The effects of climate change on human health include direct effects of extreme weather, leading to injury and loss of life, as well as indirect effects, such as undernutrition brought on by crop failures or a lack of access to safe drinking water. Climate change poses a wide range of risks to population health. The three main categories of health risks include: (i) direct-acting effects (e.g. due to heat waves, extreme weather disasters), (ii) impacts mediated via climate-related changes in ecological systems and relationships (e.g. crop yields, mosquito ecology, marine productivity), and (iii) the more diffuse (indirect) consequences relating to impoverishment, displacement, and mental health problems.

More specifically, the relationship between health and heat (increased global temperatures) includes the following aspects: exposure of vulnerable populations to heatwaves, heat-related mortality, impacts on physical activity and labour capacity and mental health. There is a range of climate-sensitive infectious diseases which may increase in some regions, such as mosquito-borne diseases, diseases from vibrio pathogens, cholera and some waterborne diseases. Health is also acutely impacted by extreme weather events (floods, hurricanes, droughts, wildfires) through injuries, diseases and air pollution in the case of wildfires. Other health impacts from climate change include migration and displacement due rising sea levels; food insecurity and undernutrition, reduced availability of drinking water, increased harmful algal blooms in oceans and lakes and increased ozone levels as an additional air pollutant during heatwaves. Available evidence on the effect of climate change on the epidemiology of snakebite is limited but it is expected that there will be a geographic shift in risk of snakebite: northwards in North America and southwards in South America and in Mozambique, and increase in incidence of bite in Sri Lanka.

The health impacts of climate change are felt around the world but disproportionately affect disadvantaged populations, making their climate change vulnerability worse, especially in developing countries. Young children are the most vulnerable to food shortages, and together with older people, to extreme heat.

The health effects of climate change are increasingly a matter of concern for the international public health policy community. Already in 2009, a publication in the well-known general medical journal The Lancet stated: "Climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century". This was re-iterated in 2015 by a statement of the World Health Organisation. In 2019, the Australian Medical Association formally declared climate change a health emergency.

Studies have found that communication on climate change is more likely to lead to engagement by the public if it is framed as a health concern, rather than just as an environmental matter. Health is one part of how climate change affects humans, together with aspects such as displacement and migration, security and social impacts.

Overview on causes and effects of climate change

In common usage, climate change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth's climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to Earth's climate. The current rise in global average temperature is more rapid than previous changes, and is primarily caused by humans burning fossil fuels. Fossil fuel use, deforestation, and some agricultural and industrial practices increase greenhouse gases, notably carbon dioxide and methane. Greenhouse gases absorb some of the heat that the Earth radiates after it warms from sunlight. Larger amounts of these gases trap more heat in Earth's lower atmosphere, causing global warming.

Due to climate change, deserts are expanding, while heat waves and wildfires are becoming more common. Increased warming in the Arctic has contributed to melting permafrost, glacial retreat and sea ice loss. Higher temperatures are also causing more intense storms, droughts, and other weather extremes. Rapid environmental change in mountains, coral reefs, and the Arctic is forcing many species to relocate or become extinct. Even if efforts to minimise future warming are successful, some effects will continue for centuries. These include ocean heating, ocean acidification and sea level rise.Types of pathways affecting health

Climate change is linked with health outcomes via three main pathways, mechanisms or risks:

- Direct mechanisms or risks: changes in extreme weather and resultant increased storms, floods, droughts, heat waves (wildfires also fit here)

- Indirect mechanisms or risks: these are mediated through changes in the biosphere (e.g., in the burden of disease and distribution of disease vectors, or food availability, water quality, air pollution, land use change, ecological change))

- Social dynamics (age and gender, health status, socioeconomic status, social capital, public health infrastructure, mobility and conflict status)

These health risks have "social and geographical dimensions, are unevenly distributed across the world, and are influenced by social and economic development, technology, and health service provision".

Overview of health impacts

General health impacts

The direct, indirect and social dynamic effects of climate change on health and wellbeing produce the following health impacts: cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, infectious diseases, undernutrition, mental illness, allergies, injuries and poisoning.

Health and health care provision can also be impacted by the collapse of health systems due to climate-induced disasters such as flooding. Therefore, building health systems that are climate resilient is a priority.

Mental health impacts

The effects of climate change on mental health and well-being can be rather negative, especially for vulnerable populations and those with pre-existing serious mental illness. There are three broad pathways by which these effects can take place: directly, indirectly or via awareness. The direct pathway includes stress related conditions being caused by exposure to extreme weather events, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Scientific studies have linked mental health outcomes to several climate-related exposures—heat, humidity, rainfall, drought, wildfires and floods. The indirect pathway can be via disruption to economic and social activities, such as when an area of farmland is less able to produce food. The third pathway can be of mere awareness of the climate change threat, even by individuals who are not otherwise affected by it.

Mental health outcomes have been measured in several studies through indicators such as psychiatric hospital admissions, mortality, self-harm and suicide rates. Vulnerable populations and life stages include people with pre-existing mental illness, Indigenous peoples, children and adolescents.

The emotional responses to the threat of climate change can include eco-anxiety, ecological grief and eco-anger. While unpleasant, such emotions are often not harmful, and can be rational responses to the degradation of the natural world, motivating adaptive action.

Assessing the exact mental health effects of climate change is difficult; increases in heat extremes pose risks to mental health which can manifest themselves in increased mental health-related hospital admissions and suicidality.Higher global temperatures and heat waves (direct risk)

Impacts of higher global temperatures will have ramifications for the following aspects: vulnerability to extremes of heat, exposure of vulnerable populations to heatwaves, heat and physical activity, change in labor capacity, heat and sentiment (mental health), heat-related mortality.

The global average and combined land and ocean surface temperature show a warming of 1.09 °C (range: 0.95 to 1.20 °C) from 1850–1900 to 2011–2020, based on multiple independently produced datasets. The trend is faster since 1970s than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2000 years.

Exposure of vulnerable populations to heatwaves

A sustained wet-bulb temperature exceeding 35 °C is a threshold at which the resilience of human systems is no longer able to adequately cool the skin. One study has concluded that even young, healthy people may be unable to maintain their core temperature within survivable limits at wet bulb temperatures above 31 °C.

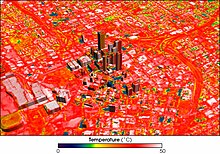

Another impact that the warming global temperature has had is on the frequency and severity of heat waves. The effects of heatwaves on human health are generally worse in urban areas, due to the "heat island" effect. The heat island effect is when urban areas experience much higher temperatures that surrounding rural environments. This is caused by the extensive areas of treeless asphalt, along with many large heat-retaining buildings that physically block cooling breezes.

The human response to heat stress can be hyperthermia, heat stroke and other harmful effects. Heat illness can relate to many of the organs and systems including: brain, heart, kidneys, liver, etc. Heat waves have also resulted in epidemics of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Recent studies have shown that prolonged heat exposure, physical exertion, and dehydration are sufficient factors to developing CKD. These cases are occurring across the world congruently with heat stress nephropathy.

A 2015 report revealed that the risk of dying from chronic lung disease during a heat wave was 1.8-8.2% higher compared to average summer temperatures. Bodily stress from heat also causes fluid loss, which disrupts pulmonary perfusion. In combination with higher pollutant concentrations, this leads to bronchial inflammation. A 2016 study found in people with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), increased indoor temperatures resulted in worsening breathlessness, cough, and sputum production. A 2009 study, conducted in New York, found a 7.6% increase in hospitalization rate for COPD patients for every 1 °C increase in temperatures above 29 °C.

The human body requires evaporative cooling to prevent overheating, even with a low activity level. With excessive ambient heat and humidity during heatwaves, adequate evaporative cooling might be compromised. Even under ideal conditions, sustained exposure to a wet-bulb temperature exceeding about 35 °C (95 °F) is fatal. As of 2020, only two weather stations had recorded 35 °C wet-bulb temperatures, and only very briefly, but the frequency and duration of these events is expected to rise with ongoing climate change. Elderly populations and those with co-morbidities are at a significantly increased health risk from increased heat.

Exposure to extreme heat "poses an acute health hazard, with individuals older than 65 years, populations in urban environments, and people with health conditions being particularly at risk".

A study that investigated 13,115 cities found that extreme heat exposure of a wet bulb globe temperature above 30 °C tripled between 1983 and 2016. It increased by ~50% when the population growth in these cities is not taken into account. Urban areas and living spaces are often significantly warmer than surrounding rural areas, partly due to the urban heat island effect.

Global warming is projected to substantially erode sleep worldwide, especially for residents from lower-income countries. The greatest increases of ambient temperatures were recorded at night.

Health experts warn that "exposure to extreme heat increases the risk of death from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory conditions and all-cause mortality. Heat-related deaths in people older than 65 years reached a record high of an estimated 345 000 deaths in 2019".

Increasing access to indoor cooling (air conditioning) will help prevent heat-related mortality but current air conditioning technology is generally unsustainable as it contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, peak electricity demand, and urban heat islands.

Heat and physical activity

High temperatures can reduce the frequency and duration of physical activity as well as the desire to engage in exercise.

The higher temperatures may have a substantial effect on human physiology and mental health. These effects may also be indirect: for example during the past four decades "the number of hours in which temperatures were too high for safe outdoor exercise" increased by an average loss of 3.7 hours for people in developing countries (low HDI country group).

Change in labour capacity

High temperatures can affect people's ability to work. Occupational heat exposure affects especially laborers in the agricultural sector of developing countries: It has been estimated that "295 billion hours of potential work were lost due to extreme heat exposure in 2020, with 79% of all losses in developing countries occurring in the agricultural sector."

Heat stress can lead to labor force productivity to decrease as well as participation because employees' health may be weaker due to heat related health problems. A study by NOAA from 2013 concluded that heat stress will reduce labor capacity considerably under current emissions scenarios.

Extreme weather events other than heatwaves (direct risk)

Infectious disease often accompanies extreme weather events, such as floods, earthquakes and drought. These local epidemics occur due to loss of infrastructure, such as hospitals and sanitation services, but also because of changes in local ecology and environment. For example, malaria outbreaks have been strongly associated with the El Niño cycles of a number of countries (India and Venezuela, for example). El Niño can lead to drastic, though temporary, changes in the environment such as temperature fluctuations and flash floods. Because of global warming there has been a marked trend towards more variable and anomalous weather. This has led to an increase in the number and severity of extreme weather events. This trend towards more variability and fluctuation is perhaps more important, in terms of its impact on human health, than that of a gradual and long-term trend towards higher average temperature.

Infectious disease often accompanies extreme weather events, such as floods, earthquakes and drought. Local epidemics occur due to loss of infrastructure, such as hospitals and sanitation services, but also because of changes in local ecology and environment.

Floods

Floods have short and long-term negative implications to people's health and well-being. Short term implications include mortalities, injuries and diseases, while long term implications include non-communicable diseases and psychosocial health aspects.

An example of this can likely be seen in the 2022 Pakistan Floods. The floods affected people’s health through various direct and indirect ways. Outbreaks of diseases like malaria, dengue, and other skin diseases.

Hurricanes and thunderstorms

Stronger hurricanes create more opportunities for vectors to breed and infectious diseases to flourish. Extreme weather also means stronger winds. These winds can carry vectors tens of thousands of kilometers, resulting in an introduction of new infectious agents to regions that have never seen them before, making the humans in these regions even more susceptible.

Another result of hurricanes is increased rainwater, which promotes flooding. Hurricanes result in ruptured pollen grains, which releases respirable aeroallergens. Thunderstorms cause a concentration of pollen grains at the ground level, which causes an increase in the release of allergenic particles in the atmosphere due to rupture by osmotic shock. Around 20–30 minutes after a thunderstorm, there is an increased risk for people with pollen allergies to experience severe asthmatic exacerbations, due to high concentration inhalation of allergenic peptides.

Climate change can affect tropical cyclones in a variety of ways: an intensification of rainfall and wind speed, a decrease in overall frequency, an increase in the frequency of very intense storms and a poleward extension of where the cyclones reach maximum intensity are among the possible consequences of human-induced climate change. Tropical cyclones use warm, moist air as their source of energy or "fuel". As climate change is warming ocean temperatures, there is potentially more of this fuel available. Between 1979 and 2017, there was a global increase in the proportion of tropical cyclones of Category 3 and higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale. The trend was most clear in the North Atlantic and in the Southern Indian Ocean. In the North Pacific, tropical cyclones have been moving poleward into colder waters and there was no increase in intensity over this period. With 2 °C (3.6 °F) warming, a greater percentage (+13%) of tropical cyclones are expected to reach Category 4 and 5 strength. A 2019 study indicates that climate change has been driving the observed trend of rapid intensification of tropical cyclones in the Atlantic basin. Rapidly intensifying cyclones are hard to forecast and therefore pose additional risk to coastal communities.

Warmer air can hold more water vapor: the theoretical maximum water vapor content is given by the Clausius–Clapeyron relation, which yields ≈7% increase in water vapor in the atmosphere per 1 °C (1.8 °F) warming. All models that were assessed in a 2019 review paper show a future increase of rainfall rates. Additional sea level rise will increase storm surge levels. It is plausible that extreme wind waves see an increase as a consequence of changes in tropical cyclones, further exacerbating storm surge dangers to coastal communities. The compounding effects from floods, storm surge, and terrestrial flooding (rivers) are projected to increase due to global warming.Droughts

Many of the consequences of droughts have impacts on human health. This can be through destruction of food supply (loss of crop yields), malnutrition and with this, dozens of associated diseases and health problems. Immune function decreases, so mortality rates due to infectious and other diseases climb. For those whose incomes were affected by droughts (namely agriculturalists and pastoralists), and for those who can barely afford the increased food prices, the cost to see a doctor or visit a clinic can simply be out of reach. Without treatment, some of these diseases can hinder one's ability to work, decreasing future opportunities for income and perpetuating the vicious cycle of poverty.

Climate change affects multiple factors associated with droughts, such as how much rain falls and how fast the rain evaporates again. Warming over land drives an increase in atmospheric evaporative demand which will increase the severity and frequency of droughts around much of the world. Scientists predict that in some regions of the world, there will be less rain in future due to global warming. These regions will therefore be more prone to drought in future: subtropical regions like the Mediterranean, southern Africa, south-western Australia and south-western South America, as well as tropical Central America, western Africa and the Amazon basin.

Physics dictates that higher temperatures lead to increased evaporation. The effect of this is soil drying and increased plant stress which will have impacts on agriculture. For this reason, even those regions where large changes in precipitation are not expected (such as central and northern Europe) will experience soil drying. The latest prediction of scientists in 2022 is that "If emissions of greenhouse gases are not curtailed, about a third of global land areas are projected to suffer from at least moderate drought by 2100". When droughts occur they are likely to be more intense than in the past.Wildfires

Climate change increases wildfire potential and activity. Climate change leads to a warmer ground temperature and its effects include earlier snowmelt dates, drier than expected vegetation, increased number of potential fire days, increased occurrence of summer droughts, and a prolonged dry season.

Warming spring and summer temperatures increase flammability of materials that make up the forest floors. Warmer temperatures cause dehydration of these materials, which prevents rain from soaking up and dampening fires. Furthermore, pollution from wildfires can exacerbate climate change by releasing atmospheric aerosols, which modify cloud and precipitation patterns.

Wood smoke from wildfires produces particulate matter that has damaging effects to human health. The primary pollutants in wood smoke are carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. Through the destruction of forests and human-designed infrastructure, wildfire smoke releases other toxic and carcinogenic compounds, such as formaldehyde and hydrocarbons. These pollutants damage human health by evading the mucociliary clearance system and depositing in the upper respiratory tract, where they exert toxic effects.

The health effects of wildfire smoke exposure include exacerbation and development of respiratory illness such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; increased risk of lung cancer, mesothelioma and tuberculosis; increased airway hyper-responsiveness; changes in levels of inflammatory mediators and coagulation factors; and respiratory tract infection. It may also have intrauterine effects on fetal development, resulting in low birth weight newborns. Because wildfire smoke travels and is often not isolated to a single geographic region, the health effects are widespread among populations.

Climate-sensitive infectious diseases (indirect risk)

Climate change is affecting the distribution of arthropodborne diseases (transmitted via mosquitos, ticks etc.), food-borne, and water-borne diseases. Climate change results in changes to the climate suitability for infectious disease transmission as well as vulnerability to mosquito-borne diseases. Warming oceans and a changing climate result in extreme weather patterns which have brought about an increase of infectious diseases—both new and re-emerging.

Climate change may also lead to new infectious diseases due to changes in microbial and vector geographic range. Microbes that are harmful to humans can adapt to higher temperatures, which will allow them to build better tolerance against human endothermy defenses.

Global climate change has resulted in a wide range of impacts on the spread of infectious diseases. Like other climate change impacts on human health, climate change exacerbates existing inequalities and challenges in managing infectious disease. It also increases the likelihood of certain kinds of new infectious disease challenges. Infectious diseases whose transmission can be impacted by climate change include Dengue fever, Malaria, Tick-borne disease, Leishmaniasis, Ebola. There is no direct evidence that the spread of COVID-19 is worsened or is caused by climate change, although investigations continue.

Documented infectious disease impacts of climate change, include increased malaria and dengue, which are expected to worsen as the global climate changes directly result in extreme weather conditions and higher temperatures. Not only will it propagate their spread, but climate change will probably bring forth new infectious diseases, and change the epidemiology of many existing diseases. Climate change increases pandemic risks.Mosquito-borne diseases

Mosquito-borne diseases are probably the greatest threat to humans as they include malaria, elephantiasis, Rift Valley fever, yellow fever, and dengue fever. Studies are showing higher prevalence of these diseases in areas that have experienced extreme flooding and drought. Flooding creates more standing water for mosquitoes to breed; as well, shown that these vectors are able to feed more and grow faster in warmer climates. As the climate warms over the oceans and coastal regions, warmer temperatures are also creeping up to higher elevations allowing mosquitoes to survive in areas they had never been able to before. As the climate continues to warm there is a risk that malaria will make a return to the developed world.

Increased heat, generated by the buildup of carbon, has been found to help disease-carrying organisms such as mosquitos thrive by producing stable environments for them. A research organization known as Climate Central states "The land area of the U.S. most suitable for Aedes albopictus mosquitoes is projected to increase from 5 percent to about 50 percent by 2100, putting 60 percent of the northeastern U.S.' population at risk for the diseases carried by this mosquito, including West Nile virus, dengue and Zika." An outbreak of diseases like the West Nile and Zika virus could trigger a crisis since it would cause severe illness in people as well as birth defects in infants. Less advanced countries would be especially affected as they may have very limited resources to combat an infestation.

Diseases from vibrio pathogens

The area of coastline with suitable conditions for vibrio bacteria has increased due changes in sea surface temperature and sea surface salinity caused by climate change. These pathogens can cause gastroenteritis, cholera, wound infections, and sepsis. It has been observed that in the period of 2011–21, the "area of coastline suitable for Vibrio bacterial transmission has increased by 35% in the Baltics, 25% in the Atlantic Northeast, and 4% in the Pacific Northwest.

Cholera

The warming oceans are leading to more frequent cholera. As the nitrogen and phosphorus levels in the oceans increase, the cholera bacteria that lives within zooplankton emerge from their dormant state. The changing winds and changing ocean currents push the zooplankton toward the coastline, carrying the cholera bacteria, which then contaminate drinking water, causing cholera outbreaks. As flooding increases there is also an increase in cholera epidemics as the flood waters that are carrying the bacteria are infiltrating the drinking water supply. El Nino has also been linked with cholera outbreaks because this weather pattern warms the shoreline waters, causing the cholera bacteria to multiply rapidly.

Parasites in warmer freshwater

Warmer freshwater due to global warming is increasing the presence of the amoeba Naegleria fowleri, in freshwater and the parasite Cryptosporidium in pools, and both can cause a severe disease.

Zoonotic diseases

Climate change can facilitate outbreaks of zoonoses, i.e. diseases that pass from animals to humans. One example of such outbreaks is the COVID-19 pandemic.

With regards to zoonotic diseases (e.g., diseases that pass from animals to humans), deforestation, climate change, and livestock agriculture are among the main causes of increased disease risk. As of 2016, outbreaks have cost lives and financial losses amounting to billions of dollars; future pandemics could cost trillions of dollars.

It is projected that interspecies viral sharing, that can lead to novel viral spillovers, will increase due to ongoing climate change-caused geographic range-shifts of mammals (most importantly bats). Risk hotspots would mainly be located at "high elevations, in biodiversity hotspots, and in areas of high human population density in Asia and Africa".

Diseases from ticks

Ticks are also thriving in the warmer temperatures allowing them to feed and grow at a faster rate. The black legged tick, a carrier of Lyme disease, when not feeding, spends its time burrowed in soil absorbing moisture. Ticks die when the climate either becomes too cold or when the climate becomes too dry, causing the ticks to dry out. The natural environmental controls that used to keep the tick populations in check are disappearing, and warmer and wetter climates are allowing the ticks to breed and grow at an alarming rate, resulting in an increase in Lyme disease, both in existing areas and in areas where it has not been seen before.

Other infectious diseases

Other diseases on the rise due to extreme weather include hantavirus, schistosomiasis, onchocerciasis (river blindness), and tuberculosis. It also causes the rise in hay fever, as when the weather gets warmer there is a rise in pollen levels in the air.

Food and drinking water availability (indirect risk)

Food insecurity and undernutrition

Climate change has impacts on terrestrial and marine food security and undernutrition. Food insecurity is increasing (some of the underlying causes are related to climate change, for example an increase in extreme weather events, pests and pathogens) and has affected 2 billion people in 2019.

Terrestrial food insecurity

Over 500,000 more adult deaths are projected yearly by 2050 due to reductions in food availability and quality due to climate change.

Changes in atmospheric carbon dioxide may reduce the nutritional quality of some crops. Elevated CO2 may reduce the nutritional values of crops, with for instance wheat having less protein and less of some minerals. Studies have shown that increases in CO2 lead to decreased concentrations of micronutrients in crop and non-crop plants with negative consequences for human nutrition, including decreased B vitamins in rice.

Climate change induced drought stress in Africa will likely lead to a reduction in the nutritional quality of the common bean. Studies have also shown that higher CO2 levels lead to reduced plant uptake of nitrogen (and a smaller number showing the same for trace elements such as zinc) resulting in crops with lower nutritional value. This would primarily impact on populations in poorer countries less able to compensate by eating more food, more varied diets, or possibly taking supplements.

Marine food insecurity

A headline finding in 2021 regarding marine food security stated that: "In 2018–20, nearly 70% of countries showed increases in average sea surface temperature in their territorial waters compared within 2003–05, reflecting an increasing threat to their marine food productivity and marine food security".

With seafood being a major protein source for so much of the population, there are inherent health risks associated with climate change. Increased agricultural runoff and warmer water temperature allows for eutrophication of ocean waters. This increased growth of algae and phytoplankton in turn can have dire consequences. These algal blooms can emit toxic substances that can be harmful to humans if consumed. Organisms, such as shellfish, marine crustaceans and even fish, feed on or near these infected blooms, ingest the toxins and can be consumed unknowingly by humans.

Reduced availability of drinking water

As the climate warms, it changes the nature of global rainfall, evaporation, snow, stream flow and other factors that affect water supply and quality. Rising sea levels cause saltwater to enter into fresh underground water and freshwater streams. This reduces the amount of freshwater available for drinking and farming.

Fifty percent of the world's fresh water consumption is dependent glacial runoff. Earth's glaciers are expected to melt within the next forty years, greatly decreasing fresh water flow in the hotter times of the year, causing everyone to depend on rainwater, resulting in large shortages and fluctuations in fresh water availability which largely effects agriculture, power supply, and human health and well-being. Many power sources and a large portion of agriculture rely on glacial runoff in the late summer. "In many parts of the world, disappearing mountain glaciers and droughts will make fresh, clean water for drinking, bathing, and other necessary human (and livestock) uses scarce" and a valuable commodity.

Water management

Climate change poses a threat to our current systems for water management, which in turn poses a threat to the availability of drinking water. Traditional water management systems use rely heavily on the assumption of stationarity. Stationarity in water management is "the idea that natural systems fluctuate within an unchanging envelope of variability." The significant anthropogenically induced change in Earth's climate has altered hydrologic stationarity, changing the means and extremes of precipitation, evapotranspiration, and river discharge rates. Traditionally, water plans are based on historic data, such as streamflow data and historic precipitation rates. With the variability of climate change, many of these models are rendered ineffective. For example, in the Colorado basin, there has been an observed increase in high and low stream flow by 24% when compared to historic data. This increase variability in the water cycle has the potential to render traditional methods of water planning and management ineffective, leading to shortage of drinking water supply.

Water quality

Water quality can be affected by climate change in several ways. In some regions, climate change will drive an increase in precipitation. The increasing volume of water has the potential to overwhelm sewer systems and water treatment plants, resulting in contaminated water entering municipal water supplies. Moreover, heavy downpours can increase runoff into surface water bodies. Runoff contaminants may include sediments, nutrients, pollutants, animal excrement, and other harmful materials. The increase in runoff into surface waters can result in a degradation of water quality. In addition, freshwater resources along the coastline are at risk of saltwater contamination. As the sea level rises with climate change, saltwater will move into freshwater areas, contaminating drinking water supplies. Moreover, the increase in water consumption in regions of drought can cause salt waters to infiltrate further upstream as freshwater is drained from rivers and reservoirs upstream. The increase in droughts can lead to saltwater contamination in once-reliable freshwater sources.

Water treatment

In areas of increased flooding and precipitation, water treatment plants will not be able to keep up with the increased water volume, leading to contamination. On the other end of the spectrum, the increase in droughts and temperatures can result in lower streamflow, therefore treatment will have to be increased to meet minimum flow requirements in some regions. On top of this, rising sea levels from climate change can damage infrastructure and reduce treatment efficiency. As water treatment becomes less effective, water-borne diseases will become more prevalent.

Climate change increases the risk of illness via "increasing temperature, more frequent heavy rains and runoff, and the effects of storms".

Displacement and migration (social dynamics)

Humanitarian crises are increasingly impacted by climate change in areas where climate hazards interact with high climate change vulnerability. Climate change is driving displacement throughout all regions of the world, but small island states have been disproportionately affected. In areas such as Africa, Central, and South America, flood and drought-related food insecurities have increased.

Warming above 1.5 degrees can make tropical regions uninhabitable, because the threshold of 35 degrees of wet bulb temperature (the limit of human adaptation to heat and humidity), will be passed. 43% of the human population live in the tropics.

Other health risks from climate change

Harmful algal blooms in oceans and lakes

The warming oceans and lakes are leading to more frequent harmful algal blooms. Also, during droughts, surface waters are even more susceptible to harmful algal blooms and microorganisms. Algal blooms increase water turbidity, suffocating aquatic plants, and can deplete oxygen, killing fish. Some kinds of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) create neurotoxins, hepatoxins, cytotoxins or endotoxins that can cause serious and sometimes fatal neurological, liver and digestive diseases in humans. Cyanobacteria grow best in warmer temperatures (especially above 25 degrees Celsius), and so areas of the world that are experiencing general warming as a result of climate change are also experiencing harmful algal blooms more frequently and for longer periods of time.

One of these toxin producing algae is Pseudo-nitzschia fraudulenta. This species produces a substance called domoic acid which is responsible for amnesic shellfish poisoning. The toxicity of this species has been shown to increase with greater CO2 concentrations associated with ocean acidification. Some of the more common illnesses reported from harmful algal blooms include; Ciguatera fish poisoning, paralytic shellfish poisoning, azaspiracid shellfish poisoning, diarrhetic shellfish poisoning, neurotoxic shellfish poisoning and the above-mentioned amnesic shellfish poisoning.

Ozone as an air pollutant

Ozone pollution in urban areas is especially concerning with increasing temperatures, raising heat-related mortality during heat waves. During heat waves in urban areas, ground level ozone pollution can be 20% higher than usual.

One study concluded that from 1860 to 2000, the global population-weighted fine particle concentrations increased by 5% and near-surface ozone concentrations by 2% due to climate change.

Ozone pollution has many well-known health effects:

- Ozone can cause adverse effects to the respiratory system such as shortness of breath and inflammation of the airways in the general population

- Long term exposure to ozone is likely one of the many causes of asthma development

- Ozone exposure is a potential cause of premature deaths

Carbon dioxide levels and human cognition

Higher levels of indoor and outdoor CO2 levels may impair human cognition.

Drowning accidents from higher winter temperatures

Researchers found that there is a strong correlation between higher winter temperatures and drowning accidents in large lakes, because the ice gets thinner and weaker.

Pollen allergies

A minor further effect are increases of pollen season lengths and concentrations in some regions of the world which can affect people with pollen allergies.

Armed conflicts induced by climate hazards

Climate change may have influence on the risk of violent conflict, including organized armed conflict. Evidence shows links between armed conflict and variations in temperature: conflict incidence substantially increases during warmer periods. Climate change is predicted to diminish natural resource availability. Water scarcity, food shortages, and decreased livelihoods may lead to an increase in desperate populations, enhancing the risk of intra and interstate conflicts. Climate hazards are a driving force of involuntary migration with a growing impact and a potentially important contributor to violent conflicts even though the importance is small compared to other factors such as culture, politics, and economy. Climate hazards are associated with increased violence against vulnerable groups and the mitigation could potentially exacerbate violent conflicts. Future increases in violent-conflict-related deaths induced by climate change have been estimated at conflict-prone regions.

Potential health benefits

Health co-benefits from mitigation and adaptation

The health benefits (also called "co-benefits") from climate change mitigation measures are predicted to be signification: potential measures can not only mitigate future health impacts from climate change but also improve health directly. Climate change mitigation is interconnected with various co-benefits (such as reduced air pollution and associated health benefits) and how it is carried out (in terms of e.g. policymaking) could also determine its impacts on living standards (whether and how inequality and poverty are reduced).

There are many health co-benefits associated with climate action. These include those of cleaner air, healthier diets (e.g. less red meat), more active lifestyles, and increased exposure to green urban spaces. Access to urban green spaces provides benefits to mental health as well.

Compared with the current pathways scenario (with regards to greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation efforts), the "sustainable pathways scenario" will likely result in an annual reduction of 1.18 million air pollution-related deaths, 5.86 million diet-related deaths, and 1.15 million deaths due to physical inactivity, across the nine countries, by 2040. These benefits were attributable to the mitigation of direct greenhouse gas emissions and the commensurate actions that reduce exposure to harmful pollutants, as well as improved diets and safe physical activity. Air pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion is both a major driver of global warming and the cause of a large number of annual deaths with some estimates as high as 8.7 million excess deaths during 2018.

Placing health as a key focus of the Nationally Determined Contributions could present an opportunity to increase ambition and realize health co-benefits. Some politicians, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger with his slogan "terminate pollution", say that activists should generate optimism by focusing on the health co-benefits of climate action.

Potential health benefits from global warming

It has been projected that climate change will bring some benefits in temperate areas, such as fewer deaths from cold exposure, and some mixed effects such as changes in range and transmission potential of malaria in Africa. Benefits are projected to be outweighed by negative health effects of rising temperatures, especially in developing countries.

Global estimates

In 2021 more than 230 medical journals issued a statement saying that climate change already severely hurts human health, including by: "an increase in heat deaths, dehydration and kidney function loss, skin cancer, tropical infections, mental health issues, pregnancy complications, allergies, and heart and lung disease, and deaths associated with them". A 1.5 degree temperature rise with biodiversity loss will cause a catastrophic damage. They called to not allow such temperature rise and stop biodiversity loss.

Estimating deaths (mortality) or DALYs (morbidity) from the effects of climate change at the global level is very difficult. A 2014 study by the World Health Organization tried to do this and estimated the effect of climate change on human health, but not all of the effects of climate change were included in their estimates. For example, the effects of more frequent and extreme storms were excluded. They did assess deaths from heat exposure in elderly people, increases in diarrhea, malaria, dengue, coastal flooding, and childhood undernutrition. The authors estimated that climate change was projected to cause an additional 250,000 deaths per year between 2030 and 2050 but also stated that "these numbers do not represent a prediction of the overall impacts of climate change on health, since we could not quantify several important causal pathways". A 2021 study found that climate change is responsible for 5 million excess deaths annually worldwide. Another 2021 study estimated 9 million to 83 million excess deaths from climate change between 2020 and 2100, depending on the amount of greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate change was responsible for 3% of diarrhoea, 3% of malaria, and 3.8% of dengue fever deaths worldwide in 2004. Total attributable mortality was about 0.2% of deaths in 2004; of these, 85% were child deaths. The effects of more frequent and extreme storms were excluded from this study.

Policy responses

Due to its significant impact on human health, climate change has become a major concern for public health policy. The United States Environmental Protection Agency had issued a 100-page report on global warming and human health back in 1989. By the early years of the 21st century, climate change was increasingly addressed as a public health concern at a global level, for example in 2006 at Nairobi by UN secretary general Kofi Annan. Since 2018, factors such as the 2018 heat wave, the Greta effect and the October 2018 IPPC 1.5 °C report further increased the urgency for responding to climate change as a global health issue.

While a matter of international and national concern, health impacts from climate change have been described as "inherently local". For example, a city may be adjacent to the sea and suffer a heat island effect, so may have considerably different climate related health concerns to a nearby small town located only 20 miles inland. The health impact of climate change are expected to rise in line with predicted ongoing global warming.

The 2015 Lancet "Commission on Health and Climate Change" concluded that "tackling climate change could be the greatest global health opportunity of this century".

Economic development is an important component of possible adaptation to climate change. Economic growth on its own, however, is not sufficient to insulate the world's population from disease and injury due to climate change. Future vulnerability to climate change will depend not only on the extent of social and economic change, but also on how the benefits and costs of change are distributed in society. For example, in the 19th century, rapid urbanization in western Europe led to health plummeting. Other factors important in determining the health of populations include education, the availability of health services, and public-health infrastructure.

Climate-sensitive health system resilience

The World Bank suggested that climate-sensitive health system resilience should be increased through investment in two areas:

- Health system strengthening to improve resilience and build capacity to prepare for the varied environmental impacts and health impacts caused by climate change (for example early warning systems, disaster preparedness systems); and

- Programmatic (e.g., disease-specific, nutrition-focused) responses to address the changing burden of disease related to climate change.

Society and culture

Health equity and climate justice

Much of the health burden associated with climate change falls on vulnerable people (e.g. coastline inhabitants, indigenous peoples, economically disadvantaged communities). As a result, people of disadvantaged sociodemographic groups experience unequal risks. Often these people will have made a disproportionately low contribution toward man-made global warming, thus leading to concerns over climate justice. Climate change can worsen the existing, often enormous, health problems, especially in the poorer parts of the world.

Notably, in the United States, housing policy and zoning laws have historically limited the opportunity for minority populations to seek places of living. The common options are often areas with a disproportionately higher risk of exposure to environmental hazards. These environmental hazards are compounded by the growing effects of climate change and air pollution, resulting in a higher chance of adverse impacts on minority populations. These communities have the highest estimated temperature-related deaths, heat-related illnesses, pesticide exposure, and childhood asthma diagnosis. Furthermore, this leads to inequitable health outcomes regarding climate change and air pollution. There is not only an equity issue with the systems and infrastructure that restrict minority populations to more high-risk living areas but also with the emergency response. More affluent and white communities are afforded a more prompt emergency response following a climate or environmental crisis. Too often, communities with minority populations are not afforded this rapid emergency response and even have to wait until the issue stockpiles into an even larger tragedy.

Climate communication

Studies have found that when communicating climate change with the public, it can help encourage engagement if it is framed as a health concern, rather than as an environmental issue. This is especially the case when comparing a health related framing to one that emphasised environmental doom, as was common in the media at least up until 2017.