Research indicates that living in areas of high pollution has serious long term health effects. Living in these areas during childhood and adolescence can lead to diminished mental capacity and an increased risk of brain damage. People of all ages who live in high pollution areas for extended periods place themselves at increased risk of various neurological disorders. Both air pollution and heavy metal pollution have been implicated as having negative effects on central nervous system (CNS) functionality. The ability of pollutants to affect the neurophysiology of individuals after the structure of the CNS has become mostly stabilized is an example of negative neuroplasticity.

Air pollution

Air pollution may increase the risk of developmental disorders (e.g., autism), neurodegenerative disorders, mental disorders, and suicide. It is associated with neurological conditions including stroke, multiple sclerosis, dementia, Parkinson disease, Alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia and headaches.

Effects in adolescents

A 2008 study compared children and dogs raised in Mexico City (a location known for high pollution levels) with children and dogs raised in Polotitlán, Mexico (a city whose pollution levels meet the current US National Ambient Air Quality Standards). Children raised in areas of higher pollution were found to score lower in intelligence (i.e., on IQ tests), and showed signs of lesions in MRI scanning of the brain. In contrast, children from the low pollution area scored as expected on IQ tests and showed no significant sign of the risk of brain lesions. Concerning traffic-related air pollution, children of mothers exposed to higher levels during the first trimester of pregnancy were at increased risk of allergic sensitization at one year age.

Effects in adults

Effects of physical activity and air pollution on neuroplasticity may counteract. Physical activity is known for its benefits to the cardiovascular system, brain plasticity processes, cognition and mental health. The neurotrophine, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is thought to play a key role in exercise-induced cognitive improvements. Brief bouts of physical activity may increase serum levels of BDNF, but this increase may be offset by increased exposure to traffic-related air pollution. Over longer periods of physical exercise, the cognitive improvements which were demonstrated in rural joggers were found to be absent in urban joggers who were partaking in the same 12-week start-2-run training programme. During exercise, traffic-related air pollution may reduce the beneficial effects of that exercise.

Cognitive performance

Analyzing 2017 and 2018 data from Lost in Migration, a phone game that test players' ability to keep their focus, researchers found effects of wildfire smoke and pollution particulates on brain performance.

"We found evidence suggesting that fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can reduce attention in adults within just hours of exposure. This is a very quick turnaround between exposure and decreased cognitive performance and may have implications when thinking about time-sensitive public health communication during extreme air pollution events like wildfires," Cleland, a predoctoral ORISE fellow at EPA, explained. It was also found that prolonged exposure to particulate pollution shortens attention spans in younger populations specifically. In both the long-term and short-term analyses, exposure to harmful particulates caused lower game scores.

Sources of pollution

Airborne particulate matter is a Group 1 carcinogen. Particulates are the most harmful form (other than ultra-fines) of air pollution as they can penetrate deep into the lungs and brain from blood streams, causing health problems such as heart disease, lung disease, and premature death. There is no safe level of particulates. Ultrafine particles are both manufactured and naturally occurring. Hot volcanic lava, ocean spray, and smoke are common natural UFPs sources. UFPs can be intentionally fabricated as fine particles to serve a vast range of applications in both medicine and technology. Other UFPs are byproducts, like emissions, from specific processes, combustion reactions, or equipment such as printer toner and automobile exhaust. Anthropogenic sources of UFPs include combustion of gas, coal or hydrocarbons, biomass burning (i.e. agricultural burning, forest fires and waste disposal), vehicular traffic and industrial emissions, tire wear and tear from car brakes, air traffic, seaport, maritime transportation, construction, demolition, restoration and concrete processing, domestic wood stoves, outdoor burning, kitchen, and cigarette smoke.

While hand-held power tools are very helpful (e.g., in renovation and construction), they also produce large amounts of vibrations and particulates (particulate matter), including ultrafine particles, from both fuel combustion and the mechanical tasks. Not only power tools, hand tools also generate UFPs.

Many construction tasks create dust. High dust levels are caused by one of more the following:

- equipment – using high energy tools, such as cut-off saws, grinders, wall chasers and grit blasters produce a lot of dust in a very short time

- work method – dry sweeping can make a lot of dust when compared to vacuuming or wet brushing

- work area – the more enclosed a space, the more the dust will build up

- time – the longer you work the more dust there will be

Examples of high dust level tasks include:

- using power tools to cut, grind, drill or prepare a surface

- sanding taped plaster board joints

- dry sweeping

Currently there seems to be no or little regulations on the size and amount of dust emitted by power tools. Some industry standards do exist, though it appears that they are not widely known or used globally. Knowing that dust is generated throughout the construction process and can cause serious health hazards, manufacturers are now marketing power tools that are equipped with dust collection system (e.g. HEPA vacuum cleaner) or integrated water delivery system which extract the dust after emission. However, the use of such products is still not common in most places. As Q1 2024 petrol powered tools are banned in California.

- Construction dust generated by power tools and heavy equipments

Pollutants

Dioxin poisoning

Organohalogen compounds, such as dioxins, are commonly found in pesticides or created as by-products of pesticide manufacture or degradation. These compounds can have a significant impact on the neurobiology of exposed organisms. Some observed effects of exposure to dioxins are altered astroglial intracellular calcium ion (Ca2+), decreased glutathione levels, modified neurotransmitter function in the CNS, and loss of pH maintenance. A study of 350 chemical plant employees exposed to a dioxin precursor for herbicide synthesis between 1965 and 1968 showed that 80 of the employees displayed signs of dioxin poisoning. The study suggested that the effects of dioxins were not limited to initial toxicity. Dioxins, through neuroplastic effects, may cause long-term damage that may not manifest itself for years or even decades.

Metal exposure

Heavy metal exposure can result in an increased risk of various neurological diseases. The two most neurotoxic heavy metals are mercury and lead. The impact of the two heavy metals is highly dependent upon the individual due to genetic variations. Mercury and lead are particularly neurotoxic for many reasons: they easily cross cell membranes, have oxidative effects on cells, react with sulfur in the body (leading to disturbances in the many functions that rely upon sulfhydryl groups), and reduce glutathione levels inside cells. Methylmercury, in particular, has an extremely high affinity for sulfhydryl groups. Organomercury is a particularly damaging form of mercury because of its high absorbability Lead also mimics calcium, a very important mineral in the CNS, and this mimicry leads to many adverse effects. Mercury's neuroplastic mechanisms work by affecting protein production. Elevated mercury levels increase glutathione levels by affecting gene expression, and this in turn affects two proteins (MT1 and MT2) that are contained in astrocytes and neurons.

Lead's ability to imitate calcium allows it to cross the blood–brain barrier. Lead also upregulates glutathione. Blood lead concentrations ≥ 5·0 μg/dL could result in children scoring 3–5 points lower in intelligence tests than those with the concentrations < 5·0 μg/dL . Higher blood lead concentrations are also associated with serious cognitive function losses. "Lead-related IQ losses are associated with increased rates of school failure, behavioural disorders, diminished economic productivity, and global economic losses of almost $1 trillion annually."

Conditions and disorders

Developmental disorders

Autism

Heavy metal exposure, when combined with certain genetic predispositions, can place individuals at increased risk for developing autism. Many examples of CNS pathophysiology, such as oxidative stress, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction, could be by-products of environmental stressors such as pollution, as found in a 2010 study. There have been reports of autism outbreaks occurring in specific locations.

Early-life exposure to air pollution may be a risk factor for autism. Children of mothers living near a freeway, and traffic-related pollution, during the third trimester of pregnancy were twice as likely to develop ASD. A distance of 1,014 feet, or a little less than 3.5 football fields, was considered near a freeway. Children with a mutation in a gene called MET, combined with high levels of exposure to air pollution, may have increased risk.

Prenatal and early childhood exposure to heavy metals, like mercury, lead, or arsenic; altered levels of essential metals like zinc or manganese; pesticides; and other contaminants cause concern. A study of twins used baby teeth to determine and compare levels of lead, manganese, and zinc in children with autism to their twin without the condition. Autistic children were low on manganese and zinc, metals essential to life, but had higher levels of lead, a harmful metal during specific developmental time periods studied. Altered zinc-copper cycles, which regulate metal metabolism in the body, are disrupted in ASD cases.

Maternal exposure to insecticides during early pregnancy was associated with higher risk of autism in their children. Contaminants such as Bisphenol A, phthalates, flame retardants, and polychlorinated biphenyls are also being studied.

Neurodegenerative disorders

Accelerated neural aging

Neuroinflammation is associated with increased rates of neurodegeneration. Inflammation tends to increase naturally with age. By facilitating inflammation, pollutants such as air particulates and heavy metals cause the CNS to age more quickly. Many late-onset diseases are caused by neurodegeneration. Multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and Alzheimer's disease are all believed to be exacerbated by inflammatory processes, resulting in individuals displaying signs of these diseases at an earlier age than is typically expected.

Multiple sclerosis occurs when chronic inflammation leads to the compromise of oligodendrocytes, which in turn leads to the destruction of the myelin sheath. Then axons begin exhibiting signs of damage, which in turn leads to neuron death. Multiple sclerosis has been correlated to living in areas with high particulate matter levels in the air.

According to Lancet (2021), exposure to "environmental pollution with toxins, such as pesticides (eg, paraquat) or chemicals (eg, trichloroethylene), known to be harmful to Parkinson's disease-related neurons and brain circuits," is associated with Parkinson's disease. Multi-decade studies have identified an increased likelihood of Parkinson's in association with agricultural work, pesticide exposure, and rural habitation. Chlorinated solvents, used in commercial and industrial application like dry cleaning and degreasing, are associated with increased PD risk, particularly trichloroethylene. Other chemical risk factors include manganese, suspended particles from traffic fumes, and exposure to other heavy metals such as mercury and lead.

In the case of Alzheimer's disease, inflammatory processes lead to neuron death by inhibiting growth at axons and activating astrocytes that produce proteoglycans. This product can only be deposited in the hippocampus and cortex, indicating that this may be the reason these two areas show the highest levels of degeneration in Alzheimer's disease. Tiny particles (e.g., engineered nanoparticles and combustion nanoparticle emissions, also called nanomaterials, including those containing manganese) can bypass the blood-brain barrier (the body's filtering system) and enter the brain as they are breathed in.

A study on the young adult citizens in Metropolitan Mexico City (MMC) found association between air pollution exposure and olfactory dysfunction and pathology in the olfactory bulb. The young adults demonstrated olfactory bulb endothelial hyperplasia, neuronal accumulation of particles, and immunoreactivity to Aβ and/or α-synuclein in neurons, glial cells and/or blood vessels. There were ultrafine particles deposited in their endothelial cytoplasm and basement membranes of the olfactory bulb.

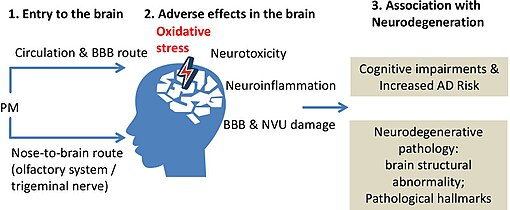

Studies consistently suggested a strong link between chronic exposure to PM, especially PM2.5 and UFPM, with the onset of dementia and AD, as well as neurodegenerative-like pathology and cognitive deficits. The central role of oxidative stress was highlighted in the neuronal injury caused by PM. Neuroinflammation could further damage the neurons and other cells such as the endothelial cells in the neurovascular unit (NVU). The neurovascular unit consists of neurons, astrocytes, vasculature (endothelial and vascular mural cells), the vasomotor apparatus (smooth muscle cells and pericytes), and microglia. Targeting the HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB pathways or oxidative stress by pharmacological inhibitors or genetic knockdown has demonstrated potential as an therapeutic intervention.

Effects of PM on metabolism should be further studied according to the results in the neurometabolomics analysis as studies not only showed the implication of disturbed glutathione metabolism in the pathogenesis of PM-induced neuronal injury but also demonstrated that PM may affect the fatty acid and energy metabolism in the neurons. Injury in the NVU after exposure to PM would also impair energy metabolism in the affected brain regions. Therefore, the disturbed metabolic homeostasis may also play a crucial pathogenic role in the development of PM-induced neuropathology. Restoring these metabolic disturbances may enhance the resistance of neurons against the stress caused by exposure to PM.

Cognitive decline and dementia

Exposure to air pollution was positively associated with an increased risk of stroke hospital admission (PM2.5, PM10, SO2, NO2, CO, and O3), incidence (PM2.5, SO2, and NO2), and mortality (PM2.5, PM10, SO2, and NO2). There is a "well-recognized link between PM2.5 and vascular injury and the role of vascular injury in dementia". Air pollution in the cerebrovascular system may result in “stroke, vascular dementia, or other types of dementia". The risk of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia, may be increased by long-term exposure to PM2.5.

Interest in the possible effects of air pollutants on the brain began in about 2002 when Calderon-Garciduenas and colleagues reported that dogs exposed to air pollution in Mexico City showed neuropathological changes of the type associated with Alzheimer's disease. This work was an extension of studies undertaken in the 1990s on the effects of Mexico City air pollution on the olfactory epithelium of humans and dogs. Later, interest in possible effects on the brain has been strengthened by epidemiological studies, which suggest that exposure to air pollutants is associated with a decline of cognitive function and the development of dementia.

Magnetite nanoparticles have been found in the brain with a morphology that suggests an exogenous origin. Similar ferrous nanoparticles were found in air collected at traffic roadsides in the UK. These nanoparticles may be able to reach the brain via the olfactory nerves and olfactory bulb, or via the circumventricular organs where the blood-brain barrier is more permeable. In addition, the blood-brain barrier could be made less impermeable by systemic inflammation for which exposure to air pollutants is a known risk factor. The blood-brain barrier is also more permeable in the very young and old, making these two life stages opportunities for the entry of nanoparticles into the brain, and potential elicitation of neurological damage.

In addition to the possible direct effects from nanoparticles reaching the brain, there are indirect mechanisms by which pollutants could potentially lead to brain injury. These include damage to the vasculature, leading to cerebral ischaemia or extravasation of neurotoxic proteins such as fibrinogen. Brain injury could also be secondary to systemic inflammatory responses to air pollution.

Calderon-Garciduenas et al. reviewed their work in children and youngsters in Mexico City and reported neuropathological changes in children and young adults similar to those in Alzheimer's disease. There was increased neuro-inflammation and vascular damage: upregulated mRNA cyclooxygenase-2, interleukin-1β and CD14, and clusters of mononuclear cells around blood vessels and activated microglia in the frontal and temporal cortex, subiculum and brain stem. They also found deposits of amyloid-β42, α-synuclein, hyperphosphorylated tau, and evidence of oxidative stress, neuronal damage and death. Children in Mexico City (with high levels of air pollution) also had low serum BDNF concentrations.

Studies of white matter volume found associations between exposure to air pollution and reduced white matter volume. Evidence suggests that long-term exposure to air pollutants is associated with cognitive decline and with the risk of development of dementia. There is epidemiological evidence suggestive of a causal association between exposure to a range of air pollutants and a number of effects on the nervous system including the acceleration of cognitive decline and the induction of dementia.

Dementia is an umbrella term for a range of conditions that affect how the brain works, reducing the ability to remember, think and reason. It mainly affects older people and gets worse over time. Health and lifestyle factors such as high blood pressure and smoking are known to increase the risk of developing dementia.

The Committee on the Medical Effects of Air Pollutants (COMEAP) in UK have reviewed nearly 70 studies in human populations (epidemiological studies) and think it is likely that air pollution can contribute to a decline in mental ability and dementia in older people. It is known that air pollution, particularly small particle pollution, can affect the heart and the circulatory system, including circulation to the brain. These effects are linked to vascular dementia (a form of dementia), which is caused by damage to the blood vessels in the brain. Therefore, it is likely that air pollution contributes to mental decline and dementia caused by effects on the blood vessels. Air pollution might also stimulate the immune cells in the brain, which can then damage nerve cells.

In 2022, COMEAP has concluded that the evidence is suggestive of an association between ambient air pollutants and an acceleration of the decline in cognitive function often associated with ageing, and with the risk of developing dementia. There are a number of plausible biological mechanisms by which air pollutants could cause effects on the brain leading to accelerated cognitive decline and dementia. Some of these have been demonstrated in experimental studies. There is a strong case for the effects of air pollutants on the cardiovascular system having a secondary effect on the brain. COMEAP has already concluded that long-term exposure to air pollutants damages the cardiovascular system (COMEAP 2006, 2018). It is likely that such effects have an effect on the blood supply to the brain. That such an effect might well lead to damage to the brain seems likely. Therefore it is regarded that the association between exposure to air pollutants and effects on cognitive decline and dementia as likely to be causal with respect to this mechanism.

A number of mechanisms have been suggested by which air pollutants could have direct effects on the brain. These include the translocation of small particles from the lung to the blood stream and thence to the brain. The evidence suggests that a small proportion of very small particles that are inhaled can enter the brain, both from the blood and via the olfactory nerves leading from the nasal passages to the olfactory bulbs. What is much less clear is whether exposure to ambient concentrations of particulate material results in sufficient translocation to produce damage to the brain. Study of the literature has suggested that particles which enter the brain are cleared from the brain only slowly, if at all. This is clearly a point in favour of the suggestion that particulate material which does enter the brain might produce detrimental effects. Animal and in vitro studies of ultrafine particulate material, diesel engine exhaust or ozone have all shown effects on the brain or brain cells. The mechanisms involved include the generation and release of free radicals within the brain and the induction of an inflammatory response; these 2 mechanisms seem likely to be linked. A number of common pollutants may affect brain function.

COMEAP concluded that:

- The epidemiological evidence is suggestive of an association between exposure to ambient air pollutants and both the risk of developing dementia and acceleration of cognitive decline. The epidemiological literature is inconsistent as to which pollutant is most associated with these effects.

- There is evidence that air pollution, particularly particulate air pollution, increases the risk of cardiovascular, including cerebrovascular, disease. These diseases are known to have adverse effects on cognitive function. There is likely to be a causal association between particulate air pollution and effects on cognitive function in older people.

- As of 2022, direct quantification of cognitive decline or dementia associated with air pollution would be subject to unknown uncertainty.

- It may be possible to develop an indirect method of quantification of cognitive effects secondary to the effects of particulate pollution on cardiovascular disease.

Mental disorders

Schizophrenia

Exposure to air pollution may be associated with elevated risk of schizophrenia.

Others

Epilepsy

Multiple air pollutants are probably associated with the risk of epilepsy, e.g., carbon monoxide, ozone, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, large particulate matter, and fine particulate matter. It was hypothesized that air pollutants increase epilepsy risk by increasing inflammatory mediators, and by providing a source of oxidative stress, eventually altering the blood–brain barrier's function and cause brain inflammation. Brain inflammation is known to be a risk factor for epilepsy; thus, the sequence of events provides a plausible mechanism by which pollution may increase epilepsy risk in individuals who are genetically vulnerable to the disease.

Economics

Dementia

Dementia is a pressing public health challenge. Its prevalence is strongly age-related: doubling every 5–6 years over the age of 65 years. The number of people living with dementia worldwide is estimated at 50 million and expected to reach 152 million by 2050. Its current economic cost worldwide is US$818 billion/year (as of 2015) and it will rise in proportion to the numbers affected (WHO, 2019).

Mitigations

For point-source pollution: Do not produce the pollutants. If produced, remove at source as soon as possible. If not removed at source, use barriers. If barriers do not work well or not installed properly (i.e., pollutants escaped), neighbours need filtration, sealing, and/or proper ventilation / pollutant dilution, etc. for their premises. Large scale air cleaning system may also help as a passive measure. Clean-up programmes may be needed to prevent further secondary contamination or pollution.

At individual level, exposure reduction of air pollutants maybe achieved by better choice of places that one stays, prevention of cross-contamination or secondary contamination (between persons and/or their personal belongings/environment), better personal hygiene, use of face masks and air purifiers, etc.

Education

Priority areas in “Education and Awareness included: (8) making this unrecognised public health issue known; (9) developing educational products; (10) attaching air pollution and brain health to existing strategies and campaigns; and (11) providing publicly available monitoring, assessment and screening tools...”

Diet

Autism

NIEHS-funded studies have found taking prenatal vitamins may help lower autism risk. Taking vitamins and supplements might provide protective effects for those exposed to certain environmental contaminants during pregnancy. Women were less likely to have a child with autism if they took a daily prenatal vitamin during the three months before and first month of pregnancy, compared to women not taking vitamins. This finding was more evident in women and children with genetic variants that made them more susceptible to developing autism.

Folic acid is a source of the protective effects of prenatal vitamins. Women who took the daily recommended dosage during the first month of pregnancy had a reduced risk of having a child with autism. Folic acid intake during early pregnancy may reduce the risk of having a child with autism for those women with high exposure to air pollution, and pesticides.

Pregnant mothers who used multivitamins, with or without additional iron or folic acid, were less likely to have a child with autism and intellectual disability. Maternal prenatal vitamin intake during the first month of pregnancy may also reduce ASD recurrence in siblings of children with ASD in high-risk families.