low adaptive capacity.

- Europe: In a literature assessment, Kundzewicz et al. (2001:643) concluded, with very high confidence, that the adaptation potential of socioeconomic systems in Europe was relatively high. This was attributed to Europe's high GNP, stable growth, stable population, and well-developed political, institutional, and technological support systems.

- Latin America: In a literature assessment, Mata et al. (2001:697) concluded that the adaptive capacity of socioeconomic systems in Latin America was very low, particularly in regard to extreme weather events, and that the region's vulnerability was high.

- Polar regions: Anisimov et al. (2001, pp. 804–805) concluded that:

- within the Antarctic and Arctic, at localities where water was close to melting point, socioeconomic systems were particularly vulnerable to climate change.

- the Arctic would be extremely vulnerable to climate change. Anisimov et al. (2001) predicted that there would be major ecological, sociological, and economic impacts in the region.

- Small islands: Mimura et al. (2007, p. 689) concluded, with very high confidence, that small islands were particularly vulnerable to climate change. Partly this was attributed to their low adaptive capacity and the high costs of adaptation in proportion to their GDP.

Systems and sectors

- Coasts and low-lying areas: According to Nicholls et al. (2007, p. 336), societal vulnerability to climate change is largely dependent on development status. Developing countries lack the necessary financial resources to relocate those living in low-lying coastal zones, making them more vulnerable to climate change than developed countries. With high confidence, Nicholls et al. (2007, p. 317) concluded that on vulnerable coasts, the costs of adapting to climate change are lower than the potential damage costs.

- Industry, settlements and society:

- At the scale of a large nation or region, at least in most industrialized economies, the economic value of sectors with low vulnerability to climate change greatly exceeds that of sectors with high vulnerability (Wilbanks et al., 2007, p. 366). Additionally, the capacity of a large, complex economy to absorb climate-related impacts, is often considerable. Consequently, estimates of the aggregate damages of climate change – ignoring possible abrupt climate change – are often rather small as a percentage of economic production. On the other hand, at smaller scales, e.g., for a small country, sectors and societies might be highly vulnerable to climate change. Potential climate change impacts might therefore amount to very severe damages.

- Wilbanks et al. (2007, p. 359) concluded, with very high confidence, that vulnerability to climate change depends considerably on specific geographic, sectoral and social contexts. In their view, these vulnerabilities are not reliably estimated by large-scale aggregate modelling.

Mitigation

Mitigation of climate change involves actions that are designed to limit the amount of long-term climate change (Fisher et al., 2007:225). Mitigation may be achieved through the reduction of GHG emissions or through the enhancement of sinks that absorb GHGs, e.g., forests.

International public goods

The atmosphere is an international public good, and GHG emissions are an international externality (Goldemberg et al., 1996:21, 28, 43). A change in the quality of the atmosphere does not affect the welfare of all individuals equally. In other words, some individuals may benefit from climate change, while others may lose out. This uneven distribution of potential climate change impacts, plus the uneven distribution of emissions globally, make it difficult to secure a global agreement to reduce emissions (Halsnæs et al., 2007:127).

Policies

National

Both climate and non-climate policies can affect emissions growth. Non-climate policies that can affect emissions are listed below (Bashmakov et al., 2001:409-410):

- Market-orientated reforms can have important impacts on energy use, energy efficiency, and therefore GHG emissions.

- Price and subsidy policies: Many countries provide subsidies for activities that impact emissions, e.g., subsidies in the agriculture and energy sectors, and indirect subsidies for transport.

- Market liberalization: Restructuring of energy markets has occurred in several countries and regions. These policies have mainly been designed to increase competition in the market, but they can have a significant impact on emissions.

There are a number of policies that might be used to mitigate climate change, including *The Green Marshall Plan (http://nb.referata.com/w/index.php?title=Green_Marshall_Plan&action=edit) which calls for global central bank money creation to fund green infrastructure, (Bashmakov et al., 2001:412–422):

- Regulatory standards, such as fuel-efficiency standards for cars (Creutzig et al., 2011).

- Market-based instruments, such as emissions taxes and tradable permits.

- Voluntary agreements between public agencies and industry.

- Informational instruments, e.g., to increase public awareness of climate change.

- Use of subsidies and financial incentives, e.g., feed-in tariffs for renewable energy (Gupta et al., 2007:762).

- Removal of subsidies, e.g., for coal mining and burning (Barker et al., 2001:567–568).

- Demand-side management, which aims to reduce energy demand through energy audits, product labelling, etc.

International

- The Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC sets out legally binding emission reduction commitments for the "Annex B" countries (Verbruggen, 2007, p. 817). The Protocol defines three international policy instruments ("Flexibility Mechanisms") which can be used by the Annex B countries to meet their emission reduction commitments. According to Bashmakov et al. (2001:402), use of these instruments could significantly reduce the costs for Annex B countries in meeting their emission reduction commitments.

- Other possible policies include internationally coordinated carbon taxes and/or regulation (Bashmakov et al., 2001:430).

Finance

The International Energy Agency estimates that US$197 billion is required by states in the developing world above and beyond the underlying investments needed by various sectors regardless of climate considerations, this is twice the amount promised by the developed world at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Cancún Agreements. Thus, a new method is being developed to help ensure that funding is available for climate change mitigation. This involves financial leveraging, whereby public financing is used to encourage private investment.

Cost estimates

According to a literature assessment by Barker et al. (2007b:622), mitigation cost estimates depend critically on the baseline (in this case, a reference scenario that the alternative scenario is compared with), the way costs are modelled, and assumptions about future government policy. Fisher et al. (2007:204–206) (summarized by IPCC, 2007b:11) estimated macroeconomic costs in 2030 for multi-gas mitigation (reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other GHGs, such as methane) as between a 3% decrease in global GDP to a small increase, relative to baseline. This was for an emissions pathway consistent with atmospheric stabilization of GHGs between 445 and 710 ppm CO2-eq. In 2050, the estimated costs for stabilization between 710 and 445 ppm CO2-eq ranged between a 1% gain to a 5.5% decrease in global GDP, relative to baseline. These cost estimates were supported by a moderate amount of evidence and much agreement in the literature (IPCC, 2007b:11,18).

Macroeconomic cost estimates made by Fisher et al. (2007:204) were mostly based on models that assumed transparent markets, no transaction costs, and perfect implementation of cost-effective policy measures across all regions throughout the 21st century. According to Fisher et al. (2007), relaxation of some or all these assumptions would lead to an appreciable increase in cost estimates. On the other hand, IPCC (2007b:8) noted that cost estimates could be reduced by allowing for accelerated technological learning, or the possible use of carbon tax/emission permit revenues to reform national tax systems.

- Regional costs were estimated as possibly being significantly different from the global average. Regional costs were found to be largely dependent on the assumed stabilization level and baseline scenario.

- Sectoral costs: In a literature assessment, Barker et al. (2001:563–564), predicted that the renewables sector could potentially benefit from mitigation. The coal (and possibly the oil) industry was predicted to potentially lose substantial proportions of output relative to a baseline scenario, with energy-intensive sectors, such as heavy chemicals, facing higher costs.

One 2020 study estimated economic losses due to climate change could be between 127 and 616 trillion dollars extra until 2100 with current commitments, compared to 1.5 °C or well below 2 °C compatible action action. Failure to implement current commitments raises economic losses to 150–792 trillion dollars until 2100. In this study, mitigation was achieved by countries optimising their own economy.

Adaptation and mitigation

The distribution of benefits from adaptation and mitigation policies are different in terms of damages avoided (Toth et al., 2001:653). Adaptation activities mainly benefit those who implement them, while mitigation benefits others who may not have made mitigation investments. Mitigation can therefore be viewed as a global public good, while adaptation is either a private good in the case of autonomous adaptation, or a national or regional public good in the case of public sector policies.

Paying for an international public good

Economists generally agree on the following two principles (Goldemberg, et al.., 1996:29):

- For the purposes of analysis, it is possible to separate equity from efficiency. This implies that all emitters, regardless of whether they are rich or poor, should pay the full social costs of their actions. From this perspective, corrective (Pigouvian) taxes should be applied uniformly (see carbon tax#Economic theory). It has been suggested that countries over the average per person emissions be carbon taxed and the funds raised given to countries under the average.

- It is inappropriate to redress all equity issues through climate change policies. However, climate change itself should not aggravate existing inequalities between different regions.

Some early studies suggested that a uniform carbon tax would be a fair and efficient way of reducing emissions (Banuri et al., 1996, pp. 103–104). A carbon tax is a Pigouvian tax, and taxes fuels based on their carbon content (Hoeller and Wallin, 1991, p. 92). A literature assessment by Banuri et al. (1996:103–104) summarized criticisms of such a system:

- A carbon tax would impose different burdens on countries due to existing differences in tax structures, resource endowments, and development.

- Most observers argue that such a tax would not be fair because of differences in historical emissions and current wealth.

- A uniform carbon tax would not be Pareto efficient unless lump sum transfers were made between countries. Pareto efficiency requires that the carbon tax would not make any countries worse off than they would be without the tax (Chichilnisky and Heal, 1994, p. 445; Tol, 2001, p. 72). Also, at least one country would need to be better off.

An alternative approach to having a Pigouvian tax is one based on property rights. A practical example of this would be a system of emissions trading, which is essentially a privatization of the atmosphere (Hepburn, 2007). The idea of using property rights in response to an externality was put forward by Coase (1960). Coase's model of social cost assumes a situation of equal bargaining power among participants and equal costs of making the bargain (Toth et al.., 2001:668). Assigning property rights can be an efficient solution. This is based on the assumption that there are no bargaining/transaction costs involved in buying or selling these property rights, and that buyers and sellers have perfect information available when making their decisions.

If these assumptions are correct, efficiency is achieved regardless of how property rights are allocated. In the case of emissions trading, this suggests that equity and efficiency can be addressed separately: equity is taken care of in the allocation of emission permits, and efficiency is promoted by the market system. In reality, however, markets do not live up to the ideal conditions that are assumed in Coase's model, with the result that there may be trade-offs between efficiency and equity (Halsnæs et al., 2007).

Efficiency and equity

No scientific consensus exists on who should bear the burden of adaptation and mitigation costs (Goldemberg et al.., 1996:29). Several different arguments have been made over how to spread the costs and benefits of taxes or systems based on emissions trading.

One approach considers the problem from the perspective of who benefits most from the public good. This approach is sensitive to the fact that different preferences exist between different income classes. The public good is viewed in a similar way as a private good, where those who use the public good must pay for it. Some people will benefit more from the public good than others, thus creating inequalities in the absence of benefit taxes. A difficulty with public goods is determining who exactly benefits from the public good, although some estimates of the distribution of the costs and benefits of global warming have been made – see above. Additionally, this approach does not provide guidance as to how the surplus of benefits from climate policy should be shared.

A second approach has been suggested based on economics and the social welfare function. To calculate the social welfare function requires an aggregation of the impacts of climate change policies and climate change itself across all affected individuals. This calculation involves a number of complexities and controversial equity issues (Markandya et al., 2001:460). For example, the monetization of certain impacts on human health. There is also controversy over the issue of benefits affecting one individual offsetting negative impacts on another (Smith et al.., 2001:958). These issues to do with equity and aggregation cannot be fully resolved by economics (Banuri et al.., 1996:87).

On a utilitarian basis, which has traditionally been used in welfare economics, an argument can be made for richer countries taking on most of the burdens of mitigation (Halsnæs et al., 2007). However, another result is possible with a different modeling of impacts. If an approach is taken where the interests of poorer people have lower weighting, the result is that there is a much weaker argument in favour of mitigation action in rich countries. Valuing climate change impacts in poorer countries less than domestic climate change impacts (both in terms of policy and the impacts of climate change) would be consistent with observed spending in rich countries on foreign aid (Hepburn, 2005; Helm, 2008:229).

In terms of the social welfare function, the different results depend on the elasticity of marginal utility. A declining marginal utility of consumption means that a poor person is judged to benefit more from increases in consumption relative to a richer person. A constant marginal utility of consumption does not make this distinction, and leads to the result that richer countries should mitigate less.

A third approach looks at the problem from the perspective of who has contributed most to the problem. Because the industrialized countries have contributed more than two-thirds of the stock of human-induced GHGs in the atmosphere, this approach suggests that they should bear the largest share of the costs. This stock of emissions has been described as an "environmental debt" (Munasinghe et al., 1996, p. 167). In terms of efficiency, this view is not supported. This is because efficiency requires incentives to be forward-looking, and not retrospective (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 29). The question of historical responsibility is a matter of ethics. Munasinghe et al. (1996, p. 167) suggested that developed countries could address the issue by making side-payments to developing countries.

Trade offs

It is often argued in the literature that there is a trade-off between adaptation and mitigation, in that the resources committed to one are not available for the other (Schneider et al., 2001:94). This is debatable in practice because the people who bear emission reduction costs or benefits are often different from those who pay or benefit from adaptation measures.

There is also a trade off in how much damage from climate change should be avoided. The assumption that it is always possible to trade off different outcomes is viewed as problematic by many people (Halsnæs et al., 2007). For example, a trade off might exist between economic growth and damages faced by indigenous cultures.

Some of the literature has pointed to difficulties in these kinds of assumptions. For instance, there may be aversion at any price towards losing particular species. It has also been suggested that low-probability, extreme outcomes are overweighted when making choices. This is related to climate change, since the possibility of future abrupt changes in the climate or the Earth system cannot be ruled out. For example, if the West Antarctic ice sheet was to disintegrate, it could result in a sea level rise of 4–6 meters over several centuries.

Cost–benefit analysis

In a cost–benefit analysis, the trade offs between climate change impacts, adaptation, and mitigation are made explicit. Cost–benefit analyses of climate change are produced using integrated assessment models (IAMs), which incorporate aspects of the natural, social, and economic sciences.

In an IAM designed for cost–benefit analysis, the costs and benefits of impacts, adaptation and mitigation are converted into monetary estimates. Some view the monetization of costs and benefits as controversial (see Economic impacts of climate change#Aggregate impacts). The "optimal" levels of mitigation and adaptation are then resolved by comparing the marginal costs of action with the marginal benefits of avoided climate change damages (Toth et al., 2001:654). The decision over what "optimal" is depends on subjective value judgements made by the author of the study (Azar, 1998).

There are many uncertainties that affect cost–benefit analysis, for example, sector- and country-specific damage functions (Toth et al., 2001:654). Another example is with adaptation. The options and costs for adaptation are largely unknown, especially in developing countries.

Results

A common finding of cost–benefit analysis is that the optimum level of emissions reduction is modest in the near-term, with more stringent abatement in the longer-term (Stern, 2007:298; Heal, 2008:20; Barker, 2008). This approach might lead to a warming of more than 3 °C above the pre-industrial level (World Bank, 2010:8). In most models, benefits exceed costs for stabilization of GHGs leading to warming of 2.5 °C. No models suggest that the optimal policy is to do nothing, i.e., allow "business-as-usual" emissions.

Along the efficient emission path calculated by Nordhaus and Boyer (2000) (referred to by Fisher et al.., 2007), the long-run global average temperature after 500 years increases by 6.2 °C above the 1900 level. Nordhaus and Boyer (2000) stated their concern over the potentially large and uncertain impacts of such a large environmental change. The projected temperature in this IAM, like any other, is subject to scientific uncertainty (e.g., the relationship between concentrations of GHGs and global mean temperature, which is called the climate sensitivity). Projections of future atmospheric concentrations based on emission pathways are also affected by scientific uncertainties, e.g., over how carbon sinks, such as forests, will be affected by future climate change. Klein et al. (2007) concluded that there were few high quality studies in this area, and placed low confidence in the results of cost–benefit analysis.

Hof et al. (2008) (referred to by World Bank, 2010:8) examined the sensitivity of the optimal climate target to assumptions about the time horizon, climate sensitivity, mitigation costs, likely damages, and discount rates. The optimal target was defined as the concentration that would result in the lowest reduction in the present value (i.e., discounted) of global consumption. A set of assumptions that included a relatively high climate sensitivity (i.e., a relatively large global temperature increase for a given increase in GHGs), high damages, a long time horizon, low discount rates (i.e., future consumption is valued relatively highly), and low mitigation costs, produced an optimum peak in the concentration of CO2e at 540 parts per million (ppm). Another set of assumptions that assumed a lower climate sensitivity (lower global temperature increase), lower damages, a shorter time horizon, and a higher discount rate (present consumption is valued relatively more highly), produced an optimum peaking at 750 ppm.

Strengths

In spite of various uncertainties or possible criticisms of cost–benefit analysis, it does have several strengths:

- It offers an internally consistent and global comprehensive analysis of impacts (Smith et al., 2001:955).

- Sensitivity analysis allows critical assumptions in the analysis to be changed. This can identify areas where the value of information is highest and where additional research might have the highest payoffs (Downing, et al., 2001:119).

- As uncertainty is reduced, the integrated models used in producing cost–benefit analysis might become more realistic and useful.

Geoengineering

Geoengineering are technological efforts to stabilize the climate system by direct intervention in the Earth-atmosphere-system's energy balance (Verbruggen, 2007, p. 815). The intent of geoengineering is to reduce the amount of global warming (the observed trend of increased global average temperature (NRC, 2008, p. 2)). IPCC (2007b:15) concluded that reliable cost estimates for geoengineering options had not been published. This finding was based on medium agreement in the literature and limited evidence.

Major reports considering economics of climate change

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has produced several reports where the economics literature on climate change is assessed. In 1995, the IPCC produced its second set of assessment reports on climate change. Working Group III of the IPCC produced a report on the "Economic and Social Dimensions of Climate Change." In the later third and fourth IPCC assessments, published in 2001 and 2007 respectively, the assessment of the economics literature is divided across two reports produced by IPCC Working Groups II and III. In 2011 IPCC Working Group III published a Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation.

The Stern Review on the Economics of Climate Change is a 700-page report released for the British government on 30 October 2006, by economist Nicholas Stern, chair of the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics. The report discusses the effect of global warming on the world economy.

The Garnaut Climate Change Review was a study by Professor Ross Garnaut, commissioned by then Opposition Leader, Kevin Rudd and by the Australian State and Territory Governments on 30 April 2007. After his election on 24 November 2007 Prime Minister of Australia Kevin Rudd confirmed the participation of the Commonwealth Government in the Review.

A report by the United Nations Environment Program and the World Trade Organization "provides an overview of the key linkages between trade and climate change based on a review of available literature and a survey of relevant national policies".

In 2020, the Commodity Futures Trading Commission

released a report warning that the consequences of climate change could

create chaos in the financial system and disrupt the American economy.