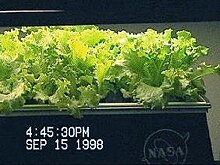

Lettuce and wheat grown in an aeroponic apparatus, NASA, 1998

Aeroponics is the process of growing plants in an air or mist environment without the use of soil or an aggregate medium (known as geoponics). The word "aeroponic" is derived from the Greek meanings of aer (ἀήρ, "air") and ponos (πόνος, "labour"). Aeroponic culture differs from both conventional hydroponics, aquaponics, and in-vitro (plant tissue culture)

growing. Unlike hydroponics, which uses a liquid nutrient solution as a

growing medium and essential minerals to sustain plant growth; or

aquaponics which uses water and fish waste, aeroponics is conducted

without a growing medium. It is sometimes considered a type of hydroponics, since water is used in aeroponics to transmit nutrients.

Methods

The basic principle of aeroponic growing is to grow plants suspended in a closed or semi-closed environment by spraying the plant's dangling roots and lower stem with an atomized or sprayed, nutrient-rich water solution. The leaves and crown, often called the canopy, extend above. The roots of the plant are separated by the plant support structure. Often, closed-cell foam

is compressed around the lower stem and inserted into an opening in the

aeroponic chamber, which decreases labor and expense; for larger

plants, trellising is used to suspend the weight of vegetation and fruit.

Ideally, the environment is kept free from pests and disease so that the plants may grow healthier and more quickly than plants grown in a medium.

However, since most aeroponic environments are not perfectly closed

off to the outside, pests and disease may still cause a threat.

Controlled environments advance plant development, health, growth,

flowering and fruiting for any given plant species and cultivars.

Due to the sensitivity of root systems, aeroponics is often combined with conventional hydroponics, which is used as an emergency "crop saver" – backup nutrition and water supply – if the aeroponic apparatus fails.

High-pressure aeroponics is defined as delivering nutrients to

the roots via 20–50 micrometre mist heads using a high-pressure (80

pounds per square inch (550 kPa)) diaphragm pump.

Benefits and drawbacks

Many types of plants can be grown aeroponically.

Increased air exposure

Close-up

of the first patented aeroponic plant support structure (1983). Its

unrestricted support of the plant allows for normal growth in the

air/moisture environment, and is still in use today.

Air cultures optimize access to air for successful plant growth.

Materials and devices which hold and support the aeroponic grown plants

must be devoid of disease or pathogens. A distinction of a true

aeroponic culture and apparatus is that it provides plant support

features that are minimal. Minimal contact between a plant and support

structure allows for 100% of the plant to be entirely in air. Long-term

aeroponic cultivation requires the root systems to be free of

constraints surrounding the stem and root systems. Physical contact is

minimized so that it does not hinder natural growth and root expansion

or access to pure water, air exchange and disease-free conditions.

Benefits of oxygen in the root zone

Oxygen (O2) in the rhizosphere (root zone) is necessary for healthy plant growth. As aeroponics is conducted in air combined with micro-droplets of water, almost any plant can grow to maturity in air with a plentiful supply of oxygen, water and nutrients.

Some growers favor aeroponic systems over other methods of hydroponics because the increased aeration of nutrient solution delivers more oxygen to plant roots, stimulating growth and helping to prevent pathogen formation.

Clean air supplies oxygen which is an excellent purifier for

plants and the aeroponic environment. For natural growth to occur, the

plant must have unrestricted access to air. Plants must be allowed to

grow in a natural manner for successful physiological development. The

more confining the plant support becomes, the greater incidence of

increasing disease pressure of the plant and the aeroponic system.

Some researchers have used aeroponics to study the effects of

root zone gas composition on plant performance. Soffer and Burger

[Soffer et al., 1988] studied the effects of dissolved oxygen

concentrations on the formation of adventitious roots in what they

termed “aero-hydroponics.” They utilized a 3-tier hydro and aero system,

in which three separate zones were formed within the root area. The

ends of the roots were submerged in the nutrient reservoir, while the

middle of the root section received nutrient mist and the upper portion

was above the mist. Their results showed that dissolved O2 is essential to root formation, but went on to show that for the three O2

concentrations tested, the number of roots and root length were always

greater in the central misted section than either the submersed section

or the un-misted section. Even at the lowest concentration, the misted

section rooted successfully.

Other benefits of air (CO2)

Plants in a true aeroponic apparatus have 100% access to the CO2 concentrations ranging from 450 ppm to 780 ppm for photosynthesis. At one mile (1.6 km) above sea level, the CO2 concentration in the air is 450 ppm during daylight. At night, the CO2

level will rise to 780 ppm. Lower elevations will have higher levels.

In any case, the air culture apparatus offers the ability for plants to

have full access to all of the available CO2 in the air for photosynthesis.

Growing under lights during the evening allows aeroponics to benefit from the natural occurrence.

Disease-free cultivation

Aeroponics

can limit disease transmission since plant-to-plant contact is reduced

and each spray pulse can be sterile. In the case of soil, aggregate, or

other media, disease can spread throughout the growth media, infecting

many plants. In most greenhouses, these solid media require

sterilization after each crop and, in many cases, they are simply

discarded and replaced with fresh, sterile media.

A distinct advantage of aeroponic technology is that if a particular plant does become diseased, it can be quickly removed from the plant support structure without disrupting or infecting the other plants.

Basil grown from seed in an aeroponic system located inside a modern greenhouse was first achieved 1986.

Due to the disease-free environment that is unique to aeroponics,

many plants can grow at higher density (plants per square meter) when

compared to more traditional forms of cultivation (hydroponics,

soil and Nutrient Film Technique [NFT]). Commercial aeroponic systems

incorporate hardware features that accommodate the crop's expanding root

systems.

Researchers have described aeroponics as a "valuable, simple, and

rapid method for preliminary screening of genotypes for resistance to

specific seedling blight or root rot.”

The isolating nature of the aeroponic system allowed them to

avoid the complications encountered when studying these infections in

soil culture.

Water and nutrient hydro-atomization

Aeroponic

equipment involves the use of sprayers, misters, foggers, or other

devices to create a fine mist of solution to deliver nutrients to plant

roots. Aeroponic systems are normally closed-looped systems providing

macro and micro-environments suitable to sustain a reliable, constant

air culture. Numerous inventions have been developed to facilitate

aeroponic spraying and misting. The key to root development in an

aeroponic environment is the size of the water droplet. In commercial

applications, a hydro-atomizing spray at 360° is employed to cover large

areas of roots utilizing air pressure misting.

A variation of the mist technique employs the use of ultrasonic foggers to mist nutrient solutions in low-pressure aeroponic devices.

Water droplet size is crucial for sustaining aeroponic growth.

Too large a water droplet means less oxygen is available to the root

system. Too fine a water droplet, such as those generated by the

ultrasonic mister, produce excessive root hair without developing a lateral root system for sustained growth in an aeroponic system.

Mineralization of the ultrasonic transducers

requires maintenance and potential for component failure. This is also a

shortcoming of metal spray jets and misters. Restricted access to the

water causes the plant to lose turgidity and wilt.

Advanced materials

NASA

has funded research and development of new advanced materials to

improve aeroponic reliability and maintenance reduction. It also has

determined that high pressure hydro-atomized mist of 5-50 micrometres

micro-droplets is necessary for long-term aeroponic growing.

For long-term growing, the mist system must have significant pressure to force the mist into the dense root system(s). Repeatability is the key to aeroponics and includes the hydro-atomized droplet size. Degradation

of the spray due to mineralization of mist heads inhibits the delivery

of the water nutrient solution, leading to an environmental imbalance in

the air culture environment.

Special low-mass polymer materials were developed and are used to eliminate mineralization in next generation hydro-atomizing misting and spray jets.

Nutrient uptake

Close-up of roots grown from wheat seed using aeroponics, 1998

The discrete nature of interval and duration aeroponics allows the

measurement of nutrient uptake over time under varying conditions.

Barak et al. used an aeroponic system for non-destructive measurement of

water and ion uptake rates for cranberries (Barak, Smith et al. 1996).

In their study, these researchers found that by measuring the concentrations and volumes of input and efflux solutions, they could accurately calculate the nutrient uptake rate (which was verified by comparing the results with N-isotope

measurements). After verification of their analytical method, Barak et

al. went on to generate additional data specific to the cranberry, such

as diurnal variation in nutrient uptake, correlation between ammonium uptake and proton

efflux, and the relationship between ion concentration and uptake.

Work such as this not only shows the promise of aeroponics as a research

tool for nutrient uptake, but also opens up possibilities for the

monitoring of plant health and optimization of crops grown in closed

environments.

Atomization (>65 pounds per square inch (450 kPa)), increases

bioavailability of nutrients, consequently, nutrient strength must be

significantly reduced or leaf and root burn will develop. Note the large

water droplets in the photo to the right. This is caused by the feed

cycle being too long or the pause cycle too short; either discourages

both lateral root growth and root hair development. Plant growth and

fruiting times are significantly shortened when feed cycles are as short

as possible. Ideally, roots should never be more than slightly damp

nor overly dry. A typical feed/pause cycle is < 2 seconds on,

followed by ~1.5-2 minute pause- 24/7, however, when an accumulator

system is incorporated, cycle times can be further reduced to < ~1

second on, ~1 minute pause.

As a research tool

Soon

after its development, aeroponics took hold as a valuable research

tool. Aeroponics offered researchers a noninvasive way to examine roots

under development. This new technology also allowed researchers a larger

number and a wider range of experimental parameters to use in their

work.

The ability to precisely control the root zone moisture levels

and the amount of water delivered makes aeroponics ideally suited for

the study of water stress. K. Hubick evaluated aeroponics as a means to

produce consistent, minimally water-stressed plants for use in drought

or flood physiology experiments.

Aeroponics is the ideal tool for the study of root morphology.

The absence of aggregates offers researchers easy access to the entire,

intact root structure without the damage that can be caused by removal

of roots from soils or aggregates. It’s been noted that aeroponics

produces more normal root systems than hydroponics.

Terminology

- Aeroponic growing refers to plants grown in an air culture that can develop and grow in a normal and natural manner.

- Aeroponic growth refers to growth achieved in an air culture.

- Aeroponic system refers to hardware and system components assembled to sustain plants in an air culture.

- Aeroponic greenhouse refers to a climate controlled glass or plastic structure with equipment to grow plants in air/mist environment.

- Aeroponic conditions refers to air culture environmental parameters for sustaining plant growth for a plant species.

- Aeroponic roots refers to a root system grown in an air culture.

Types of aeroponics

Low-pressure units

In most low-pressure aeroponic gardens, the plant roots are suspended above a reservoir

of nutrient solution or inside a channel connected to a reservoir. A

low-pressure pump delivers nutrient solution via jets or by ultrasonic

transducers, which then drips or drains back into the reservoir. As

plants grow to maturity in these units they tend to suffer from dry

sections of the root systems, which prevent adequate nutrient uptake.

These units, because of cost, lack features to purify the nutrient

solution, and adequately remove incontinuities, debris, and unwanted pathogens. Such units are usually suitable for bench top growing and demonstrating the principles of aeroponics.

High-pressure devices

High-pressure

aeroponic techniques, where the mist is generated by high-pressure

pump(s), are typically used in the cultivation of high value crops and

plant specimens that can offset the high setup costs associated with

this method of horticulture.

High-pressure aeroponics systems include technologies for air and water purification, nutrient sterilization, low-mass polymers and pressurized nutrient delivery systems.

Commercial systems

Commercial aeroponic systems comprise high-pressure device hardware and biological systems. The biological systems matrix includes enhancements for extended plant life and crop maturation.

Biological subsystems and hardware components include effluent

controls systems, disease prevention, pathogen resistance features,

precision timing and nutrient solution pressurization, heating and

cooling sensors, thermal control of solutions, efficient photon-flux light arrays, spectrum filtration spanning, fail-safe sensors and protection, reduced maintenance & labor saving features, and ergonomics and long-term reliability features.

Commercial aeroponic systems, like the high-pressure devices, are used for the cultivation of high value crops where multiple crop rotations are achieved on an ongoing commercial basis.

Advanced commercial systems include data gathering, monitoring, analytical feedback and internet connections to various subsystems.

History

In 1911, V.M.Artsikhovski published in the journal "Experienced

Agronomy" an article "On Air Plant Cultures", which talks about his

method of physiological studies of root systems by spraying various

substances in the surrounding air - the aeroponics method. He designed

the first aeroponics and in practice showed their suitability for plant

cultivation.

It was W. Carter in 1942 who first researched air culture growing

and described a method of growing plants in water vapor to facilitate

examination of roots.

As of 2006, aeroponics is used in agriculture around the globe.

In 1944, L.J. Klotz was the first to discover vapor misted citrus

plants in a facilitated research of his studies of diseases of citrus

and avocado roots. In 1952, G.F. Trowel grew apple trees in a spray

culture.

It was F. W. Went in 1957 who first coined the air-growing

process as “aeroponics”, growing coffee plants and tomatoes with

air-suspended roots and applying a nutrient mist to the root section.

Genesis Machine, 1983

GTi’s Genesis Rooting System, 1983

The first commercially available aeroponic apparatus was manufactured and marketed by GTi in 1983. It was known then as the Genesis Machine - taken from the movie Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. The Genesis Machine was marketed as the "Genesis Rooting System".

GTi's device incorporated an open-loop water driven apparatus, controlled by a microchip, and delivered a high pressure, hydro-atomized nutrient spray inside an aeroponic chamber.

At the time, the achievement was revolutionary in terms of a developing (artificial air culture) technology. The Genesis Machine simply connected to a water faucet and an electrical outlet.

Aeroponic propagation (cloning)

GTi's apparatus cut-away of vegetative cutting propagated aeroponically, achieved 1983

Aeroponic culturing revolutionized cloning (propagation from cutting)

of plants. Firstly, aeroponics allowed the whole process to be carried

out in a single, automated unit. Numerous plants which were previously considered difficult, or impossible, to propagate from cuttings could now be replicated simply from a single stem cutting. This was a major boon to green houses attempting to propagate delicate hardwoods or cacti – plants normally propagated by seed due to the likeliness of bacterial infection in cuttings.

Aeroponics has now largely surpassed hydroponics and tissue culture as means for sterile propagation of plant species. With the Genesis Machine,

or other comparable aeroponics setup, any grower could clone plants.

Due to the automation of most parts of the process, plants could be

cloned and grown by the hundreds or even thousands. In short, cloning

became easier because the aeroponic apparatus initiated faster and

cleaner root development through a sterile, nutrient rich, highly

oxygenated, and moist environment (Hughes, 1983).

Air-rooted transplants

Cloned aeroponics transplanted directly into soil

Aeroponics significantly advanced tissue culture technology. It

cloned plants in less time and reduced numerous labor steps associated

with tissue culture techniques. Aeroponics could eliminate stage I and

stage II plantings into soil (the bane of all tissue culture growers).

Tissue culture plants must be planted in a sterile media (stage-I) and

expanded out for eventual transfer into sterile soil (stage-II). After

they are strong enough they are transplanted directly to field soil.

Besides being labor-intensive, the entire process of tissue culture is

prone to disease, infection, and failure.

With the use of aeroponics, growers cloned

and transplanted air-rooted plants directly into field soil. Aeroponic

roots were not susceptible to wilting and leaf loss, or loss due to

transplant shock (something hydroponics can never overcome). Because of

their healthiness, air-rooted plants were less likely to be infected

with pathogens. (If the RH of the root chamber gets above 70 degrees F, fungus gnats, algae, anaerobic bacteria are likely to develop.)

The efforts by GTi ushered in a new era of artificial life

support for plants capable of growing naturally without the use of soil

or hydroponics. GTi received a patent for an all-plastic aeroponic

method and apparatus, controlled by a microprocessor in 1985.

Aeroponics became known as a time and cost saver. The economic factors of aeroponic’s contributions to agriculture were taking shape.

Genesis Growing System, 1985

GTi's Aeroponic Growing System greenhouse facility, 1985

By 1985, GTi introduced second generation aeroponics hardware, known

as the "Genesis Growing System". This second generation aeroponic

apparatus was a closed-loop system. It utilized recycled effluent

precisely controlled by a microprocessor. Aeroponics graduated to the

capability of supporting seed germination, thus making GTi's the world's

first plant and harvest aeroponic system.

Many of these open-loop unit and closed-loop aeroponic systems are still in operation today.

Commercialization

Aeroponics

eventually left the laboratories and entered into the commercial

cultivation arena. In 1966, commercial aeroponic pioneer B. Briggs

succeeded in inducing roots on hardwood cuttings by air-rooting. Briggs

discovered that air-rooted cuttings were tougher and more hardened than

those formed in soil and concluded that the basic principle of

air-rooting is sound. He discovered air-rooted trees could be

transplanted to soil without suffering from transplant shock or setback

to normal growth. Transplant shock is normally observed in hydroponic transplants.

In Israel in 1982, L. Nir developed a patent for an aeroponic

apparatus using compressed low-pressure air to deliver a nutrient

solution to suspended plants, held by styrofoam, inside large metal containers.

In summer 1976, British researcher John Prewer carried out a series of aeroponic experiments near Newport, Isle of Wight, U.K., in which lettuces (variety Tom Thumb) were grown from seed to maturity in 22 days in polyethylene film tubes made rigid by pressurized air supplied by ventilating fans. The equipment used to convert the water-nutrient into fog droplets was supplied by Mee Industries of California.

"In 1984 in association with John Prewer, a commercial grower on the

Isle of Wight - Kings Nurseries - used a different design of aeroponics

system to grow strawberry

plants. The plants flourished and produced a heavy crop of strawberries

which were picked by the nursery's customers. The system proved

particularly popular with elderly

customers who appreciated the cleanliness, quality and flavor of the

strawberries, and the fact they did not have to stoop when picking the

fruit."

In 1983, R. Stoner filed a patent for the first microprocessor

interface to deliver tap water and nutrients into an enclosed aeroponic

chamber made of plastic. Stoner has gone on to develop numerous

companies researching and advancing aeroponic hardware, interfaces,

biocontrols and components for commercial aeroponic crop production.

The first commercial aeroponic greenhouse for aeroponic food production – 1986

In 1985, Stoner's company, GTi, was the first company to manufacture,

market and apply large-scale closed-loop aeroponic systems into

greenhouses for commercial crop production.

In the 1990s, GHE or General Hydroponics [Europe] thought to try

to introduce aeroponics to the hobby hydroponics market and finally came

to the Aerogarden system. However, this could not be classed as 'true'

aeroponics because the Aerogarden produced tiny droplets of solution

rather than a fine mist of solution; the fine mist was meant to

reproduce true Amazon rain. In any case, a product was introduced to

the market and the grower could broadly claim to be growing their

hydroponic produce aeroponically. A demand for aeroponic growing in the

hobby market had been established and moreover it was thought of

as the ultimate hydroponic growing technique. The difference between

true aeroponic mist growing and aeroponic droplet growing had become

very blurred in the eyes of many people.

At the end of the nineties, a UK firm, Nutriculture, was encouraged

enough by industry talk to trial true aeroponic growing; although these

trials showed positive results compared with more traditional growing

techniques such as NFT and Ebb & Flood there were drawbacks, namely

cost and maintenance. To accomplish true mist aeroponics a special pump

had to be used which also presented scalability problems.

Droplet-aeroponics was easier to manufacture, and as it produced

comparable results to mist-aeroponics, Nutriculture began development of

a scalable, easy to use droplet-aeroponic system. Through trials they

found that aeroponics was ideal for plant propagation;

plants could be propagated without medium and could even be grown-on.

In the end, Nutriculture acknowledged that better results could be

achieved if the plant was propagated in their branded X-stream aeroponic

propagator and moved on to a specially designed droplet-aeroponic

growing system - the Amazon.

Aeroponically grown food

In

1986, Stoner became the first person to market fresh aeroponically

grown food to a national grocery chain. He was interviewed on NPR and discussed the importance of the water conservation features of aeroponics for both modern agriculture and space.

Aeroponics in space

Space plants

NASA

life support GAP technology with untreated beans (left tube) and

biocontrol treated beans (right tube) returned from the Mir space

station aboard the space shuttle – September 1997

Plants were first taken into Earth's orbit in 1960 on two separate missions, Sputnik 4 and Discoverer 17. On the former mission, wheat, pea, maize, spring onion, and Nigella damascena seeds were carried into space, and on the latter mission Chlorella pyrenoidosa cells were brought into orbit.

Plant experiments were later performed on a variety of Bangladesh, China, and joint Soviet-American missions, including Biosatellite II (Biosatellite program), Skylab 3 and 4, Apollo-Soyuz, Sputnik, Vostok, and Zond. Some of the earliest research results showed the effect of low gravity on the orientation of roots and shoots (Halstead and Scott 1990).

Subsequent research went on to investigate the effect of low

gravity on plants at the organismic, cellular, and subcellular levels.

At the organismic level, for example, a variety of species, including pine, oat, mung bean, lettuce, cress, and Arabidopsis thaliana,

showed decreased seedling, root, and shoot growth in low gravity,

whereas lettuce grown on Cosmos showed the opposite effect of growth in

space (Halstead and Scott 1990). Mineral uptake seems also to be

affected in plants grown in space. For example, peas grown in space

exhibited increased levels of phosphorus and potassium and decreased levels of the divalent cations calcium, magnesium, manganese, zinc, and iron (Halstead and Scott 1990).

Biocontrols in space

In

1996, NASA sponsored Stoner’s research for a natural liquid biocontrol,

known then as ODC (organic disease control), that activates plants to

grow without the need for pesticides as a means to control pathogens in a

closed-loop culture system. ODC is derived from natural aquatic

materials.

By 1997, Stoner’s biocontrol experiments were conducted by NASA.

BioServe Space Technologies’s GAP technology (miniature growth

chambers) delivered the ODC solution unto bean seeds. Triplicate ODC

experiments were conducted in GAP’s flown to the MIR by the space

shuttle; at the Kennedy Space Center; and at Colorado State University

(J. Linden). All GAPS were housed in total darkness to eliminate light

as an experiment variable. The NASA experiment was to study only the

benefits of the biocontrol.

NASA's experiments aboard the MIR space station and shuttle

confirmed that ODC elicited increased germination rate, better

sprouting, increased growth and natural plant disease mechanisms when

applied to beans in an enclosed environment. ODC is now a standard for pesticide-free aeroponic growing and organic farming. Soil and hydroponics growers can benefit by incorporating ODC into their planting techniques. ODC meets USDA NOP standards for organic farms.

Aeroponics for space and Earth

NASA aeroponic lettuce seed germination. Day 30.

In 1998, Stoner received NASA funding to develop a high performance

aeroponic system for earth and space. Stoner demonstrated that a dry

bio-mass of lettuce can be significantly increased with aeroponics. NASA

utilized numerous aeroponic advancements developed by Stoner. Due to

this advancement we can use as a reference to space aeroponics.

Abstract: The purpose of the research conducted was to identify

and demonstrate technologies for high-performance plant growth in a

variety of gravitational environments. A low-gravity environment, for

example, poses the problems of effectively bringing water and other

nutrients to the plants and effecting recovery of effluents. Food

production in the low-gravity environment of space provides further

challenges, such as minimization of water use, water handling, and

system weight. Food production on planetary bodies such as the Moon or

Mars also requires dealing with a hypogravity environment. Because of

the impacts to fluid dynamics in these various gravity environments, the

nutrient delivery system has been a major focus in plant growth system

optimization.

There are a number of methods currently utilized (both in low

gravity and on Earth) to deliver nutrients to plants. Substrate

dependent methods include traditional soil cultivation, zeoponics, agar,

and nutrient-loaded ion exchange resins. In addition to substrate

dependent cultivation, many methods using no soil have been developed

such as nutrient film technique, ebb and flow, aeroponics, and many

other variants. Many hydroponic systems can provide high plant

performance but nutrient solution throughput is high, necessitating

large water volumes and substantial recycling of solutions, and the

control of the solution in hypogravity conditions is difficult at best.

Aeroponics, with its use of a hydro-atomized spray to deliver

nutrients, minimizes water use, increases oxygenation of roots, and

offers excellent plant growth, while at the same time approaching or

bettering the low nutrient solution throughput of other systems

developed to operate in low gravity. Aeroponics’ elimination of

substrates and the need for large nutrient stockpiles reduces the amount

of waste materials to be processed by other life support systems.

Furthermore, the absence of substrates simplifies planting and

harvesting (providing opportunities for automation), decreases the

volume and weight of expendable materials, and eliminates a pathway for

pathogen transmission. These many advantages combined with the results

of this research that prove the viability of aeroponics in microgravity

makes aeroponics a logical choice for efficient food production in

space.]

NASA inflatable aeroponics

In

1999, Stoner, funded by NASA, developed an inflatable low-mass

aeroponic system (AIS) for space and earth for high performance food

production.This advancements are very useful in space aeroponics.

Abstract: Aeroponics International’s (AI’s) innovation is a

self-contained, self-supporting, inflatable aeroponic crop production

unit with integral environmental systems for the control and delivery of

a nutrient/mist to the roots. This inflatable aeroponic system

addresses the needs of subtopic 08.03 Spacecraft Life Support

Infrastructure and, in particular, water and nutrient delivery systems

technologies for food production. The inflatable nature of our

innovation makes it lightweight, allowing it to be deflated so it takes

up less volume during transportation and storage. It improves on AI’s

current aeroponic system design that uses rigid structures, which use

more expensive materials, manufacture processes, and transportation. As a

stationary aeroponic system, these existing high-mass units perform

very well, but transporting and storing them can be problematic.

On Earth, these problems may hinder the economic feasibility of

aeroponics for commercial growers. However, such problems become

insurmountable obstacles for using these systems on long-duration space

missions because of the high cost of payload volume and mass during

launch and transit.

The NASA efforts lead to developments of numerous advanced materials for aeroponics for earth and space.

Benefits of aeroponics for earth and space

NASA aeroponic lettuce seed germination- Day 3

Aeroponics possesses many characteristics that make it an effective and efficient means of growing plants.

Less nutrient solution throughout

NASA aeroponic lettuce seed germination- Day 12

Plants grown using aeroponics spend 99.98% of their time in air and

0.02% in direct contact with hydro-atomized nutrient solution. The time

spent without water allows the roots to capture oxygen more efficiently.

Furthermore, the hydro-atomized mist also significantly contributes to

the effective oxygenation of the roots. For example, NFT has a

nutrient throughput of 1 liter per minute compared to aeroponics’

throughput of 1.5 milliliters per minute.

The reduced volume of nutrient throughput results in reduced amounts of nutrients required for plant development.

Another benefit of the reduced throughput, of major significance

for space-based use, is the reduction in water volume used. This

reduction in water volume throughput corresponds with a reduced buffer

volume, both of which significantly lighten the weight needed to

maintain plant growth. In addition, the volume of effluent from the

plants is also reduced with aeroponics, reducing the amount of water

that needs to be treated before reuse.

The relatively low solution volumes used in aeroponics, coupled

with the minimal amount of time that the roots are exposed to the

hydro-atomized mist, minimizes root-to-root contact and spread of

pathogens between plants.

Greater control of plant environment

NASA aeroponic lettuce seed germination (close-up of root zone environment)- Day 19

Aeroponics allows more control of the environment around the root

zone, as, unlike other plant growth systems, the plant roots are not

constantly surrounded by some medium (as, for example, with hydroponics,

where the roots are constantly immersed in water).

Improved nutrient feeding

A

variety of different nutrient solutions can be administered to the root

zone using aeroponics without needing to flush out any solution or

matrix in which the roots had previously been immersed. This elevated

level of control would be useful when researching the effect of a varied

regimen of nutrient application to the roots of a plant species of

interest.

In a similar manner, aeroponics allows a greater range of growth

conditions than other nutrient delivery systems. The interval and

duration of the nutrient spray, for example, can be very finely attuned

to the needs of a specific plant species.

The aerial tissue can be subjected to a completely different environment

from that of the roots.

More user-friendly

The

design of an aeroponic system allows ease of working with the plants.

This results from the separation of the plants from each other, and the

fact that the plants are suspended in air and the roots are not

entrapped in any kind of matrix. Consequently, the harvesting of

individual plants is quite simple and straightforward. Likewise,

removal of any plant that may be infected with some type of pathogen is

easily accomplished without risk of uprooting or contaminating nearby

plants.

More cost effective

Close-up of aeroponically grown corn and roots inside an aeroponic (air-culture) apparatus, 2005

Aeroponic systems are more cost effective than other systems.

Because of the reduced volume of solution throughput (discussed above),

less water and fewer nutrients are needed in the system at any given

time compared to other nutrient delivery systems. The need for

substrates is also eliminated, as is the need for many moving parts .

Use of seed stocks

With

aeroponics, the deleterious effects of seed stocks that are infected

with pathogens can be minimized. As discussed above, this is due to the

separation of the plants and the lack of shared growth matrix. In

addition, due to the enclosed, controlled environment, aeroponics can be

an ideal growth system in which to grow seed stocks that are

pathogen-free. The enclosing of the growth chamber, in addition to the

isolation of the plants from each other discussed above, helps to both

prevent initial contamination from pathogens introduced from the

external environment and minimize the spread from one plant to others of

any pathogens that may exist.

21st century aeroponics

Modern

aeroponics allows high density companion planting of many food and

horticultural crops without the use of pesticides - due to unique

discoveries aboard the space shuttle

Aeroponics is an improvement in artificial life support for

non-damaging plant support, seed germination, environmental control and

rapid unrestricted growth when compared with hydroponics and drip

irrigation techniques that have been used for decades by traditional

agriculturalists.

Contemporary aeroponics

Contemporary aeroponic techniques have been researched at NASA's research and commercialization center

BioServe Space Technologies

located on the campus of the University of Colorado in Boulder,

Colorado. Other research includes enclosed loop system research at Ames Research Center, where scientists were studying methods of growing food crops in low gravity situations for future space colonization.

In 2000, Stoner was granted a patent for an organic disease

control biocontrol technology that allows for pesticide-free natural

growing in an aeroponic systems.

In 2004, Ed Harwood, founder of AeroFarms, invented an aeroponic system that grows lettuces on micro fleece cloth.

AeroFarms, utilizing Harwood's patented aeroponic technology, is now

operating the largest indoor vertical farm in the world based on annual

growing capacity in Newark, New Jersey. By using aeroponic technology

the farm is able to produce and sell up to two million pounds of

pesticide-free leafy greens per year.

Aeroponic bio-pharming

Aeroponically grown biopharma corn, 2005

Aeroponic bio-pharming is used to grow pharmaceutical medicine inside

of plants. The technology allows for completed containment of allow

effluents and by-products of biopharma crops to remain inside a

closed-loop facility.

As recently as 2005, GMO research at South Dakota State University by Dr. Neil Reese applied aeroponics to grow genetically modified corn.

According to Reese it is a historical feat to grow corn in an aeroponic apparatus for bio-massing. The university’s past attempts to grow all types of corn using hydroponics ended in failure.

Using advanced aeroponics techniques to grow genetically modified

corn Reese harvested full ears of corn, while containing the corn

pollen and spent effluent water and preventing them from entering the

environment. Containment of these by-products ensures the environment

remains safe from GMO contamination.

Reese says, aeroponics offers the ability to make bio-pharming economically practical.

Large scale integration of aeroponics

Aeroponic Graduate Program: Hanoi Agricultural University, Hanoi, Vietnam

In 2006, the Institute of Biotechnology at Vietnam National University of Agriculture,

in joint efforts with Stoner, established a postgraduate doctoral

program in aeroponics. The university's Agrobiotech Research Center,

under the direction of Professor Nguyen Quang Thach, is using aeroponic laboratories to advance Vietnam's minituber potato production for certified seed potato production.

Aeroponic potato explants on day 3 after insertion in the aeroponic system, Hanoi

The historical significance for aeroponics is that it is the first

time a nation has specifically called out for aeroponics to further an

agricultural sector, stimulate farm economic goals, meet increased

demands, improve food quality and increase production.

"We have shown that aeroponics, more than any other form of

agricultural technology, will significantly improve Vietnam's potato

production. We have very little tillable land, aeroponics makes complete

economic sense to us”, attested Thach.

Aeroponic greenhouse for potato minituber product Hanoi 2006

Vietnam joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in January 2007. The impact of aeroponics in Vietnam will be felt at the farm level.

Aeroponic integration in Vietnamese agriculture will begin by

producing a low cost certified disease-free organic minitubers, which in

turn will be supplied to local farmers for their field plantings of

seed potatoes and commercial potatoes. Potato farmers will benefit from

aeroponics because their seed potatoes will be disease-free and grown

without pesticides. Most importantly for the Vietnamese farmer, it will

lower their cost of operation and increase their yields, says Thach.