Hyperspace (also, nulspace, subspace, overspace, jumpspace and similar) is a concept from science fiction relating to higher dimensions and a faster-than-light (FTL) method of interstellar travel that also occasionally appears in scientific works in related contexts. It is considered one of the more common science fiction tropes.

Its use in science fiction originated in the magazine Amazing Stories Quarterly in 1931. In most works, hyperspace is described as a dimension that can be entered and exited using rubber science, most often through a gadget known as a "hyperdrive". Many works rely on hyperspace as a convenient background tool enabling FTL travel necessary for the plot, with a small minority making it a central element of their storytelling.

Early depictions

Emerging in the early 20th century, within several decades hyperspace became a common element of interstellar space travel stories in science fiction. Many stories in the science fiction magazines which became popular around that time, particularly in the United States, introduced readers to hyperspace, an idea that the three-dimensional space can be "folded", so that two separate points may come into contact, usually through the use of some device, most often called a "hyperdrive". Another common explanation involves the concept of a parallel universe, much smaller than ours, which partially or fully can be "mapped" into ours, through which the objects travel through much faster than they could in our universe. One of the main reasons for the adoption of hyperspace concept are of the limitations of faster-than-light travel in ordinary space, which the hyperspace trope allowed writers to bypass.

Kirk Meadowcroft's "The Invisible Bubble" (1928) and John Campbell's Islands of Space (1931) feature the earliest known references to hyperspace, with Campbell, whose story was published in the magazine Amazing Stories Quarterly, likely being the first writer to use this term in the context of space travel. According to the Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction, the earliest known use of the word "hyper-drive" comes from a preview of Murray Leinster's story in Thrilling Wonder Stories 1944: "Once again Kim takes off in the Starshine with its hyper-drive to do battle in defense of the Second Galaxy." As related vocabulary evolved, entering or navigating the hyperspace often became known as "jumping", as in "the ship will now jump to hyperspace".

Other notable early works employing this concept include Nelson Bond's The Scientific Pioneer Returns (1940), where his vision of the hyperspace concept is described in detail. Isaac Asimov's Foundation series, first published between 1942 and 1944 in Astounding, featured a Galactic Empire traversed through hyperspace through the use of a "hyperatomic drive". In Foundation (1951), hyperspace is described as an "...unimaginable region that was neither space nor time, matter nor energy, something nor nothing, one could traverse the length of the Galaxy in the interval between two neighboring instants of time."According to The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Robert A Heinlein gave a particularly clear description of it in Starman Jones (1953). E. C. Tubb has been credited with playing an important role in the development of hyperspace lore; writing a number of space operas in the early 1950s in which space travel occurs through that medium. He was also one of the first writers to treat hyperspace as a central part of the plot rather than a convenient background gadget that just enables the faster-than-light space travel.

Later depictions

Over the coming decades, a number of related terms (such as imaginary space, interspace, intersplit, jumpspace, megaflow, N-Space, nulspace, slipstream, overspace, Q-space, subspace, and tau-space) were used by various writers, although none gained recognition to rival that of hyperspace. Out of various fictitious drives, by the mid-70s the concept of travelling through hyperspace by using a hyperdrive has been described as having achieved the most renown, and would subsequently be further popularized through its use in the Star Wars franchise. Philip Harbottle called the concept of hyperspace "one of the fixtures" of the science fiction genre as early as in 1963. Some works nonetheless use one or more of the hyperspace synonyms; for example, in the Star Trek franchise, the term hyperspace itself is only used briefly in a single episode ("Coming of Age") of Star Trek: The Next Generation, while a related set of terms - subspace, transwarp, mycelial network and most recently, proto-warp - are used much more often, while most of the travel takes place through the use of a warp drive.

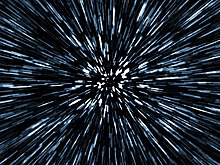

Stanley Kubrick's epic 1968 science fiction film 2001: A Space Odyssey features interstellar travel through a mysterious "star gate". This lengthy sequence, noted for its psychedelic special effects conceived by Douglas Trumbull, influenced a number of later cinematic depictions of superluminal and hyperspatial travel, such as Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979). In the 1974 film Dark Star, special effects designer Dan O'Bannon created a visual effect to depict the eponymous Dark Star spaceship accelerating into hyperspace by tracking the camera while leaving the shutter open. In this shot, the stars in space turn into streaks of light while the spaceship appears to be motionless. This is considered to be the first depiction in cinema history of a ship making the jump into hyperspace. The streaking hyperspace effect was later employed in Star Wars (1977) and the "star streaks" are considered one of the visual "staples" of the Star Wars franchise.

In some works, travelling or navigating hyperspace requires not only specialized equipment, but physical or psychological modifications of passengers or at least navigators, as seen in Frank Herbert's Dune (1965), Michael Moorcock's The Sundered Worlds (1966), Vonda McIntyre's Aztecs (1977), or David Brin's The Warm Space (1985).

Characteristics and uses

Hyperspace is generally seen as a fictional concept, incompatible with our present-day understanding of the universe (in particular, the theory of relativity). Occasionally the term – which originated in 19th-century mathematical texts – is used in academic works in the context of higher-dimensional geometry, popularized among others by theoretical physicist Michio Kaku's popular science book (Hyperspace, 1994). In mathematics, it is related to the concept of four-dimensional space, first described in the 19th century. Some science fiction writers attempted quasi-scientific rubber science explanations of this concept. For others, however, it is just a convenient MacGuffin enabling faster-than-light travel necessary for their story.

Hyperspace is generally described as chaotic and confusing to human senses; in some cases even hypnotic or dangerous to one's sanity, or at least unpleasant – transitions to or from hyperspace can cause symptoms such as nausea, for example. Visually, hyperspace is often left to the readers imagination, or depicted as "a swirling gray mist". In some works, it is dark. Exceptions do exist, for example, John Russel Fearn's Waters of Eternity (1953) features hyperspace that allows observation of regular space from within.

While mainly designed as a space-travel enabling trope, occasionally, some writers used the hyperspace concept in a more imaginative ways, or as a central element of the story. In Arthur C. Clarke's "Technical Error" (1950), a man is laterally reversed by a brief accidental encounter with "hyperspace". In George R.R. Martin's FTA (1974) hyperspace travel takes longer than in regular space, and in John E. Stith's Redshift Rendezvous (1990), the twist is that the relativistic effects within it appear at lower velocities. Hyperspace is generally unpopulated, save for the space-faring travellers. Early exceptions include Tubb's Dynasty of Doom (1953), Fearn's Waters of Eternity (1953) and Christopher Grimm's Someone to Watch Over Me (1959), which feature denizens of hyperspace. In The Mystery of Element 117 (1949) by Milton Smith, a window is opened into a new "hyperplane of hyperspace" containing those who have already died on Earth, and similarly, in Bob Shaw's The Palace of Eternity (1969), the hyperspace is a form of afterlife, where human minds and memories reside after death. In some works, hyperspace is a source of extremely dangerous energy, threatening to destroy the entire world if mishandled (ex. Eando Binder's The Time Contractor, 1937).

Many stories feature hyperspace as a dangerous place. Hyperspace is often described as being an unnavigable dimension where straying from a preset course can be disastrous. In Frederick Pohl's The Mapmakers (1955), navigational errors and the perils of hyperspace are one of the main plot-driving elements. In K. Houston Brunner's Firey Pillar (1955), a ship re-emerges within Earth, causing a catastrophic explosion.

In many stories, for various reasons, a starship cannot enter or leave hyperspace too close to a large concentration of mass, such as a planet or star; this means that hyperspace can only be used after a starship gets to the outside edge of a solar system, so the starship must use other means of propulsion to get to and from planets. Other writers have limited access to hyperspace by requiring a very large expenditure of energy in order to open a link (sometimes called a jump point) between hyperspace and regular space; this effectively limits access to hyperspace to very large starships, or to large stationary jump gates that can open jump points for smaller vessels. An example of this is the "jump" technology as seen in Babylon 5. Another would be the star gate seen in Arthur C. Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The reasons given for such restrictions are usually technobabble, but their existence is just a plot device allowing for interstellar policies to actually form and exist. Science fiction author Larry Niven published his opinions to that effect in N-Space. According to him, such an unrestricted technology would give no limits to what heroes and villains could do. Limiting the places a ship can appear in means that they will meet each other most often around contested planets or space stations, allowing for narratively satisfying battles or other encounters. On the other hand, less restricted hyperdrive may also allow for dramatic escapes as the pilot "jumps" to hyperspace in the midst of battle to avoid destruction.

James P. Hogan observed that (as of 1999) hyperspace still remains underutilized in science-fiction writing, treated too often as a plot-enabling gadget rather than as a fascinating, world-changing item, noting that for example there are next to no works that discuss the topic of how hyperspace has been discovered and how such discovery subsequently changed the world.

While generally associated with science fiction, hyperspace-like concepts exist in some works of fantasy, particularly ones which involve travel between different worlds or dimensions. In such works, such travel, usually done through portals rather than vehicles, is usually explained through the existence of magic.