From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Carnot cycle is a theoretical thermodynamic cycle proposed by Carnot in 1824 and expanded upon by others in the 1830s and 1840s. It provides an upper limit on the efficiency that any classical thermodynamic engine can achieve during the conversion of heat into work, or conversely, the efficiency of a refrigeration system in creating a temperature difference (e.g. refrigeration) by the application of work to the system. It is not an actual thermodynamic cycle but is a theoretical construct.

Every single thermodynamic system exists in a particular state. When a system is taken through a series of different states and finally returned to its initial state, a thermodynamic cycle is said to have occurred. In the process of going through this cycle, the system may perform work on its surroundings, thereby acting as a heat engine. A system undergoing a Carnot cycle is called a Carnot heat engine, although such a "perfect" engine is only a theoretical construct and cannot be built in practice.[1] However, a microscopic Carnot heat engine has been designed and run.[2]

Essentially, there are two systems at temperatures Th and Tc (hot and cold respectively), which are so large that their temperatures are practically unaffected by a single cycle. As such, they are called "heat reservoirs". Since the cycle is reversible, there is no generation of entropy during the cycle; entropy is conserved. During the cycle, an arbitrary amount of entropy ΔS is extracted from the hot reservoir, and deposited in the cold reservoir. Since there is no volume change in either reservoir, they do no work, and during the cycle, an amount of energy ThΔS is extracted from the hot reservoir and a smaller amount of energy TcΔS is deposited in the cold reservoir. The difference in the two energies (Th-Tc)ΔS is equal to the work done by the engine.

Stages

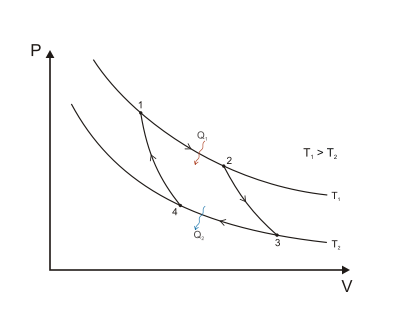

Figure 1: A Carnot cycle illustrated on a PV diagram to illustrate the work done.

The Carnot cycle when acting as a heat engine consists of the following steps:

- Reversible isothermal expansion of the gas at the "hot" temperature, T1 (isothermal heat addition or absorption).

During this step (1 to 2 on Figure 1, A to B in Figure 2) the gas is

allowed to expand and it does work on the surroundings. The temperature

of the gas does not change during the process, and thus the expansion is

isothermal. The gas expansion is propelled by absorption of heat energy

Q1 from the high temperature reservoir and results in an increase of entropy of the gas in the amount

.

- Isentropic (reversible adiabatic) expansion of the gas (isentropic work output). For this step (2 to 3 on Figure 1, B to C in Figure 2) the mechanisms of the engine are assumed to be thermally insulated, thus they neither gain nor lose heat (an adiabatic process). The gas continues to expand, doing work on the surroundings, and losing an amount of internal energy equal to the work that leaves the system. The gas expansion causes it to cool to the "cold" temperature, T2. The entropy remains unchanged.

- Reversible isothermal compression of the gas at the "cold" temperature, T2. (isothermal heat rejection) (3 to 4 on Figure 1, C to D on Figure 2) Now the surroundings do work on the gas, causing an amount of heat energy Q2 to leave the system to the low temperature reservoir and the entropy of the system decreases in the amount

. (This is the same amount of entropy absorbed in step 1, as can be seen from the Clausius inequality.)

- Isentropic compression of the gas (isentropic work input). (4 to 1 on Figure 1, D to A on Figure 2) Once again the mechanisms of the engine are assumed to be thermally insulated, and frictionless, hence reversible. During this step, the surroundings do work on the gas, increasing its internal energy and compressing it, causing the temperature to rise to T1 due solely to the work added to the system, but the entropy remains unchanged. At this point the gas is in the same state as at the start of step 1.

,

.

and

and  are both lower and in fact are in the same ratio as

are both lower and in fact are in the same ratio as  .

.The pressure-volume graph

When the Carnot cycle is plotted on a pressure volume diagram, the isothermal stages follow the isotherm lines for the working fluid, adiabatic stages move between isotherms and the area bounded by the complete cycle path represents the total work that can be done during one cycle.Properties and significance

The temperature-entropy diagram

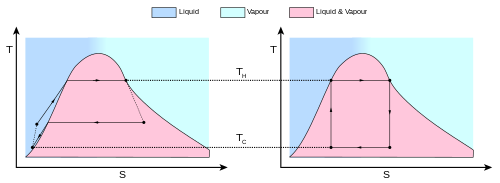

Figure 2: A Carnot cycle acting as a heat engine, illustrated on a

temperature-entropy diagram. The cycle takes place between a hot

reservoir at temperature TH and a cold reservoir at temperature TC. The vertical axis is temperature, the horizontal axis is entropy.

A generalized thermodynamic cycle taking place between a hot reservoir at temperature TH and a cold reservoir at temperature TC. By the second law of thermodynamics, the cycle cannot extend outside the temperature band from TC to TH. The area in red QC

is the amount of energy exchanged between the system and the cold

reservoir. The area in white W is the amount of work energy exchanged by

the system with its surroundings. The amount of heat exchanged with the

hot reservoir is the sum of the two. If the system is behaving as an

engine, the process moves clockwise around the loop, and moves

counter-clockwise if it is behaving as a refrigerator. The efficiency to

the cycle is the ratio of the white area (work) divided by the sum of

the white and red areas (heat absorbed from the hot reservoir).

The behaviour of a Carnot engine or refrigerator is best understood by using a temperature-entropy diagram (TS diagram), in which the thermodynamic state is specified by a point on a graph with entropy (S) as the horizontal axis and temperature (T) as the vertical axis. For a simple closed system (control mass analysis), any point on the graph will represent a particular state of the system. A thermodynamic process will consist of a curve connecting an initial state (A) and a final state (B). The area under the curve will be:

A Carnot cycle taking place between a hot reservoir at temperature TH and a cold reservoir at temperature TC.

The Carnot cycle

A visualization of the Carnot cycle

Evaluation of the above integral is particularly simple for the Carnot cycle. The amount of energy transferred as work is

is defined to be:

is defined to be:is the work done by the system (energy exiting the system as work),

is the heat taken from the system (heat energy leaving the system),

is the heat put into the system (heat energy entering the system),

is the absolute temperature of the cold reservoir, and

is the absolute temperature of the hot reservoir.

is the maximum system entropy

is the minimum system entropy

The Reversed Carnot cycle

The Carnot heat-engine cycle described is a totally reversible cycle. That is, all the processes that comprise it can be reversed, in which case it becomes the Carnot refrigeration cycle. This time, the cycle remains exactly the same except that the directions of any heat and work interactions are reversed. Heat is absorbed from the low-temperature reservoir, heat is rejected to a high-temperature reservoir, and a work input is required to accomplish all this. The P-V diagram of the reversed Carnot cycle is the same as for the Carnot cycle except that the directions of the processes are reversed.[3]Carnot's theorem

It can be seen from the above diagram, that for any cycle operating between temperatures and

and  , none can exceed the efficiency of a Carnot cycle.

, none can exceed the efficiency of a Carnot cycle.

A real engine (left) compared to the Carnot cycle (right). The entropy

of a real material changes with temperature. This change is indicated by

the curve on a T-S diagram. For this figure, the curve indicates a

vapor-liquid equilibrium (See Rankine cycle).

Irreversible systems and losses of energy (for example, work due to

friction and heat losses) prevent the ideal from taking place at every

step.

Carnot's theorem is a formal statement of this fact: No engine operating between two heat reservoirs can be more efficient than a Carnot engine operating between those same reservoirs. Thus, Equation 3 gives the maximum efficiency possible for any engine using the corresponding temperatures. A corollary to Carnot's theorem states that: All reversible engines operating between the same heat reservoirs are equally efficient. Rearranging the right side of the equation gives what may be a more easily understood form of the equation. Namely that the theoretical maximum efficiency of a heat engine equals the difference in temperature between the hot and cold reservoir divided by the absolute temperature of the hot reservoir. Looking at this formula an interesting fact becomes apparent; Lowering the temperature of the cold reservoir will have more effect on the ceiling efficiency of a heat engine than raising the temperature of the hot reservoir by the same amount. In the real world, this may be difficult to achieve since the cold reservoir is often an existing ambient temperature.

In other words, maximum efficiency is achieved if and only if no new entropy is created in the cycle, which would be the case if e.g. friction leads to dissipation of work into heat. In that case the cycle is not reversible and the Clausius theorem becomes an inequality rather than an equality. Otherwise, since entropy is a state function, the required dumping of heat into the environment to dispose of excess entropy leads to a (minimal) reduction in efficiency. So Equation 3 gives the efficiency of any reversible heat engine.

In mesoscopic heat engines, work per cycle of operation fluctuates due to thermal noise. For the case when work and heat fluctuations are counted, there is exact equality that relates average of exponents of work performed by any heat engine and the heat transfer from the hotter heat bath.[4]

Efficiency of real heat engines

Carnot realized that in reality it is not possible to build a thermodynamically reversible engine, so real heat engines are even less efficient than indicated by Equation 3. In addition, real engines that operate along this cycle are rare. Nevertheless, Equation 3 is extremely useful for determining the maximum efficiency that could ever be expected for a given set of thermal reservoirs.Although Carnot's cycle is an idealisation, the expression of Carnot efficiency is still useful. Consider the average temperatures,

For the Carnot cycle, or its equivalent, the average value 〈TH〉 will equal the highest temperature available, namely TH, and 〈TC〉 the lowest, namely TC. For other less efficient cycles, 〈TH〉 will be lower than TH, and 〈TC〉 will be higher than TC. This can help illustrate, for example, why a reheater or a regenerator can improve the thermal efficiency of steam power plants—and why the thermal efficiency of combined-cycle power plants (which incorporate gas turbines operating at even higher temperatures) exceeds that of conventional steam plants. The first prototype of the diesel engine was based on the Carnot cycle.