|

| ||||||||||

|

|

| |||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||

Nine dwarf planets with their year of discovery:

| |||||||||||

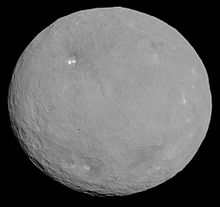

A dwarf planet is a small planetary-mass object that is in direct orbit of the Sun – something smaller than any of the eight classical planets, but still a world in its own right. The prototypical dwarf planet is Pluto. The interest of dwarf planets to planetary geologists is that, being possibly differentiated and geologically active bodies, they may display planetary geology, an expectation borne out by the Dawn mission to Ceres and the New Horizons mission to Pluto in 2015.

Counts of the number of dwarf planets among known bodies of the Solar System range from 5-and-counting (the IAU) to over 120 (Runyon et al). Apart from Sedna, the largest of these candidates have either been visited by spacecraft (Pluto and Ceres) or have at least one known moon (Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, Orcus, Salacia), which allows their masses and thus an estimate of their densities to be determined. Mass and density in turn can be fit into geophysical models in an attempt to determine the nature of these worlds.

The term dwarf planet was coined by planetary scientist Alan Stern as part of a three-way categorization of planetary-mass objects in the Solar System: classical planets, dwarf planets and satellite planets. Dwarf planets were thus conceived of as a category of planet. However, in 2006 the concept was adopted by the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as a category of sub-planetary objects, part of a three-way recategorization of bodies orbiting the Sun. Thus Stern and other planetary geologists consider dwarf planets to be planets, but since 2006 the IAU and perhaps the majority of astronomers have excluded them from the roster of planets.

History of the concept

Starting in 1801, astronomers discovered Ceres and other bodies between Mars and Jupiter that for decades were considered to be planets. Between then and around 1851, when the number of planets had reached 23, astronomers started using the word asteroid for the smaller bodies and then stopped naming or classifying them as planets.

With the discovery of Pluto in 1930, most astronomers considered the Solar System to have nine planets, along with thousands of significantly smaller bodies (asteroids and comets). For almost 50 years Pluto was thought to be larger than Mercury, but with the discovery in 1978 of Pluto's moon Charon, it became possible to measure Pluto's mass accurately and to determine that it was much smaller than initial estimates. It was roughly one-twentieth the mass of Mercury, which made Pluto by far the smallest planet. Although it was still more than ten times as massive as the largest object in the asteroid belt, Ceres, it had only one-fifth the mass of Earth's Moon. Furthermore, having some unusual characteristics, such as large orbital eccentricity and a high orbital inclination, it became evident that it was a different kind of body from any of the other planets.

In the 1990s, astronomers began to find objects in the same region of space as Pluto (now known as the Kuiper belt), and some even farther away. Many of these shared several of Pluto's key orbital characteristics, and Pluto started being seen as the largest member of a new class of objects, the plutinos. It became clear that either the larger of these bodies would also have to be classified as planets, or Pluto would have to be reclassified, much as Ceres had been reclassified after the discovery of additional asteroids. This led some astronomers to stop referring to Pluto as a planet. Several terms, including subplanet and planetoid, started to be used for the bodies now known as dwarf planets. Astronomers were also confident that more objects as large as Pluto would be discovered, and the number of planets would start growing quickly if Pluto were to remain classified as a planet.

Eris (then known as 2003 UB313) was discovered in January 2005; it was thought to be slightly larger than Pluto, and some reports informally referred to it as the tenth planet. As a consequence, the issue became a matter of intense debate during the IAU General Assembly in August 2006. The IAU's initial draft proposal included Charon, Eris, and Ceres in the list of planets. After many astronomers objected to this proposal, an alternative was drawn up by the Uruguayan astronomers Julio Ángel Fernández and Gonzalo Tancredi: they proposed an intermediate category for objects large enough to be round but which had not cleared their orbits of planetesimals. Dropping Charon from the list, the new proposal also removed Pluto, Ceres, and Eris, because they have not cleared their orbits.

Although concerns were raised about the classification of planets orbiting other stars, the issue was not resolved; it was proposed instead to decide this only when dwarf-planet-size objects start to be observed.

In the immediate aftermath of the IAU definition of dwarf planet, some scientists expressed their disagreement with the IAU resolution. Campaigns included car bumper stickers and T-shirts. Mike Brown (the discoverer of Eris) agrees with the reduction of the number of planets to eight.

NASA announced in 2006 that it would use the new guidelines established by the IAU. Alan Stern, the director of NASA's mission to Pluto, rejects the current IAU definition of planet, both in terms of defining dwarf planets as something other than a type of planet, and in using orbital characteristics (rather than intrinsic characteristics) of objects to define them as dwarf planets. Thus, in 2011, he still referred to Pluto as a planet, and accepted other likely dwarf planets such as Ceres and Eris, as well as the larger moons, as additional planets. Several years before the IAU definition, he used orbital characteristics to separate "überplanets" (the dominant eight) from "unterplanets" (the dwarf planets), considering both types "planets".

Name

Names for large subplanetary bodies include dwarf planet, planetoid, meso-planet, quasi-planet and (in the transneptunian region) plutoid. Dwarf planet, however, was originally coined as a term for the smallest planets, not the largest sub-planets, and is still used that way by many planetary astronomers.

Alan Stern coined the term dwarf planet, analogous to the term dwarf star, as part of a three-fold classification of planets, and he and many of his colleagues continue to classify dwarf planets as a class of planets. The IAU decided that dwarf planets are not to be considered planets, but kept Stern's term for them. Other terms for the IAU definition of the largest subplanetary bodies that do not have such conflicting connotations or usage include quasi-planet and the older term planetoid ("having the form of a planet"). Michael E. Brown stated that planetoid is "a perfectly good word" that has been used for these bodies for years, and that the use of the term dwarf planet for a non-planet is "dumb", but that it was motivated by an attempt by the IAU division III plenary session to reinstate Pluto as a planet in a second resolution. Indeed, the draft of Resolution 5A had called these median bodies planetoids, but the plenary session voted unanimously to change the name to dwarf planet. The second resolution, 5B, defined dwarf planets as a subtype of planet, as Stern had originally intended, distinguished from the other eight that were to be called "classical planets". Under this arrangement, the twelve planets of the rejected proposal were to be preserved in a distinction between eight classical planets and four dwarf planets. Resolution 5B was defeated in the same session that 5A was passed. Because of the semantic inconsistency of a dwarf planet not being a planet due to the failure of Resolution 5B, alternative terms such as nanoplanet and subplanet were discussed, but there was no consensus among the CSBN to change it.

In most languages equivalent terms have been created by translating dwarf planet more-or-less literally: French planète naine, Spanish planeta enano, German Zwergplanet, Russian karlikovaya planeta (карликовая планета), Arabic kaukab qazm (كوكب قزم), Chinese ǎixíngxīng (矮行星), Korean waesohangseong (왜소행성 / 矮小行星) or waehangseong (왜행성 / 矮行星), but in Japanese they are called junwakusei (準惑星), meaning "quasi-planets" or "peneplanets".

IAU Resolution 6a of 2006 recognizes Pluto as "the prototype of a new category of trans-Neptunian objects". The name and precise nature of this category were not specified but left for the IAU to establish at a later date; in the debate leading up to the resolution, the members of the category were variously referred to as plutons and plutonian objects but neither name was carried forward, perhaps due to objections from geologists that this would create confusion with their pluton.

On June 11, 2008, the IAU Executive Committee announced a name, plutoid, and a definition: all trans-Neptunian dwarf planets are plutoids. The authority of that initial announcement has not been universally recognized:

...in part because of an email miscommunication, the WG-PSN [Working Group for Planetary System Nomenclature] was not involved in choosing the word plutoid. ... In fact, a vote taken by the WG-PSN subsequent to the Executive Committee meeting has rejected the use of that specific term..."

The category of 'plutoid' captured an earlier distinction between the 'terrestrial dwarf' Ceres and the 'ice dwarfs' of the outer Solar system, part of a conception of a threefold division of the Solar System into inner terrestrial planets, central gas giants and outer ice dwarfs, of which Pluto was the principal member. 'Ice dwarf' however also saw some use as an umbrella term for all trans-Neptunian minor planets, or for the ice asteroids of the outer Solar System; one attempted definition was that an ice dwarf "is larger than the nucleus of a normal comet and icier than a typical asteroid."

Since the Dawn mission, it has been recognized that Ceres is an icy body more similar to the icy moons of the outer planets and to TNOs such as Pluto than it is to the terrestrial planets, blurring the distinction, and Ceres has since been called an ice dwarf as well.

Criteria

The category dwarf planet arose from a conflict between dynamical and geophysical ideas of what a useful conception of a planet would be. In terms of the dynamics of the Solar System, the major distinction is between bodies that gravitationally dominate their neighbourhood (Mercury through Neptune) and those which do not (such as the asteroids and Kuiper belt objects). However, a celestial body may have a dynamic (planetary) geology at approximately the mass required for its mantle to become plastic under its own weight, which results in the body acquiring a round shape. Because this requires a much lower mass than gravitationally dominating the region of space near their orbit, there are a population of objects that are massive enough to have a world-like appearance and planetary geology, but not massive enough to clear their neighborhood. Examples are Ceres in the asteroid belt and Pluto in the Kuiper belt.

Dynamicists usually prefer using gravitational dominance as the threshold for planethood, because from their perspective smaller bodies are better grouped with their neighbours, e.g. Ceres as simply a large asteroid and Pluto as a large Kuiper belt object. However, geoscientists usually prefer roundness as the threshold, because from their perspective the internally driven geology of a body like Ceres makes it more similar to a classical planet like Mars, than to a small asteroid that lacks internally driven geology. This necessitated the creation of the category of dwarf planets to describe this intermediate class.

| Body | M/M🜨 (1) | Λ (2) | µ (3) | Π (4) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.055 | 1.95×103 | 9.1×104 | 1.3×102 | ||||||||

| Venus | 0.815 | 1.66×105 | 1.35×106 | 9.5×102 | ||||||||

| Earth | 1 | 1.53×105 | 1.7×106 | 8.1×102 | ||||||||

| Mars | 0.107 | 9.42×102 | 1.8×105 | 5.4×101 | ||||||||

| Ceres | 0.00016 | 8.32×10−4 | 0.33 | 4.0×10−2 | ||||||||

| Jupiter | 317.7 | 1.30×109 | 6.25×105 | 4.0×104 | ||||||||

| Saturn | 95.2 | 4.68×107 | 1.9×105 | 6.1×103 | ||||||||

| Uranus | 14.5 | 3.85×105 | 2.9×104 | 4.2×102 | ||||||||

| Neptune | 17.1 | 2.73×105 | 2.4×104 | 3.0×102 | ||||||||

| Pluto | 0.0022 | 2.95×10−3 | 0.077 | 2.8×10−2 | ||||||||

| Eris | 0.0028 | 2.13×10−3 | 0.10 | 2.0×10−2 | ||||||||

| Sedna | 0.0002 | 3.64×10−7 | <0.07 | 1.6×10−4 | ||||||||

|

Planetary discriminants of (white) the planets and (purple) the largest known dwarf planet in each orbital population (asteroid belt, Kuiper belt, scattered disk, sednoids). All other known objects in these populations have smaller discriminants than the one shown. | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Orbital dominance

Alan Stern and Harold F. Levison introduced a parameter Λ (lambda), expressing the likelihood of an encounter resulting in a given deflection of orbit. The value of this parameter in Stern's model is proportional to the square of the mass and inversely proportional to the period. This value can be used to estimate the capacity of a body to clear the neighbourhood of its orbit, where Λ > 1 will eventually clear it. A gap of five orders of magnitude in Λ was found between the smallest terrestrial planets and the largest asteroids and Kuiper belt objects.

Using this parameter, Steven Soter and other astronomers argued for a distinction between planets and dwarf planets based on the inability of the latter to "clear the neighbourhood around their orbits": planets are able to remove smaller bodies near their orbits by collision, capture, or gravitational disturbance (or establish orbital resonances that prevent collisions), whereas dwarf planets lack the mass to do so. Soter went on to propose a parameter he called the planetary discriminant, designated with the symbol µ (mu), that represents an experimental measure of the actual degree of cleanliness of the orbital zone (where µ is calculated by dividing the mass of the candidate body by the total mass of the other objects that share its orbital zone), where µ > 100 is deemed to be cleared.

Jean-Luc Margot refined Stern and Levison's concept to produce a similar parameter Π (Pi). It is based on theory, avoiding the empirical data used by Λ. Π > 1 indicates a planet, and there is again a gap of several orders of magnitude between planets and dwarf planets.

There are several other schemes that try to differentiate between planets and dwarf planets, but the 2006 definition uses this concept.

Hydrostatic equilibrium

Sufficient internal pressure, caused by the body's gravitation, will turn a body plastic, and sufficient plasticity will allow high elevations to sink and hollows to fill in, a process known as gravitational relaxation. Bodies smaller than a few kilometers are dominated by non-gravitational forces and tend to have an irregular shape and may be rubble piles. Larger objects, where gravitation is significant but not dominant, are "potato" shaped; the more massive the body is, the higher its internal pressure, the more solid it is and the more rounded its shape, until the pressure is sufficient to overcome its internal compressive strength and it achieves hydrostatic equilibrium. At this point, a body is as round as it is possible to be, given its rotation and tidal effects, and is an ellipsoid in shape. This is the defining limit of a dwarf planet.

| Comparative masses of dwarf planets | |

| Comparative masses of the likeliest dwarf planets, with Charon for comparison. Eris and Pluto dominate. Unmeasured Sedna is excluded, but is likely on the order of Ceres. |

| Comparison with Earth's moon | |

| The masses of the previous bodies compared to that of the Moon. The unit of mass is ×1021 kg. |

When an object is in hydrostatic equilibrium, a global layer of liquid covering its surface would form a liquid surface of the same shape as the body, apart from small-scale surface features such as craters and fissures. If the body does not rotate, it will be a sphere, but the faster it rotates, the more oblate or even scalene it becomes. If such a rotating body were to be heated until it melted, its overall shape would not change. The extreme example of a body that may be scalene due to rapid rotation is Haumea, which is twice as long along its major axis as it is at the poles. If the body has a massive nearby companion, then tidal forces cause its rotation to gradually slow until it is tidally locked, such that it always presents the same face to its companion. An extreme example of this is the Pluto–Charon system, where each body is tidally locked to the other. Tidally locked bodies are also scalene, though sometimes only slightly so. Earth's Moon is tidally locked, as are all the rounded satellites of the gas giants.

There are no specific size or mass limits of dwarf planets, as those are not defining features. There is no clear upper limit: an object in the far reaches of the Solar system that was larger or more massive than the planet Mercury might not have had the time needed to clear the neighbourhood of its orbit; such a body would fit the definition of a dwarf planet rather than a planet. The lower limit is determined by the requirements of achieving and retaining hydrostatic equilibrium, but the size or mass at which an object attains equilibrium and remains there depends on its composition and thermal history, not simply its mass. An IAU question-and-answer press release from 2006 estimated that objects with mass above 0.5×1021 kg and radius greater than 400 km (800 km across) would "normally" be in hydrostatic equilibrium ("the shape ... would normally be determined by self-gravity"), but that "all borderline cases would need to be determined by observation." This is close to what as of 2019 is believed to be the approximate limit for objects beyond Neptune that are fully compact, solid bodies, with Salacia (r = 423±11 km, m = (0.492±0.007)×1021 km) being a borderline case both for the 2006 Q&A expectations and in more recent evaluations, and with Orcus being just above the expected limit. No other body with a measured mass is close to the expected mass limit, though several without a measured mass approach the expected size limit.

Population of dwarf planets

There is no clear definition as to what constitutes a dwarf planet, and whether to classify an object as one is up to individual astronomers. Thus, the number of dwarf planets in the Solar System is unknown.

The three objects under consideration during the debates leading up to the 2006 IAU acceptance of the category of dwarf planet – Ceres, Pluto and Eris – are generally accepted as dwarf planets, including by those astronomers who continue to classify dwarf planets as planets. Only one of them – Pluto – has been observed in enough detail to verify that its current shape fits what would be expected from hydrostatic equilibrium. Ceres is close to equilibrium, but some gravitational anomalies remain unexplained. Eris is assumed to be a dwarf planet because it is more massive than Pluto.

In order of discovery, these three bodies are:

- Ceres

– discovered January 1, 1801 and announced January 24, 45 years before Neptune.

Considered a planet for half a century before reclassification as an

asteroid. Considered a dwarf planet by the IAU since the adoption of

Resolution 5A on August 24, 2006. Confirmation is pending.

– discovered January 1, 1801 and announced January 24, 45 years before Neptune.

Considered a planet for half a century before reclassification as an

asteroid. Considered a dwarf planet by the IAU since the adoption of

Resolution 5A on August 24, 2006. Confirmation is pending. - Pluto

– discovered February 18, 1930 and announced March 13. Considered a

planet for 76 years. Explicitly reclassified as a dwarf planet by the

IAU with Resolution 6A on August 24, 2006. Five known moons.

– discovered February 18, 1930 and announced March 13. Considered a

planet for 76 years. Explicitly reclassified as a dwarf planet by the

IAU with Resolution 6A on August 24, 2006. Five known moons. - Eris

(2003 UB313) – discovered January 5, 2005 and announced July 29. Called the "tenth planet"

in media reports. Considered a dwarf planet by the IAU since the

adoption of Resolution 5A on August 24, 2006, and named by the IAU

dwarf-planet naming committee on September 13 of that year. One known

moon.

(2003 UB313) – discovered January 5, 2005 and announced July 29. Called the "tenth planet"

in media reports. Considered a dwarf planet by the IAU since the

adoption of Resolution 5A on August 24, 2006, and named by the IAU

dwarf-planet naming committee on September 13 of that year. One known

moon.

The IAU only established guidelines for which committee would oversee the naming of likely dwarf planets: any unnamed trans-Neptunian object with an absolute magnitude brighter than +1 (and hence a minimum diameter of 838 km at the maximum geometric albedo of 1) was to be named by a joint committee consisting of the Minor Planet Center and the planetary working group of the IAU. At the time (and still as of 2021), the only bodies to meet this threshold were Haumea and Makemake. These bodies are generally assumed to be dwarf planets, although this has not yet been demonstrated:

- Haumea

(2003 EL61)

– discovered by Brown et al. December 28, 2004 and announced by Ortiz

et al. on July 27, 2005. Named by the IAU dwarf-planet naming committee

on September 17, 2008. Two known moons.

(2003 EL61)

– discovered by Brown et al. December 28, 2004 and announced by Ortiz

et al. on July 27, 2005. Named by the IAU dwarf-planet naming committee

on September 17, 2008. Two known moons. - Makemake

(2005 FY9)

– discovered March 31, 2005 and announced July 29. Named by the IAU

dwarf-planet naming committee on July 11, 2008. One known moon.

(2005 FY9)

– discovered March 31, 2005 and announced July 29. Named by the IAU

dwarf-planet naming committee on July 11, 2008. One known moon.

These five bodies – the three under consideration in 2006 (Pluto, Ceres and Eris) plus the two named in 2008 (Haumea and Makemake) – are commonly presented as the dwarf planets of the Solar System, though the limiting factor (albedo) is not what defines an object as a dwarf planet.

The astronomical community commonly refers to other larger TNOs as dwarf planets as well. At least four additional bodies meet the preliminary criteria of Brown, of Tancredi et al., and of Grundy et al. for identifying dwarf planets:

- Quaoar

(2002 LM60) – discovered June 5, 2002 and announced October 7 of that year. One known moon.

(2002 LM60) – discovered June 5, 2002 and announced October 7 of that year. One known moon. - Sedna

(2003 VB12) – discovered November 14, 2003 and announced March 15, 2004.

(2003 VB12) – discovered November 14, 2003 and announced March 15, 2004. - Orcus

(2004 DW) – discovered February 17, 2004 and announced two days later. One known moon.

(2004 DW) – discovered February 17, 2004 and announced two days later. One known moon. - Gonggong

(2007 OR10) – discovered July 17, 2007 and announced January 2009. Recognized as a dwarf planet by JPL and NASA in May 2016. One known moon.

(2007 OR10) – discovered July 17, 2007 and announced January 2009. Recognized as a dwarf planet by JPL and NASA in May 2016. One known moon.

For instance, JPL/NASA characterized Gonggong as a dwarf planet after observations in 2016, and Simon Porter of the Southwest Research Institute spoke of "the big eight [TNO] dwarf planets" in 2018, referring to Pluto, Eris, Haumea, Makemake, Gonggong, Quaoar, Sedna and Orcus.

Additional bodies have been proposed, such as Salacia and 2002 MS4 by Brown, Varuna and Ixion by Tancredi et al., and 2013 FY27 by Sheppard et al. Most of the larger bodies have moons, which enables a determination of their masses and thus their densities, which inform estimates as to whether they could be dwarf planets. The largest TNOs that are not known to have moons are Sedna, 2002 MS4, 2002 AW197 and Ixion.

At the time Makemake and Haumea were named, it was thought that trans-Neptunian objects (TNOs) with icy cores would require a diameter of only about 400 km (250 mi), or 3% the size of Earth—the size of the moons Mimas, the smallest moon that is round, and Proteus, the largest that is not—to relax into gravitational equilibrium. Researchers thought that the number of such bodies could prove to be around 200 in the Kuiper belt, with thousands more beyond. This was one of the reasons (keeping the roster of 'planets' to a reasonable number) that Pluto was reclassified in the first place. However, research since then has cast doubt on the idea that bodies that small could have achieved or maintained equilibrium under the typical conditions of the Kuiper belt and beyond.

Individual astronomers have recognized a number of objects as dwarf planets or as likely to prove to be dwarf planets. In 2008, Tancredi et al. advised the IAU to officially accept Orcus, Sedna and Quaoar as dwarf planets (Gonggong was not yet known), though the IAU did not address the issue then and has not since. In addition, Tancredi considered the five TNOs Varuna, Ixion, 2003 AZ84, 2004 GV9, and 2002 AW197 to most likely be dwarf planets as well. Since 2011, Brown has maintained a list of hundreds of candidate objects, ranging from "nearly certain" to "possible" dwarf planets, based solely on estimated size. As of 13 September 2019, Brown's list identifies ten trans-Neptunian objects with diameters then thought to be greater than 900 km (the four named by the IAU plus Gonggong, Quaoar, Sedna, Orcus, 2002 MS4 and Salacia) as "near certain" to be dwarf planets, and another 16, with diameters greater than 600 km, as "highly likely". Notably, Gonggong may have a larger diameter (1230±50 km) than Pluto's round moon Charon (1212 km).

However, in 2019 Grundy et al. proposed that dark, low-density bodies smaller than about 900–1000 km in diameter, such as Salacia and Varda, never fully collapsed into solid planetary bodies and retain internal porosity from their formation (in which case they could not be dwarf-planets), while accepting that brighter (albedo > ≈0.2) or denser (> ≈1.4 g/cc) Orcus and Quaoar probably were fully solid:

Orcus and Charon probably melted and differentiated, considering their higher densities and spectra indicating surfaces made of relatively clean H2O ice. But the lower albedos and densities of Gǃkúnǁʼhòmdímà, 55637, Varda, and Salacia suggest that they never did differentiate, or if they did, it was only in their deep interiors, not a complete melting and overturning that involved the surface. Their surfaces could remain quite cold and uncompressed even as the interior becomes warm and collapses. The liberation of volatiles could further help transport heat out of their interiors, limiting the extent of their internal collapse. An object with a cold, relatively pristine surface and a partially-collapsed interior should exhibit very distinctive surface geology, with abundant thrust faults indicative of the reduction in total surface area as the interior compresses and shrinks.

(Salacia was later determined to have a somewhat higher density, comparable within uncertainties to that of Orcus, though still with a very dark surface. Despite this determination, Grundy et al. characterized it as "dwarf-planet sized", while calling Orcus a dwarf planet. Later studies on Varda suggest that its density may also be high.)

Most likely dwarf planets

The trans-Neptunian objects in the following tables are agreed by Brown, Tancredi et al. and Grundy et al. to be probable dwarf planets, or close to it. Charon, a moon of Pluto that was proposed as a dwarf planet by the IAU in 2006, is included for comparison. Those objects that have absolute magnitudes greater than +1, and so meet the threshold of the joint planet–minor planet naming committee of the IAU, are highlighted, as is Ceres, which the IAU has assumed is a dwarf planet since they first debated the concept.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Exploration

On March 6, 2015, the Dawn spacecraft entered orbit around Ceres, becoming the first spacecraft to visit a dwarf planet. On July 14, 2015, the New Horizons space probe flew by Pluto and its five moons.

Ceres displays such evidence of an active geology as salt deposits and cryovolcanos, while Pluto has water-ice mountains drifting in nitrogen-ice glaciers, as well as a significant atmosphere. Ceres evidently has brine percolating through its subsurface, while there is evidence that Pluto has an actual subsurface ocean.

Dawn had previously orbited the asteroid Vesta. Saturn's moon Phoebe has been imaged by Cassini and before that by Voyager 2, which also encountered Neptune's moon Triton. All three bodies show evidence of once being dwarf planets, and their exploration helps clarify the evolution of dwarf planets.

Similar objects

A number of bodies physically resemble dwarf planets. These include former dwarf planets, which may still have an equilibrium shape or evidence of an active geology; planetary-mass moons, which meet the physical but not the orbital definition for dwarf planets; and Charon in the Pluto–Charon system, which is arguably a binary dwarf planet. The categories may overlap: Triton, for example, is both a former dwarf planet and a planetary-mass moon.

Former dwarf planets

Vesta, the next-most-massive body in the asteroid belt after Ceres, was once in hydrostatic equilibrium and is roughly spherical, deviating mainly because of massive impacts that formed the Rheasilvia and Veneneia craters after it solidified. Its dimensions are not consistent with it currently being in hydrostatic equilibrium. Triton is more massive than Eris or Pluto, has an equilibrium shape, and is thought to be a captured dwarf planet (likely a member of a binary system), but no longer directly orbits the sun. Phoebe is a captured centaur that, like Vesta, is no longer in hydrostatic equilibrium, but is thought to have been so early in its history due to radiogenic heating.

Evidence from 2019 suggests that Theia, the former planet that collided with Earth in the giant-impact hypothesis, may have originated in the outer Solar System rather than in the inner Solar System and that Earth's water originated on Theia, thus implying that Theia may have been a former dwarf planet from the Kuiper Belt.

Planetary-mass moons

At least nineteen moons have an equilibrium shape from having relaxed under their own gravity at some point in their history, though some have since frozen solid and are no longer in equilibrium. Seven are more massive than either Eris or Pluto. These moons are not physically distinct from the dwarf planets, but do not fit the IAU definition because they do not directly orbit the Sun. (Indeed, Neptune's moon Triton is a captured dwarf planet, and Ceres formed in the same region of the Solar System as the moons of Jupiter and Saturn.) Alan Stern calls planetary-mass moons "satellite planets", one of three categories of planet, together with dwarf planets and classical planets. The term planemo ("planetary-mass object") also covers all three populations.