The flightless dung beetle occupies an ecological niche exploiting animal droppings as a food source.

In ecology, a niche (CanE, UK: /ˈniːʃ/ or US: /ˈnɪtʃ/) is the fit of a species living under specific environmental conditions. The ecological niche describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (for example, by growing when resources are abundant, and when predators, parasites and pathogens

are scarce) and how it in turn alters those same factors (for example,

limiting access to resources by other organisms, acting as a food source

for predators and a consumer of prey). "The type and number of

variables comprising the dimensions of an environmental niche vary from

one species to another [and] the relative importance of particular

environmental variables for a species may vary according to the

geographic and biotic contexts".

A Grinnellian niche is determined by the habitat in which a species lives and its accompanying behavioral adaptations.

An Eltonian niche emphasizes that a species not only grows in and

responds to an environment, it may also change the environment and its

behavior as it grows. The Hutchinsonian niche uses mathematics and

statistics to try to explain how species coexist within a given

community.

The notion of ecological niche is central to ecological biogeography, which focuses on spatial patterns of ecological communities.

"Species distributions and their dynamics over time result from

properties of the species, environmental variation..., and interactions

between the two—in particular the abilities of some species, especially

our own, to modify their environments and alter the range dynamics of

many other species." Alteration of an ecological niche by its inhabitants is the topic of niche construction.

The majority of species exist in a standard ecological niche, sharing behaviors, adaptations, and functional traits similar to the other closely related species within the same broad taxonomic class, but there are exceptions. A premier example of a non-standard niche filling species is the flightless, ground-dwelling kiwi bird of New Zealand, which feeds on worms and other ground creatures, and lives its life in a mammal-like niche. Island biogeography can help explain island species and associated unfilled niches.

Grinnellian niche

A niche: the place where a statue may stand

The ecological meaning of niche comes from the meaning of niche as a recess in a wall for a statue, which itself is probably derived from the Middle French word nicher, meaning to nest.

The term was coined by the naturalist Roswell Hill Johnson

but Joseph Grinnell

was probably the first to use it in a research program in 1917, in his

paper "The niche relationships of the California Thrasher".

The Grinnellian niche concept embodies the idea that the niche of a species is determined by the habitat in which it lives and its accompanying behavioral adaptations.

In other words, the niche is the sum of the habitat requirements and

behaviors that allow a species to persist and produce offspring. For

example, the behavior of the California thrasher is consistent with the chaparral

habitat it lives in—it breeds and feeds in the underbrush and escapes

from its predators by shuffling from underbrush to underbrush. Its

'niche' is defined by the felicitous complementing of the thrasher's

behavior and physical traits (camouflaging color, short wings, strong

legs) with this habitat.

This perspective of niche allows for the existence of both

ecological equivalents and empty niches. An ecological equivalent to an

organism is an organism from a different taxonomic group exhibiting

similar adaptations in a similar habitat, an example being the different

succulents found in American and African deserts, cactus and euphorbia, respectively. As another example, the anole lizards of the Greater Antilles are a rare example of convergent evolution, adaptive radiation, and the existence of ecological equivalents: the anole lizards evolved in similar microhabitats independently of each other and resulted in the same ecomorphs across all four islands.

Eltonian niche

In 1927 Charles Sutherland Elton, a British ecologist, defined a niche as follows: "The 'niche' of an animal means its place in the biotic environment, its relations to food and enemies."

Elton classified niches according to foraging activities ("food habits"):

For instance there is the niche that is filled by birds of prey which eat small animals such as shrews and mice. In an oak wood this niche is filled by tawny owls, while in the open grassland it is occupied by kestrels. The existence of this carnivore niche is dependent on the further fact that mice form a definite herbivore niche in many different associations, although the actual species of mice may be quite different.

Conceptually, the Eltonian niche introduces the idea of a species' response to and effect on

the environment. Unlike other niche concepts, it emphasizes that a

species not only grows in and responds to an environment based on

available resources, predators, and climatic conditions, but also

changes the availability and behavior of those factors as it grows. In

an extreme example, beavers

require certain resources in order to survive and reproduce, but also

construct dams that alter water flow in the river where the beaver

lives. Thus, the beaver affects the biotic and abiotic conditions of

other species that live in and near the watershed.

In a more subtle case, competitors that consume resources at different

rates can lead to cycles in resource density that differ between

species. Not only do species grow differently with respect to resource density, but their own population growth can affect resource density over time.

Hutchinsonian niche

The shape of the bill of this purple-throated carib is complementary to the shape of the flower and coevolved with it, enabling it to exploit the nectar as a resource.

The Hutchinsonian niche is an "n-dimensional hypervolume", where the dimensions are environmental conditions and resources,

that define the requirements of an individual or a species to practice

"its" way of life, more particularly, for its population to persist.

The "hypervolume" defines the multi-dimensional space of resources

(e.g., light, nutrients, structure, etc.) available to (and specifically

used by) organisms, and "all species other than those under

consideration are regarded as part of the coordinate system."

The niche concept was popularized by the zoologist G. Evelyn Hutchinson in 1957.

Hutchinson inquired into the question of why there are so many types of

organisms in any one habitat. His work inspired many others to develop

models to explain how many and how similar coexisting species could be

within a given community, and led to the concepts of 'niche breadth' (the variety of resources or habitats used by a given species), 'niche partitioning' (resource differentiation by coexisting species), and 'niche overlap' (overlap of resource use by different species).

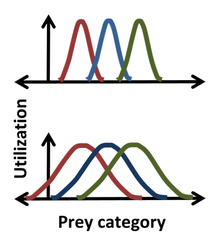

Where

three species eat some of the same prey, a statistical picture of each

niche shows overlap in resource usage between three species, indicating

where competition is strongest.

Statistics were introduced into the Hutchinson niche by Robert MacArthur and Richard Levins

using the 'resource-utilization' niche employing histograms to describe

the 'frequency of occurrence' as a function of a Hutchinson coordinate. So, for instance, a Gaussian

might describe the frequency with which a species ate prey of a certain

size, giving a more detailed niche description than simply specifying

some median or average prey size. For such a bell-shaped distribution,

the position, width and form of the niche correspond to the mean, standard deviation and the actual distribution itself. One advantage in using statistics is illustrated in the figure, where

it is clear that for the narrower distributions (top) there is no

competition for prey between the extreme left and extreme right species,

while for the broader distribution (bottom), niche overlap indicates

competition can occur between all species. The resource-utilization

approach consists in postulating that not only competition can occur, but also that it does occur, and that overlap in resource utilization directly enables the estimation of the competition coefficients.

This postulate, however, can be misguided, as it ignores the impacts

that the resources of each category have on the organism and the impacts

that the organism has on the resources of each category. For instance,

the resource in the overlap region can be non-limiting, in which case

there is no competition for this resource despite niche overlap.

An organism free of interference from other species could use the

full range of conditions (biotic and abiotic) and resources in which it

could survive and reproduce which is called its fundamental niche.

However, as a result of pressure from, and interactions with, other

organisms (i.e. inter-specific competition) species are usually forced

to occupy a niche that is narrower than this, and to which they are

mostly highly adapted; this is termed the realized niche.

Hutchinson used the idea of competition for resources as the primary

mechanism driving ecology, but overemphasis upon this focus has proved

to be a handicap for the niche concept.

In particular, overemphasis upon a species' dependence upon resources

has led to too little emphasis upon the effects of organisms on their

environment, for instance, colonization and invasions.

The term "adaptive zone" was coined by the paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson

to explain how a population could jump from one niche to another that

suited it, jump to an 'adaptive zone', made available by virtue of some

modification, or possibly a change in the food chain,

that made the adaptive zone available to it without a discontinuity in

its way of life because the group was 'pre-adapted' to the new

ecological opportunity.

As a hemi-parasitic plant, the mistletoe in this tree exploits its host for nutrients and as a place to grow.

Hutchinson's "niche" (a description of the ecological space occupied

by a species) is subtly different from the "niche" as defined by

Grinnell (an ecological role, that may or may not be actually filled by a

species—see vacant niches).

A niche is a very specific segment of ecospace occupied by a

single species. On the presumption that no two species are identical in

all respects (called Hardin's 'axiom of inequality') and the competitive exclusion principle, some resource or adaptive dimension will provide a niche specific to each species. Species can however share a 'mode of life' or 'autecological strategy' which are broader definitions of ecospace. For example, Australian grasslands species, though different from those of the Great Plains grasslands, exhibit similar modes of life.

Once a niche is left vacant, other organisms can fill that

position. For example, the niche that was left vacant by the extinction

of the tarpan has been filled by other animals (in particular a small horse breed, the konik).

Also, when plants and animals are introduced into a new environment,

they have the potential to occupy or invade the niche or niches of

native organisms, often outcompeting the indigenous species.

Introduction of non-indigenous species to non-native habitats by humans often results in biological pollution by the exotic or invasive species.

The mathematical representation of a species' fundamental niche

in ecological space, and its subsequent projection back into geographic

space, is the domain of niche modelling.

Parameters

The

different dimensions, or plot axes, of a niche represent different

biotic and abiotic variables. These factors may include descriptions of

the organism's life history, habitat, trophic position (place in the food chain), and geographic range. According to the competitive exclusion principle,

no two species can occupy the same niche in the same environment for a

long time. The parameters of a realized niche are described by the realized niche width of that species. Some plants and animals, called specialists, need specific habitats and surroundings to survive, such as the spotted owl,

which lives specifically in old growth forests. Other plants and

animals, called generalists, are not as particular and can survive in a

range of conditions, for example the dandelion.