Many countries regulate the work week by law, such as stipulating minimum daily rest periods, annual holidays, and a maximum number of working hours

per week. Working time may vary from person to person, often depending

on economic conditions, location, culture, lifestyle choice, and the

profitability of the individual's livelihood. For example, someone who

is supporting children and paying a large mortgage might need to work

more hours to meet basic costs of living than someone of the same earning power

with lower housing costs. In developed countries like the United

Kingdom, some workers are part-time because they are unable to find

full-time work, but many choose reduced work hours to care for children

or other family; some choose it simply to increase leisure time.

Standard working hours (or normal working hours) refers to the legislation to limit the working hours per day, per week, per month or per year. If an employee needs to work overtime, the employer will need to pay overtime payments to employees as required in the law. Generally speaking, standard working hours of countries worldwide are around 40 to 44 hours per week (but not everywhere: from 35 hours per week in France to up to 112 hours per week in North Korean labor camps) and the additional overtime payments are around 25% to 50% above the normal hourly payments.[citation needed] Maximum working hours refers to the maximum working hours of an employee. The employee cannot work more than the level specified in the maximum working hours law.

Standard working hours (or normal working hours) refers to the legislation to limit the working hours per day, per week, per month or per year. If an employee needs to work overtime, the employer will need to pay overtime payments to employees as required in the law. Generally speaking, standard working hours of countries worldwide are around 40 to 44 hours per week (but not everywhere: from 35 hours per week in France to up to 112 hours per week in North Korean labor camps) and the additional overtime payments are around 25% to 50% above the normal hourly payments.[citation needed] Maximum working hours refers to the maximum working hours of an employee. The employee cannot work more than the level specified in the maximum working hours law.

Hunter-gatherer

Since the 1960s, the consensus among anthropologists, historians, and sociologists has been that early hunter-gatherer societies enjoyed more leisure time than is permitted by capitalist and agrarian societies; for instance, one camp of !Kung Bushmen was estimated to work two-and-a-half days per week, at around 6 hours a day. Aggregated comparisons show that on average the working day was less than five hours.

Subsequent studies in the 1970s examined the Machiguenga of the Upper Amazon and the Kayapo

of northern Brazil. These studies expanded the definition of work

beyond purely hunting-gathering activities, but the overall average

across the hunter-gatherer societies he studied was still below 4.86

hours, while the maximum was below 8 hours.

Popular perception is still aligned with the old academic consensus

that hunter-gatherers worked far in excess of modern humans' forty-hour

week.

History

The industrial revolution

made it possible for a larger segment of the population to work

year-round, because this labor was not tied to the season and artificial

lighting made it possible to work longer each day. Peasants and farm laborers moved from rural areas to work in urban factories, and working time during the year increased significantly. Before collective bargaining and worker protection laws,

there was a financial incentive for a company to maximize the return on

expensive machinery by having long hours. Records indicate that work

schedules as long as twelve to sixteen hours per day, six to seven days

per week were practiced in some industrial sites.

1906 – strike for the 8 working hours per day in France

Over the 20th century, work hours shortened by almost half, mostly

due to rising wages brought about by renewed economic growth, with a

supporting role from trade unions, collective bargaining, and progressive legislation. The workweek, in most of the industrialized world, dropped steadily, to about 40 hours after World War II. The limitation of working hours is also proclaimed by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, and European Social Charter. The decline continued at a faster pace in Europe: for example, France adopted a 35-hour workweek

in 2000. In 1995, China adopted a 40-hour week, eliminating half-day

work on Saturdays (though this is not widely practiced). Working hours

in industrializing economies like South Korea, though still much higher than the leading industrial countries, are also declining steadily.

Technology has also continued to improve worker productivity, permitting standards of living to rise as hours decline.

In developed economies, as the time needed to manufacture goods has

declined, more working hours have become available to provide services, resulting in a shift of much of the workforce between sectors.

Economic growth in monetary terms tends to be concentrated in

health care, education, government, criminal justice, corrections, and

other activities that are regarded as necessary for society rather than

those that contribute directly to the production of material goods.

In the mid-2000s, the Netherlands was the first country in the industrialized world where the overall average working week dropped to less than 30 hours.

Gradual decrease in working hours

Most countries in the developed world have seen average hours worked decrease significantly. For example, in the U.S in the late 19th century it was estimated that the average work week was over 60 hours per week. Today the average hours worked in the U.S. is around 33,

with the average man employed full-time for 8.4 hours per work day,

and the average woman employed full-time for 7.9 hours per work day.

The front runners for lowest average weekly work hours are the Netherlands with 27 hours, and France with 30 hours. In a 2011 report of 26 OECD countries, Germany had the lowest average working hours per week at 25.6 hours.

The New Economics Foundation

has recommended moving to a 21-hour standard work week to address

problems with unemployment, high carbon emissions, low well-being,

entrenched inequalities, overworking, family care, and the general lack

of free time. Actual work week lengths have been falling in the developed world.

Factors that have contributed to lowering average work hours and increasing standard of living have been:

- Technological advances in efficiency such as mechanization, robotics and information technology.

- The increase of women equally participating in making income as opposed to previously being commonly bound to homemaking and childrearing exclusively.

- Dropping fertility rates leading to fewer hours needed to be worked to support children.

Recent articles supporting a four-day week

have argued that reduced work hours would increase consumption and

invigorate the economy. However, other articles state that consumption

would decrease.

Other arguments for the four-day week include improvements to workers'

level of education (due to having extra time to take classes and

courses) and improvements to workers' health (less work-related stress

and extra time for exercise). Reduced hours also save money on day care costs and transportation, which in turn helps the environment with less carbon-related emissions. These benefits increase workforce productivity on a per-hour basis.

Workweek structure

The structure of the work week varies considerably for different

professions and cultures. Among salaried workers in the western world,

the work week often consists of Monday to Friday or Saturday with the weekend set aside as a time of personal work and leisure. Sunday is set aside in the western world because it is the Christian sabbath.

The traditional American business hours are 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., Monday to Friday, representing a workweek of five eight-hour days comprising 40 hours in total. These are the origin of the phrase 9-to-5, used to describe a conventional and possibly tedious job. Negatively used, it connotes a tedious or unremarkable occupation. The phrase also indicates that a person is an employee, usually in a large company, rather than an entrepreneur or self-employed. More neutrally, it connotes a job with stable hours and low career risk, but still a position of subordinate employment. The actual time at work often varies between 35 and 48 hours in practice due to the inclusion, or lack of inclusion, of breaks. In many traditional white collar positions, employees were required to be in the office

during these hours to take orders from the bosses, hence the

relationship between this phrase and subordination. Workplace hours have

become more flexible, but the phrase is still commonly used.

Several countries have adopted a workweek from Monday morning until Friday noon, either due to religious rules (observation of shabbat in Israel

whose workweek is Sunday to Friday afternoon) or the growing

predominance of a 35–37.5 hour workweek in continental Europe. Several

of the Muslim countries have a standard Sunday through Thursday or

Saturday through Wednesday workweek leaving Friday for religious

observance, and providing breaks for the daily prayer times.

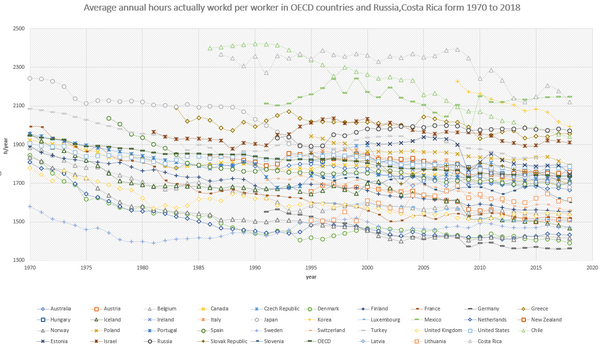

Average annual hours actually worked per worker

OECD ranking

Trends over time

Average annual hours actually worked per worker in OECD countries from 1970 to 2011

Differences among countries and regions

European countries

In most European Union countries, working time is gradually decreasing. The European Union's working time directive imposes a 48-hour maximum working week that applies to every member state except the United Kingdom and Malta

(which have an opt-out, meaning that UK-based employees may work longer

than 48 hours if they wish, but they cannot be forced to do so). France has enacted a 35-hour workweek by law, and similar results have been produced in other countries through collective bargaining. A major reason for the lower annual hours worked in Europe is a relatively high amount of paid annual leave.

Fixed employment comes with four to six weeks of holiday as standard.

In the UK, for example, full-time employees are entitled to 28 days of

paid leave a year.

France

France

experimented in 2000 a sharp cut of legal or statutory working time of

the employees in the private and public sector from 39 hours a week to

35 hours a week, with the stated goal to fight against rampant

unemployment at that time. The Law 2000-37 on working time reduction is

also referred to as the Aubry Law, according to the name of the Labor

Minister at that time.

Employees can (and do) work more than 35 hours a week, yet in this case

firms must pay them overtime bonuses. If the bonus is determined through

collective negotiations, it cannot be lower than 10%. If no agreement

on working time is signed, the legal bonus must be of 25% for the first 8

hours, than goes up to 50% for the rest.

Including overtime, the maximum working time cannot exceed 48 hours per

week, and should not exceed 44 hours per week over 12 weeks in a row.

In France the labor law also regulates the minimum working hours: part

time jobs should not allow for less than 24 hours per week without a

branch collective agreement. These agreements can allow for less, under

tight conditions.

According to the official statistics (DARES),

after the introduction of the law on working time reduction, actual

hours per week performed by full time employed, fell from 39.6 hours in

1999, to a trough of 37.7 hours in 2002, then gradually went back to

39.1 hours in 2005. In 2016 working hours were of 39.1.

South Korea

South Korea has the fastest shortening working time in the OECD, which is the result of the government's proactive move to lower working hours at all levels to increase leisure and relaxation

time, which introduced the mandatory forty-hour, five-day working week

in 2004 for companies with over 1,000 employees. Beyond regular working

hours, it is legal to demand up to 12 hours of overtime during the

week, plus another 16 hours on weekends.

The 40-hour workweek expanded to companies with 300 employees or more

in 2005, 100 employees or more in 2006, 50 or more in 2007, 20 or more

in 2008 and a full inclusion to all workers nationwide in July 2011. The government has continuously increased public holidays to 16 days in 2013, more than the 10 days of the United States and double that of the United Kingdom's 8 days. Despite those efforts, South Korea's work hours are still relatively long, with an average 2,163 hours per year in 2012.

Japan

Work hours in Japan are decreasing, but many Japanese still work long hours.

Recently, Japan's Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (MHLW) issued a

draft report recommending major changes to the regulations that govern

working hours. The centerpiece of the proposal is an exemption from

overtime pay for white-collar workers. Japan

has enacted an 8-hour work day and 40-hour work week (44 hours in

specified workplaces). The overtime limits are: 15 hours a week, 27

hours over two weeks, 43 hours over four weeks, 45 hours a month, 81

hours over two months and 120 hours over three months; however, some

workers get around these restrictions by working several hours a day

without 'clocking in' whether physically or metaphorically. The overtime allowance should not be lower than 125% and not more than 150% of the normal hourly rate.

Mexico

Mexican

laws mandate a maximum of 48 hours of work per week, but they are rarely

observed or enforced due to loopholes in the law, the volatility of labor rights in Mexico, and its underdevelopment relative to other members countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Indeed, private sector employees often work overtime without receiving

overtime compensation. Fear of unemployment and threats by employers

explain in part why the 48-hour work week is disregarded.

Colombia

Articles

161 to 167 of the Substantive Work Code in Colombia provide for a

maximum of 48 hours of work a week. Also, the law notes that workdays

should be divided into 2 sections to allow a break, usually given as the

meal time which is not counted as work. Typically, there is a 2-hours break for lunch that starts from 12:00 through 14:00.

Australia

In

Australia, between 1974 and 1997 no marked change took place in the

average amount of time spent at work by Australians of "prime working

age" (that is, between 25 and 54 years of age). Throughout this period,

the average time spent at work by prime working-age Australians

(including those who did not spend any time at work) remained stable at

between 27 and 28 hours per week. This unchanging average, however,

masks a significant redistribution of work from men to women. Between

1974 and 1997, the average time spent at work by prime working-age

Australian men fell from 45 to 36 hours per week, while the average time

spent at work by prime working-age Australian women rose from 12 to 19

hours per week. In the period leading up to 1997, the amount of time

Australian workers spent at work outside the hours of 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

on weekdays also increased.

In 2009, a rapid increase in the number of working hours was

reported in a study by The Australia Institute. The study found the

average Australian worked 1855 hours per year at work. According to

Clive Hamilton of The Australia Institute, this surpasses even Japan.

The Australia Institute believes that Australians work the highest

number of hours in the developed world.

From January 1, 2010, Australia enacted a 38-hour workweek in

accordance with the Fair Work Act 2009, with an allowance for additional

hours as overtime.

The vast majority of full-time employees in Australia work

additional overtime hours. A 2015 survey found that of Australia's 7.7

million full-time workers, 5 million put in more than 40 hours a week,

including 1.4 million who worked more than 50 hours a week and 270,000

who put in more than 70 hours.

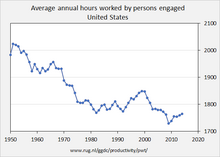

United States

In

2016, the average man employed full-time worked 8.4 hours per work day,

and the average woman employed full-time worked 7.8 hours per work day.

There is no mandatory minimum amount of paid time off for sickness or

holiday but the majority of full time civilian workers have access to

paid vacation time. Because of the pressure of working, time is increasingly viewed as a commodity.

Average annual hours worked by persons engaged United States

Recent history

By 1946 the United States government had inaugurated the 40-hour work week for all federal employees.

Beginning in 1950, under the Truman Administration, the United States

became the first known industrialized nation to explicitly (albeit

secretly) and permanently forswear a reduction of working time. Given

the military-industrial requirements of the Cold War, the authors of the

then secret National Security Council Report 68 (NSC-68)

proposed the US government undertake a massive permanent national

economic expansion that would let it "siphon off" a part of the economic

activity produced to support an ongoing military buildup to contain the

Soviet Union. In his 1951 Annual Message to the Congress, President Truman stated:

In terms of manpower, our present defense targets will require an increase of nearly one million men and women in the armed forces within a few months, and probably not less than four million more in defense production by the end of the year. This means that an additional 8 percent of our labor force, and possibly much more, will be required by direct defense needs by the end of the year. These manpower needs will call both for increasing our labor force by reducing unemployment and drawing in women and older workers, and for lengthening hours of work in essential industries.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average non-farm private sector employee worked 34.5 hours per week as of June 2012.

As President Truman’s 1951 message had predicted, the share of

working women rose from 30 percent of the labor force in 1950 to 47

percent by 2000 – growing at a particularly rapid rate during the 1970s. According to a Bureau of Labor Statistics

report issued May 2002, "In 1950, the overall participation rate of

women was 34 percent. ... The rate rose to 38 percent in 1960, 43

percent in 1970, 52 percent in 1980, and 58 percent in 1990 and reached

60 percent by 2000. The overall labor force participation rate of women

is projected to attain its highest level in 2010, at 62 percent.”

The inclusion of women in the work force can be seen as symbolic of

social progress as well as of increasing American productivity and hours

worked.

Between 1950 and 2007 official price inflation was measured to

861 percent. President Truman, in his 1951 message to Congress,

predicted correctly that his military buildup "will cause intense and

mounting inflationary pressures." Using the data provided by the United

State Bureau of Labor Statistics, Erik Rauch has estimated productivity

to have increased by nearly 400%.

According to Rauch, "if productivity means anything at all, a worker

should be able to earn the same standard of living as a 1950 worker in

only 11 hours per week."

In the United States,

the working time for upper-income professionals has increased compared

to 1965, while total annual working time for low-skill, low-income

workers has decreased. This effect is sometimes called the "leisure gap".

The average working time of married couples – of both spouses taken together – rose from 56 hours in 1969 to 67 hours in 2000.

Overtime rules

Many

professional workers put in longer hours than the forty-hour standard.

In professional industries like investment banking and large law firms, a

forty-hour workweek is considered inadequate and may result in job loss

or failure to be promoted. Medical residents in the United States routinely work long hours as part of their training.

Workweek policies are not uniform in the U.S. Many compensation arrangements are legal, and three of the most common are wage, commission, and salary

payment schemes. Wage earners are compensated on a per-hour basis,

whereas salaried workers are compensated on a per-week or per-job basis,

and commission workers get paid according to how much they produce or

sell.

Under most circumstances, wage earners and lower-level employees

may be legally required by an employer to work more than forty hours in a

week; however, they are paid extra for the additional work. Many

salaried workers and commission-paid sales staff are not covered by

overtime laws. These are generally called "exempt" positions, because

they are exempt from federal and state laws that mandate extra pay for

extra time worked. The rules are complex, but generally exempt workers are executives, professionals, or sales staff.

For example, school teachers are not paid extra for working extra

hours. Business owners and independent contractors are considered

self-employed, and none of these laws apply to them.

Generally, workers are paid time-and-a-half,

or 1.5 times the worker's base wage, for each hour of work past forty.

California also applies this rule to work in excess of eight hours per

day, but exemptions and exceptions significantly limit the applicability of this law.

In some states, firms are required to pay double-time, or

twice the base rate, for each hour of work past 60, or each hour of work

past 12 in one day in California, also subject to numerous exemptions

and exceptions. This provides an incentive

for companies to limit working time, but makes these additional hours

more desirable for the worker. It is not uncommon for overtime hours to

be accepted voluntarily by wage-earning workers. Unions

often treat overtime as a desirable commodity when negotiating how

these opportunities shall be partitioned among union members.

Brazil

The work time in Brazil

is 44 hours per week, usually 8 hours per day and 4 hours on Saturday

or 8.8 hours per day. On duty/no meal break jobs are 6 hours per day.

Public servants work 40 hours a week.

It is worth noting that in Brazil meal time is not usually

counted as work. There is a 1-hour break for lunch and work schedule is

typically 8:00 or 9:00–noon, 13:00–18:00. In larger cities people have

lunch meal on/near the work site, while in smaller cities a sizable

fraction of the employees might go home for lunch.

A 30-day vacation is mandatory by law and there are about 13 to 15 holidays a year, depending on the municipality.

Mainland China

China adopted a 40-hour week, eliminating half-day work on Saturdays. However, this rule has never been truly enforced, and unpaid or underpaid overtime working is common practice in China.

Traditionally, Chinese have worked long hours, and this has led

to many deaths from overwork, with the state media reporting in 2014

that 600,000 people were dying suddenly annually, some of them were

dying from overwork. Despite this, work hours have reportedly been

falling for about three decades due to rising productivity, better labor

laws, and the spread of the two-day weekend. The trend has affected

both factories and white-collar companies that have been responding to

growing demands for easier work schedules.

The “996” work schedule, as it is known, is where employees work from 9

a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week, excluding two hours of lunch & nap

during the noon and one hour of supper in the evening.

Alibaba founder Jack (Yun) Ma, and JD.Com founder Richard (Qiangdong)

Liu both praise the 996 schedule, saying such a schedule has helped

Chinese tech giants like Alibaba and Tencent grow to become what they

are today.

Hong Kong, China

Hong Kong has no legislation regarding maximum and normal working hours.

The average weekly working hours of full-time employees in Hong Kong is 49 hours. According to the Price and Earnings Report 2012 conducted by UBS,

while the global and regional average were 1,915 and 2,154 hours per

year respectively, the average working hours in Hong Kong is 2,296 hours

per year, which ranked the fifth longest yearly working hours among 72

countries under study.

In addition, from the survey conducted by the Public Opinion Study

Group of the University of Hong Kong, 79% of the respondents agree that

the problem of overtime work in Hong Kong is "severe", and 65% of the

respondents support the legislation on the maximum working hours. In Hong Kong, 70% of surveyed do not receive any overtime remuneration.

These show that people in Hong Kong concerns the working time issues.

As Hong Kong implemented the minimum wage law in May 2011, the Chief

Executive, Donald Tsang, of the Special Administrative Region pledged that the government will standardize working hours in Hong Kong.

On 26 November 2012, the Labour Department of the HKSAR released

the "Report of the policy study on standard working hours". The report

covers three major areas, including: (1) the regimes and experience of

other places in regulating working hours, (2) latest working time

situations of employees in different sectors, and (3) estimation of the

possible impact of introducing standard working hour in Hong Kong.

Under the selected parameters, from most loosen to most stringent, the

estimated increase in labour cost vary from 1.1 billion to 55 billion

HKD, and affect 957,100 (36.7% of total employees) to 2,378,900 (91.1%

of total) employees.

Various sectors of the community show concerns about the standard

working hours in Hong Kong. The points are summarized as below:

Opinions from various sectors

Labor organizations

Hong

Kong Catholic Commission For Labour Affairs urges the government to

legislate the standard working hours in Hong Kong, and suggests a 44

hours standard, 54 hours maximum working hours in a week. The

organization thinks that long working time adversely affects the family

and social life and health of employees; it also indicates that the

current Employment Ordinance does not regulate overtime pays, working

time limits nor rest day pays, which can protect employees rights.

Generally,

business sector agrees that it is important to achieve work-life

balance, but does not support a legislation to regulate working hours

limit. They believe "standard working hours" is not the best way to

achieve work-life balance and the root cause of the long working hours

in Hong Kong is due to insufficient labor supply. The Managing Director

of Century Environmental Services Group, Catherine Yan, said "Employees

may want to work more to obtain a higher salary due to financial

reasons. If standard working hour legislation is passed, employers will

need to pay a higher salary to employees, and hence the employers may

choose to segment work tasks to employer more part time employees

instead of providing overtime pay to employees." She thinks this will

lead to a situation that the employees may need to find two part-time

jobs to earn their living, making them wasting more time on

transportation from one job to another.

The Chairman of the Hong Kong General Chamber of Commerce, Chow Chung-kong

believes that it is so difficult to implement standard working hours

that apply “across-the-board”, specifically, to accountants and

barristers.

In addition, he believes that standard working hours may decrease

individual employees' working hours and would not increase their actual

income. It may also lead to an increase of number of part-timers in the

labor market.

According to a study conducted jointly by the Business, Economic

and Public Affairs Research Centre and Enterprise and Social Development

Research Centre of Hong Kong Shue Yan University, 16% surveyed

companies believe that a standard working hours policy can be

considered, and 55% surveyed think that it would be difficult to

implement standard working hours in businesses.

Employer representative in the Labour Advisory Board, Stanley

Lau, said that standard working hours will completely alter the business

environment of Hong Kong, affect small and medium enterprise

and weaken competitiveness of businesses. He believes that the

government can encourage employers to pay overtime salary, and there is

no need to regulate standard working hours.

Political parties

On 17–18 October 2012, the Legislative Council members in Hong Kong debated on the motion "legislation for the regulation of working hours". Cheung Kwok-che

proposed the motion "That is the Council urges the Government to

introduce a bill on the regulation of working hours within this

legislative session, the contents of which must include the number of

standard weekly hours and overtime pay". As the motion was not passed by both functional constituencies and geographical constituencies, it was negatived.

The Hong Kong Federation of Trade Unions

suggested a standard 44-hour work week with overtime pay of 1.5 times

the usual pay. It believes the regulation of standard working hour can

prevent the employers to force employees to work (overtime) without pay.

Elizabeth Quat of the Democratic Alliance for the Betterment and Progress of Hong Kong

(DAB), believed that standard working hours were a labor policy and was

not related to family-friendly policies. The Vice President of Young

DAB, Wai-hung Chan, stated that standard working hours would bring

limitations to small and medium enterprises. He thought that the

government should discuss the topic with the public more before

legislating standard working hours.

The Democratic Party

suggested a 44-hour standard work week and compulsory overtime pay to

help achieve the balance between work, rest and entertainment of people

in Hong Kong.

The Labour Party believed regulating working hours could help achieve a work-life balance.

It suggests an 8-hour work day, a 44-hour standard work week, a 60-hour

maximum work week and an overtime pay of 1.5 times the usual pay.

Poon Siu-ping of Federation of Hong Kong and Kowloon Labour Unions

thought that it is possible to set work hour limit for all industries;

and the regulation on working hours can ensure the overtime payment by

employers to employees, and protect employees’ health.

The Civic party

suggests "to actively study setting weekly standard working hours at 44

hours to align with family-friendly policies" in LegCo Election 2012.

Member of Economic Synergy,

Jeffery Lam, believes that standard working hours would adversely

affect productivity, tense the employer-employee relationship, and

increase the pressure faced by businesses who suffer from inadequate

workers. He does not support the regulation on working hours at its

current situation.

Government

Matthew Cheung Kin-chung, the Secretary for Labour and Welfare Bureau, said the Executive Council

has already received the government report on working hours in June,

and the Labour Advisory Board and the LegCo’s Manpower Panel will

receive the report in late November and December respectively.

On 26 November 2012, the Labour Department released the report, and the

report covered the regimes and experience of practicing standard

working hours in selected regions, current work hour situations in

different industries, and the impact assessment of standard working

hours. Also, Matthew Cheung mentioned that the government will form a

select committee by first quarter of 2013, which will include government

officials, representative of labor unions and employers’ associations,

academics and community leaders, to investigate the related issues. He

also said that it would "perhaps be unrealistic" to put forward a bill

for standard working hours in the next one to two years.

Academics

Yip Siu-fai, Professor of the Department of Social Work and Social Administration of HKU,

has noted that professions such as nursing and accountancy have long

working hours and that this may affect people's social life. He believes

that standard working hours could help to give Hong Kong more

family-friendly workplaces and to increase fertility rates. Randy Chiu,

Professor of the Department of Management of HKBU, has said that introducing standard working hours could avoid excessively long working hours of employees.

He also said that nowadays Hong Kong attains almost full employment,

has a high rental price and severe inflation, recently implemented

minimum wage, and is affected by a gloomy global economy; he also

mentioned that comprehensive considerations on macroeconomic situations

are needed, and emphasized that it is perhaps inappropriate to adopt

working-time regulation as exemplified in other countries to Hong Kong.

Lee Shu-Kam, Associate Professor of the Department of Economics and Finance of HKSYU, believes that standard working hours cannot deliver "work-life balance". He referenced the research

to the US by the University of California, Los Angeles in 1999 and

pointed out that in the industries and regions in which the wage

elasticity is low, the effects of standard working hours on lowering

actual working time and increasing wages is limited: for regions where

the labor supply is inadequate, standard working hours can protect

employees' benefits yet cause unemployment; but for regions (such as

Japan) where the problem does not exist, standard working hours would

only lead to unemployment.

In addition, he said the effect of standard working hours is similar to

that of (for example) giving overtime pay, making employees to favor

overtime work more. In this sense, introducing standard working hours

does not match its principle: to shorten work time and to increase the

recreation time of employees.

He believed that the key point is to help employees to achieve

work-life balance and to get a win-win situation of employers and

employees.

Francis Lui, Head and Professor of the Department of Economics of Hong Kong University of Science and Technology,

believed that standard working hours may not lower work time but

increase unemployment. He used Japan as an example to illustrate that

the implementation of standard working hours lowered productivity per

head and demotivated the economy. He also said that even if the standard

working hours can shorten employees' weekly working hours, they may

need to work for more years to earn sufficient amount of money for retirement, i.e. delay their retirement age. The total working time over the course of a lifetime may not change.

Lok-sang Ho, Professor of Economics and Director of the Centre for Public Policy Studies of Lingnan University,

pointed out that "as different employees perform various jobs and under

different degrees of pressures, it may not appropriate to establish

standard working hours in Hong Kong"; and he proposed a 50-hour maximum

work week to protect workers' health.

Singapore

Singapore

enacts an 8-hour normal work day (9 hours including lunchtime) , a

44-hour normal working week, and a maximum 48-hour work week. It is to

note that if the employee works no more than five days a week, the

employee’s normal working day is 9-hour and the working week is 44

hours. Also, if the number of hours worked of the worker is less than 44

hours every alternate week, the 44-hour weekly limit may be exceeded in

the other week. Yet, this is subjected to the pre-specification in the

service contract and the maximum should not exceed 48 hours per week or

88 hours in any consecutive two week time. In addition, a shift worker

can work up to 12 hours a day, provided that the average working hours

per week do not exceed 44 over a consecutive 3-week time. The overtime

allowance per overtime hour must not be less than 1.5 times of the

employee’s hour basic rates.

Other countries

The Kapauku people of Papua think it is bad luck to work two consecutive days. The !Kung Bushmen work just two-and-a-half days per week, rarely more than six hours per day.

The work week in Samoa is approximately 30 hours,

and although average annual Samoan cash income is relatively low, by

some measures, the Samoan standard of living is quite good.

In India,

particularly in smaller companies, someone generally works for 11 hours

a day and 6 days a week. No overtime is paid for extra time. Law

enforcement is negligible in regulating the working hours. A typical

office will open at 09:00 or 09:30 and officially end the work day at

about 19:00. However, many workers and especially managers will stay

later in the office due to additional work load. However, large Indian

companies and MNC offices located in India tend to follow a 5-day, 8- to

9-hour per day working schedule. The Government of India in some of its

offices also follows a 5-day week schedule.

Nigeria has public servants that work 35 hours per week.

Recent trends

Many modern workplaces are experimenting with accommodating changes in the workforce and the basic structure of scheduled work. Flextime allows office workers to shift their working time away from rush-hour traffic; for example, arriving at 10:00 am and leaving at 6:00 pm. Telecommuting

permits employees to work from their homes or in satellite locations

(not owned by the employer), eliminating or reducing long commute times

in heavily populated areas. Zero-hour contracts establish work contracts without minimum-hour guarantees; workers are paid only for the hours they work.