Natural rights and legal rights are two types of rights.

Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs

of any particular culture or government, and so are universal and

inalienable (they cannot be repealed by human laws, though one can

forfeit their enforcement through one's actions, such as by violating

someone else's rights). Legal rights are those bestowed onto a person by

a given legal system (they can be modified, repealed, and restrained by human laws).

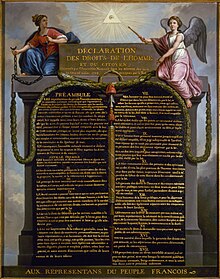

The concept of natural law is related to the concept of natural rights. Natural law first appeared in ancient Greek philosophy, and was referred to by Roman philosopher Cicero. It was subsequently alluded to in the Bible, and then developed in the Middle Ages by Catholic philosophers such as Albert the Great and his pupil Thomas Aquinas. During the Age of Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to challenge the divine right of kings, and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government – and thus legal rights – in the form of classical republicanism. Conversely, the concept of natural rights is used by others to challenge the legitimacy of all such establishments.

The idea of human rights is also closely related to that of natural rights: some acknowledge no difference between the two, regarding them as synonymous, while others choose to keep the terms separate to eliminate association with some features traditionally associated with natural rights. Natural rights, in particular, are considered beyond the authority of any government or international body to dismiss. The 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an important legal instrument enshrining one conception of natural rights into international soft law. Natural rights were traditionally viewed as exclusively negative rights, whereas human rights also comprise positive rights. Even on a natural rights conception of human rights, the two terms may not be synonymous.

The proposition that animals have natural rights is one that gained the interest of philosophers and legal scholars in the 20th century and into the 21st.

The concept of natural law is related to the concept of natural rights. Natural law first appeared in ancient Greek philosophy, and was referred to by Roman philosopher Cicero. It was subsequently alluded to in the Bible, and then developed in the Middle Ages by Catholic philosophers such as Albert the Great and his pupil Thomas Aquinas. During the Age of Enlightenment, the concept of natural laws was used to challenge the divine right of kings, and became an alternative justification for the establishment of a social contract, positive law, and government – and thus legal rights – in the form of classical republicanism. Conversely, the concept of natural rights is used by others to challenge the legitimacy of all such establishments.

The idea of human rights is also closely related to that of natural rights: some acknowledge no difference between the two, regarding them as synonymous, while others choose to keep the terms separate to eliminate association with some features traditionally associated with natural rights. Natural rights, in particular, are considered beyond the authority of any government or international body to dismiss. The 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights is an important legal instrument enshrining one conception of natural rights into international soft law. Natural rights were traditionally viewed as exclusively negative rights, whereas human rights also comprise positive rights. Even on a natural rights conception of human rights, the two terms may not be synonymous.

The proposition that animals have natural rights is one that gained the interest of philosophers and legal scholars in the 20th century and into the 21st.

History

The idea that certain rights are natural or inalienable also has a history dating back at least to the Stoics of late Antiquity, through Catholic law of the early Middle Ages, and descending through the Protestant Reformation and the Age of Enlightenment to today.

The existence of natural rights has been asserted by different individuals on different premises, such as a priori philosophical reasoning or religious principles. For example, Immanuel Kant

claimed to derive natural rights through reason alone. The United

States Declaration of Independence, meanwhile, is based upon the "self-evident" truth that "all men are … endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights".

Likewise, different philosophers and statesmen have designed

different lists of what they believe to be natural rights; almost all

include the right to life and liberty as the two highest priorities. H. L. A. Hart argued that if there are any rights at all, there must be the right to liberty, for all the others would depend upon this. T. H. Green

argued that “if there are such things as rights at all, then, there

must be a right to life and liberty, or, to put it more properly to free

life.” John Locke emphasized "life, liberty and property" as primary. However, despite Locke's influential defense of the right of revolution, Thomas Jefferson substituted "pursuit of happiness" in place of "property" in the United States Declaration of Independence.

Ancient

Stephen Kinzer, a veteran journalist for The New York Times and the author of the book All The Shah's Men, writes in the latter that:

The Zoroastrian religion taught Iranians that citizens have an inalienable right to enlightened leadership and that the duty of subjects is not simply to obey wise kings but also to rise up against those who are wicked. Leaders are seen as representative of God on earth, but they deserve allegiance only as long as they have farr, a kind of divine blessing that they must earn by moral behavior.

The 40 Principal Doctrines of the Epicureans

taught that "in order to obtain protection from other men, any means

for attaining this end is a natural good" (PD 6). They believed in a

contractarian ethics where mortals agree to not harm or be harmed, and

the rules that govern their agreements are not absolute (PD 33), but

must change with circumstances (PD 37-38). The Epicurean doctrines imply

that humans in their natural state enjoy personal sovereignty and that

they must consent to the laws that govern them, and that this consent

(and the laws) can be revisited periodically when circumstances change.

The Stoics held that no one was a slave by nature; slavery was an external condition juxtaposed to the internal freedom of the soul (sui juris). Seneca the Younger wrote:

It is a mistake to imagine that slavery pervades a man's whole being; the better part of him is exempt from it: the body indeed is subjected and in the power of a master, but the mind is independent, and indeed is so free and wild, that it cannot be restrained even by this prison of the body, wherein it is confined.

Of fundamental importance to the development of the idea of natural

rights was the emergence of the idea of natural human equality. As the

historian A.J. Carlyle notes: "There is no change in political theory so

startling in its completeness as the change from the theory of

Aristotle to the later philosophical view represented by Cicero and Seneca.... We think that this cannot be better exemplified than with regard to the theory of the equality of human nature."

Charles H. McIlwain likewise observes that "the idea of the equality of

men is the profoundest contribution of the Stoics to political thought"

and that "its greatest influence is in the changed conception of law

that in part resulted from it." Cicero argues in De Legibus that "we are born for Justice, and that right is based, not upon opinions, but upon Nature."

Modern

One of the first Western thinkers to develop the contemporary idea of natural rights was French theologian Jean Gerson, whose 1402 treatise De Vita Spirituali Animae is considered one of the first attempts to develop what would come to be called modern natural rights theory.

Centuries later, the Stoic doctrine that the "inner part cannot be delivered into bondage" re-emerged in the Reformation doctrine of liberty of conscience. Martin Luther wrote:

Furthermore, every man is responsible for his own faith, and he must see it for himself that he believes rightly. As little as another can go to hell or heaven for me, so little can he believe or disbelieve for me; and as little as he can open or shut heaven or hell for me, so little can he drive me to faith or unbelief. Since, then, belief or unbelief is a matter of every one's conscience, and since this is no lessening of the secular power, the latter should be content and attend to its own affairs and permit men to believe one thing or another, as they are able and willing, and constrain no one by force.

17th-century English philosopher John Locke

discussed natural rights in his work, identifying them as being "life,

liberty, and estate (property)", and argued that such fundamental rights

could not be surrendered in the social contract.

Preservation of the natural rights to life, liberty, and property was

claimed as justification for the rebellion of the American colonies. As George Mason stated in his draft for the Virginia Declaration of Rights,

"all men are born equally free," and hold "certain inherent natural

rights, of which they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their

posterity." Another 17th-century Englishman, John Lilburne (known as Freeborn John), who came into conflict with both the monarchy of King Charles I and the military dictatorship of Oliver Cromwell governed republic, argued for level human basic rights he called "freeborn rights"

which he defined as being rights that every human being is born with,

as opposed to rights bestowed by government or by human law.

The distinction between alienable and unalienable rights was introduced by Francis Hutcheson. In his Inquiry into the Original of Our Ideas of Beauty and Virtue

(1725), Hutcheson foreshadowed the Declaration of Independence,

stating: “For wherever any Invasion is made upon unalienable Rights,

there must arise either a perfect, or external Right to Resistance. . . .

Unalienable Rights are essential Limitations in all Governments.”

Hutcheson, however, placed clear limits on his notion of unalienable

rights, declaring that “there can be no Right, or Limitation of Right,

inconsistent with, or opposite to the greatest public Good." Hutcheson elaborated on this idea of unalienable rights in his A System of Moral Philosophy (1755), based on the Reformation

principle of the liberty of conscience. One could not in fact give up

the capacity for private judgment (e.g., about religious questions)

regardless of any external contracts or oaths to religious or secular

authorities so that right is "unalienable." Hutcheson wrote: "Thus no

man can really change his sentiments, judgments, and inward affections,

at the pleasure of another; nor can it tend to any good to make him

profess what is contrary to his heart. The right of private judgment is

therefore unalienable."

In the German Enlightenment, Hegel

gave a highly developed treatment of this inalienability argument. Like

Hutcheson, Hegel based the theory of inalienable rights on the de facto

inalienability of those aspects of personhood that distinguish persons

from things. A thing, like a piece of property, can in fact be

transferred from one person to another. According to Hegel, the same

would not apply to those aspects that make one a person:

The right to what is in essence inalienable is imprescriptible, since the act whereby I take possession of my personality, of my substantive essence, and make myself a responsible being, capable of possessing rights and with a moral and religious life, takes away from these characteristics of mine just that externality which alone made them capable of passing into the possession of someone else. When I have thus annulled their externality, I cannot lose them through lapse of time or from any other reason drawn from my prior consent or willingness to alienate them.

In discussion of social contract

theory, "inalienable rights" were said to be those rights that could

not be surrendered by citizens to the sovereign. Such rights were

thought to be natural rights, independent of positive law. Some social contract theorists reasoned, however, that in the natural state only the strongest could benefit from their rights. Thus, people form an implicit social contract,

ceding their natural rights to the authority to protect the people from

abuse, and living henceforth under the legal rights of that authority.

Many historical apologies for slavery and illiberal government

were based on explicit or implicit voluntary contracts to alienate any

"natural rights" to freedom and self-determination. The de facto inalienability arguments of Hutcheson and his predecessors provided the basis for the anti-slavery movement

to argue not simply against involuntary slavery but against any

explicit or implied contractual forms of slavery. Any contract that

tried to legally alienate such a right would be inherently invalid.

Similarly, the argument was used by the democratic movement to argue

against any explicit or implied social contracts of subjection (pactum subjectionis) by which a people would supposedly alienate their right of self-government to a sovereign as, for example, in Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes. According to Ernst Cassirer,

There is, at least, one right that cannot be ceded or abandoned: the right to personality...They charged the great logician [Hobbes] with a contradiction in terms. If a man could give up his personality he would cease being a moral being. … There is no pactum subjectionis, no act of submission by which man can give up the state of free agent and enslave himself. For by such an act of renunciation he would give up that very character which constitutes his nature and essence: he would lose his humanity.

These themes converged in the debate about American Independence. While Jefferson was writing the Declaration of Independence, Richard Price

in England sided with the Americans' claim "that Great Britain is

attempting to rob them of that liberty to which every member of society

and all civil communities have a natural and unalienable title." Price again based the argument on the de facto

inalienability of "that principle of spontaneity or self-determination

which constitutes us agents or which gives us a command over our

actions, rendering them properly ours, and not effects of the operation

of any foreign cause." Any social contract or compact allegedly alienating these rights would be non-binding and void, wrote Price:

Neither can any state acquire such an authority over other states in virtue of any compacts or cessions. This is a case in which compacts are not binding. Civil liberty is, in this respect, on the same footing with religious liberty. As no people can lawfully surrender their religious liberty by giving up their right of judging for themselves in religion, or by allowing any human beings to prescribe to them what faith they shall embrace, or what mode of worship they shall practise, so neither can any civil societies lawfully surrender their civil liberty by giving up to any extraneous jurisdiction their power of legislating for themselves and disposing their property.

Price raised a furor of opposition so in 1777 he wrote another tract that clarified his position and again restated the de facto

basis for the argument that the "liberty of men as agents is that power

of self-determination which all agents, as such, possess."

In Intellectual Origins of American Radicalism, Staughton Lynd pulled together these themes and related them to the slavery debate:

Then it turned out to make considerable difference whether one said slavery was wrong because every man has a natural right to the possession of his own body, or because every man has a natural right freely to determine his own destiny. The first kind of right was alienable: thus Locke neatly derived slavery from capture in war, whereby a man forfeited his labor to the conqueror who might lawfully have killed him; and thus Dred Scott was judged permanently to have given up his freedom. But the second kind of right, what Price called "that power of self-determination which all agents, as such, possess," was inalienable as long man remained man. Like the mind's quest for religious truth from which it was derived, self-determination was not a claim to ownership which might be both acquired and surrendered, but an inextricable aspect of the activity of being human.

Meanwhile, in America, Thomas Jefferson "took his division of rights into alienable and unalienable from Hutcheson, who made the distinction popular and important", and in the 1776 United States Declaration of Independence, famously condensed this to:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights...

In the 19th century, the movement to abolish slavery seized this

passage as a statement of constitutional principle, although the U.S.

constitution recognized and protected slavery. As a lawyer, future Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase argued before the Supreme Court in the case of John Van Zandt, who had been charged with violating the Fugitive Slave Act, that:

The law of the Creator, which invests every human being with an inalienable title to freedom, cannot be repealed by any interior law which asserts that man is property.

The concept of inalienable rights was criticized by Jeremy Bentham and Edmund Burke

as groundless. Bentham and Burke, writing in 18th century Britain,

claimed that rights arise from the actions of government, or evolve from

tradition, and that neither of these can provide anything inalienable. (See Bentham's "Critique of the Doctrine of Inalienable, Natural Rights", and Burke's Reflections on the Revolution in France).

Presaging the shift in thinking in the 19th century, Bentham famously

dismissed the idea of natural rights as "nonsense on stilts". By way of

contrast to the views of British nationals Burke and Bentham, the

leading American revolutionary scholar James Wilson condemned Burke's view as "tyranny."

The signers of the Declaration of Independence deemed it a

"self-evident truth" that all men "are endowed by their Creator with

certain unalienable Rights".

In The Social Contract, Jean-Jacques Rousseau claims that the existence of inalienable rights is unnecessary for the existence of a constitution or a set of laws and rights. This idea of a social contract –

that rights and responsibilities are derived from a consensual contract

between the government and the people – is the most widely recognized

alternative.

One criticism of natural rights theory is that one cannot draw norms from facts. This objection is variously expressed as the is-ought problem, the naturalistic fallacy, or the appeal to nature. G.E. Moore, for example, said that ethical naturalism falls prey to the naturalistic fallacy.

Some defenders of natural rights theory, however, counter that the term

"natural" in "natural rights" is contrasted with "artificial" rather

than referring to nature. John Finnis, for example, contends that natural law and natural rights are derived from self-evident principles, not from speculative principles or from facts.

There is also debate as to whether all rights are either natural or legal. Fourth president of the United States James Madison, while representing Virginia in the House of Representatives, believed that there are rights, such as trial by jury, that are social rights, arising neither from natural law nor from positive law (which are the basis of natural and legal rights respectively) but from the social contract from which a government derives its authority.

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) included a discussion of natural rights in his moral and political philosophy.

Hobbes' conception of natural rights extended from his conception of

man in a "state of nature". Thus he argued that the essential natural

(human) right was "to use his own power, as he will himself, for the

preservation of his own Nature; that is to say, of his own Life; and

consequently, of doing any thing, which in his own judgement, and

Reason, he shall conceive to be the aptest means thereunto." (Leviathan. 1, XIV)

Hobbes sharply distinguished this natural "liberty", from natural

"laws", described generally as "a precept, or general rule, found out

by reason, by which a man is forbidden to do, that, which is destructive

of his life, or taketh away the means of preserving his life; and to

omit, that, by which he thinketh it may best be preserved."

In his natural state, according to Hobbes, man's life consisted

entirely of liberties and not at all of laws – "It followeth, that in

such a condition, every man has the right to every thing; even to one

another's body. And therefore, as long as this natural Right of every

man to every thing endureth, there can be no security to any man... of

living out the time, which Nature ordinarily allow men to live."

This would lead inevitably to a situation known as the "war of all against all",

in which human beings kill, steal and enslave others in order to stay

alive, and due to their natural lust for "Gain", "Safety" and

"Reputation". Hobbes reasoned that this world of chaos created by

unlimited rights was highly undesirable, since it would cause human life

to be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short". As such, if humans

wish to live peacefully they must give up most of their natural rights

and create moral obligations in order to establish political and civil society. This is one of the earliest formulations of the theory of government known as the social contract.

Hobbes objected to the attempt to derive rights from "natural law,"

arguing that law ("lex") and right ("jus") though often confused,

signify opposites, with law referring to obligations, while rights refer

to the absence of obligations. Since by our (human) nature, we seek to

maximize our well being, rights are prior to law, natural or

institutional, and people will not follow the laws of nature without

first being subjected to a sovereign power, without which all ideas of right and wrong

are meaningless – "Therefore before the names of Just and Unjust can

have place, there must be some coercive Power, to compel men equally to

the performance of their Covenants..., to make good that Propriety,

which by mutual contract men acquire, in recompense of the universal

Right they abandon: and such power there is none before the erection of

the Commonwealth." (Leviathan. 1, XV)

This marked an important departure from medieval natural law theories which gave precedence to obligations over rights.

John Locke

John Locke (1632 – 1704) was another prominent Western philosopher

who conceptualized rights as natural and inalienable. Like Hobbes, Locke

believed in a natural right to life, liberty, and property. It was once conventional wisdom that Locke greatly influenced the American Revolutionary War

with his writings of natural rights, but this claim has been the

subject of protracted dispute in recent decades. For example, the

historian Ray Forrest Harvey declared that Jefferson and Locke were at

"two opposite poles" in their political philosophy, as evidenced by

Jefferson’s use in the Declaration of Independence of the phrase

"pursuit of happiness" instead of "property." More recently, the eminent

legal historian John Phillip Reid has deplored contemporary scholars’

"misplaced emphasis on John Locke," arguing that American revolutionary

leaders saw Locke as a commentator on established constitutional principles. Thomas Pangle

has defended Locke's influence on the Founding, claiming that

historians who argue to the contrary either misrepresent the classical

republican alternative to which they say the revolutionary leaders

adhered, do not understand Locke, or point to someone else who was

decisively influenced by Locke. This position has also been sustained by Michael Zuckert.

According to Locke there are three natural rights:

- Life: everyone is entitled to live.

- Liberty: everyone is entitled to do anything they want to so long as it doesn't conflict with the first right.

- Estate: everyone is entitled to own all they create or gain through gift or trade so long as it doesn't conflict with the first two rights.

Locke in his central political philosophy believes in a government

that provides what he claims to be basic and natural given rights for

its citizens. These being the right to life, liberty, and property.

Essentially Locke claims that the ideal government will encompass the

preservations of these three rights for all, every single one, of its

citizens. It will provide these rights, and protect them from tyranny

and abuse, giving the power of the government to the people. However,

Locke not only influenced modern democracy, but opened this idea of

rights for all, freedom for all. So, not only did Locke influence the

foundation of modern democracy heavily, but his thought seems to also

connect to the social activism promoted in democracy. Locke acknowledges

that we all have differences, and he believes that those differences do

not grant certain people less freedom.

In developing his concept of natural rights, Locke was influenced by reports of society among Native Americans, whom he regarded as natural peoples who lived in a "state of liberty" and perfect freedom, but "not a state of license". It also informed his conception of social contract.

Although he does not blatantly state it, his position implies that even

in light of our unique characteristics we shouldn't be treated

differently by our neighbors or our rulers. “Locke is arguing that there

is no natural characteristic sufficient to distinguish one person from

another…of, course there are plenty of natural differences between us”

(Haworth 103).

What Haworth takes from Locke is that, John Locke was obsessed with

supporting equality in society, treating everyone as an equal. He does

though highlight our differences with his philosophy showing that we are

all unique and important to society. In his philosophy it's highlighted

that the ideal government should also protect everyone, and provide

rights and freedom to everyone, because we are all important to society.

His ideas then were developed into the movements for freedom from the

British creating our government. However, his implied thought of freedom

for all is applied most heavily in our culture today. Starting with the

civil rights movement, and continuing through women's rights, Locke's

call for a fair government can be seen as the influence in these

movements. His ideas are typically just seen as the foundation for

modern democracy, however, it's not unreasonable to credit Locke with

the social activism throughout the history of America.

By founding this sense of freedom for all, Locke was laying the

groundwork for the equality that occurs today. Despite the apparent

misuse of his philosophy in early American democracy. The Civil Rights

movement and the suffrage movement both called out the state of American

democracy during their challenges to the governments view on equality.

To them it was clear that when the designers of democracy said all, they

meant all people shall receive those natural rights that John Locke

cherished so deeply. “a state also of equality, wherein all the power

and jurisdiction is reciprocal, no one having more than another” (Locke

II,4).

Locke in his papers on natural philosophy clearly states that he wants a

government where all are treated equal in freedoms especially. “Locke’s

views on toleration were very progressive for the time” (Connolly).

Authors such as Jacob Connolly confirm that to them Locke was highly

ahead of his time with all this progressive thinking. That is that his

thought fits our current state of democracy where we strive to make sure

that everyone has a say in the government and everyone has a chance at a

good life. Regardless of race, gender, or social standing starting with

Locke it was made clear not only that the government should provide

rights, but rights to everyone through his social contract.

The social contract is an agreement between members of a country

to live within a shared system of laws. Specific forms of government are

the result of the decisions made by these persons acting in their

collective capacity. Government is instituted to make laws that protect

these three natural rights. If a government does not properly protect

these rights, it can be overthrown.

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (1731–1809) further elaborated on natural rights in his influential work Rights of Man

(1791), emphasizing that rights cannot be granted by any charter

because this would legally imply they can also be revoked and under such

circumstances they would be reduced to privileges:

It is a perversion of terms to say that a charter gives rights. It operates by a contrary effect – that of taking rights away. Rights are inherently in all the inhabitants; but charters, by annulling those rights, in the majority, leave the right, by exclusion, in the hands of a few. … They...consequently are instruments of injustice. The fact therefore must be that the individuals themselves, each in his own personal and sovereign right, entered into a compact with each other to produce a government: and this is the only mode in which governments have a right to arise, and the only principle on which they have a right to exist.

American individualist anarchists

While at first American individualist anarchists adhered to natural rights positions, later in this era led by Benjamin Tucker, some abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's Egoist anarchism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said there were only two rights: "the right of might" and "the right of contract".

He also said, after converting to Egoist individualism, "In times

past... it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It

was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off.... Man's only right to

land is his might over it."

According to Wendy McElroy:

In adopting Stirnerite egoism (1886), Tucker rejected natural rights which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism. This rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself. So bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter, Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change significantly.

Several periodicals were "undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism, including I published by C.L. Swartz, edited by W.E. Gordak and J.W. Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand, and The Eagle and The Serpent,

issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language

egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle 'A

Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology'". Among those American anarchists who adhered to egoism include Benjamin Tucker, John Beverley Robinson, Steven T. Byington, Hutchins Hapgood, James L. Walker, Victor Yarros and E.H. Fulton.

Contemporary

Many documents now echo the phrase used in the United States Declaration of Independence. The preamble to the 1948 United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights

asserts that rights are inalienable: "recognition of the inherent

dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the

human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the

world." Article 1, § 1 of the California Constitution recognizes inalienable rights, and articulated some

(not all) of those rights as "defending life and liberty, acquiring,

possessing, and protecting property, and pursuing and obtaining safety,

happiness, and privacy."

However, there is still much dispute over which "rights" are truly

natural rights and which are not, and the concept of natural or

inalienable rights is still controversial to some.

Erich Fromm

argued that some powers over human beings could be wielded only by God,

and that if there were no God, no human beings could wield these

powers.

Contemporary political philosophies continuing the classical liberal tradition of natural rights include libertarianism, anarcho-capitalism and Objectivism, and include amongst their canon the works of authors such as Robert Nozick, Ludwig von Mises, Ayn Rand, and Murray Rothbard. A libertarian view of inalienable rights is laid out in Morris and Linda Tannehill's The Market for Liberty,

which claims that a man has a right to ownership over his life and

therefore also his property, because he has invested time (i.e. part of

his life) in it and thereby made it an extension of his life. However,

if he initiates force against and to the detriment of another man, he

alienates himself from the right to that part of his life which is

required to pay his debt: "Rights are not inalienable, but only

the possessor of a right can alienate himself from that right – no one

else can take a man's rights from him."

Various definitions of inalienability include non-relinquishability, non-salability, and non-transferability. This concept has been recognized by libertarians as being central to the question of voluntary slavery, which Murray Rothbard dismissed as illegitimate and even self-contradictory. Stephan Kinsella argues that "viewing rights as alienable is perfectly consistent with – indeed, implied by – the libertarian non-aggression principle. Under this principle, only the initiation of force is prohibited; defensive, restitutive, or retaliatory force is not."

Various philosophers have created different lists of rights they

consider to be natural. Proponents of natural rights, in particular

Hesselberg and Rothbard, have responded that reason can be applied to separate truly axiomatic

rights from supposed rights, stating that any principle that requires

itself to be disproved is an axiom. Critics have pointed to the lack of

agreement between the proponents as evidence for the claim that the idea

of natural rights is merely a political tool.

Hugh Gibbons has proposed a descriptive argument based on human

biology. His contention is that Human Beings were other-regarding as a

matter of necessity, in order to avoid the costs of conflict. Over time

they developed expectations that individuals would act in certain ways

which were then prescribed by society (duties of care etc.) and that

eventually crystallized into actionable rights.