CFS is preventing the mass approval of GMO crops and foods! We’re in court fighting some of our earth’s biggest polluters: Monsanto, Dow Chemical, and the agency that gives a green light to these polluters—the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) …. Our team is here to stop the use of dangerous pesticides that threaten our health and the health of our planet. If we work together, we can stop the next generation of dangerous GMO crops!

Bayer’s decision in June to settle some 95,000 lawsuits alleging its Roundup weedkiller causes cancer for $10.9 billion is perhaps the best indicator of how effective this litigation strategy is. The settlement, one of the largest in US history, was Bayer’s way of putting the breaks on a legal fight that was crippling it financially, though it appears the biotech giant may still have to defend its flagship weedkiller against many more plaintiffs after part of the deal fell through. In mid-July, the company also lost an appeal in the first Roundup case that went to trial, a 2018 suit brought by a California groundskeeper.

What’s emerging from the chaos of years of litigation targeting Monsanto (now owned by Bayer) and other makers of agricultural chemicals is that industry antagonists are not finished. Advocacy anti-GMO groups, now partnered with the tort industry, are poised to go after other chemicals in the conventional agricultural toolbox, including other herbicides, insecticides and synthetic fertilizers.

Just last week, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled that the family of golf course groundskeeper Thomas Walsh could proceed with its civil case against a dozen major chemical manufacturers for allegedly causing his leukemia and eventual death. Glyphosate is technically not on trial here, as it has not been linked in any studies to leukemia. But a handful of studies have shown some correlation between glyphosate and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in long-term users, while the vast majority of studies have not confirmed any links. Rather, the focus will be on a range of other chemicals used to control pests.

Beyond glyphosate

Success breeds copycats, and the windfall generated by anti-biotechnology activism has primed the litigation pump. Since many popular weedkillers are paired with genetically engineered crops that resist their herbicidal effects, activist groups or trial lawyers they work with are filing a slew of lawsuits alleging that other pesticides pose serious risks to human health or the environment. Their goal is to force the manufacturers to pull their products off the market or get the EPA to ban them. Eliminate the pesticides and farmers have no incentive to plant the herbicide-resistant seeds.

Environmental groups led by CFS have recently convinced a federal court to ban another popular herbicide, drift-prone dicamba, and are trying to get the same circuit court to vacate the registration for Enlist weedkillers sold by Corteva Agriscience. Activist groups are also agitating to block EPA approval of Bayer’s new corn variety that withstands exposure to five different herbicides. True to form, CFS executive director Andrew Kimbrell said victory in these suits could “massively reduce” the use of GMO crops.

Europe exemplifies where US anti-GMO activists want to take America. Cultivating biotech plants is tightly restricted and thus effectively banned across the Atlantic (although they are widely imported for animal feed). A single variety of insect-resistant corn is only the such crop grown in Europe today. The EU could also ban the use of glyphosate as soon as 2022 and mandate that 25 percent of its farmland be converted to organic production by 2030. European regulators have already banned a class of pesticides known as neonicotinoids because they allegedly are responsible for a swath of bee deaths, though the evidence doesn’t support this conclusion.

If successful, activist efforts to push the US in Europe’s direction could leave American farmers with access to only subpar pest-control tools. The problem is compounded because consumers watch the courtroom drama play out on social media and demand access to “more sustainable” food options. Such developments prompt an obvious question: will the US follow in Europe’s footsteps?

New technologies on the horizon

The answer appears to be no, for two reasons. While anti-GMO groups have been successful in court recently, the American public is far less ‘precautionary’ in its view of chemicals, seeking a more evidence-based balance of risks and rewards. But there’s another twist to the story. The drumbeat of legal actions in recent years has begun spurring the development of a new generation of sustainable pest-control tools that will just be harder to ban.

Striking evidence of this trend surfaced in early July. “Conventional pesticide makers, including Syngenta and Bayer AG, have been under pressure in recent years over their products’ impact on the environment and biodiversity,” Bloomberg reported, “as more and more consumers grow more …. distrustful of pesticides used to produce their food.” In response, these biotech giants, alongside smaller startups and university research groups, have taken a variety of approaches to develop products that address sustainability concerns—everything from new seeds and pesticides to genetic technologies that reverse herbicide resistance in weeds and protect crops from pest attacks.

Gene-editing technology, which allows scientists to make specific changes to DNA, is one of the best tools researchers can use to tackle farm sustainability issues, and some early results are promising. With the help of tools like CRISPR, researchers are devising new combinations of herbicides and resistant crops that will give farmers options beyond the pest-control systems currently in the activist crosshairs. An herbicide-resistant canola variety developed through gene editing has been available in the US and Canada since 2016. And other crops, including corn, rice, wheat, soy and even watermelon, are also being engineered to withstand exposure to a variety of weedkillers.

Gene editing can also be used to immunize plants against attacks from insects and deadly pathogens. Significantly, these crops possess insect resistance that isn’t dependent on chemical spraying. That makes them more akin to transgenic (GMO) Bt crops already grown by farmers all over the world, such as eggplant in Bangladesh and cotton in India and the US. The resistance trait is bred into the plants themselves, so spraying is often cut to near zero. As they become available, these new plant varieties will rob anti-GMO activists of their current favorite line of attack: banning synthetic pesticides meant to be used in concert with biotech crops.

Natural biopesticides, typically developed from plants and microbes, are another important part of this effort to make farming more sustainable. GLP reported on the dramatic growth of biopesticides last summer, including a weedkiller known for now as MBI-014. The bacteria-based herbicide is effective against weeds that glyphosate and dicamba can’t control. In field trials completed last fall, the bioherbicide

… demonstrated control of a target weed approaching that of a current post-emergent chemical herbicide. At commercial rates across multiple trial locations that used uniform protocols, control of palmer amaranth was evaluated at three stages of growth, 7-to-10 days after MBI-015 was applied. Control ranged from the mid-70s to the high-80s percent ranges.

Gene-edited crops and biopesticides may prove to be especially important because they’re generally easier to get through the US regulatory system than transgenic plants and synthetic chemicals. In Europe, where gene-edited plants are regulated just like GMOs, biological pest controls may be the only novel technology capable of navigating the EU’s byzantine regulatory system.

But activists are not expected to suddenly drop their opposition, even though the environmental and health effects of these technologies are minimal. They will warn of “unintended consequences,” of course. They are wont to complain, for example, that developing new pesticides, natural or otherwise, and resistant crops fuels the so-called pesticide treadmill. “Patented GE seeds are designed for use with specific pesticides, leading to increased use of these chemicals,” warns Pesticide Action Network (PAN), another plaintiff in the lawsuits alongside CFS. “And widespread application of these pesticides leads to the emergence of herbicide-resistant ‘superweeds,’ which facilitates the need for more herbicides and GMO seeds resistant to them.” Yet many of these products are designed specifically to address the threat of pesticide resistance.

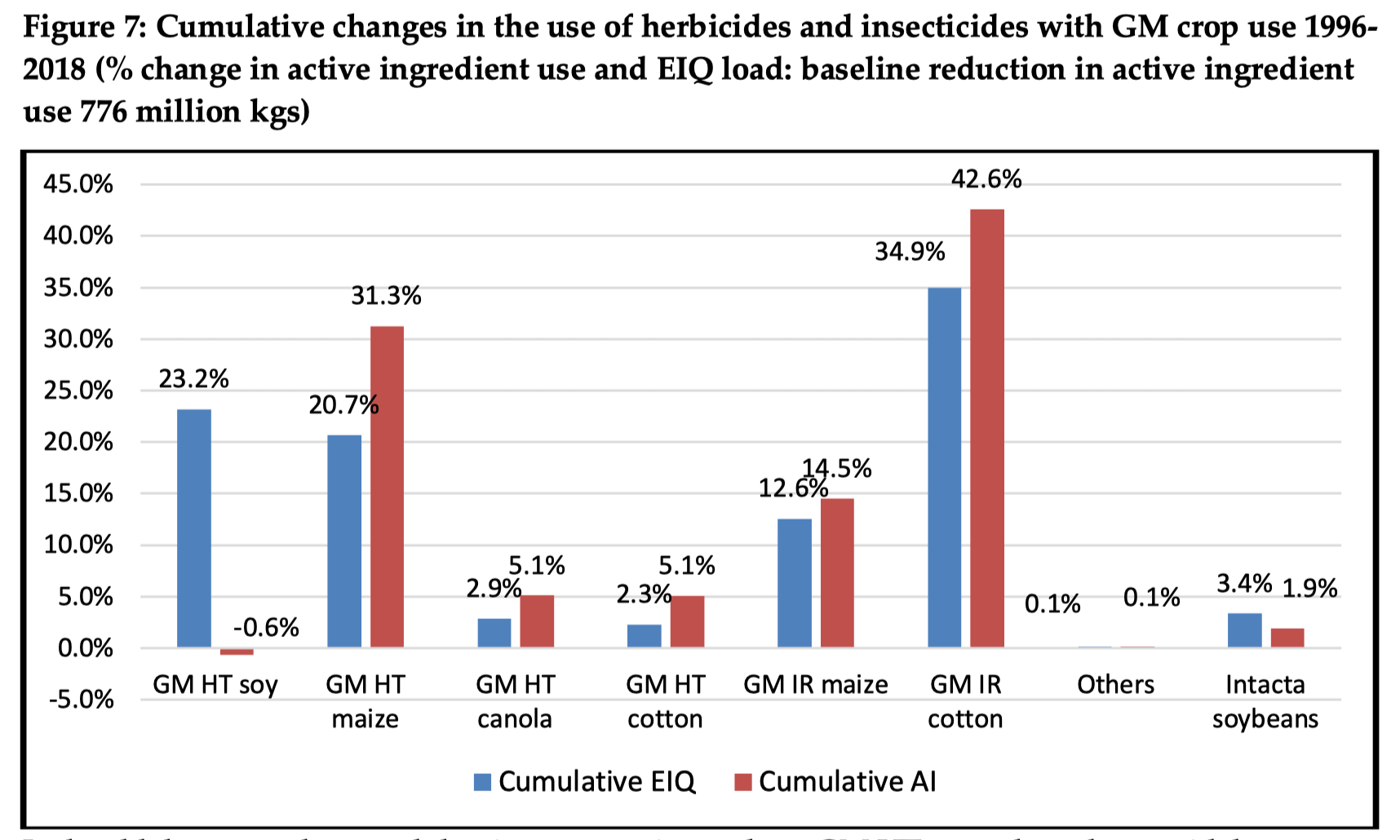

Farmers do rely on pesticides season after season, but utilizing a variety of weedkillers and insecticides alongside non-chemical strategies can help mitigate the risk of resistant weeds and bugs. That’s a key reason why the activist lawsuits to ban effective pesticides are counterproductive. The fewer chemistries farmers have access to, the more likely it is that resistance issues will arise. Moreover, two decades of research show that biotech crops have cut pesticide use by 776 million kilograms since their introduction in 1996. Despite these important qualifications often overlooked by activists, pesticide resistance remains a real concern for many farmers. Fortunately, biotechnology may yield a more direct solution in the coming years.

Reversing pesticide resistance

Reversing pesticide resistance

Beyond introducing more pesticides, it may be possible to re-sensitize weeds to chemical treatments they’ve become resistant to using modern genetic engineering techniques. Two approaches called virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) and Virus-mediated overexpression (VOX), for example, would allow scientists to turn off herbicide resistance in weeds. A team of scientists at UK-based Rothamsted Research demonstrated how these techniques work in an April 2020 study:

The team first inserted their gene of interest into a virus, and then infected the weed with it. During VIGS, the plant tries to defend itself and in the process shuts down production of all genes coming from the virus – including the weed’s own copies of the inserted gene – whereas during VOX, both the virus’ and the inserted gene’s copies manufacture proteins for the plant …. This made previously resistance plants susceptible

A similar technology, developed by Monsanto several years ago, involves treating herbicide-tolerant weeds with glyphosate and an RNA-based substance that shuts down their tolerance to the herbicide. Gene drives, which can be used to spread specific genetic alterations through targeted wild populations (of, say, weeds and crop pests), could also be used to eliminate pesticide resistance.

Center for Food Safety, Pesticide Action Network and their ideological allies won’t have a sudden change of heart on biotechnology. As they readily acknowledge, they’re on a campaign to promote organic farming, and that won’t end because we devise a long-term solution to herbicide resistance, especially given their recent success in court. What’s more interesting is that this extremist wing of the environmental movement has been gradually pushing itself into irrelevancy by attacking the technologies that make farming more sustainable; these recent biotech-fueled innovations are just the latest example of that process in action. As science writer Matt Ridley has pointed out:

Far from starving, the seven billion people who now inhabit the planet are far better fed than the four billion of 1980 …. Remarkably, this …. has happened without taking much new land under the plow and the cow …. Nor have these agricultural improvements on the whole brought new problems of pollution in their wake. Quite the reverse …. I was wrong to be pessimistic about the environment in 1980, and it would be wrong to give young people a counsel of despair today. Much has improved since then, and …. much improvement from here is not only possible, but likely.

Cameron J. English is the GLP’s managing editor. BIO. Follow him on Twitter @camjenglish