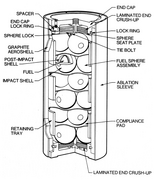

Model of the Voyager spacecraft design

|

|

| Mission type | Planetary exploration |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA / JPL[1] |

| COSPAR ID | 1977-076A[2] |

| SATCAT no. | 10271[3] |

| Website | voyager |

| Mission duration | 40 years, 9 months and 13 days elapsed Planetary mission: 12 years, 1 month, 12 days Interstellar mission: 28 years and 8 months elapsed (continuing) |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Jet Propulsion Laboratory |

| Launch mass | 825.5 kilograms (1,820 lb) |

| Power | 420 watts |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | August 20, 1977, 14:29:00 UTC |

| Rocket | Titan IIIE |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral LC-41 |

| Flyby of Jupiter | |

| Closest approach | July 9, 1979, 22:29:00 UTC |

| Distance | 570,000 kilometers (350,000 mi) |

| Flyby of Saturn | |

| Closest approach | August 25, 1981, 03:24:05 UTC |

| Distance | 101,000 km (63,000 mi) |

| Flyby of Uranus | |

| Closest approach | January 24, 1986, 17:59:47 UTC |

| Distance | 81,500 km (50,600 mi) |

| Flyby of Neptune | |

| Closest approach | August 25, 1989, 03:56:36 UTC |

| Distance | 4,951 km (3,076 mi) |

Voyager 2 is a space probe launched by NASA on August 20, 1977, to study the outer planets. Part of the Voyager program, it was launched 16 days before its twin, Voyager 1, on a trajectory that took longer to reach Jupiter and Saturn but enabled further encounters with Uranus and Neptune.[4] It is the only spacecraft to have visited either of the ice giants.

Its primary mission ended with the exploration of the Neptunian system on October 2, 1989, after having visited the Uranian system in 1986, the Saturnian system in 1981, and the Jovian system in 1979. Voyager 2 is now in its extended mission to study the outer reaches of the Solar System and has been operating for 40 years, 9 months and 13 days as of June 2, 2018. It remains in contact through the Deep Space Network.[5]

At a distance of 117 AU (1.75×1010 km) from the Sun as of March 17, 2018,[6] Voyager 2 is the fourth of five spacecraft to achieve the escape velocity that will allow them to leave the Solar System. The probe was moving at a velocity of 15.4 km/s (55,000 km/h) relative to the Sun as of December 2014 and is traveling through the heliosheath.[6][7] Upon reaching interstellar space, Voyager 2 is expected to provide the first direct measurements of the density and temperature of the interstellar plasma.[8]

Mission History

History

In the early space age, it was realized that a coincidental alignment of the outer planets would occur in the late 1970s and enable a single probe to visit Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune by taking advantage of the then-new technique of gravity assists. NASA began work on a Grand Tour, which evolved into a massive project involving two groups of two probes each, with one group visiting Jupiter, Saturn, and Pluto and the other Jupiter, Uranus, and Neptune. The spacecraft would be designed with redundant systems to ensure survival through the entire tour. By 1972 the mission was scaled back and replaced with two Mariner-derived spacecraft, the Mariner Jupiter-Saturn probes. To keep apparent lifetime program costs low, the mission would include only flybys of Jupiter and Saturn, but keep the Grand Tour option open.[4]:263 As the program progressed, the name was changed to Voyager.[9]The primary mission of Voyager 1 was to explore Jupiter, Saturn, and Saturn's moon, Titan. Voyager 2 was also to explore Jupiter and Saturn, but on a trajectory that would have option of continuing on to Uranus and Neptune, or being redirected to Titan as a backup for Voyager 1. Upon successful completion of Voyager 1's objectives, Voyager 2 would get a mission extension to send the probe on towards Uranus and Neptune.[4]

Spacecraft design

Constructed by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), Voyager 2 included 16 hydrazine thrusters, three-axis stabilization, gyroscopes and celestial referencing instruments (Sun sensor/Canopus Star Tracker) to maintain pointing of the high-gain antenna toward Earth. Collectively these instruments are part of the Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem (AACS) along with redundant units of most instruments and 8 backup thrusters. The spacecraft also included 11 scientific instruments to study celestial objects as it traveled through space.[10]Communications

Built with the intent for eventual interstellar travel, Voyager 2 included a large, 3.7 m (12 ft) parabolic, high-gain antenna (see diagram) to transceive data via the Deep Space Network on the Earth. Communications are conducted over the S-band (about 13 cm wavelength) and X-band (about 3.6 cm wavelength) providing data rates as high as 115.2 kilobits per second at the distance of Jupiter, and then ever-decreasing as the distance increased, because of the inverse-square law. When the spacecraft is unable to communicate with Earth, the Digital Tape Recorder (DTR) can record about 64 kilobytes of data for transmission at another time.[11]Power

The spacecraft was equipped with 3 Multihundred-Watt radioisotope thermoelectric generators (MHW RTG). Each RTG includes 24 pressed plutonium oxide spheres, and provided enough heat to generate approximately 157 W of electrical power at launch. Collectively, the RTGs supplied the spacecraft with 470 watts at launch, and will allow operations to continue until at least 2020.[10][12][13]

Images of the spacecraft

Voyager spacecraft diagram.

Voyager 2 awaiting payload entry into a Titan IIIE/Centaur rocket.

Mission profile

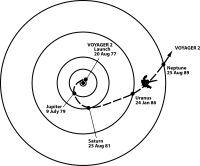

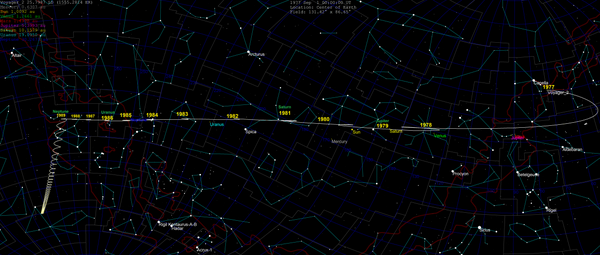

Voyager 2's trajectory from the earth, following the ecliptic through 1989 at Neptune and now heading south into the constellation Pavo |

| Timeline of travel | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

|

|||

| 1981-06-05 | Start Saturn observation phase.

|

|

|||

| 1985-11-04 | Start Uranus observation phase.

|

|

|||

| 1987-08-20 | 10 years of continuous flight and operation at 14:29:00 UTC. | ||

| 1989-06-05 | Start Neptune observation phase.

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||

Launch and trajectory

The Voyager 2 probe was launched on August 20, 1977, by NASA from Space Launch Complex 41 at Cape Canaveral, Florida, aboard a Titan IIIE/Centaur launch vehicle. Two weeks later, the twin Voyager 1 probe would be launched on September 5, 1977. However, Voyager 1 would reach both Jupiter and Saturn sooner, as Voyager 2 had been launched into a longer, more circular trajectory.-

Voyager 2 launch on August 20, 1977 with a Titan IIIE/Centaur.

-

Plot of Voyager 2's heliocentric velocity against its distance from the Sun, illustrating the use of gravity assists to accelerate the spacecraft by Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus. To observe Triton, Voyager 2 passed over Neptune's north pole, resulting in an acceleration out of the plane of the ecliptic, and, as a result, a reduced velocity relative to the Sun.[20]

Encounter with Jupiter

The trajectory of Voyager 2 through the Jupiter system

Voyager 2's closest approach to Jupiter occurred on July 9, 1979. It came within 570,000 km (350,000 mi) of the planet's cloud tops.[21] It discovered a few rings around Jupiter, as well as volcanic activity on the moon Io.

The Great Red Spot was revealed as a complex storm moving in a counterclockwise direction. An array of other smaller storms and eddies were found throughout the banded clouds.

Discovery of active volcanism on Io was easily the greatest unexpected discovery at Jupiter. It was the first time active volcanoes had been seen on another body in the Solar System. Together, the Voyagers observed the eruption of nine volcanoes on Io, and there is evidence that other eruptions occurred between the two Voyager fly-bys.

The moon Europa displayed a large number of intersecting linear features in the low-resolution photos from Voyager 1. At first, scientists believed the features might be deep cracks, caused by crustal rifting or tectonic processes. The closer high-resolution photos from Voyager 2, however, left scientists puzzled: The features were so lacking in topographic relief that as one scientist described them, they "might have been painted on with a felt marker." Europa is internally active due to tidal heating at a level about one-tenth that of Io. Europa is thought to have a thin crust (less than 30 km (19 mi) thick) of water ice, possibly floating on a 50-kilometer-deep (30 mile) ocean.

Two new, small satellites, Adrastea and Metis, were found orbiting just outside the ring. A third new satellite, Thebe, was discovered between the orbits of Amalthea and Io.

A color mosaic of Ganymede.

Callisto photographed at a distance of 1 million kilometers.

One faint ring of Jupiter photographed during the flyby.

Atmospheric eruptive event on Jupiter.

Encounter with Saturn

The closest approach to Saturn occurred on August 26, 1981.[22]While passing behind Saturn (as viewed from Earth), Voyager 2 probed Saturn's upper atmosphere with its radio link to gather information on atmospheric temperature and density profiles. Voyager 2 found that at the uppermost pressure levels (seven kilopascals of pressure), Saturn's temperature was 70 kelvins (−203 °C), while at the deepest levels measured (120 kilopascals) the temperature increased to 143 K (−130 °C). The north pole was found to be 10 kelvins cooler, although this may be seasonal (see also Saturn Oppositions).

After the fly-by of Saturn, the camera platform of Voyager 2 locked up briefly, putting plans to officially extend the mission to Uranus and Neptune in jeopardy. The mission's engineers were able to fix the problem (caused by an overuse that temporarily depleted its lubricant), and the Voyager 2 probe was given the go-ahead to explore the Uranian system.

Atmosphere of Titan imaged from 2.3 million km.

Titan occultation of the Sun from 0.9 million km.

Two-toned Iapetus, August 22, 1981.

"Spoke" features observed in the rings of Saturn.

Encounter with Uranus

The closest approach to Uranus occurred on January 24, 1986, when Voyager 2 came within 81,500 kilometers (50,600 mi) of the planet's cloud tops. Voyager 2 also discovered the moons Cordelia, Ophelia, Bianca, Cressida, Desdemona, Juliet, Portia, Rosalind, Belinda, Perdita and Puck; studied the planet's unique atmosphere, caused by its axial tilt of 97.8°; and examined the Uranian ring system.

Uranus is the third largest (Neptune has a larger mass, but a smaller volume) planet in the Solar System. It orbits the Sun at a distance of about 2.8 billion kilometers (1.7 billion miles), and it completes one orbit every 84 Earth years. The length of a day on Uranus as measured by Voyager 2 is 17 hours, 14 minutes. Uranus is unique among the planets in that its axial tilt is about 90°, meaning that its axis is roughly parallel with, not perpendicular to, the plane of the ecliptic. This extremely large tilt of its axis is thought to be the result of a collision between the accumulating planet Uranus with another planet-sized body early in the history of the Solar System. Given the unusual orientation of its axis, with the polar regions of Uranus exposed for periods of many years to either continuous sunlight or darkness, planetary scientists were not at all sure what to expect when observing Uranus.

Voyager 2 found that one of the most striking effects of the sideways orientation of Uranus is the effect on the tail of the planetary magnetic field. This is itself tilted about 60° from the Uranian axis of rotation. The planet's magneto tail was shown to be twisted by the rotation of Uranus into a long corkscrew shape following the planet. The presence of a significant magnetic field for Uranus was not at all known until Voyager 2's arrival.

The radiation belts of Uranus were found to be of an intensity similar to those of Saturn. The intensity of radiation within the Uranian belts is such that irradiation would "quickly" darken — within 100,000 years — any methane that is trapped in the icy surfaces of the inner moons and ring particles. This kind of darkening might have contributed to the darkened surfaces of the moons and the ring particles, which are almost uniformly dark gray in color.

A high layer of haze was detected around the sunlit pole of Uranus. This area was also found to radiate large amounts of ultraviolet light, a phenomenon that is called "dayglow." The average atmospheric temperature is about 60 K (−350°F/−213°C). Surprisingly, the illuminated and dark poles, and most of the planet, exhibit nearly the same temperatures at the cloud tops.

The Uranian moon Miranda, the innermost of the five large moons, was discovered to be one of the strangest bodies yet seen in the Solar System. Detailed images from Voyager 2's flyby of Miranda showed huge canyons made from geological faults as deep as 20 kilometers (12 mi), terraced layers, and a mixture of old and young surfaces. One hypothesis suggests that Miranda might consist of a reaggregation of material following an earlier event when Miranda was shattered into pieces by a violent impact.

All nine of the previously known Uranian rings were studied by the instruments of Voyager 2. These measurements showed that the Uranian rings are distinctly different from those at Jupiter and Saturn. The Uranian ring system might be relatively young, and it did not form at the same time that Uranus did. The particles that make up the rings might be the remnants of a moon that was broken up by either a high-velocity impact or torn up by tidal effects.

Color composite of Titania from 500,000 km.

Umbriel (moon) imaged from 550,000 km.

Oberon (computer generated image).

The Rings of Uranus imaged by Voyager 2.

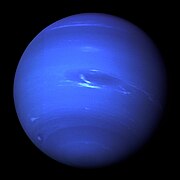

Encounter with Neptune

Following a mid-course correction in 1987, Voyager 2's closest approach to Neptune occurred on August 25, 1989.[23][24][25] Because this was the last planet of the Solar System that Voyager 2 could visit, the Chief Project Scientist, his staff members, and the flight controllers decided to also perform a close fly-by of Triton, the larger of Neptune's two originally known moons, so as to gather as much information on Neptune and Triton as possible, regardless of Voyager 2's departure angle from the planet. This was just like the case of Voyager 1's encounters with Saturn and its massive moon Titan.Through repeated computerized test simulations of trajectories through the Neptunian system conducted in advance, flight controllers determined the best way to route Voyager 2 through the Neptune-Triton system. Since the plane of the orbit of Triton is tilted significantly with respect to the plane of the ecliptic, through mid-course corrections, Voyager 2 was directed into a path about three thousand miles above the north pole of Neptune.[26] At that time, Triton was behind and below (south of) Neptune (at an angle of about 25 degrees below the ecliptic), close to the apoapsis of its elliptical orbit. The gravitational pull of Neptune bent the trajectory of Voyager 2 down in the direction of Triton. In less than 24 hours, Voyager 2 traversed the distance between Neptune and Triton, and then observed Triton's northern hemisphere as it passed over its north pole.The net and final effect on Voyager 2 was to bend its trajectory south below the plane of the ecliptic by about 30 degrees. Voyager 2 is on this path permanently, and hence, it is exploring space south of the plane of the ecliptic, measuring magnetic fields, charged particles, etc., there, and sending the measurements back to the Earth via telemetry.

While in the neighborhood of Neptune, Voyager 2 discovered the "Great Dark Spot", which has since disappeared, according to observations by the Hubble Space Telescope. Originally thought to be a large cloud itself, the "Great Dark Spot" was later hypothesized to be a hole in the visible cloud deck of Neptune.

With the decision of the International Astronomical Union to reclassify Pluto as a "dwarf planet" in 2006, the flyby of Neptune by Voyager 2 in 1989 became the point when every known planet in the Solar System had been visited at least once by a space probe.

Interstellar mission

Once its planetary mission was over, Voyager 2 was described as working on an interstellar mission, which NASA is using to find out what the Solar System is like beyond the heliosphere. Voyager 2 is currently transmitting scientific data at about 160 bits per second. Information about continuing telemetry exchanges with Voyager 2 is available from Voyager Weekly Reports.[27]

Map showing location and trajectories of the Pioneer 10, Pioneer 11, Voyager 1, and Voyager 2 spacecraft, as of April 4, 2007.

On November 29, 2006, a telemetered command to Voyager 2 was incorrectly decoded by its on-board computer—in a random error—as a command to turn on the electrical heaters of the spacecraft's magnetometer. These heaters remained turned on until December 4, 2006, and during that time, there was a resulting high temperature above 130 °C (266 °F), significantly higher than the magnetometers were designed to endure, and a sensor rotated away from the correct orientation. As of this date it had not been possible to fully diagnose and correct for the damage caused to Voyager 2's magnetometer, although efforts to do so were proceeding.[28]

On August 30, 2007, Voyager 2 passed the termination shock and then entered into the heliosheath, approximately 1 billion miles (1.6 billion km) closer to the Sun than Voyager 1 did.[29] This is due to the interstellar magnetic field of deep space. The southern hemisphere of the Solar System's heliosphere is being pushed in.[30]

On April 22, 2010, Voyager 2 encountered scientific data format problems.[31] On May 17, 2010, JPL engineers revealed that a flipped bit in an on-board computer had caused the issue, and scheduled a bit reset for May 19.[32] On May 23, 2010, Voyager 2 resumed sending science data from deep space after engineers fixed the flipped bit.[33] Currently research is being made into marking the area of memory with the flipped bit off limits or disallowing its use. The Low-Energy Charged Particle Instrument is currently operational, and data from this instrument concerning charged particles is being transmitted to Earth. This data permits measurements of the heliosheath and termination shock. There has also been a modification to the on-board flight software to delay turning off the AP Branch 2 backup heater for one year. It was scheduled to go off February 2, 2011 (DOY 033, 2011–033).

Simulated view of the position of Voyager 2 as of February 8, 2012 showing spacecraft trajectory since launch

On July 25, 2012, Voyager 2 was traveling at 15.447 km/s relative to the Sun at about 99.13 astronomical units (1.4830×1010 km) from the Sun,[6] at −55.29° declination and 19.888 h right ascension, and also at an ecliptic latitude of −34.0 degrees, placing it in the constellation Telescopium as observed from Earth.[34] This location places it deep in the scattered disc, and traveling outward at roughly 3.264 AU per year. It is more than twice as far from the Sun as Pluto, and far beyond the perihelion of 90377 Sedna, but not yet beyond the outer limits of the orbit of the dwarf planet Eris.

On September 9, 2012, Voyager 2 was 99.077 AU (1.48217×1010 km; 9.2098×109 mi) from the Earth and 99.504 AU (1.48856×1010 km; 9.2495×109 mi) from the Sun; and traveling at 15.436 km/s (34,530 mph) (relative to the Sun) and traveling outward at about 3.256 AU per year.[35] Sunlight takes 13.73 hours to get to Voyager 2. The brightness of the Sun from the spacecraft is magnitude -16.7.[35] Voyager 2 is heading in the direction of the constellation Telescopium.[35] (To compare, Proxima Centauri, the closest star to the Sun, is about 4.2 light-years (or 2.65×105 AU) distant. Voyager 2's current relative velocity to the Sun is 15.436 km/s (55,570 km/h; 34,530 mph). This calculates as 3.254 AU per year, about 10% slower than Voyager 1. At this velocity, 81,438 years would pass before Voyager 2 reaches the nearest star, Proxima Centauri, were the spacecraft traveling in the direction of that star. (Voyager 2 will need about 19,390 years at its current velocity to travel a complete light year)

On November 7, 2012, Voyager 2 reached 100 AU from the sun, making it the third human-made object to reach 100 AU. Voyager 1 was 122 AU from the Sun, and Pioneer 10 is presumed to be at 107 AU. While Pioneer has ceased communications, both the Voyager spacecraft are performing well and are still communicating.

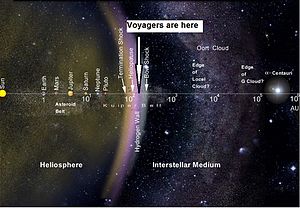

The current position of Voyagers as of early 2013. Note the vast

distances condensed into an exponential scale: Earth is 1 astronomical

unit (AU) from the Sun; Saturn is at 9 AU, and the heliopause is at more

than 100 AU. Neptune is 30.1 AU from the Sun; thus the edge of

interstellar space is more than three times as far from the Sun as the

last planet.

In 2013 Voyager 1 was escaping the solar system at a speed of about 3.6 AU per year, while Voyager 2 was only escaping at 3.3 AU per year.[36] (Each year Voyager 1 increases its lead over Voyager 2)

By March 17, 2018, Voyager 2 was at a distance of 117 AU (1.75×1010 km) from the Sun.[6] There is a variation in distance from Earth caused by the Earth's revolution around the Sun relative to Voyager 2.[6]

Future of the probe

It was originally thought that Voyager 2 would enter interstellar space in early 2016, with its plasma spectrometer providing the first direct measurements of the density and temperature of the interstellar plasma.[37]However, the spacecraft may instead reach interstellar space sometime in either late 2019 or early 2020, when it will reach a similar distance from the Sun as Voyager 1 did when it crossed into interstellar space back in 2012. Voyager 2 is not headed toward any particular star, although in roughly 40,000 years it should pass 1.7 light-years from the star Ross 248.[38] And if undisturbed for 296,000 years, Voyager 2 should pass by the star Sirius at a distance of 4.3 light-years. Voyager 2 is expected to keep transmitting weak radio messages until at least 2025, over 48 years after it was launched.[39]

| Year | End of specific capabilities as a result of the available electrical power limitations[40] |

|---|---|

| 1998 | Termination of scan platform and UVS observations |

| 2007 | Termination of Digital Tape Recorder (DTR) operations (It was no longer needed due to a failure on the High Waveform Receiver on the Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS) on June 30, 2002.[41]) |

| 2008 | Power off Planetary Radio Astronomy Experiment (PRA) |

| 2016 approx | Termination of gyroscopic operations |

| 2020 approx | Initiate instrument power sharing |

| 2025 or slightly afterwards | Can no longer power any single instrument |

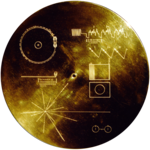

Golden record

A child's greeting in English recorded on the Voyager Golden Record

Voyager Golden Record