A protocell (or protobiont) is a self-organized, endogenously ordered, spherical collection of lipids proposed as a stepping-stone to the origin of life. A central question in evolution is how simple protocells first arose and how they could differ in reproductive output, thus enabling the accumulation of novel biological emergences over time, i.e. biological evolution. Although a functional protocell has not yet been achieved in a laboratory setting, the goal to understand the process appears well within reach.

Overview

Selectivity for compartmentalization

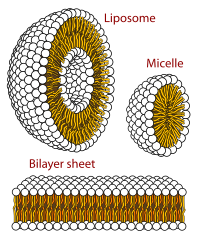

The three main structures phospholipids form in solution; the liposome (a closed bilayer), the micelle and the bilayer.

Self-assembled vesicles are essential components of primitive cells. The second law of thermodynamics requires that the universe move in a direction in which disorder (or entropy) increases, yet life is distinguished by its great degree of organization. Therefore, a boundary is needed to separate life processes from non-living matter. The cell membrane is the only cellular structure that is found in all of the cells of all of the organisms on Earth.

Researchers Irene A. Chen and Jack W. Szostak (Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2009) amongst others, demonstrated that simple physicochemical properties of elementary protocells can give rise to essential cellular behaviors, including primitive forms of Darwinian competition and energy storage. Such cooperative interactions between the membrane and encapsulated contents could greatly simplify the transition from replicating molecules to true cells. Competition for membrane molecules would favor stabilized membranes, suggesting a selective advantage for the evolution of cross-linked fatty acids and even the phospholipids of today. This micro-encapsulation allowed for metabolism within the membrane, exchange of small molecules and prevention of passage of large substances across it. The main advantages of encapsulation include increased solubility of the cargo and creating energy in the form of chemical gradient. Energy is thus often said to be stored by cells in the structures of molecules of substances such as carbohydrates (including sugars), lipids, and proteins, which release energy when chemically combined with oxygen during cellular respiration.

Energy gradient

A March 2014 study by NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory demonstrated a unique way to study the origins of life: fuel cells. Fuel cells are similar to biological cells in that electrons are also transferred to and from molecules. In both cases, this results in electricity and power. The study states that one important factor was that the Earth provides electrical energy at the seafloor. "This energy could have kick-started life and could have sustained life after it arose. Now, we have a way of testing different materials and environments that could have helped life arise not just on Earth, but possibly on Mars, Europa and other places in the Solar System."Vesicles and micelles

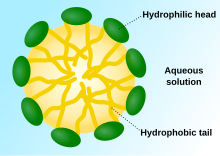

When phospholipids are placed in water, the molecules spontaneously arrange such that the tails are shielded from the water, resulting in the formation of membrane structures such as bilayers, vesicles, and micelles. In modern cells, vesicles are involved in metabolism, transport, buoyancy control, and enzyme storage. They can also act as natural chemical reaction chambers. A typical vesicle or micelle in aqueous solution forms an aggregate with the hydrophilic "head" regions in contact with surrounding solvent, sequestering the hydrophobic single-tail regions in the micelle centre. This phase is caused by the packing behavior of single-tail lipids in a bilayer. Although the protocellular self-assembly process that spontaneously form lipid monolayer vesicles and micelles in nature resemble the kinds of primordial vesicles or protocells that might have existed at the beginning of evolution, they are not as sophisticated as the bilayer membranes of today's living organisms.

Rather than being made up of phospholipids, however, early membranes may have formed from monolayers or bilayers of fatty acids, which may have formed more readily in a prebiotic environment. Fatty acids have been synthesized in laboratories under a variety of prebiotic conditions and have been found on meteorites, suggesting their natural synthesis in nature.

Oleic acid vesicles represent good models of membrane protocells that could have existed in prebiotic times.

Electrostatic interactions induced by short, positively charged, hydrophobic peptides containing 7 amino acids in length or fewer, can attach RNA to a vesicle membrane, the basic cell membrane.

Geothermal ponds and clay

This fluid lipid bilayer cross section is made up entirely of phosphatidylcholine.

Scientists have come to conclude that life began in hydrothermal vents in the deep sea, but a 2012 study suggests that inland pools of condensed and cooled geothermal vapor have the ideal characteristics for the origin of life. The conclusion is based mainly on the chemistry of modern cells, where the cytoplasm is rich in potassium, zinc, manganese, and phosphate ions, which are not widespread in marine environments. Such conditions, the researchers argue, are found only where hot hydrothermal fluid brings the ions to the surface—places such as geysers, mud pots, fumaroles and other geothermal features. Within these fuming and bubbling basins, water laden with zinc and manganese ions could have collected, cooled and condensed in shallow pools.

Another study in the 1990s showed that montmorillonite clay can help create RNA chains of as many as 50 nucleotides joined together spontaneously into a single RNA molecule. Later, in 2002, it was discovered that by adding montmorillonite to a solution of fatty acid micelles (lipid spheres), the clay sped up the rate of vesicle formation 100-fold.

Research has shown that some minerals can catalyze the stepwise formation of hydrocarbon tails of fatty acids from hydrogen and carbon monoxide gases—gases that may have been released from hydrothermal vents or geysers. Fatty acids of various lengths are eventually released into the surrounding water, but vesicle formation requires a higher concentration of fatty acids, so it is suggested that protocell formation started at land-bound hydrothermal vents such as geysers, mud pots, fumaroles and other geothermal features where water evaporates and concentrates the solute.

Montmorillonite bubbles

Another group suggests that primitive cells might have formed inside inorganic clay microcompartments, which can provide an ideal container for the synthesis and compartmentalization of complex organic molecules. Clay-armored bubbles form naturally when particles of montmorillonite clay collect on the outer surface of air bubbles under water. This creates a semi permeable vesicle from materials that are readily available in the environment. The authors remark that montmorillonite is known to serve as a chemical catalyst, encouraging lipids to form membranes and single nucleotides to join into strands of RNA. Primitive reproduction can be envisioned when the clay bubbles burst, releasing the lipid membrane-bound product into the surrounding medium.Membrane transport

Schematic

showing two possible conformations of the lipids at the edge of a pore.

In the top image the lipids have not rearranged, so the pore wall is

hydrophobic. In the bottom image some of the lipid heads have bent over,

so the pore wall is hydrophilic.

For cellular organisms, the transport of specific molecules across compartmentalizing membrane barriers is essential in order to exchange content with their environment and with other individuals. For example, content exchange between individuals enables horizontal gene transfer, an important factor in the evolution of cellular life. While modern cells can rely on complicated protein machineries to catalyze these crucial processes, protocells must have accomplished this using more simple mechanisms.

Protocells composed of fatty acids would have been able to easily exchange small molecules and ions with their environment. Membranes consisting of fatty acids have a relatively high permeability to molecules such as nucleoside monophosphate (NMP), nucleoside diphosphate (NDP), and nucleoside triphosphate (NTP), and may withstand millimolar concentrations of Mg2+. Osmotic pressure can also play a significant role regarding this passive membrane transport.

Environmental effects have been suggested to trigger conditions under which a transport of larger molecules, such as DNA and RNA, across the membranes of protocells is possible. For example, it has been proposed that electroporation resulting from lightning strikes could enable such transport. Electroporation is the rapid increase in bilayer permeability induced by the application of a large artificial electric field across the membrane. During electroporation in laboratory procedures, the lipid molecules are not chemically altered but simply shift position, opening up a pore (hole) that acts as the conductive pathway through the bilayer as it is filled with water. Experimentally, electroporation is used to introduce hydrophilic molecules into cells. It is a particularly useful technique for large highly charged molecules such as DNA and RNA, which would never passively diffuse across the hydrophobic bilayer core. Because of this, electroporation is one of the key methods of transfection as well as bacterial transformation.

A similar transfer of content across protocells and with the surrounding solution can also be caused by freezing and subsequent thawing. For example, this could occur in an environment in which day and night cycles cause recurrent freezing. Laboratory experiments have shown that such conditions allow an exchange of genetic information between populations of protocells. This can be explained by the fact that membranes are highly permeable at temperatures slightly below their phase transition temperature. If this point is reached during the freeze-thaw cycle, even large and highly charged molecules like nucleic acids can temporarily pass the protocell membrane.

Some molecules or particles are too large or too hydrophilic to pass through a lipid bilayer even under these conditions, but can be moved across the membrane through fusion or budding of vesicles, events which have also been observed for freeze-thaw cycles. This may eventually have led to mechanisms that facilitate movement of molecules to the inside of the protocell (endocytosis) or to release its contents into the extracellular space (exocytosis).

Artificial models

Langmuir-Blodgett deposition

Starting with a technique commonly used to deposit molecules on a solid surface, Langmuir–Blodgett deposition, scientists are able to assemble phospholipid membranes of arbitrary complexity layer by layer. These artificial phospholipid membranes support functional insertion both of purified and of in situ expressed membrane proteins. The technique could help astrobiologists understand how the first living cells originated.Jeewanu protocells

Surfactant molecules arranged on an air – water interface

Jeewanu protocells are synthetic chemical particles that possess cell-like structure and seem to have some functional living properties. First synthesized in 1963 from simple minerals and basic organics while exposed to sunlight, it is still reported to have some metabolic capabilities, the presence of semipermeable membrane, amino acids, phospholipids, carbohydrates and RNA-like molecules. However, the nature and properties of the Jeewanu remains to be clarified.

In a similar synthesis experiment a frozen mixture of water, methanol, ammonia and carbon monoxide was exposed to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. This combination yielded large amounts of organic material that self-organised to form globules or vesicles when immersed in water. The investigating scientist considered these globules to resemble cell membranes that enclose and concentrate the chemistry of life, separating their interior from the outside world. The globules were between 10 to 40 micrometres (0.00039 to 0.00157 in), or about the size of red blood cells. Remarkably, the globules fluoresced, or glowed, when exposed to UV light. Absorbing UV and converting it into visible light in this way was considered one possible way of providing energy to a primitive cell. If such globules played a role in the origin of life, the fluorescence could have been a precursor to primitive photosynthesis. Such fluorescence also provides the benefit of acting as a sunscreen, diffusing any damage that otherwise would be inflicted by UV radiation. Such a protective function would have been vital for life on the early Earth, since the ozone layer, which blocks out the sun's most destructive UV rays, did not form until after photosynthetic life began to produce oxygen.