Eris (center) and Dysnomia (left of center), taken by the Hubble Space Telescope

|

|||||||||

| Discovery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discovered by | |||||||||

| Discovery date | January 5, 2005[2][a] | ||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||

| MPC designation | (136199) Eris | ||||||||

| Pronunciation | /ˈɪərɪs/ or /ˈɛrɪs/[b] | ||||||||

Named after

|

Eris | ||||||||

| 2003 UB313[3] | |||||||||

| Adjectives | Eridian | ||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[3] | |||||||||

| Epoch December 9, 2014 (JD 2457000.5) |

|||||||||

| Earliest precovery date | September 3, 1954 | ||||||||

| Aphelion |

|

||||||||

| Perihelion |

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.44068 | ||||||||

|

|||||||||

Average orbital speed

|

3.4338 km/s | ||||||||

| 204.16° | |||||||||

| Inclination | 44.0445° | ||||||||

| 35.9531° | |||||||||

| 150.977° | |||||||||

| Known satellites | Dysnomia | ||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||

| Dimensions | 2326±12 km | ||||||||

Mean radius

|

1163±6 km[8][9] | ||||||||

| (1.70±0.02)×107 km2[c] | |||||||||

| Volume | (6.59±0.10)×109 km3[c] | ||||||||

| Mass | |||||||||

Mean density

|

2.52±0.07 g/cm3[d] | ||||||||

Equatorial surface gravity

|

0.82±0.02 m/s2 0.083±0.002 g[e] |

||||||||

Equatorial escape velocity

|

1.38±0.01 km/s[e] | ||||||||

Sidereal rotation period

|

25.9±0.5 hr[11] | ||||||||

| 0.96+0.09 −0.04[8] |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

| B−V=0.78, V−R=0.45[12] | |||||||||

| 18.7[13] | |||||||||

| −1.17+0.06 −0.11[f] |

|||||||||

| 40 milli-arcsec[15] | |||||||||

Eris (minor-planet designation 136199 Eris) is the most massive and second-largest (by volume) dwarf planet in the known Solar System. Eris was discovered in January 2005 by a Palomar Observatory-based team led by Mike Brown, and its identity was verified later that year. In September 2006 it was named after Eris, the Greek goddess of strife and discord. Eris is the ninth most massive object directly orbiting the Sun, and the 16th most massive overall, because seven moons are more massive than all known dwarf planets. It is also the largest which has not yet been visited by a spacecraft. Eris was measured to be 2,326 ± 12 kilometers (1,445.3 ± 7.5 mi) in diameter.[8] Eris's mass is about 0.27% of the Earth mass,[10][16] about 27% more than dwarf planet Pluto, although Pluto is slightly larger by volume.[17]

Eris is a trans-Neptunian object (TNO) and a member of a high-eccentricity population known as the scattered disk. It has one known moon, Dysnomia. As of February 2016, its distance from the Sun was 96.3 astronomical units (1.441×1010 km; 8.95×109 mi),[13] roughly three times that of Pluto. With the exception of some long-period comets, Eris and Dysnomia are currently the most distant known natural objects in the Solar System.[18][g]

Because Eris appeared to be larger than Pluto, NASA initially described it as the Solar System's tenth planet. This, along with the prospect of other objects of similar size being discovered in the future, motivated the International Astronomical Union (IAU) to define the term planet for the first time. Under the IAU definition approved on August 24, 2006, Eris is a "dwarf planet", along with objects such as Pluto, Ceres, Haumea and Makemake,[21] thereby reducing the number of known planets in the Solar System to eight, the same as before Pluto's discovery in 1930. Observations of a stellar occultation by Eris in 2010, showed that its diameter was 2,326 ± 12 kilometers (1,445.3 ± 7.5 mi), very slightly less than Pluto,[22][23] which was measured by New Horizons as 2,372 ± 4 kilometers (1,473.9 ± 2.5 mi) in July 2015.[24]

History

Discovery

Animation showing the movement of Eris on the images used to discover

it. Eris is indicated by the arrow. The three frames were taken over a

period of three hours.

Eris was discovered by the team of Mike Brown, Chad Trujillo, and David Rabinowitz[2] on January 5, 2005, from images taken on October 21, 2003. The discovery was announced on July 29, 2005, the same day as Makemake and two days after Haumea,[25] due in part to events that would later lead to controversy about Haumea. The search team had been systematically scanning for large outer Solar System bodies for several years, and had been involved in the discovery of several other large TNOs, including 50000 Quaoar, 90482 Orcus, and 90377 Sedna.

Routine observations were taken by the team on October 21, 2003, using the 1.2 m Samuel Oschin Schmidt telescope at Palomar Observatory, California, but the image of Eris was not discovered at that point due to its very slow motion across the sky: The team's automatic image-searching software excluded all objects moving at less than 1.5 arcseconds per hour to reduce the number of false positives returned. When Sedna was discovered, it was moving at 1.75 arcsec/h, and in light of that the team reanalyzed their old data with a lower limit on the angular motion, sorting through the previously excluded images by eye. In January 2005, the re-analysis revealed Eris's slow motion against the background stars.

Follow-up observations were then carried out to make a preliminary determination of Eris's orbit, which allowed the object's distance to be estimated. The team had planned to delay announcing their discoveries of the bright objects Eris and Makemake until further observations and calculations were complete, but announced them both on July 29 when the discovery of another large TNO they had been tracking, Haumea, was controversially announced on July 27 by a different team in Spain.[2]

Precovery images of Eris have been identified back to September 3, 1954.[3]

More observations released in October 2005 revealed that Eris has a moon, later named Dysnomia. Observations of Dysnomia's orbit permitted scientists to determine the mass of Eris, which in June 2007 they calculated to be (1.66±0.02)×1022 kg,[10] 27%±2% greater than Pluto's.

Name

Eris is named after the Greek goddess Eris (Greek Ἔρις), a personification of strife and discord.[26] The name was proposed by the CalTech Team on September 6, 2006, and it was assigned on September 13, 2006,[27] following an unusually long period in which the object was known by the provisional designation 2003 UB313, which was granted automatically by the IAU under their naming protocols for minor planets. The regular adjectival form of Eris is Eridian.

Xena

Due to uncertainty over whether the object would be classified as a planet or a minor planet, because different nomenclature procedures apply to these different classes of objects,[28] the decision on what to name the object had to wait until after the August 24, 2006, IAU ruling.[29] As a result, for a time the object became known to the wider public as Xena."Xena" was an informal name used internally by the discovery team. It was inspired by the title character of the television series Xena: Warrior Princess. The discovery team had reportedly saved the nickname "Xena" for the first body they discovered that was larger than Pluto. According to Brown,

We chose it since it started with an X (planet "X"), it sounds mythological (OK, so it's TV mythology, but Pluto is named after a cartoon, right?),[h] and (this part is actually true) we've been working to get more female deities out there (e.g. Sedna). Also, at the time, the TV show was still on TV, which shows you how long we've been searching![31]"We assumed [that] a real name would come out fairly quickly, [but] the process got stalled", Mike Brown said in interview,

One reporter [Ken Chang][32] called me up from the New York Times who happened to have been a friend of mine from college, [and] I was a little less guarded with him than I am with the normal press. He asked me, "What's the name you guys proposed?" and I said, "Well, I'm not going to tell." And he said, "Well, what do you guys call it when you're just talking amongst yourselves?"... As far as I remember this was the only time I told anybody this in the press, and then it got everywhere, which I only sorta felt bad about—I kinda like the name.[33]

Choosing an official name

According to science writer Govert Schilling, Brown initially wanted to call the object "Lila", after a concept in Hindu mythology that described the cosmos as the outcome of a game played by Brahman. The name was very similar to "Lilah", the name of Brown's newborn daughter. Brown was mindful of not making his name public before it had been officially accepted. He had done so with Sedna a year previously, and had been heavily criticized. However, no objection was raised to the Sedna name other than the breach of protocol, and no competing names were suggested for Sedna.[35]

He listed the address of his personal web page announcing the discovery as /~mbrown/planetlila and in the chaos following the controversy over the discovery of Haumea, forgot to change it. Rather than needlessly anger more of his fellow astronomers, he simply said that the webpage had been named for his daughter and dropped "Lila" from consideration.[36]

Brown had also speculated that Persephone, the wife of the god Pluto, would be a good name for the object.[2] The name had been used several times in science fiction,[37] and was popular with the public, having handily won a poll conducted by New Scientist magazine ("Xena", despite only being a nickname, came fourth).[38] This was not possible once the object was classified as a dwarf planet, because there is already an asteroid with that name, 399 Persephone.[2]

With the dispute resolved, the discovery team proposed Eris on September 6, 2006. On September 13, 2006 this name was accepted as the official name by the IAU.[39][40] Brown decided that, because the object had been considered a planet for so long, it deserved a name from Greek or Roman mythology, like the other planets. The asteroids had taken the vast majority of Graeco-Roman names. Eris, whom Brown described as his favorite goddess, had fortunately escaped inclusion.[33] The name in part reflects the discord in the astronomical community caused by the debate over the object's (and Pluto's) classification.

Classification

Distribution of trans-Neptunian objects

Eris is a trans-Neptunian dwarf planet (plutoid).[41] Its orbital characteristics more specifically categorize it as a scattered-disk object (SDO), or a TNO that has been "scattered" from the Kuiper belt into more-distant and unusual orbits following gravitational interactions with Neptune as the Solar System was forming. Although its high orbital inclination is unusual among the known SDOs, theoretical models suggest that objects that were originally near the inner edge of the Kuiper belt were scattered into orbits with higher inclinations than objects from the outer belt.[42] Inner-belt objects are expected to be generally more massive than outer-belt objects, and so astronomers expect to discover more large objects like Eris in high-inclination orbits, which planetary searches have traditionally neglected.

Because Eris was initially thought to be larger than Pluto, it was described as the "tenth planet" by NASA and in media reports of its discovery.[43] In response to the uncertainty over its status, and because of ongoing debate over whether Pluto should be classified as a planet, the IAU delegated a group of astronomers to develop a sufficiently precise definition of the term planet to decide the issue. This was announced as the IAU's Definition of a Planet in the Solar System, adopted on 24 August 2006. At this time, both Eris and Pluto were classified as dwarf planets, a category distinct from the new definition of planet.[44] Brown has since stated his approval of this classification.[45] The IAU subsequently added Eris to its Minor Planet Catalogue, designating it (136199) Eris.[29]

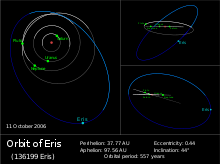

Orbit

Seen from earth, Eris makes small loops in the sky through the constellation of Cetus

Eris has an orbital period of 558 years.[13] Its maximum possible distance from the Sun (aphelion) is 97.65 AU, and its closest (perihelion) is 37.91 AU.[13] It came to perihelion between 1698[5] and 1699,[46] to aphelion around 1977,[46] and will return to perihelion around 2256[46] to 2258.[11] Eris and its moon are currently the most distant known objects in the Solar System, apart from long-period comets and space probes.[2][47] Approximately forty known TNOs, most notably 2006 SQ372, 2000 OO67 and Sedna, though currently closer to the Sun than Eris, have greater average orbital distances than Eris's semimajor axis of 67.7 AU.[4]

Eris's orbit is highly eccentric, and brings Eris to within 37.9 AU of the Sun, a typical perihelion for scattered objects. This is within the orbit of Pluto, but still safe from direct interaction with Neptune (29.8–30.4 AU). Pluto, on the other hand, like other plutinos, follows a less inclined and less eccentric orbit and, protected by orbital resonance, can cross Neptune's orbit. It is possible that Eris is in a 17:5 resonance with Neptune, though further observations will be required to check that hypothesis.[48] Unlike the eight planets, whose orbits all lie roughly in the same plane as the Earth's, Eris's orbit is highly inclined: It is tilted at an angle of about 44 degrees to the ecliptic. In about 800 years, Eris will be closer to the Sun than Pluto for some time (see the graph at the right).

The distances of Eris and Pluto from the Sun in the next 1,000 years

As of February 2016, Eris has an apparent magnitude of 18.7, making it bright enough to be detectable to some amateur telescopes. A 200-millimeter (7.9 in) telescope with a CCD can detect Eris under favorable conditions.[i] The reason it had not been noticed until now is its steep orbital inclination; searches for large outer Solar System objects tend to concentrate on the ecliptic plane, where most bodies are found.

Because of the high inclination of its orbit, Eris only passes through a few constellations of the traditional Zodiac; it is now in the constellation Cetus. It was in Sculptor from 1876 until 1929 and Phoenix from roughly 1840 until 1875. In 2036 it will enter Pisces and stay there until 2065, when it will enter Aries.[46] It will then move into the northern sky, entering Perseus in 2128 and Camelopardalis (where it will reach its northernmost declination) in 2173.

Size, mass and density

| Year | Radius (diameter) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 1,199 (2,397) km[50] | Hubble |

| 2007 | 1,300 (2,600) km[51] | Spitzer |

| 2011 | 1,163 (2,326) km[8] | Occultation |

In 2005, the diameter of Eris was measured to be 2397±100 km, using images from the Hubble Space Telescope (HST).[50][52] The size of an object is determined from its absolute magnitude (H) and the albedo (the amount of light it reflects). At a distance of 97 AU, an object with a diameter of 3,000 km would have an angular size of 40 milliarcseconds,[15] which is directly measurable with the Hubble Space Telescope. Although resolving such small objects is at the very limit of its capabilities,[j] sophisticated image processing techniques such as deconvolution can be used to measure such angular sizes fairly accurately.[k]

Artistic comparison of Pluto, Eris, Makemake, Haumea, Sedna, 2002 MS4, 2007 OR10, Quaoar, Salacia, Orcus, and Earth along with the Moon.

This makes Eris around the same size as Pluto, which is 2372±4 km across. It also indicates an albedo of 0.96, higher than that of any other large body in the Solar System except Enceladus.[8]

It is speculated that the high albedo is due to the surface ices being

replenished because of temperature fluctuations as Eris's eccentric

orbit takes it closer and farther from the Sun.[54]

In 2007, a series of observations of the largest trans-Neptunian objects with the Spitzer Space Telescope gave an estimate of Eris's diameter of 2600+400

−200 km.[51] The Spitzer and Hubble estimates overlap in the range of 2,400–2,500 km, 4–8% larger than Pluto. Astronomers now suspect that Eris's spin axis is currently pointing toward the Sun, which would make the sunlit hemisphere warmer than average and skew any infrared measurements toward higher values.[9] So the outcome from the 2010 Chile occultation is actually more in line with the Hubble result from 2005.[9]

In November 2010, Eris was the subject of one of the most distant stellar occultations yet from Earth.[9] Preliminary data from this event cast doubt on previous size estimates.[9] The teams announced their final results from the occultation in October 2011, with an estimated diameter of 2326+6

−6 km.[8] The mass of Eris can be calculated with much greater precision. Based on the currently accepted value for Dysnomia's period—15.774 days—[10][55] Eris is 27 percent more massive than Pluto. If the 2011 occultation results are used, then Eris has a density of 2.52±0.07 g/cm3,[d] substantially denser than Pluto, and thus must be composed largely of rocky materials.[8]

Models of internal heating via radioactive decay suggest that Eris could have an internal ocean of liquid water at the mantle–core boundary.[56]

In July 2015, after nearly ten years of Eris being considered the ninth-largest object known to directly orbit the sun, close-up imagery from the New Horizons mission more accurately determined Pluto's volume to be slightly larger than Eris's, rather than slightly smaller as previously thought. Eris is now the tenth-largest object known to directly orbit the sun by volume, though not by mass.[57]

Surface and atmosphere

The infrared spectrum of Eris, compared to that of Pluto, shows the

marked similarities between the two bodies. Arrows denote methane

absorption lines.

The discovery team followed up their initial identification of Eris with spectroscopic observations made at the 8 m Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii on January 25, 2005. Infrared light from the object revealed the presence of methane ice, indicating that the surface may be similar to that of Pluto, which at the time was the only TNO known to have surface methane, and of Neptune's moon Triton, which also has methane on its surface.[58] No surface details can be resolved from Earth or its orbit with any instrument currently available.

Due to Eris's distant eccentric orbit, its surface temperature is estimated to vary between about 30 and 56 K (−243.2 and −217.2 °C).[2]

Unlike the somewhat reddish Pluto and Triton, Eris appears almost white.[2] Pluto's reddish color is thought to be due to deposits of tholins on its surface, and where these deposits darken the surface, the lower albedo leads to higher temperatures and the evaporation of methane deposits. In contrast, Eris is far enough from the Sun that methane can condense onto its surface even where the albedo is low. The condensation of methane uniformly over the surface reduces any albedo contrasts and would cover up any deposits of red tholins.[59]

Even though Eris can be up to three times farther from the Sun than Pluto, it approaches close enough that some of the ices on the surface might warm enough to sublime. Because methane is highly volatile, its presence shows either that Eris has always resided in the distant reaches of the Solar System, where it is cold enough for methane ice to persist, or that the celestial body has an internal source of methane to replenish gas that escapes from its atmosphere. This contrasts with observations of another discovered TNO, Haumea, which reveal the presence of water ice but not methane.[60]