From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Entropy is the only quantity in the physical sciences (apart from certain rare interactions in particle physics; see below) that requires a particular direction for time, sometimes called an arrow of time. As one goes "forward" in time, the second law of thermodynamics says, the entropy of an isolated system can increase, but not decrease. Hence, from one perspective, entropy measurement is a way of distinguishing the past from the future. However, in thermodynamic systems that are not closed, entropy can decrease with time: many systems, including living systems, reduce local entropy at the expense of an environmental increase, resulting in a net increase in entropy. Examples of such systems and phenomena include the formation of typical crystals, the workings of a refrigerator and living organisms, used in thermodynamics.

Entropy, like temperature, is an abstract concept, yet, like temperature, everyone has an intuitive sense of the effects of entropy. Watching a movie, it is usually easy to determine whether it is being run forward or in reverse. When run in reverse, broken glasses spontaneously reassemble; smoke goes down a chimney; wood "unburns", cooling the environment; and ice "unmelts", warming the environment. No physical laws are broken in the reverse movie except the second law of thermodynamics, which reflects the time-asymmetry of entropy. An intuitive understanding of the irreversibility of certain physical phenomena (and subsequent creation of entropy) allows one to make this determination.

By contrast, all physical processes occurring at the atomic level, such as mechanics, do not pick out an arrow of time. Going forward in time, an atom might move to the left, whereas going backward in time the same atom might move to the right; the behavior of the atom is not qualitatively different in either case. It would, however, be an astronomically improbable event if a macroscopic amount of gas that originally filled a container evenly spontaneously shrunk to occupy only half the container.

Certain subatomic interactions involving the weak nuclear force violate the conservation of parity, but only very rarely,[citation needed] According to the CPT theorem, this means they should also be time irreversible, and so establish an arrow of time. This, however, is neither linked to the thermodynamic arrow of time, nor has anything to do with our daily experience of time irreversibility.[1]

| Unsolved problem in physics:

Arrow of time: Why did the universe have such low entropy in the past, resulting in the distinction between past and future and the second law of thermodynamics?

(more unsolved problems in physics) |

Overview

The Second Law of Thermodynamics allows for the entropy to remain the same regardless of the direction of time. If the entropy is constant in either direction of time, there would be no preferred direction. However, the entropy can only be a constant if the system is in the highest possible state of disorder, such as a gas that always was, and always will be, uniformly spread out in its container. The existence of a thermodynamic arrow of time implies that the system is highly ordered in one time direction only, which would by definition be the "past". Thus this law is about the boundary conditions rather than the equations of motion of our world.The Second Law of Thermodynamics is statistical in nature, and therefore its reliability arises from the huge number of particles present in macroscopic systems. It is not impossible, in principle, for all 6 × 1023 atoms in a mole of a gas to spontaneously migrate to one half of a container; it is only fantastically unlikely—so unlikely that no macroscopic violation of the Second Law has ever been observed. T Symmetry is the symmetry of physical laws under a time reversal transformation. Although in restricted contexts one may find this symmetry, the observable universe itself does not show symmetry under time reversal, primarily due to the second law of thermodynamics.

The thermodynamic arrow is often linked to the cosmological arrow of time, because it is ultimately about the boundary conditions of the early universe. According to the Big Bang theory, the Universe was initially very hot with energy distributed uniformly. For a system in which gravity is important, such as the universe, this is a low-entropy state (compared to a high-entropy state of having all matter collapsed into black holes, a state to which the system may eventually evolve). As the Universe grows, its temperature drops, which leaves less energy available to perform work in the future than was available in the past. Additionally, perturbations in the energy density grow (eventually forming galaxies and stars). Thus the Universe itself has a well-defined thermodynamic arrow of time. But this does not address the question of why the initial state of the universe was that of low entropy. If cosmic expansion were to halt and reverse due to gravity, the temperature of the Universe would once again grow hotter, but its entropy would also continue to increase due to the continued growth of perturbations and the eventual black hole formation,[2] until the latter stages of the Big Crunch when entropy would be lower than now.[citation needed]

An example of apparent irreversibility

Consider the situation in which a large container is filled with two separated liquids, for example a dye on one side and water on the other. With no barrier between the two liquids, the random jostling of their molecules will result in them becoming more mixed as time passes. However, if the dye and water are mixed then one does not expect them to separate out again when left to themselves. A movie of the mixing would seem realistic when played forwards, but unrealistic when played backwards.If the large container is observed early on in the mixing process, it might be found only partially mixed. It would be reasonable to conclude that, without outside intervention, the liquid reached this state because it was more ordered in the past, when there was greater separation, and will be more disordered, or mixed, in the future.

Now imagine that the experiment is repeated, this time with only a few molecules, perhaps ten, in a very small container. One can easily imagine that by watching the random jostling of the molecules it might occur — by chance alone — that the molecules became neatly segregated, with all dye molecules on one side and all water molecules on the other. That this can be expected to occur from time to time can be concluded from the fluctuation theorem; thus it is not impossible for the molecules to segregate themselves. However, for a large numbers of molecules it is so unlikely that one would have to wait, on average, many times longer than the age of the universe for it to occur. Thus a movie that showed a large number of molecules segregating themselves as described above would appear unrealistic and one would be inclined to say that the movie was being played in reverse. See Boltzmann's Second Law as a law of disorder.

Mathematics of the arrow

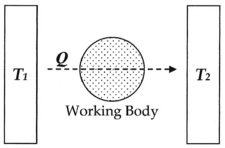

The mathematics behind the arrow of time, entropy, and basis of the second law of thermodynamics derive from the following set-up, as detailed by Carnot (1824), Clapeyron (1832), and Clausius (1854):

In this diagram, one can calculate the entropy change ΔS for the passage of the quantity of heat Q from the temperature T1, through the "working body" of fluid (see heat engine), which was typically a body of steam, to the temperature T2. Moreover, one could assume, for the sake of argument, that the working body contains only two molecules of water.

Next, if we make the assignment, as originally done by Clausius:

Maxwell's demon

In 1867, James Clerk Maxwell introduced a now-famous thought experiment that highlighted the contrast between the statistical nature of entropy and the deterministic nature of the underlying physical processes. This experiment, known as Maxwell's demon, consists of a hypothetical "demon" that guards a trapdoor between two containers filled with gases at equal temperatures. By allowing fast molecules through the trapdoor in only one direction and only slow molecules in the other direction, the demon raises the temperature of one gas and lowers the temperature of the other, apparently violating the Second Law.Maxwell's thought experiment was only resolved in the 20th century by Leó Szilárd, Charles H. Bennett, Seth Lloyd and others. The key idea is that the demon itself necessarily possesses a non-negligible amount of entropy that increases even as the gases lose entropy, so that the entropy of the system as a whole increases. This is because the demon has to contain many internal "parts" (essentially: a memory space to store information on the gas molecules) if it is to perform its job reliably, and therefore must be considered a macroscopic system with non-vanishing entropy. An equivalent way of saying this is that the information possessed by the demon on which atoms are considered fast or slow, can be considered a form of entropy known as information entropy.

Correlations

An important difference between the past and the future is that in any system (such as a gas of particles) its initial conditions are usually such that its different parts are uncorrelated, but as the system evolves and its different parts interact with each other, they become correlated.[3] For example, whenever dealing with a gas of particles, it is always assumed that its initial conditions are such that there is no correlation between the states of different particles (i.e. the speeds and locations of the different particles are completely random, up to the need to conform with the macrostate of the system). This is closely related to the Second Law of Thermodynamics.Take for example (experiment A) a closed box that is, at the beginning, half-filled with ideal gas. As time passes, the gas obviously expands to fill the whole box, so that the final state is a box full of gas. This is an irreversible process, since if the box is full at the beginning (experiment B), it does not become only half-full later, except for the very unlikely situation where the gas particles have very special locations and speeds. But this is precisely because we always assume that the initial conditions are such that the particles have random locations and speeds. This is not correct for the final conditions of the system, because the particles have interacted between themselves, so that their locations and speeds have become dependent on each other, i.e. correlated. This can be understood if we look at experiment A backwards in time, which we'll call experiment C: now we begin with a box full of gas, but the particles do not have random locations and speeds; rather, their locations and speeds are so particular, that after some time they all move to one half of the box, which is the final state of the system (this is the initial state of experiment A, because now we're looking at the same experiment backwards!). The interactions between particles now do not create correlations between the particles, but in fact turn them into (at least seemingly) random, "canceling" the pre-existing correlations. The only difference between experiment C (which defies the Second Law of Thermodynamics) and experiment B (which obeys the Second Law of Thermodynamics) is that in the former the particles are uncorrelated at the end, while in the latter the particles are uncorrelated at the beginning.[citation needed]

In fact, if all the microscopic physical processes are reversible (see discussion below), then the Second Law of Thermodynamics can be proven for any isolated system of particles with initial conditions in which the particles states are uncorrelated. To do this, one must acknowledge the difference between the measured entropy of a system—which depends only on its macrostate (its volume, temperature etc.)—and its information entropy (also called Kolmogorov complexity),[4] which is the amount of information (number of computer bits) needed to describe the exact microstate of the system. The measured entropy is independent of correlations between particles in the system, because they do not affect its macrostate, but the information entropy does depend on them, because correlations lower the randomness of the system and thus lowers the amount of information needed to describe it.[5] Therefore, in the absence of such correlations the two entropies are identical, but otherwise the information entropy is smaller than the measured entropy, and the difference can be used as a measure of the amount of correlations.

Now, by Liouville's theorem, time-reversal of all microscopic processes implies that the amount of information needed to describe the exact microstate of an isolated system (its information-theoretic joint entropy) is constant in time. This joint entropy is equal to the marginal entropy (entropy assuming no correlations) plus the entropy of correlation (mutual entropy, or its negative mutual information). If we assume no correlations between the particles initially, then this joint entropy is just the marginal entropy, which is just the initial thermodynamic entropy of the system, divided by Boltzmann's constant. However, if these are indeed the initial conditions (and this is a crucial assumption), then such correlations form with time. In other words, there is a decreasing mutual entropy (or increasing mutual information), and for a time that is not too long—the correlations (mutual information) between particles only increase with time. Therefore, the thermodynamic entropy, which is proportional to the marginal entropy, must also increase with time [6] (note that "not too long" in this context is relative to the time needed, in a classical version of the system, for it to pass through all its possible microstates—a time that can be roughly estimated as

, where

, where  is the time between particle collisions and S is the system's entropy.

In any practical case this time is huge compared to everything else).

Note that the correlation between particles is not a fully objective

quantity. One cannot measure the mutual entropy, one can only measure

its change, assuming one can measure a microstate. Thermodynamics is

restricted to the case where microstates cannot be distinguished, which

means that only the marginal entropy, proportional to the thermodynamic

entropy, can be measured, and, in a practical sense, always increases.

is the time between particle collisions and S is the system's entropy.

In any practical case this time is huge compared to everything else).

Note that the correlation between particles is not a fully objective

quantity. One cannot measure the mutual entropy, one can only measure

its change, assuming one can measure a microstate. Thermodynamics is

restricted to the case where microstates cannot be distinguished, which

means that only the marginal entropy, proportional to the thermodynamic

entropy, can be measured, and, in a practical sense, always increases.The arrow of time in various phenomena

All phenomena that behave differently in one time direction can ultimately be linked to the Second Law of Thermodynamics. This includes the fact that ice cubes melt in hot coffee rather than assembling themselves out of the coffee, that a block sliding on a rough surface slows down rather than speeding up, and that we can remember the past rather than the future. This last phenomenon, called the "psychological arrow of time", has deep connections with Maxwell's demon and the physics of information; In fact, it is easy to understand its link to the Second Law of Thermodynamics if one views memory as correlation between brain cells (or computer bits) and the outer world. Since the Second Law of Thermodynamics is equivalent to the growth with time of such correlations, then it states that memory is created as we move towards the future (rather than towards the past).Current research

Current research focuses mainly on describing the thermodynamic arrow of time mathematically, either in classical or quantum systems, and on understanding its origin from the point of view of cosmological boundary conditions.Dynamical systems

Some current research in dynamical systems indicates a possible "explanation" for the arrow of time.[citation needed] There are several ways to describe the time evolution of a dynamical system. In the classical framework, one considers a differential equation, where one of the parameters is explicitly time. By the very nature of differential equations, the solutions to such systems are inherently time-reversible. However, many of the interesting cases are either ergodic or mixing, and it is strongly suspected that mixing and ergodicity somehow underlie the fundamental mechanism of the arrow of time.Mixing and ergodic systems do not have exact solutions, and thus proving time irreversibility in a mathematical sense is (as of 2006) impossible. Some progress can be made by studying discrete-time models or difference equations. Many discrete-time models, such as the iterated functions considered in popular fractal-drawing programs, are explicitly not time-reversible, as any given point "in the present" may have several different "pasts" associated with it: indeed, the set of all pasts is known as the Julia set. Since such systems have a built-in irreversibility, it is inappropriate to use them to explain why time is not reversible.

There are other systems that are chaotic, and are also explicitly time-reversible: among these is the baker's map, which is also exactly solvable. An interesting avenue of study is to examine solutions to such systems not by iterating the dynamical system over time, but instead, to study the corresponding Frobenius-Perron operator or transfer operator for the system. For some of these systems, it can be explicitly, mathematically shown that the transfer operators are not trace-class. This means that these operators do not have a unique eigenvalue spectrum that is independent of the choice of basis. In the case of the baker's map, it can be shown that several unique and inequivalent diagonalizations or bases exist, each with a different set of eigenvalues. It is this phenomenon that can be offered as an "explanation" for the arrow of time. That is, although the iterated, discrete-time system is explicitly time-symmetric, the transfer operator is not. Furthermore, the transfer operator can be diagonalized in one of two inequivalent ways: one that describes the forward-time evolution of the system, and one that describes the backwards-time evolution.

As of 2006, this type of time-symmetry breaking has been demonstrated for only a very small number of exactly-solvable, discrete-time systems. The transfer operator for more complex systems has not been consistently formulated, and its precise definition is mired in a variety of subtle difficulties. In particular, it has not been shown that it has a broken symmetry for the simplest exactly-solvable continuous-time ergodic systems, such as Hadamard's billiards, or the Anosov flow on the tangent space of PSL(2,R).

Quantum mechanics

Research on irreversibility in quantum mechanics takes several different directions. One avenue is the study of rigged Hilbert spaces, and in particular, how discrete and continuous eigenvalue spectra intermingle[citation needed]. For example, the rational numbers are completely intermingled with the real numbers, and yet have a unique, distinct set of properties. It is hoped that the study of Hilbert spaces with a similar inter-mingling will provide insight into the arrow of time.Another distinct approach is through the study of quantum chaos by which attempts are made to quantize systems as classically chaotic, ergodic or mixing.[citation needed] The results obtained are not dissimilar from those that come from the transfer operator method. For example, the quantization of the Boltzmann gas, that is, a gas of hard (elastic) point particles in a rectangular box reveals that the eigenfunctions are space-filling fractals that occupy the entire box, and that the energy eigenvalues are very closely spaced and have an "almost continuous" spectrum (for a finite number of particles in a box, the spectrum must be, of necessity, discrete). If the initial conditions are such that all of the particles are confined to one side of the box, the system very quickly evolves into one where the particles fill the entire box. Even when all of the particles are initially on one side of the box, their wave functions do, in fact, permeate the entire box: they constructively interfere on one side, and destructively interfere on the other. Irreversibility is then argued by noting that it is "nearly impossible" for the wave functions to be "accidentally" arranged in some unlikely state: such arrangements are a set of zero measure. Because the eigenfunctions are fractals, much of the language and machinery of entropy and statistical mechanics can be imported to discuss and argue the quantum case.[citation needed]

Cosmology

Some processes that involve high energy particles and are governed by the weak force (such as K-meson decay) defy the symmetry between time directions. However, all known physical processes do preserve a more complicated symmetry (CPT symmetry), and are therefore unrelated to the second law of thermodynamics, or to our day-to-day experience of the arrow of time. A notable exception is the wave function collapse in quantum mechanics, which is an irreversible process. It has been conjectured that the collapse of the wave function may be the reason for the Second Law of Thermodynamics. However it is more accepted today that the opposite is correct, namely that the (possibly merely apparent) wave function collapse is a consequence of quantum decoherence, a process that is ultimately an outcome of the Second Law of Thermodynamics.The universe was in a uniform, high density state at its very early stages, shortly after the big bang. The hot gas in the early universe was near thermodynamic equilibrium (giving rise to the horizon problem) and hence in a state of maximum entropy, given its volume. Expansion of a gas increases its entropy, however, and expansion of the universe has therefore enabled an ongoing increase in entropy. Viewed from later eras, the early universe can thus be considered to be highly ordered. The uniformity of this early near-equilibrium state has been explained by the theory of cosmic inflation.

According to this theory our universe (or, rather, its accessible part, a radius of 46 billion light years around our location) evolved from a tiny, totally uniform volume (a portion of a much bigger universe), which expanded greatly; hence it was highly ordered. Fluctuations were then created by quantum processes related to its expansion, in a manner supposed to be such that these fluctuations are uncorrelated for any practical use. This is supposed to give the desired initial conditions needed for the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

Our universe is apparently an open universe, so that its expansion will never terminate, but it is an interesting thought experiment to imagine what would have happened had our universe been closed. In such a case, its expansion would stop at a certain time in the distant future, and then begin to shrink. Moreover, a closed universe is finite. It is unclear what would happen to the Second Law of Thermodynamics in such a case. One could imagine at least three different scenarios (in fact, only the third one is plausible, since the first two require a smooth cosmic evolution, contrary to what is observed):

- A highly controversial view is that in such a case the arrow of time will reverse.[7] The quantum fluctuations—which in the meantime have evolved into galaxies and stars—will be in superposition in such a way that the whole process described above is reversed—i.e., the fluctuations are erased by destructive interference and total uniformity is achieved once again. Thus the universe ends in a big crunch, which is similar to its beginning in the big bang. Because the two are totally symmetric, and the final state is very highly ordered, entropy must decrease close to the end of the universe, so that the Second Law of Thermodynamics reverses when the universe shrinks. This can be understood as follows: in the very early universe, interactions between fluctuations created entanglement (quantum correlations) between particles spread all over the universe; during the expansion, these particles became so distant that these correlations became negligible (see quantum decoherence). At the time the expansion halts and the universe starts to shrink, such correlated particles arrive once again at contact (after circling around the universe), and the entropy starts to decrease—because highly correlated initial conditions may lead to a decrease in entropy. Another way of putting it, is that as distant particles arrive, more and more order is revealed because these particles are highly correlated with particles that arrived earlier.

- It could be that this is the crucial point where the wavefunction collapse is important: if the collapse is real, then the quantum fluctuations will not be in superposition any longer; rather they had collapsed to a particular state (a particular arrangement of galaxies and stars), thus creating a big crunch, which is very different from the big bang. Such a scenario may be viewed as adding boundary conditions (say, at the distant future) that dictate the wavefunction collapse.[8]

- The broad consensus among the scientific community today is that smooth initial conditions lead to a highly non-smooth final state, and that this is in fact the source of the thermodynamic arrow of time.[9] Highly non-smooth gravitational systems tend to collapse to black holes, so the wavefunction of the whole universe evolves from a superposition of small fluctuations to a superposition of states with many black holes in each. It may even be that it is impossible for the universe to have both a smooth beginning and a smooth ending. Note that in this scenario the energy density of the universe in the final stages of its shrinkage is much larger than in the corresponding initial stages of its expansion (there is no destructive interference, unlike in the first scenario described above), and consists of mostly black holes rather than free particles.

In the second and third scenarios, it is the difference between the initial state and the final state of the universe that is responsible for the thermodynamic arrow of time. This is independent of the cosmological arrow of time. In the second scenario, the quantum arrow of time may be seen as the deep reason for this.