How California’s Climate Policies Undermine Civil Rights and Racial Equity

At the age of 17, I won our nation’s closest equivalent to a national lottery, with full scholarships to Harvard, and then Stanford Law. The daughter and granddaughter of steelworkers, I grew up in Pittsburg, California, a gritty industrial town on the outskirts of the San Francisco Bay Area, with a significant Latino and Black workforce.

My dad’s dad and three uncles were recruited by US Steel from the fields near Fresno, where they worked alongside other Mexican immigrants picking produce. All the dads I knew worked at one of the town’s factories, mostly in union jobs for the biggest manufacturers: US Steel, Johns Manville, and Union Carbide. We were an AFL-CIO family.

My dad’s job at US Steel allowed us to live in the “middle” class: he had a secure job with medical and pension benefits and paid vacations. My siblings and I attended parochial school (tuition for all three of us was $21.00 per month). I learned to sail in a city recreation class, cutting through the rainbow surface sheen created by wastewater from the industrial plants that lined the Sacramento River.

Winters brought an annual day trip to the Sierras, where we slid down snowy hills on inner tubes and big plastic saucers. Summers brought beach trips to Santa Cruz, where the salt air provided welcome relief from the coughing and itching that assaulted us as soon as we popped back over the hill to the acute summer smog in the Bay Area.

That California no longer exists.

Soon after I started work in 1984 as a newly minted environmental lawyer in San Francisco, my dad and the vast majority of his fellow workers were permanently laid off from US Steel. He was 56.

While I spent my days puzzling through how to apply the exponentially expanding federal and state environmental laws, regulations, and judicial opinions to California’s factories, my parents catapulted into economic insecurity just as my sister started college and my brother completed his welding apprenticeship.

Fortunately, my parents owned their home. But my father’s pension and retirement benefits had been pared to pennies by the company’s bankruptcy. He would spend the rest of his working career earning near-minimum wages as a hardware store clerk. My parents’ home, like homes owned by both sets of grandparents, created the wealth that sustained my parents and long-widowed grandmothers through illness, job losses, and aging. Owning a home isn’t just a place to live: it’s the American Dream, our nation’s most successful pathway for elevating working families to the middle class.

My dad’s US Steel factory, like so many others in California’s rust belt, fell to global competition. But that isn’t the entire story. During this period, California’s environmental regulators were also piling on demands that made California’s factories even less able to compete. A General Motors plant in Los Angeles, for example, made Firebirds — GM’s signature muscle car. Red paint, as it turned out, required more solvents to achieve the essential shiny finish. In the 1980s, air regulators effectively gave GM the choice of staying in business without red Firebirds or shutting down. GM shut down, and thousands of workers lost good jobs.

That was only the beginning. As California’s industries shuttered, I lawyered the cleanup and redevelopment of these lands — turning factories into upscale mixed residential-retail projects, landfills into parks, tilt-up warehouses into expensive apartments for tech workers, and decayed single-occupancy hotels into gleaming high-rise towers.

I watched my big law firm peers, like the rest of California’s economic and political elites, retreat ever deeper into tiny White enclaves like Marin County, where they charge their electric vehicles with rooftop solar panels, send their kids off to elite schools with overpriced burlap lunch sacks, and clutch their stainless steel, reusable water bottles — all marketed as “green” products but mostly made in China by workers earning poverty wages, in state factories spewing pollution and powered by coal-dependent electric grids, and then shipped across the ocean in tankers powered by bunker fuel.

As the White environmentally minded progressives with whom I lived and worked allied with the state’s growing non-White population, California turned reliably blue, giving the Democratic Party an unbeatable electoral majority that was ostensibly a testament to the power of the state’s new majority of minorities. But the state’s White environmental donor class continued to wield outsized power within the progressive coalition.

In my 23 years as a token minority on the board of the California League of Conservation Voters, with White environmental donors and activists who cycled in and out of agencies like the California Air Resources Board (CARB) and Cal/EPA, a smattering of shorter-time tokens and I were lonely voices calling attention to how California’s supposedly world-leading environmental and climate regime was destroying the possibility of homeownership and manufacturing sector jobs for hardworking members of Latino, Black, and other minority communities.

During those years, I witnessed the creation and repeated emasculation of “environmental justice” groups. Often incubated, and always bullied and underfunded by White environmental advocacy groups and philanthropists, environmental justice advocates too often went along with fundamentally anti-growth policies that blocked housing that was still affordable to median-income households, shuttered unionized industries meeting the most stringent environmental, workplace safety, and labor protection standards in the nation, and prevented the expansion of the transportation, water, and public service infrastructure needed by California’s growing population.

Almost four decades after my dad lost his job, California’s air and water are cleaner. The state leads the world in renewable energy and electric vehicle ownership. But its industrial and manufacturing sectors have been decimated, and it boasts the highest housing, transportation, and electricity costs in the country. Its climate accomplishments are illusory, a product of deindustrialization, high energy costs, and, more recently and improbably, depopulation. Inequality has hit record levels, and housing segregation has returned to a degree not seen since the early 1960s.

California’s White progressive leadership boasts of creating a “just transition” to an equitable low-carbon future. But what I have witnessed over my now 37 years as an environmental and land-use lawyer has been something much darker: the creation of a new Green Jim Crow era in California.

1.

In 2019, nearly 60 percent of households earning over $150,000 per year were White; only 18 percent were Latino or Black. About 44 percent of all Black and Latino households earned less than $35,000 per year, near or below poverty levels in high-cost California. According to the United Ways of California, over 30 percent of California residents lack sufficient income to meet basic costs of living even after accounting for public assistance programs — those struggling families include half of Latino and 40 percent of Black residents.

Wealth disparities by race are even larger than income disparities, as are the barriers to homeownership.The US Census Bureau found that homeowners have 88.6 times the median net wealth of renting households, a median net wealth of $269,100 compared with just $3,036 for renters.

According to the state Legislative Analyst’s Office, just 30 zip codes housing just 2 percent of the population account for 20 percent of state wealth. Three-quarters of Californians live in the least wealthy 1,350 zip codes and hold less than one-third of the state’s wealth.

In 2019, 63 percent of all White California households were homeowners, but just 44 percent of California Latino and 36 percent of Black households owned homes. Federal Reserve data indicate that the wealth of Asian households that are not heavily represented in the state keyboard economy’s high-tech bracero program — the use of short-term HB-1 visas to import highly trained workers at bargain prices — lags far below the White population and aligns more closely with Black and Latino wealth.

For about 54 percent of all renters in California, housing costs exceed 30 percent of household income, the traditional definition of housing affordability. Nearly 70 percent of all state households with unaffordable housing costs consist of people of color.

Racial inequality is exponentially magnified by housing. Housing equity makes up nearly 60 percent of the total net worth of minority homeowners compared with 43 percent of White homeowner wealth. Black, Latino, and other historically disadvantaged groups rely on mortgage payments to build wealth through homeownership while also paying for necessary housing; there is little to no excess cash available to buy stocks, bonds, and other assets.

In January 2021, the median California home cost nearly $700,000, up 21 percent from the prior year, and required an annual income of $122,800 to qualify for a mortgage of $3,070 per month. Based on that measure, only 20 percent of state Latino and Black households, half the national rate, could qualify to buy a house in the state compared with 40 percent of White households.

In jobs-rich western Bay Area counties, median homes cost $1.3 million to $1.65 million. In this, the heart of progressive California, homes are unaffordable for 92 percent of Black, 85 percent of Latino, and 78 percent of Asian households compared with 35 percent of White households. As president of the California Association of Realtors noted, “The wide affordability gap in California between Whites and people of color demonstrates the legacy of systemic racism in housing, which has created inequities in homeownership rates across these communities.”

For this reason, the civil rights movement has for years prioritized expanding minority homeownership rates to close racial wealth gaps caused by housing discrimination. The state’s climate policies now directly impede this critical homeownership goal by demanding that the vast majority of new housing be built in the state’s most expensive urban infill locations as high-density, multifamily, and almost invariably rental projects.

Housing in these locations and this physical form is the most costly of all to construct — far more costly than wood-framed single-family homes, duplexes, townhomes, and garden apartments. Simple economics explains why most people do not live in high-rise buildings in high-rise neighborhoods in California cities.

Worse, this climate-based housing policy accelerates the displacement of communities of color from urban employment centers and, in many high-profile examples, gentrifies these neighborhoods for affluent professionals. San Francisco, Oakland, and Los Angeles, all epicenters of California’s progressive elites, boast shiny new residential towers alongside soaring homelessness rates and declining minority populations.

Because high-density urban housing units are so expensive to build, rents for even the smallest new studio apartment are often more than median monthly mortgage costs. The few households of color that can pay such exorbitant rents build no equity over time. Most are displaced to increasingly concentrated pockets of poverty in urban locations or to outer suburbs from which they must commute for hours each day.

The second supervisorial district in Los Angeles County has been called “the crowning glory of black political power in Southern California.” Bowing to the infill demands of White climate advocates, Herb Wesson, the Black former president of the Los Angeles City Council, expedited approvals for a 1,200-unit housing project next to a light rail stop. It features a radiant blue 30-story luxury high-rise called the “Arq” — the only such structure for miles. The Arq is surrounded by dense rectangles of lower-rise apartment blocks that physically fortify the tower from neighboring communities of color. The entire project offers no affordable housing. Prior to the pandemic, studio apartments rented for $3,121 per month, and two-bedroom units were $5,292 per month.

The executive director of the Crenshaw Subway Coalition, a community group working for equitable housing and development in the area, characterized the project as a “poster child for wildly out-of-scale development,” arguing that it is “clearly not for existing residents,” “feeds concerns about gentrification,” and was aimed at “upscale employees in nearby Culver City, while acting as a slap in the face to the surrounding South Los Angeles neighborhoods of mostly Black and Latino residents.”[17]The city council approved the project without a single local hire requirement. In November 2020, Wesson lost by a landslide in his bid to win a seat on the Los Angeles Board of Supervisors in an election marked by opposition to gentrification.

Similar examples abound statewide and have spilled over into the homeless crisis. In an order demanding that Los Angeles house tens of thousands of “skid row” unhoused residents, Federal District Judge David Carter noted:

"Nearly half of newly constructed [housing] units in Los Angeles between 2012 to 2019 were in lower-income communities. Yet 90% of the new construction during that period is unaffordable to working-class tenants in Los Angeles. By concentrating new housing initiatives in lower income-communities [which are also more likely to have frequent transit service], older buildings are razed and replaced by higher cost units, further decreasing the availability of affordable living for tenants in those communities and driving gentrification."

Demands from California’s climate and environmental advocates for high-density urban housing are making it less possible for Black, Latino, and other residents of color to even stay in their own neighborhoods, let alone buy a home.

2.

California’s racist climate housing policies are strongly linked to its racist climate transportation policies. Limiting new housing to high-density residences in transit-dependent neighborhoods is intended to reduce greenhouse gases (GHG) by demanding that people drive less, take the bus or other public transit more, and reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT). CARB has decided that a 15 percent reduction in statewide VMT is required to achieve an unlegislated GHG reduction target by 2050. CARB has pursued this VMT mandate even though Governor Gavin Newsom, in September 2020, issued an executive order directing that all new passenger cars and trucks be zero-emission by 2035.

CARB’s fealty to mass transit compounds the economic unattainability of housing. Researchers have repeatedly documented that the lack of affordable automobile ownership is a key driver of racial inequality, reducing employment, weekly hours worked, and hourly earnings for low-income workers.[20]Public transit, the “solution” wealthy Whites imagine will supplant personal vehicles, does not work for many people in less-affluent communities of color, where housing, employment, and other opportunities are often more dispersed and many more jobs can be accessed in a 30-minute drive than a 30-minute ride on public transit. Unlike affluent residents in the keyboard economy, workers of color more often have multiple jobs, commute during non-peak hours, and simply cannot use transit to “balance work, child care, elder care.”

The fact that “poor people tend to convert even small increases in income into vehicle purchases,” a recent UCLA study observed, is “testament to how valuable vehicle access” is for disadvantaged communities. It’s also why, despite billions spent on new rail and bus facilities, transit ridership throughout the state was rapidly falling even before the pandemic. Low-income, primarily Black and Latino workers make fewer but more essential automobile trips, with greater social benefits for work, food, health, and other necessities. Wealthier, largely White residents take far more discretionary personal automobile trips.

CARB’s VMT reduction mandate does not affect housing or transportation for largely White homeowners living in homes that already exist. Instead, CARB compounds racist housing and mobility constraints by requiring that aspiring homeowners who can afford to buy only less expensive and, for many, more desirable suburban-scale housing instead of living in smaller, higher density rental apartments in transit-dependent neighborhoods somehow reduce their per capita VMT by at least 15 percent in relation to a county-wide average VMT. Authorities in San Diego County determined that the state’s VMT reduction mandate, which has never been achieved in California or any other state, would increase the cost of each home between $50,000 and nearly $700,000.

Fresno, one of the state’s more affordable cities for aspiring homeowners, has a Black and Latino population of nearly 60 percent compared with a White population of 27 percent. In June 2020, Fresno’s elected leaders embraced the state’s VMT reduction requirement even though city council members admitted they had no idea how it could be achieved or would affect housing costs. City staff cited a building industry estimate that VMT constraints could add at least $23,000 to the cost of new residences in the city, but quickly acknowledged that “it could cost more.” Nevertheless, the council dutifully imposed the mandate by a vote of 5–1.

Neither San Diego County nor Fresno officials can promise that any fee will actually result in anyone driving any less. What is known is that even high-density, high-cost housing built on infill lots in suburban neighborhoods cannot change the transportation options available to residents in that location. Existing (Whiter, wealthier) homeowners again get a climate pass, while aspiring new homeowners get a massive VMT fee: housing injustice compounded by transportation injustice.

Even without the VMT mandate, climate leaders are demanding Californians spend far more on transportation. Governor Newsom signed his executive order banning the sale of internal combustion vehicles on the hood of an electric vehicle (EV) costing more than $50,000, while used compact cars affordable to low-income Californians cost $2,500. “How will my constituents afford an EV?” asked assembly member Jim Cooper on the day the order was signed. “They can’t. They currently drive 11-year-old vehicles.”

A 2015 analysis concluded that the cost of providing newer, cleaner, and much less expensive conventional vehicles to low-income workers in California was about $12,000 per car. This cost, the study concluded, “would probably limit the appeal” of such a program to just “a small number of households.” Much higher subsidies are necessary to provide lower-income residents with access to far more expensive EVs.

In 2021, the California legislature and governor again resisted efforts by environmental justice advocates to limit taxpayer subsidies for EV purchasers to middle- and lower-income workers. Instead, such subsidies will continue to be available to all EV purchasers — the vast majority of whom are White or Asian, male, earn over $100,000, live in the state’s wealthier coastal areas, and drive less than those in more distant affordable communities.

3.

CARB’s VMT mandate is already reshaping housing planning across the state in ways that replicate the state’s historically redlined and racist housing patterns.

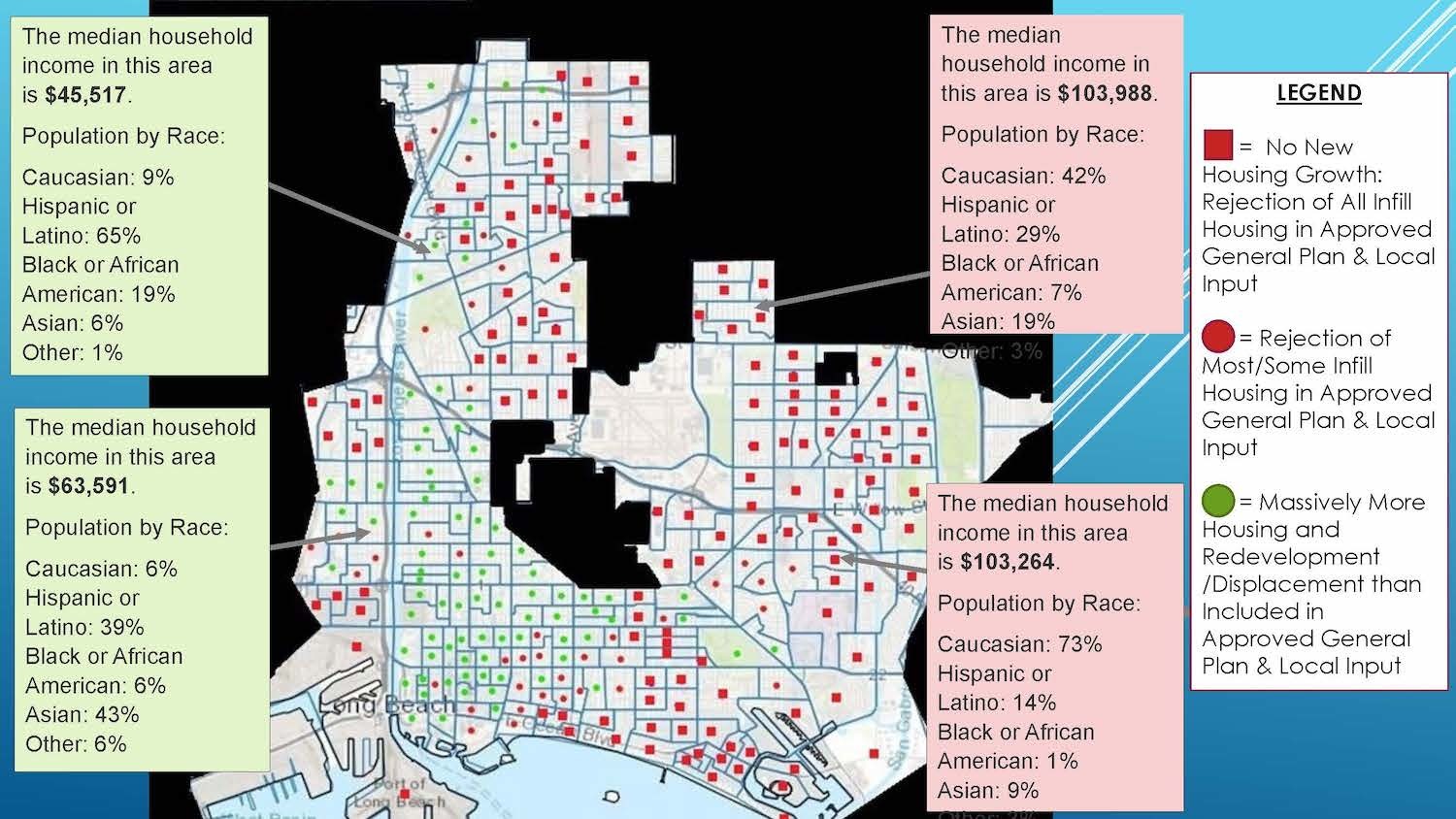

In 2020, the Southern California Association of Governments (SCAG), a regional agency charged with planning adequate and equitable transportation, housing, and economic development for most of Southern California, created maps for new housing at densities and locations needed to achieve a regional 19 percent VMT reduction target by 2035 mandated by CARB. The region has a projected 1.3 million-unit housing shortfall over the next decade. SCAG staff determined that new housing should be in neighborhoods where per capita VMT was already low due to either (i) housing overcrowding or (ii) proximity to frequent fixed-route public transit, which is legally presumed by state regulators to cause residents to drive fewer miles. The result, depicted in Figures 1, 2, and 3, perfectly aligns with the region’s historical pattern of racist redlining: no new housing should be built in majority-White wealthy neighborhoods, while massive blocks of multifamily housing should be crammed into low-income community of color neighborhoods.

Figure 1 shows the alignment of VMT with

historical redlining in Long Beach, as hauntingly described by Richard

Rothstein in his myth-busting book, The Color of Law, in which he proves that racial residential segregation was de jure — created by law and government policy, not by de facto capitalism or private “choice.”

To reduce VMT from new housing, no new housing should be built in the red square polygons, most of which consist of historically White-only, single-family home neighborhoods constructed by the aerospace industry for its White workforce. The median income of over $100,000 in these “high VMT” neighborhoods substantially exceeds the region’s average, and the majority or plurality of households are White.

In contrast, most new housing is to be built in the green polygons consisting of the poorest neighborhoods of Long Beach, with the highest percentage of community of color households and lowest percentage of White households, and which are bisected by a light rail line and thereby qualify for the state’s legal presumption of lower car use. SCAG’s staff and consultant team blithely defended this housing pattern until called to account — and were then forced to acknowledge the conflict between California’s housing laws and climate goals. SCAG’s governing body of elected officials subsequently prohibited use of the staff’s VMT redlining plan.

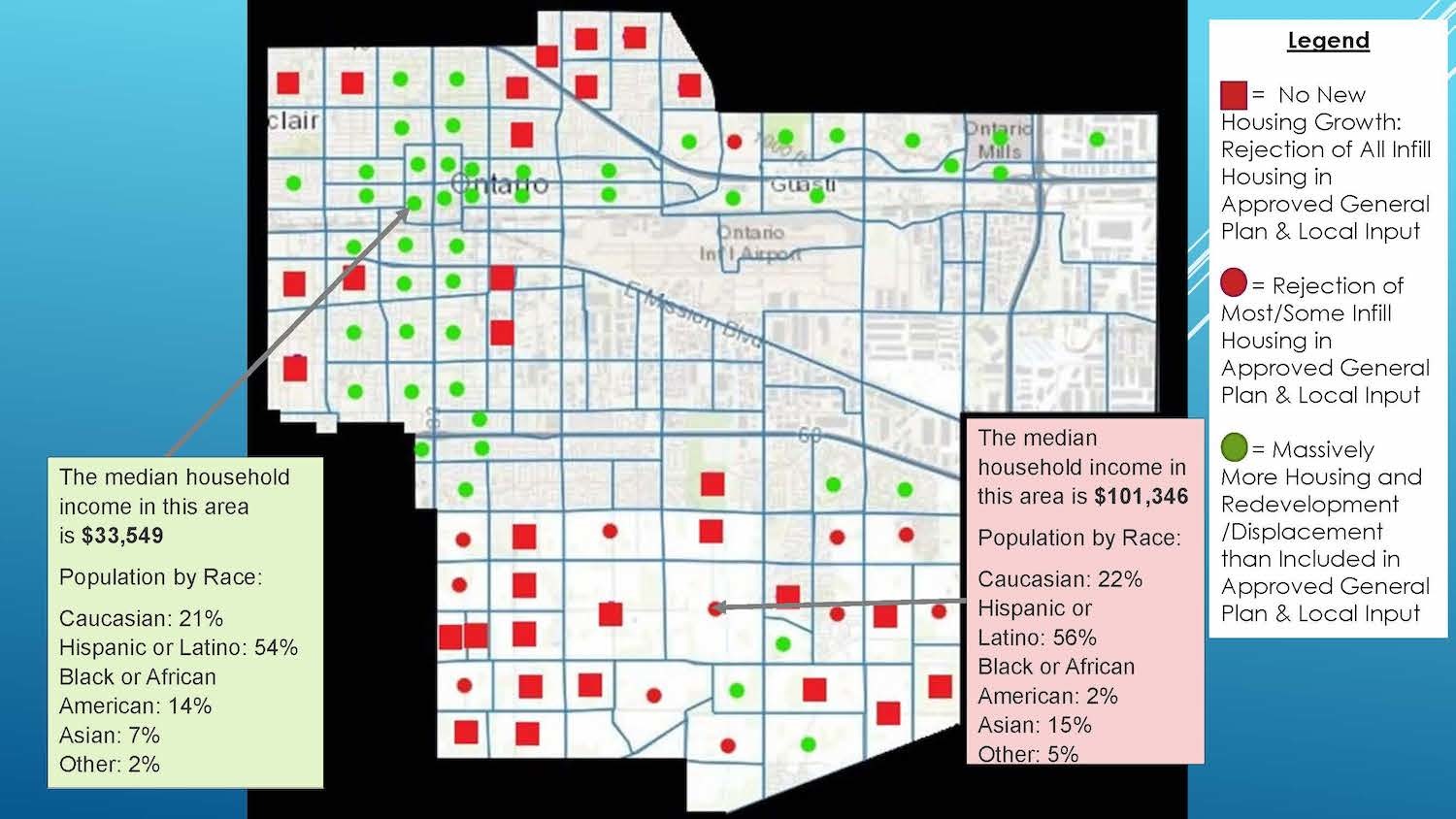

SCAG’s VMT-based housing plans repeated this pattern everywhere

in the region, doing exactly what Judge Carter found Los Angeles had

done by concentrating costly new housing in the region’s lowest-income

neighborhoods. The VMT regime’s fierce rejection of homeownership was

most vividly on display in Ontario, one of the largest cities in the

fast-growing “Inland Empire” east of the coastal counties. Ontario had

long planned the buildout of its southern neighborhoods to accommodate

new homes affordable for purchase by median-income families: typically

two-story houses on small lots with a mix of walkable schools, parks,

and retail destinations. SCAG’s plan was to end housing construction in

Ontario’s southern neighborhoods, even though these homes were already

under construction and selling briskly — mostly to Latinos and other

people of color.

In

Ontario, as in Long Beach, SCAG’s VMT plan called for new housing to be

built in poorer minority neighborhoods served by a bus or in the city’s

bustling commercial employment centers located next to a freeway used

by a bus. Displacement of poor minority residents and local jobs was not

a factor for the SCAG VMT climate “expert” consultant team.

The Bay Area is also remarkably segregated. In early 2021, climate-friendly San Francisco leaders were stunned when the Bay Area equivalent of SCAG proposed a “smart growth” plan that forced hundreds of thousands of high-cost, high-density housing into the region’s few remaining legacy minority communities. The plan largely ignored building housing in locations like infamously racist Marin County. “It’s Black and brown families that get displaced” by bunching dense new apartments near transit to cut greenhouse gas emissions, one San Francisco County supervisor told the San Francisco Chronicle. “We have seen this show before.”

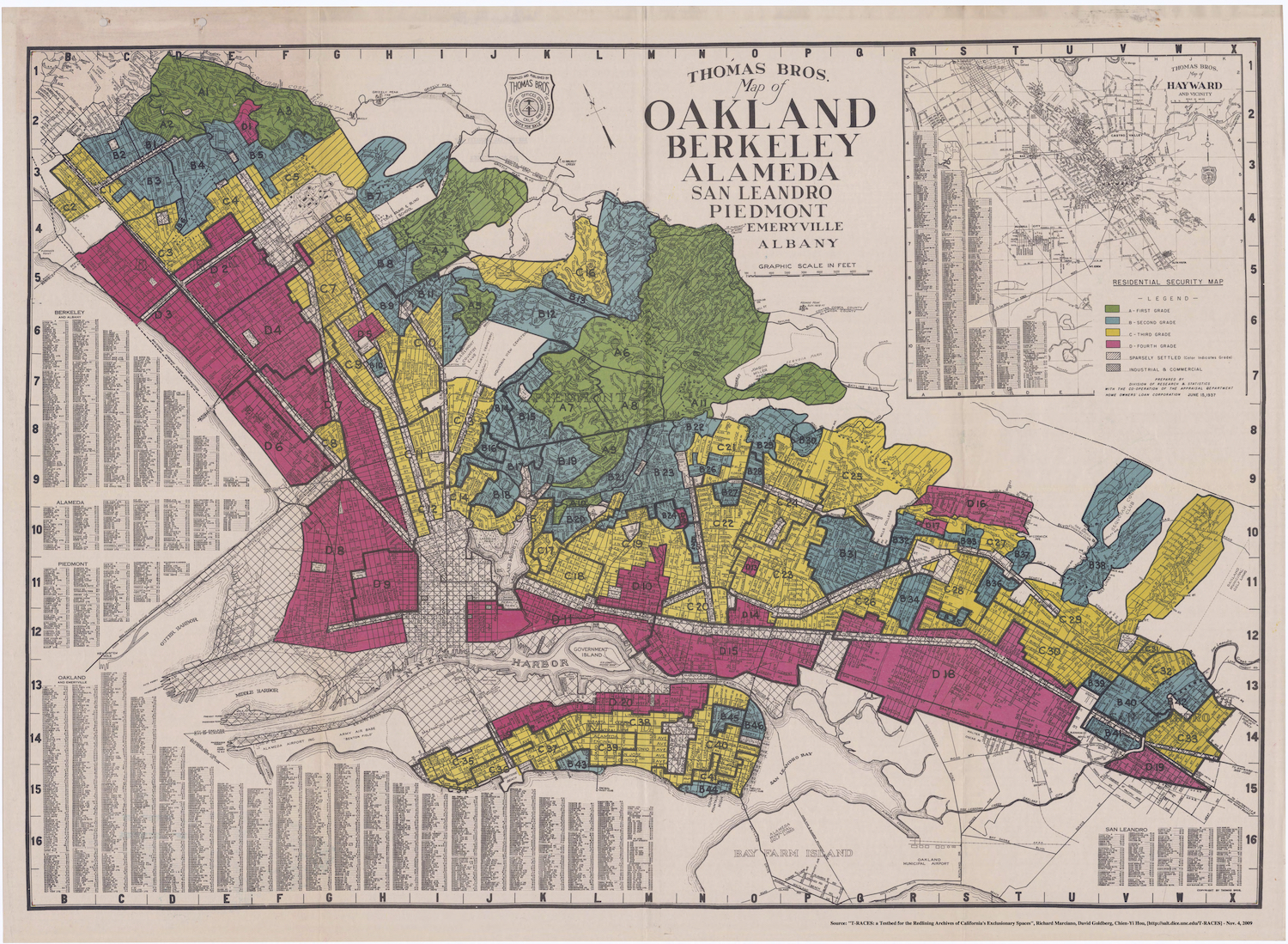

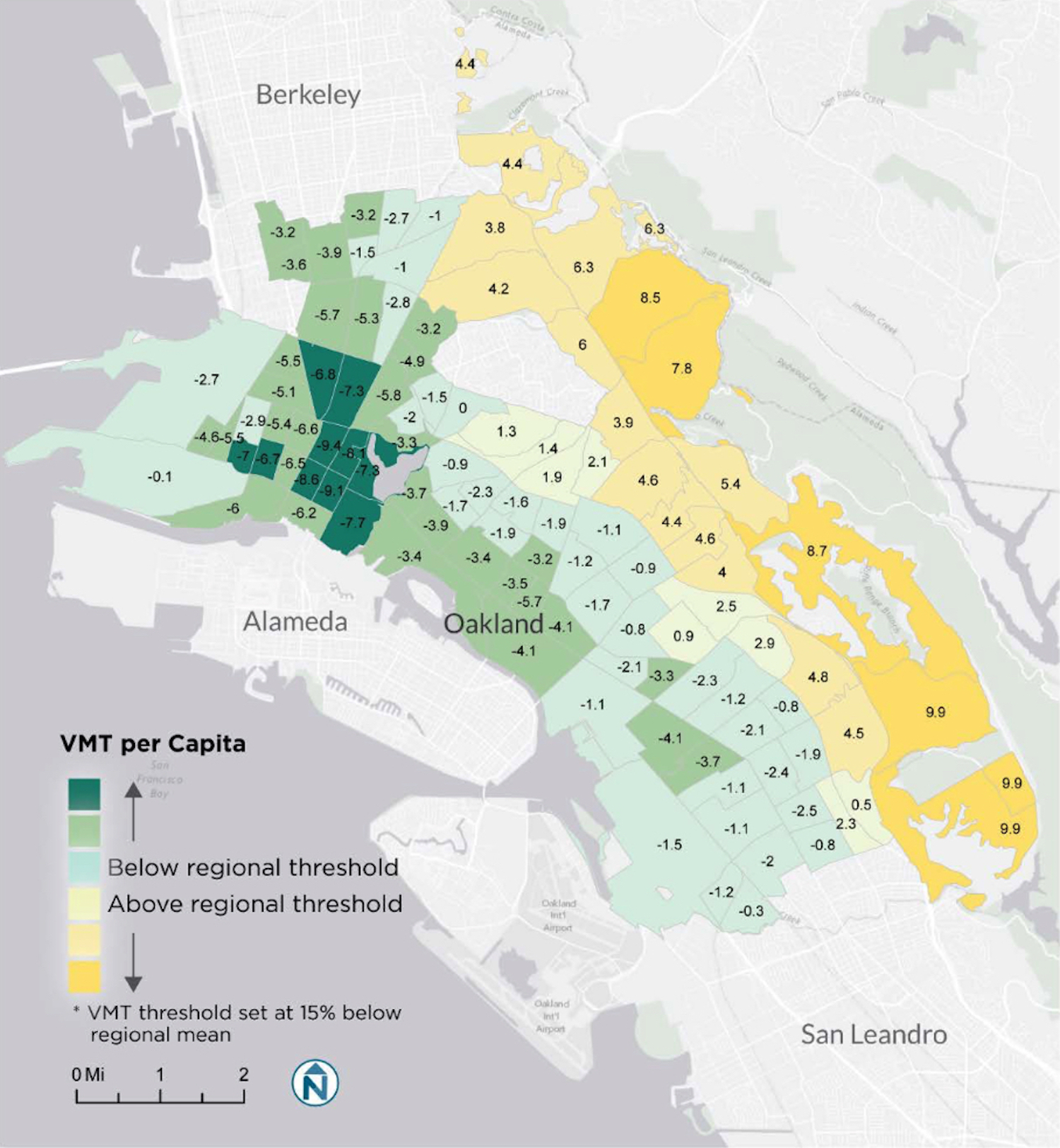

The low-VMT planning maps for the Bay Area also replicate the racially exclusionary and displacement/gentrification patterns proposed by SCAG staff in Southern California. Figure 3 shows the historical redlining map of Oakland, where communities of color were denied access to federally insured mortgages in the flatlands while White wealthy hill communities to the east of the city center had ready access to such mortgage assistance. The “low VMT” Oakland map where new housing is to be concentrated aligns nearly precisely with the redlined Black neighborhoods, whereas the “high VMT” wealthy White neighborhoods where housing is to be avoided in the name of climate change were the longtime beneficiaries of federally insured mortgages.

White, affluent climate activists insist they will help fund “affordable housing” for displaced households of color. But no existing or reasonably foreseeable funding could possibly redress the harm created by climate housing and VMT racism, nor is “affordable housing” a lawful substitute for attainable homeownership.

In the Bay Area alone, planners estimate that subsidies of $43,000 to $163,000 per unit, a total of $443 million to $2.3 billion, would be needed to make “climate-friendly” housing even remotely affordable for all but the most affluent. In 2016, the state Legislative Analyst’s Office estimated that subsidies of $165,000 per unit would be necessary for affordable housing in coastal communities. Statewide, the cost would be $250 billion.

These calculations also fail to account for the fact that simply making infill housing affordable to qualifying low-income households, via either subsidized rents or below market sale with deed restrictions that limit resale value, can’t build equity and wealth for these households in the way that traditional homeownership does. And all of these estimates predate the pandemic, which disproportionately and severely reduced the employment, income, and health of state communities of color and raised the required level of subsidies for high-cost housing.

Notwithstanding progressive rhetoric about diversity and inclusion, California’s climate policy makers are not planning for housing typologies or transportation solutions that actually pencil out for aspiring median-income homeowners, the majority of whom are no longer White.

4.

Adding insult to injury, California’s energy policies disproportionately hit low- and median-income communities of color coming and going, raising household energy costs while limiting opportunities for employment in the well-paying, often-unionized, energy-intensive sectors of the state’s economy.

Black and Latino households are already forced to pay from 20 to 43 percent more of their household incomes on energy than White households. A household energy cost of more than 6 percent of total income is considered the measure of energy poverty. In 2020, over 4 million households in California (30 percent of the total) experienced energy poverty. Over 2 million households were forced to pay 10 to 27 percent of their total income for home energy. Between 2011 and 2020, the state’s home energy affordability gap rose by 66 percent, while falling by 10 percent in the rest of the nation.

California has the highest electricity and highest gasoline costs in the nation, with electricity prices 50 percent higher than the national average and gasoline costs exceeding even import-reliant Hawaii in the center of the Pacific Ocean. “These higher costs,” assembly member Cooper wrote in a 2020 letter to environmental groups, “impact disadvantaged communities, especially those who live in areas like the Central Valley, and force them to pay more for energy costs than coastal community households do.”

The state’s generous net metering policies for rooftop solar panels are already making these inequities worse, as the costs of these programs are ultimately paid for predominantly by the state’s less-wealthy homeowners and renters. In 2021, legislation introduced by assembly member Lorena Gonzalez to end these racist solar subsidies was defeated, following pressure from the state’s environmental and climate advocacy groups.

But unaffordable utility bills are only half the story. California climate policies also require the elimination of hundreds of thousands of conventional energy jobs, and will adversely affect millions of other jobs in energy-dependent and related industries. These sectors provide stable, higher-paying employment for less educated residents, the majority of whom are workers of color and recent immigrants. In 2019, 29 percent of all new immigrants had not graduated from high school. A further 20 percent finished high school but did not attend college. As better-paying blue collar work has evaporated, most have ended up in the state’s lowest-paying jobs — that massive cohort of nearly 40 percent of Californians who cannot afford to pay routine monthly expenses.

An analysis of 2017 data by the Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation (LAEDC) found that “across all levels of education, earnings are higher in oil and gas industries compared to the all industry average.” The energy sector provides over 152,100 direct and 213,860 indirect and induced jobs in California that pay higher wages and benefits for individuals with lower levels of education. This workforce is ethnically and racially diverse, and about 63 percent of all employees have less than a bachelor’s degree.

LAEDC also showed that another 3.9 million California jobs (16.5 percent of total state employment) rely on purchases from or use products sold by state energy producers, including chemical, machinery, and metal products manufacturing, wholesale trade, utilities, and transportation, as well as professional, scientific, and technical services. Most of these sectors also provide higher-paying jobs for workers of color, often in more affordable areas of the state. These jobs are also at risk from the forced elimination of the in-state energy sector.

California climate advocates have utterly failed to provide a convincing explanation for how workers of color employed in existing energy and energy-dependent sectors will support their families once these industries are gone. Many, like the fantastically wealthy, famously haughty John Kerry, now the nation’s “climate envoy,” airily suggest that green employment will replace job losses in the fossil fuel sector. Even the staunchly progressive Washington Post conceded that this was unlikely, noting that rapid growth in the wind and solar industries over the next decade could plausibly replace at most 20 percent of the workforce of the coal industry alone.

Trade unions and their Democratic political allies aren’t buying what California’s climate cognoscenti are selling either. “Career opportunities for renewables are nowhere near what they are in gas and oil, and domestic energy workers highly value the safety, reliable duration and compensation of oil and gas construction jobs,” North America’s Building Trades Unions said in July 2020 after conducting two studies of the industry. “We can hate on oil, but the truth is our refinery jobs are really good middle class jobs,” echoed California state senator and labor leader Lorena Gonzalez. “Jobs can’t be an afterthought to any climate change legislation. We must have specific plans that accompany industry changes.”

There are no such plans. California’s oil consumption continues, slowing only with the pandemic, while progressive climate elites see no irony in forcing California’s minority communities out of jobs while importing more oil from Saudi Arabia and other countries not known for adherence to progressive labor, gender, environmental, or civil rights values.

Instead, many climate advocates have retreated to vague notions of supplying a forcibly unemployed workforce with a universal basic income or universal basic services. Even then, some would limit such subsidies to what they determine will meet only basic costs of living and “sharply reduce consumption of material goods created in environmentally harmful ways.” The Bay Area’s Metropolitan Transit Commission recently proposed a $205 billion statewide universal basic income program, comprising a $500 monthly payment to all households. Even were the state, or even the wealthy Bay Area, willing to enact such a program, it would offer pitifully little income support for low-income households. For comparison’s sake, federal unemployment insurance during the pandemic offered $400–600 per week to individuals.

One thing, though, seems much more certain. State climate leaders appear determined to continue to impose regressive and racist deindustrialization schemes on aspiring communities of color.

5.

All of these racist housing, transportation, and energy outcomes will occur even if everything goes as planned by state climate authorities. It almost certainly won’t.

In 2008, California voters approved an initiative for a high-speed rail line linking Los Angeles, Sacramento, and San Francisco at a cost of $33 billion. Thirteen years later, costs rose to more than $100 billion. By 2021, the state was struggling to complete just a 171-mile line from Merced to Bakersfield with a track right of way of about 1,000 acres.

California already imports more than 25 percent of current state electrical demand. To electrify buildings and light-duty vehicles by 2050, it must successfully build, connect, and deliver electricity from new solar and wind installations about 100 to 300 times the size of the still-uncompleted Merced to Bakersfield high-speed rail line each year for the next 30 years. The state has not identified or secured rights to use more than a minute fraction of the land this sprawling, multidecade energy development project will require.

Environmental challenges alone will almost certainly preclude anything like the mammoth scale of new energy construction imagined by California climate advocates. In 2019, the state’s own electrification consultants prepared a study for The Nature Conservancy showing that new solar and wind facilities consistent with the state’s clean energy targets threatened sensitive habitats and resources throughout the western United States. The study concluded that more environmentally protective development scenarios were significantly more costly without a large-scale expansion of interstate transmission capabilities.

Meanwhile, local governments (and voters) are increasingly resistant to utility-scale renewable development. San Bernardino County, the largest county in California, comprising much of the state’s prime wind and solar sites, has banned the construction of new industrial-scale wind and solar facilities on over a million acres of land.

Then there’s the need to locate, mine, and refine unparalleled amounts of raw materials to manufacture millions of solar panels, wind generators, grid-scale batteries, grid distribution and transmission upgrades, and millions of new electrical home heating, cooling, cooking, and water-heating appliances and EVs. No one knows whether the world’s mining and manufacturing capacity can feasibly meet California’s demand, let alone global demand. Some key materials, including graphite, lithium, and polysilicon used in renewable generation, are produced using child or forced labor in unsafe conditions.

California also has not yet comprehensively planned for renewable energy waste management, including the need to replace and dispose of a massive amount of worn-out panels, turbines, and batteries each year. Nor has the cost of actually electrifying and retrofitting existing buildings and installing enough chargers and other infrastructure for a statewide fleet of EVs been fully assessed. In the UK, cost estimates for decarbonizing just residential buildings by 2050 are now said to have been underestimated by up to $90 billion. A former principal policy advisor for the California Energy Commission estimates that the bill for state electrification is $2.8 trillion, which would be $71,400 per capita.

Even if solar, wind, and battery prices continue to fall as state bureaucrats hope, wind and solar power require backup supplies to maintain grid frequency and reliability. Climate regulators use terms like “net zero carbon” to mask reliance on natural gas generation, excuse the shutdown of the state’s sole nuclear plant, resist increasing pumped generation even from existing hydroelectric reservoirs, and block biomass generation — notwithstanding the state’s urgent need to reduce catastrophic wildfire risks by removing dead and dying vegetation caused by a century of forest mismanagement and periodic droughts.

Numerous studies from leading researchers have now demonstrated that running California’s entire electrical grid on wind, solar, and batteries alone, as much of the state’s environmental leadership insists, is both infeasible and almost unimaginably costly. For all of these reasons, it is highly unlikely that California will successfully electrify as planned by 2050.

Meanwhile, California’s affluent White homeowners have already seen the future of the California electricity grid — and it’s ugly. With planned blackouts to reduce wildfire risks, many of California’s most affluent communities experienced multiple days without electricity: no EV car charging, no smartphones or laptops, no refrigerated food, no electric cooktops or microwaves. Their response, predictably, was to rush to restore reliable on-demand electric supplies affordable only to homeowners with extra cash on hand, who bought either home-based generators (propane or gasoline) or their own solar battery storage array.

California’s future electricity system is on track for the wealthy to continue to have on-demand reliable electricity, either self-generated and stored or at ever-escalating costs. Everyone else will need to make do with unreliable and costly electricity.

6.

What the soaring environmental rhetoric of the state’s affluent, largely White technocratic leadership disguises is a kludge of climate policies that will only, under the best of circumstances, partially decarbonize the state’s economy while deepening the state’s shameful legacy of racial injustice.

Why, then, has the nation’s most diverse state, and by many accounts its most progressive, undertaken such a racist climate social engineering project? Part of the answer is that the climate agenda is almost entirely a creation of affluent White European and North American scientists and environmental advocates. The New York Times has characterized the geosciences as one of “the least diverse” of “all fields of science,” a problem that adversely affects research “quality and focus . . . especially on climate change.”

Scientists have long established a strong relationship between rising atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases and rising global temperatures. But efforts to project the likely increase in temperatures and the impacts associated with that warming into the future remain fraught with uncertainty.

Nonetheless, an affluent, insular, White research community has, for years, advanced a highly misleading representation of climate risk, publishing over 4,000 peer-reviewed articles that misconstrued highly improbable catastrophic climate scenarios as a terrifying vision of a “business as usual” future. These scenarios are then further amplified through the failure to take into account the capacity of societies to adapt to a warming climate. The worst-case scenarios that so much of the climate impact literature has been overly dependent upon are also those with the highest energy use and economic growth, both of which are highly correlated with greater climate resilience.

The state’s overwhelmingly White climate activists, underwritten by its overwhelmingly White billionaires, have, in turn, demanded unprecedented action to remake the state’s economy and its communities in response to an existential threat, one that they explicitly assert trumps all other concerns. They do so, outrageously, in the name of protecting so-called frontline communities — meaning low-income communities of color in the United States and around the world — even though the primary factor that makes those communities vulnerable is their poverty and even as those ostensibly advocating for actions to address the problem advocate for climate mandates that are demonstrably making those communities poorer and more vulnerable to climate change.

The state’s exclusively White, wealthy, climate-centric governors — and CARB’s immediate past chair, Mary Nichols, who served under each — have responded by designing California’s climate agenda, to a historically unmatched extent, through executive fiat in lieu of democratic legislation.

The state’s first sweeping climate change executive order was signed by Arnold Schwarzenegger, a multimillionaire actor. This was followed by orders penned by Jerry Brown, heir to a California political dynasty, who is now comfortably retired on his 2,514-acre ranch. Today’s marching orders, such as the phaseout of internal combustion engines in new vehicles, emanate from Gavin Newsom, a privileged son of Marin County, who has been lavishly supported throughout his business and political career by some of the richest families in the state.

Led by CARB, California’s regulatory bureaucracies have leveraged the state’s string of executive orders to pursue a climate agenda with little input from the legislature — often without express legislative authority, and at times imposing mandates that the legislature has itself repeatedly opposed. Newsom’s ICE executive order, for instance, followed the legislature’s decision to explicitly reject this mandate.

The resulting climate policies are rarely challenged by Black and Latino political leaders hailing from the same party, dependent on the same donor class, and acutely vulnerable to attacks from progressive environmentalists, who use low-turnout primaries to challenge them from the left should they question the climate dogma of White experts and advocates.

California’s climate agenda, in short, was constructed by White climate activists and donors, implemented by White governors and technocrats, in response to a crisis constructed by White scientists. What could possibly go wrong?

7.

“What’s White, Male, and 5 Feet Wide? Bay Area’s Bike Lanes,” the San Francisco Chronicle memorably quipped. While California’s environmental technocrats propose to herd its poor non-White residents into public transit they can’t use and high-density housing they can’t afford, they shower green subsidies upon the state’s wealthiest residents.

The state pays wealthy Californians to buy EVs and install rooftop solar with publicly funded subsidies and pours billions into transit extensions and bike lanes for well-to-do bedroom communities that hardly use them. Imagine if the state took the same approach to its wealthiest, Whitest residents as it does to its poorest communities of color. Climate equity demands that it should: wealthy households generate significantly more greenhouse gas emissions than average- and lower-income households. One study found that “high-income residents emit an average of 25% more GHG than low-income residents” and “high-emissions neighborhoods are primarily high income or extremely high income,” emitting up to 15 times more GHG than low-income neighborhoods.

One need not think long or hard to anticipate the backlash that would ensue if the state’s policy makers proposed a heavy carbon tax on homes larger than 2,000 square feet, required removal of gas cooktops and grills from homes valued over $1,000,000, or charged steep VMT fees for all miles driven in high VMT neighborhoods.

But unlike the communities of color most harmed by California’s housing and transportation policies, climate regulators are not demanding that rich White households sell their single-family homes, forgo cars to ride the bus, and eliminate their disproportionate use of aircraft.

The enormous subsidies necessary to coax the state’s wealthiest residents to go green belie claims made by California’s environmental elites that the state currently has, or soon will develop, the technology necessary to deeply cut emissions while equitably growing its economy.

The state may lead the world in renewable energy. But its electrical grid is a shambles. California is the most energy-efficient state in the nation, but that is primarily due to its temperate climate, expensive energy, and decades of deindustrialization, not green technology.

The state is still enormously wealthy. But economic growth in the Golden State in recent decades has been predominantly driven by the keyboard economy, entertainment, real estate, and tourism, which offer little opportunity for economic mobility for low-income communities of color.

Fifteen years after California embarked upon its present climate regime, there are finally signs that the state’s most vulnerable communities of color are less willing to defer to overwhelmingly White climate experts and continue to bear the disproportionate cost burdens imposed by California’s climate leaders. Black assembly member Jim Cooper has publicly demanded, “at the very least,” that White-led environmental groups and “policy making arms like CARB explain why they are promoting policies that systematically drive racial economic inequities and fuel environmental racism.” Latino voting rights advocates published a full-page response in the Los Angeles Times criticizing the Sierra Club’s efforts to “phase out” affordable cars in favor of “expensive EVs,” eliminate gas-powered “stoves, water heaters and furnaces” that require “us, or our landlords, to make investments we can’t afford,” and that make it possible for “our rich neighbors in the next town to charge their Teslas and run their air conditioners on hot days, but make it unaffordable to use ours.”

In late 2020, a group of veteran civil rights activists and former leaders of the state legislature, supreme court, and cabinet filed three lawsuits seeking to prevent CARB and other state agencies from pursuing racist climate housing and VMT policies. “CARB,” the group wrote to the agency in October 2020, “willfully elected to increase housing costs and make it more difficult for members of our communities to close the wealth gap with homeownership.” The group sharply criticized CARB’s unsuccessful legal defense that it was constitutional for CARB to engage in racially discriminatory climate policies because “housing was not a protected class.” The group has won one of the three lawsuits to mandate disclosure of documents. The other two remain pending — and are being fiercely contested by the state’s past and current progressive attorneys general.

Even usually docile regional and transportation planning agencies are starting to protest against the unjust racial consequences of California climate policies. “A slavish commitment to VMT reduction as the primary means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions,” the chair of the San Joaquin Council of Governments wrote in a December 2020 letter to CARB, “will prove self-defeating. . . . Local and regional leaders are not going to sign onto strategies that reduce economic growth and perpetuate social and economic inequalities to further VMT reductions.” After its catastrophically racist VMT housing maps, SCAG has made resolving the conflict between state climate policies and the need for housing one of its legislative priorities.

California’s leaders have attempted to divert attention from the growing inequity of the state’s climate agenda with transparently phony gestures toward woke sensibilities. But Black and Brown community leaders increasingly aren’t buying it. Mary Nichols, until recently the state’s celebrated climate czar, saw her hopes of being appointed to head the federal Environmental Protection Agency and take California’s climate agenda nationwide crumble after her tweet claiming that “‘I can’t breathe’ speaks to police violence, but it also applies to the struggle for clean air” sparked intense backlash from environmental justice advocates and Black state lawmakers. That tweet had been preceded by a decades-long pattern of prioritizing CARB-selected green technologies and practices favored by global climate advocates over the reduction of localized air pollution health impacts in communities of color.

8.

California provides compelling historical evidence that there are far more just alternatives to the state’s present racist climate policy regime. A generation ago, CARB itself led a war on smog in California that became a model for the nation. Between 1970 and 2017, according to the US Environmental Protection Agency, “aggregate national emissions of the six common pollutants alone dropped an average of 73 percent while gross domestic product grew by 324 percent.” In addition, “new cars, SUVs, and pickup trucks are 99 percent cleaner” than they were in 1970.

In Southern California, once the poster child for the nation’s polluted airways, ozone levels declined by five times from their postwar peaks. A bad air day today would barely register under the criteria used in prior decades.

California achieved these remarkable environmental accomplishments even as it grew to become the sixth largest economy in the world, built world-class educational facilities and infrastructure, and pioneered global advances in the media, communications, aerospace, biotechnology, computer technology, and agricultural industries.

The state did this by developing affordable and effective strategies to combat smog. Regulators continually experimented with and evaluated real-world outcomes and competing approaches for cleaning the air through technological innovations and practices, balanced with the need for continued economic growth.

Over the past 50 years, Clean Air Act standards under both federal and California law were informed by the social, technological, and economic trade-offs associated with various pollution reduction measures. Importantly, smog programs were altered when they were credibly linked with disproportionate burdens on communities of color. When it became clear that California’s “cash for clunkers” program, for instance, was allowing large industrial facilities to buy up affordable, high-polluting older vehicles used mostly by lower-income workers in communities of color, regulators modified the program.

Sadly, the same agency that once cleaned up the skies while creating historically unprecedented and equitable economic opportunity for all its residents is today characterized by dogmatism, arrogance, defensiveness, and obfuscation.

What would it look like for CARB to change course and apply successful lessons from its past success to tackle climate change?

First, the state needs to change its climate metrics to no longer credit California with GHG reductions when people and jobs leave for lower-cost states with higher per capita GHG emissions. Neither should it pretend that products made elsewhere and shipped to California have zero GHG while hammering away at industries providing good jobs to California’s communities of color with lower per-product GHG emissions than imported equivalents.

Second, the need to produce homes affordable for median-income families, without taxpayer subsidies or winning the lottery, is a moral imperative that has been broken by ill-considered regulatory mandates that increase housing costs without meaningfully reducing emissions. The California legislature already requires state building code standards to be neutral for residents — CARB and other state environmental agencies should apply the same principle to their climate mandates.

Third, the state needs to embrace the best available technology today, even if it’s not zero carbon and stop making ill-considered technology choices that continue to result in higher pollution impact in disadvantaged communities. CARB has rejected rules that would mandate trucks powered by compressed natural gas or biogas, technologies that are feasible today and would both substantially reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve air quality in low-income communities that are disproportionately affected by particulate air pollutants, in favor of an all-electric trucking fleet that is at best aspirational and may not be technically feasible at all in view of many experts. That’s absurd: we need to make meaningful incremental improvements to reduce GHG and improve air quality, just as we made incremental improvements to reduce smog — especially to reduce pollutant loads in disadvantaged communities.

Finally, the state needs to comply with existing legal mandates to provide affordable, reliable energy to Californians and stop pretending that existing solar, wind, and battery technologies can supply all or most of California’s energy needs, while the state closes its last nuclear plant and continues to grant license extensions to its dirtiest gas plants.

All of this is simply summarized as following the Clean Air Act’s successful regulatory pathway for reducing automobile smog by 99 percent: being methodical, transparent, and technology-neutral — and respectful of other moral and legal mandates, including civil rights.

My golden lottery ticket gave me a career at the intersection of environmental, land use, and civil rights laws. For the last 25 years, I have tried to pay my own good fortune forward, by advocating to close the racial wealth gap exacerbated by the anti-growth advocacy of environmental elites, and restoring attainable homeownership and upward mobility for tens of millions of people of color who have yet to realize the California Dream or even the possibility of a stable, working-class income with homeownership, like that achieved by my grandparents, my parents, and my own (Boomer) generation.

We are long overdue to reconsider California’s

racist, inequitable, and ineffectual climate agenda. There is no reason

the state could not continue to lead the world in reducing GHG emissions

with feasible, cost-effective technologies and racially equitable

strategies that can and would be widely replicated globally. Justice,

equity, and the climate all demand nothing less.

Jennifer Hernandez

is a Breakthrough Fellow, Board Member, and a California lawyer

practicing environmental, land use, and civil rights law. She has

received numerous civil rights awards for her work on overcoming

environmentalist opposition to housing and other projects needed and

supported by minority communities.

This article presents the

analysis and opinion of the author, and not her law firm or any other

party. The author represents one of the civil rights plaintiffs in

pending litigation challenging housing climate policies. Nothing herein

is intended to or does constitute legal advice.