Greenhouse gas emissions are one of the environmental impacts of electricity generation. Measurement of life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions involves calculating the global warming potential of energy sources through life-cycle assessment. These are usually sources of only electrical energy but sometimes sources of heat are evaluated. The findings are presented in units of global warming potential per unit of electrical energy generated by that source. The scale uses the global warming potential unit, the carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e), and the unit of electrical energy, the kilowatt hour (kWh). The goal of such assessments is to cover the full life of the source, from material and fuel mining through construction to operation and waste management.

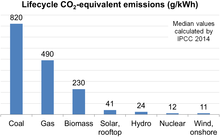

In 2014, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change harmonized the carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) findings of the major electricity generating sources in use worldwide. This was done by analyzing the findings of hundreds of individual scientific papers assessing each energy source. Coal is by far the worst emitter, followed by natural gas, with solar, wind and nuclear all low-carbon. Hydropower, biomass, geothermal and ocean power may generally be low-carbon, but poor design or other factors could result in higher emissions from individual power stations.

For all technologies, advances in efficiency, and therefore reductions in CO2e since the time of publication, have not been included. For example, the total life cycle emissions from wind power may have lessened since publication. Similarly, due to the time frame over which the studies were conducted, nuclear Generation II reactor's CO2e results are presented and not the global warming potential of Generation III reactors. Other limitations of the data include: a) missing life cycle phases, and, b) uncertainty as to where to define the cut-off point in the global warming potential of an energy source. The latter is important in assessing a combined electrical grid in the real world, rather than the established practice of simply assessing the energy source in isolation.

Global warming potential of selected electricity sources

| Technology | Min. | Median | Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently commercially available technologies | |||

| Coal – PC | 740 | 820 | 910 |

| Gas – combined cycle | 410 | 490 | 650 |

| Biomass – Dedicated | 130 | 230 | 420 |

| Solar PV – Utility scale | 18 | 48 | 180 |

| Solar PV – rooftop | 26 | 41 | 60 |

| Geothermal | 6.0 | 38 | 79 |

| Concentrated solar power | 8.8 | 27 | 63 |

| Hydropower | 1.0 | 24 | 2200 |

| Wind Offshore | 8.0 | 12 | 35 |

| Nuclear | 3.7 | 12 | 110 |

| Wind Onshore | 7.0 | 11 | 56 |

| Pre‐commercial technologies | |||

| Ocean (Tidal and wave) | 5.6 | 17 | 28 |

| Technology | gCO2eq/kWh | |

|---|---|---|

| Hard coal | PC, without CCS | 1000 |

| IGCC, without CCS | 850 | |

| SC, without CCS | 950 | |

| PC, with CCS | 370 | |

| IGCC, with CCS | 280 | |

| SC, with CCS | 330 | |

| Natural gas | NGCC, without CCS | 430 |

| NGCC, with CCS | 130 | |

| Hydro | 660 MW | 150 |

| 360 MW | 11 | |

| Nuclear | average | 5.1 |

| CSP | tower | 22 |

| trough | 42 | |

| PV | poly-Si, ground-mounted | 37 |

| poly-Si, roof-mounted | 37 | |

| CdTe, ground-mounted | 12 | |

| CdTe, roof-mounted | 15 | |

| CIGS, ground-mounted | 11 | |

| CIGS, roof-mounted | 14 | |

| Wind | onshore | 12 |

| offshore, concrete foundation | 14 | |

| offshore, steel foundation | 13 | |

List of acronyms:

- PC — pulverized coal

- CCS — carbon capture and storage

- IGCC — integrated gasification combined cycle

- SC — supercritical

- NGCC — natural gas combined cycle

- CSP — concentrated solar power

- PV — photovoltaic power

Bioenergy with carbon capture and storage

As of 2020 whether bioenergy with carbon capture and storage can be carbon neutral or carbon negative is being researched and is controversial.

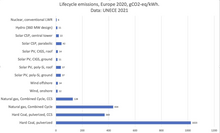

Studies after the 2014 IPCC report

Individual studies show a wide range of estimates for fuel sources arising from the different methodologies used. Those on the low end tend to leave parts of the life cycle out of their analysis, while those on the high end often make unrealistic assumptions about the amount of energy used in some parts of the life cycle.

Since the 2014 IPCC study some geothermal has been found to emit CO2 such as some geothermal power in Italy: further research is ongoing in the 2020s.

Ocean energy technologies (tidal and wave) are relatively new, and few studies have been conducted on them. A major issue of the available studies is that they seem to underestimate the impacts of maintenance, which could be significant. An assessment of around 180 ocean technologies found that the GWP of ocean technologies varies between 15 and 105 gCO2eq/kWh, with an average of 53 gCO2eq/kWh. In a tentative preliminary study, published in 2020, the environmental impact of subsea tidal kite technologies the GWP varied between 15 and 37, with a median value of 23.8 gCO2eq/kWh), which is slightly higher than that reported in the 2014 IPCC GWP study mentioned earlier (5.6 to 28, with a mean value of 17 gCO2eq/kWh).

In 2021 UNECE published a lifecycle analysis of environmental impact of electricity generation technologies, accounting for the following impacts: resource use (minerals, metals); land use; resource use (fossils); water use; particulate matter; photochemical ozone formation; ozone depletion; human toxicity (non-cancer); ionising radiation; human toxicity (cancer); eutrophication (terrestrial, marine, freshwater); ecotoxicity (freshwater); acidification; climate change, with the latter summarized in the table above.

In June 2022, Électricité de France publishes a detailed Life-cycle assessment study, following the norm ISO 14040, showing the 2019 French nuclear infrastructure produces less than 4 gCO2eq/kWh.

Cutoff points of calculations and estimates of how long plants last

Because most emissions from wind, solar and nuclear are not during operation, if they are operated for longer and generate more electricity over their lifetime then emissions per unit energy will be less. Therefore, their lifetimes are relevant.

Wind farms are estimated to last 30 years: after that the carbon emissions from repowering would need to be taken into account. Solar panels from the 2010s may have a similar lifetime: however how long 2020s solar panels (such as perovskite) will last is not yet known. Some nuclear plants can be used for 80 years, but others may have to be retired earlier for safety reasons. As of 2020 more than half the world's nuclear plants are expected to request license extensions, and there have been calls for these extensions to be better scrutinised under the Convention on Environmental Impact Assessment in a Transboundary Context.

Some coal-fired power stations may operate for 50 years but others may be shut down after 20 years, or less. According to one 2019 study considering the time value of GHG emissions with techno-economic assessment considerably increases the life cycle emissions from carbon intensive fuels such as coal.

Lifecycle emissions from heating

For residential heating in almost all countries emissions from natural gas furnaces are more than from heat pumps. But in some countries, such as the UK, there is an ongoing debate in the 2020s about whether it is better to replace the natural gas used in residential central heating with hydrogen, or whether to use heat pumps or in some cases more district heating.

Fossil gas bridge fuel controversy

As of 2020 whether natural gas should be used as a "bridge" from coal and oil to low carbon energy, is being debated for coal-reliant economies, such as India, China and Germany. Germany, as part of its Energiewende transformation, declares preservation of coal-based power until 2038 but immediate shutdown of nuclear power plants, which further increased its dependency on fossil gas.

Missing life cycle phases

Although the life cycle assessments of each energy source should attempt to cover the full life cycle of the source from cradle-to-grave, they are generally limited to the construction and operation phase. The most rigorously studied phases are those of material and fuel mining, construction, operation, and waste management. However, missing life cycle phases exist for a number of energy sources. At times, assessments variably and sometimes inconsistently include the global warming potential that results from decommissioning the energy supplying facility, once it has reached its designed life-span. This includes the global warming potential of the process to return the power-supply site to greenfield status. For example, the process of hydroelectric dam removal is usually excluded as it is a rare practice with little practical data available. Dam removal however is becoming increasingly common as dams age. Larger dams, such as the Hoover Dam and the Three Gorges Dam, are intended to last "forever" with the aid of maintenance, a period that is not quantified. Therefore, decommissioning estimates are generally omitted for some energy sources, while other energy sources include a decommissioning phase in their assessments.

Along with the other prominent values of the paper, the median value presented of 12 g CO2-eq/kWhe for nuclear fission, found in the 2012 Yale University nuclear power review, a paper which also serves as the origin of the 2014 IPCC's nuclear value, does however include the contribution of facility decommissioning with an "Added facility decommissioning" global warming potential in the full nuclear life cycle assessment.

Thermal power plants, even if low carbon power biomass, nuclear or geothermal energy stations, directly add heat energy to the earth's global energy balance. As for wind turbines, they may change both horizontal and vertical atmospheric circulation. But, although both these may slightly change the local temperature, any difference they might make to the global temperature is undetectable against the far larger temperature change caused by greenhouse gases.