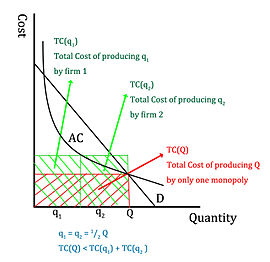

A natural monopoly is a monopoly in an industry in which high infrastructural costs and other barriers to entry relative to the size of the market give the largest supplier in an industry, often the first supplier in a market, an overwhelming advantage over potential competitors. Specifically, an industry is a natural monopoly if the total cost of one firm, producing the total output, is lower than the total cost of two or more firms producing the entire production. In that case, it is very probable that a company (monopoly) or minimal number of companies (oligopoly) will form, providing all or most relevant products and/or services. This frequently occurs in industries where capital costs predominate, creating large economies of scale about the size of the market; examples include public utilities such as water services, electricity, telecommunications, mail, etc. Natural monopolies were recognized as potential sources of market failure as early as the 19th century; John Stuart Mill advocated government regulation to make them serve the public good.

Definition

Two different types of cost are important in microeconomics: marginal cost, and fixed cost. The marginal cost is the cost to the company of serving one more customer. In an industry where a natural monopoly does not exist, the vast majority of industries, the marginal cost decreases with economies of scale, then increases as the company has growing pains (overworking its employees, bureaucracy, inefficiencies, etc.). Along with this, the average cost of its products decreases and increases. A natural monopoly has a very different cost structure. A natural monopoly has a high fixed cost for a product that does not depend on output, but its marginal cost of producing one more good is roughly constant, and small.

It is generally believed that there are two reasons for natural monopolies: one is economies of scale, and the other is economies of scope.

All industries have costs associated with entering them. Often, a large portion of these costs is required for investment. Larger industries, like utilities, require an enormous initial investment. This barrier to entry reduces the number of possible entrants into the industry regardless of the earning of the corporations within. The production cost of an enterprise is not fixed, except for the effect of technology and other factors; even under the same conditions, the unit production cost of an enterprise can also tend to decrease with the increase in the total production output. The reason is that the actual product of the enterprise As it continues to expand, the original fixed costs are gradually diluted. This is particularly evident in companies with significant fixed-cost investments. Natural monopolies arise where the largest supplier in an industry, often the first supplier in a market, has an overwhelming cost advantage over other actual or potential competitors; this tends to be the case in industries where fixed costs predominate, creating economies of scale that are large in relation to the size of the market, as is the case in water and electricity services. The fixed cost of constructing a competing transmission network is so high, and the marginal cost of transmission for the incumbent so low, that it effectively bars potential competitors from the monopolist's market, acting as a nearly insurmountable barrier to entry into the market place.

A firm with high fixed costs requires a large number of customers in order to have a meaningful return on investment. This is where economies of scale become important. Since each firm has large initial costs, as the firm gains market share and increases its output the fixed cost (what they initially invested) is divided among a larger number of customers. Therefore, in industries with large initial investment requirements, average total cost declines as output increases over a much larger range of output levels.

In real life, companies produce or provide single goods and services but often diversify their operations. Suppose the cost of having multiple products by one enterprise is lower than making them separately by several enterprises. In that case, it indicates that there is an economy of scope. Since the unit product price of a company that produces a specific product alone is higher than the corresponding unit product price of a joint production company, the companies that make it separately will lose money. These companies will either withdraw from the production field or be merged, forming a monopoly. Therefore, well-known American economists Samuelson and Nordhaus pointed out that economies of scope can also produce natural monopolies.

Companies that take advantage of economies of scale often run into problems of bureaucracy; these factors interact to produce an "ideal" size for a company, at which the company's average cost of production is minimized. If that ideal size is large enough to supply the whole market, then that market is a natural monopoly.

Once a natural monopoly has been established because of the large initial cost and that, according to the rule of economies of scale, the larger corporation (to a point) has a lower average cost and therefore an advantage over its competitors. With this knowledge, no firms will attempt to enter the industry and an oligopoly or monopoly develops.

Formal definition

William Baumol (1977) provides the current formal definition of a natural monopoly. He defines a natural monopoly as "[a]n industry in which multi-firm production is more costly than production by a monopoly" (p. 810). Baumol linked the definition to the mathematical concept of subadditivity; specifically, subadditivity of the cost function. Baumol also noted that for a firm producing a single product, scale economies were a sufficient condition but not a necessary condition to prove subadditivity, the argument can be illustrated as follows:

Proposition: Strict economies of scale are sufficient but not necessary for ray average cost to be strictly declining.

Proposition: Strictly declining ray average cost implies strict ray subadditivity.

Proof

Proposition: Neither ray concavity nor ray average costs that decline everywhere are necessary for strict subadditivity.

Proof

Combining all propositions gives:

Proposition: Global scale economies are sufficient but not necessary for (strict) ray subadditivity, the condition for natural monopoly in the production of a single product or in any bundle of outputs produced in fixed proportions.

Multiproduct case

On the other hand if firms produce many products scale economies are neither sufficient nor necessary for subadditivity:

Proposition: Strict concavity of a cost function is not sufficient to guarantee subadditivity.

Proof

Therefore:

Proposition: Scale economies are neither necessary nor sufficient for subadditivity.

Mathematical Notation of Subadditivity

A cost function c is subadditive at an output x if such that , with all x being non-negative. In other words, if all companies have the same production cost function, the one with the better technology should monopolize the entire market such that the total cost is minimized, thus causing natural monopoly due to its technological advantage or condition.

Examples

- Railways:

The costs of laying tracks and building networks coupled with that of buying or leasing the trains prohibits or deters the entry of any competitor. Rail transport also fits other characteristics of a natural monopoly because it is assumed to be an industry with significant long run economies of scale. - Telecommunications and Utilities:

The costs of building telecommunication poles and growing a cell network would just be too exhausting for other competitors to exist. Electricity requires grids and cables whilst water services and gas both require pipelines whose costs are just too high to be able to have existing competitors in the public market. However, natural monopolies are usually regulated and they face increasing competition from private networks and specialty carriers.

History

The development of the concept of natural monopoly is often attributed to John Stuart Mill, who (writing before the marginalist revolution) believed that prices would reflect the costs of production in absence of an artificial or natural monopoly. In Principles of Political Economy Mill criticised Smith's neglect of an area that could explain wage disparity (the term itself was already in use in Smith's times, but with a slightly different meaning). Taking up the examples of professionals such as jewellers, physicians and lawyers, he said,

The superiority of reward is not here the consequence of competition, but of its absence: not a compensation for disadvantages inherent in the employment, but an extra advantage; a kind of monopoly price, the effect not of a legal, but of what has been termed a natural monopoly... independently of... artificial monopolies [i.e. grants by government], there is a natural monopoly in favour of skilled labourers against the unskilled, which makes the difference of reward exceed, sometimes in a manifold proportion, what is sufficient merely to equalize their advantages.

Mill's initial use of the term concerned natural abilities. In contrast, common contemporary usage refers solely to market failure in a particular type of industry such as rail, post or electricity. Mill's development of the idea that 'what is true of labour, is true of capital'. He continues;

All the natural monopolies (meaning thereby those which are created by circumstances, and not by law) which produce or aggravate the disparities in the remuneration of different kinds of labour, operate similarly between different employments of capital. If a business can only be advantageously carried on by a large capital, this in most countries limits so narrowly the class of persons who can enter into the employment, that they are enabled to keep their rate of profit above the general level. A trade may also, from the nature of the case, be confined to so few hands, that profits may admit of being kept up by a combination among the dealers. It is well known that even among so numerous a body as the London booksellers, this sort of combination long continued to exist. I have already mentioned the case of the gas and water companies.

Mill also applied the term to land, which can manifest a natural monopoly by virtue of it being the only land with a particular mineral, etc. Furthermore, Mill referred to network industries, such as electricity and water supply, roads, rail and canals, as "practical monopolies", where "it is the part of the government, either to subject the business to reasonable conditions for the general advantage or to retain such power over it, that the profits of the monopoly may at least be obtained for the public." So, a legal prohibition against non-government competitors is often advocated. Whereby the rates are not left to the market but are regulated by the government; maximising profits, and subsequently societal reinvestment.

For a discussion of the historical origins of the term 'natural monopoly' see Mosca.

Regulation

As with all monopolies, a monopolist that has gained its position through natural monopoly effects may engage in behaviour that abuses its market position. In cases where exploitation occurs, it often leads to calls from consumers for government regulation. Government regulation may also come about at the request of a business hoping to enter a market otherwise dominated by a natural monopoly.

Common arguments in favour of regulation include the desire to limit a company's potentially abusive or unfair market power, facilitate competition, promote investment or system expansion, or stabilise markets. This is especially true in the case of essential utilities like electricity where a monopoly creates a captive market for a product few can refuse. In general, though, regulation occurs when the government believes that the operator, left to his own devices, would behave in a way that is contrary to the public interest. In some countries an early solution to this perceived problem was government provision of, for example, a utility service. Enabling a monopolistic company with the ability to change prices without regulation can have devastating effects in society. Ramifications of which can be displayed in Bolivia’s 2000 Cochabamba protests. A situation whereby a firm with a monopoly on the supply of water, excessively increased water rates to fund a dam; leaving many unable to afford the essential good.

History

A wave of nationalisation across Europe after World War II created state-owned companies in each of these areas, many of which operate internationally bidding on utility contracts in other countries. However, this approach can raise its own problems. In the past, some governments have used the state-provided utility services as a source of cash flow for funding other government activities, or as a means of obtaining hard currency. As a result, governments seeking funding began to seek other solutions, namely regulation and providing services on a commercial basis, often through private participation.

In recent years, bodies of information have observed the correlation between utility subsidies and welfare improvements. Today, across the world, public utilities are widely used to provide state-run water, electricity, gas, telecommunications, mass-transportation and postal services.

Alternative regulation

Alternatives to a state-owned response to natural monopolies include both open source licensed technology and co-operatives management where a monopoly's users or workers own the monopoly. For instance, the web's open-source architecture has both stimulated massive growth and avoided a single company controlling the entire market. The Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation is an American co-op that provides the majority of clearing and financial settlement across the securities industry ensuring they cannot abuse their market position to raise costs. In recent years a combined cooperative and open-source alternative to emergent web monopolies has been proposed, a platform cooperative, where, for instance, Uber could be a driver-owned cooperative developing and sharing open-source software.