Negative-index metamaterial array configuration, which was constructed of copper split-ring resonators

and wires mounted on interlocking sheets of fiberglass circuit board.

The total array consists of 3 by 20×20 unit cells with overall

dimensions of 10 mm × 100 mm × 100 mm (0.39 in × 3.94 in × 3.94 in).

A metamaterial (from the Greek word μετά meta, meaning "beyond") is a material engineered to have a property that is not found in naturally occurring materials.

They are made from assemblies of multiple elements fashioned from

composite materials such as metals or plastics. The materials are

usually arranged in repeating patterns, at scales that are smaller than

the wavelengths

of the phenomena they influence. Metamaterials derive their properties

not from the properties of the base materials, but from their newly

designed structures. Their precise shape, geometry, size, orientation and arrangement gives them their smart properties capable of manipulating electromagnetic waves:

by blocking, absorbing, enhancing, or bending waves, to achieve

benefits that go beyond what is possible with conventional materials.

Appropriately designed metamaterials can affect waves of electromagnetic radiation or sound in a manner not observed in bulk materials. Those that exhibit a negative index of refraction for particular wavelengths have attracted significant research. These materials are known as negative-index metamaterials.

Potential applications of metamaterials are diverse and include optical filters, medical devices, remote aerospace applications, sensor detection and infrastructure monitoring, smart solar power management, crowd control, radomes, high-frequency battlefield communication and lenses for high-gain antennas, improving ultrasonic sensors, and even shielding structures from earthquakes. Metamaterials offer the potential to create superlenses. Such a lens could allow imaging below the diffraction limit that is the minimum resolution that can be achieved by conventional glass lenses. A form of 'invisibility' was demonstrated using gradient-index materials. Acoustic and seismic metamaterials are also research areas.

Metamaterial research is interdisciplinary and involves such fields as electrical engineering, electromagnetics, classical optics, solid state physics, microwave and antenna engineering, optoelectronics, material sciences, nanoscience and semiconductor engineering.

History

Explorations of artificial materials for manipulating electromagnetic waves began at the end of the 19th century. Some of the earliest structures that may be considered metamaterials were studied by Jagadish Chandra Bose, who in 1898 researched substances with chiral properties. Karl Ferdinand Lindman studied wave interaction with metallic helices as artificial chiral media in the early twentieth century.

Winston E. Kock developed materials that had similar characteristics to metamaterials in the late 1940s. In the 1950s and 1960s, artificial dielectrics were studied for lightweight microwave antennas. Microwave radar absorbers were researched in the 1980s and 1990s as applications for artificial chiral media.

Negative-index materials were first described theoretically by Victor Veselago in 1967. He proved that such materials could transmit light. He showed that the phase velocity could be made anti-parallel to the direction of Poynting vector. This is contrary to wave propagation in naturally occurring materials.

John Pendry was the first to identify a practical way to make a left-handed metamaterial, a material in which the right-hand rule is not followed. Such a material allows an electromagnetic wave to convey energy (have a group velocity) against its phase velocity. Pendry's idea was that metallic wires aligned along the direction of a wave could provide negative permittivity (dielectric function ε < 0). Natural materials (such as ferroelectrics)

display negative permittivity; the challenge was achieving negative

permeability (µ < 0). In 1999 Pendry demonstrated that a split ring

(C shape) with its axis placed along the direction of wave propagation

could do so. In the same paper, he showed that a periodic array of wires

and rings could give rise to a negative refractive index. Pendry also

proposed a related negative-permeability design, the Swiss roll.

In 2000, Smith et al. reported the experimental demonstration of functioning electromagnetic metamaterials by horizontally stacking, periodically, split-ring resonators

and thin wire structures. A method was provided in 2002 to realize

negative-index metamaterials using artificial lumped-element loaded

transmission lines in microstrip technology. In 2003, complex (both real and imaginary parts of) negative refractive index and imaging by flat lens using left handed metamaterials were demonstrated. By 2007, experiments that involved negative refractive index had been conducted by many groups. At microwave frequencies, the first, imperfect invisibility cloak was realized in 2006.

Electromagnetic metamaterials

An electromagnetic metamaterial affects electromagnetic waves that impinge on or interact with its structural features, which are smaller than the wavelength. To behave as a homogeneous material accurately described by an effective refractive index, its features must be much smaller than the wavelength.

For microwave radiation, the features are on the order of millimeters.

Microwave frequency metamaterials are usually constructed as arrays of

electrically conductive elements (such as loops of wire) that have

suitable inductive and capacitive characteristics. One microwave metamaterial uses the split-ring resonator.

Photonic metamaterials, nanometer scale, manipulate light at optical frequencies. To date, subwavelength structures have shown only a few, questionable, results at visible wavelengths. Photonic crystals and frequency-selective surfaces such as diffraction gratings, dielectric mirrors and optical coatings

exhibit similarities to subwavelength structured metamaterials.

However, these are usually considered distinct from subwavelength

structures, as their features are structured for the wavelength at which

they function and thus cannot be approximated as a homogeneous

material. However, material structures such as photonic crystals are effective in the visible light spectrum.

The middle of the visible spectrum has a wavelength of approximately

560 nm (for sunlight). Photonic crystal structures are generally half

this size or smaller, that is <280 nbsp="" nm.="" p="">

Plasmonic metamaterials utilize surface plasmons, which are packets of electrical charge that collectively oscillate at the surfaces of metals at optical frequencies.

Frequency selective surfaces (FSS) can exhibit subwavelength characteristics and are known variously as artificial magnetic conductors

(AMC) or High Impedance Surfaces (HIS). FSS display inductive and

capacitive characteristics that are directly related to their

subwavelength structure.

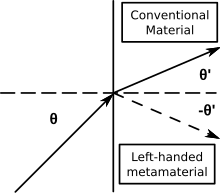

Negative refractive index

A comparison of refraction in a left-handed metamaterial to that in a normal material

Almost all materials encountered in optics, such as glass or water, have positive values for both permittivity ε and permeability µ. However, metals such as silver and gold have negative permittivity at shorter wavelengths. A material such as a surface plasmon that has either (but not both) ε or µ negative is often opaque to electromagnetic radiation. However, anisotropic materials with only negative permittivity can produce negative refraction due to chirality.

Although the optical properties of a transparent material are fully specified by the parameters εr and µr, refractive index n is often used in practice, which can be determined from . All known non-metamaterial transparent materials possess positive εr and µr. By convention the positive square root is used for n.

However, some engineered metamaterials have εr < 0 and µr < 0. Because the product εrµr is positive, n is real. Under such circumstances, it is necessary to take the negative square root for n.

Video representing negative refraction of light at uniform planar interface.

The foregoing considerations are simplistic for actual materials, which must have complex-valued εr and µr. The real parts of both εr and µr do not have to be negative for a passive material to display negative refraction. Metamaterials with negative n have numerous interesting properties:

- Snell's law (n1sinθ1 = n2sinθ2), but as n2 is negative, the rays are refracted on the same side of the normal on entering the material.

- Cherenkov radiation points the other way.

- The time-averaged Poynting vector is antiparallel to phase velocity. However, for waves (energy) to propagate, a –µ must be paired with a –ε in order to satisfy the wave number dependence on the material parameters .

Negative index of refraction derives mathematically from the vector triplet E, H and k.

For plane waves propagating in electromagnetic metamaterials, the electric field, magnetic field and wave vector follow a left-hand rule, the reverse of the behavior of conventional optical materials.

Classification

Negative index

In negative-index metamaterials (NIM), both permittivity and

permeability are negative, resulting in a negative index of refraction.

These are also known as double negative metamaterials or double

negative materials (DNG). Other terms for NIMs include "left-handed

media", "media with a negative refractive index", and "backward-wave

media".

In optical materials, if both permittivity ε and permeability µ

are positive, wave propagation travels in the forward direction. If

both ε and µ are negative, a backward wave is produced. If ε and µ have

different polarities, waves do not propagate.

Mathematically, quadrant II and quadrant IV have coordinates (0,0) in a coordinate plane where ε is the horizontal axis, and µ is the vertical axis.

To date, only metamaterials exhibit a negative index of refraction.

Single negative

Single negative (SNG) metamaterials have either negative relative permittivity (εr) or negative relative permeability (µr), but not both. They act as metamaterials when combined with a different, complementary SNG, jointly acting as a DNG.

Epsilon negative media (ENG) display a negative εr while µr is positive. Many plasmas exhibit this characteristic. For example, noble metals such as gold or silver are ENG in the infrared and visible spectrums.

Mu-negative media (MNG) display a positive εr and negative µr.

Gyrotropic or gyromagnetic materials exhibit this characteristic. A

gyrotropic material is one that has been altered by the presence of a

quasistatic magnetic field, enabling a magneto-optic effect.

A magneto-optic effect is a phenomenon in which an electromagnetic wave

propagates through such a medium. In such a material, left- and

right-rotating elliptical polarizations can propagate at different

speeds. When light is transmitted through a layer of magneto-optic

material, the result is called the Faraday effect: the polarization plane can be rotated, forming a Faraday rotator. The results of such a reflection are known as the magneto-optic Kerr effect (not to be confused with the nonlinear Kerr effect). Two gyrotropic materials with reversed rotation directions of the two principal polarizations are called optical isomers.

Joining a slab of ENG material and slab of MNG material resulted

in properties such as resonances, anomalous tunneling, transparency and

zero reflection. Like negative-index materials, SNGs are innately

dispersive, so their εr, µr and refraction index n, are a function of frequency.

Bandgap

Electromagnetic bandgap metamaterials (EBG or EBM) control light propagation. This is accomplished either with photonic crystals

(PC) or left-handed materials (LHM). PCs can prohibit light propagation

altogether. Both classes can allow light to propagate in specific,

designed directions and both can be designed with bandgaps at desired

frequencies. The period size of EBGs is an appreciable fraction of the wavelength, creating constructive and destructive interference.

PC are distinguished from sub-wavelength structures, such as tunable metamaterials,

because the PC derives its properties from its bandgap characteristics.

PCs are sized to match the wavelength of light, versus other

metamaterials that expose sub-wavelength structure. Furthermore, PCs

function by diffracting light. In contrast, metamaterial does not use

diffraction.

PCs have periodic inclusions that inhibit wave propagation due to

the inclusions' destructive interference from scattering. The photonic

bandgap property of PCs makes them the electromagnetic analog of

electronic semi-conductor crystals.

EBGs have the goal of creating high quality, low loss, periodic,

dielectric structures. An EBG affects photons in the same way

semiconductor materials affect electrons. PCs are the perfect bandgap

material, because they allow no light propagation. Each unit of the prescribed periodic structure acts like one atom, albeit of a much larger size.

EBGs are designed to prevent the propagation of an allocated bandwidth of frequencies, for certain arrival angles and polarizations.

Various geometries and structures have been proposed to fabricate EBG's

special properties. In practice it is impossible to build a flawless

EBG device.

EBGs have been manufactured for frequencies ranging from a few

gigahertz (GHz) to a few terahertz (THz), radio, microwave and

mid-infrared frequency regions. EBG application developments include a transmission line, woodpiles made of square dielectric bars and several different types of low gain antennas.

Double positive medium

Double positive mediums (DPS) do occur in nature, such as naturally occurring dielectrics.

Permittivity and magnetic permeability are both positive and wave

propagation is in the forward direction. Artificial materials have been

fabricated which combine DPS, ENG and MNG properties.

Bi-isotropic and bianisotropic

Categorizing

metamaterials into double or single negative, or double positive,

normally assumes that the metamaterial has independent electric and

magnetic responses described by ε and µ. However, in many cases, the electric field causes magnetic

polarization, while the magnetic field induces electrical polarization,

known as magnetoelectric coupling. Such media are denoted as bi-isotropic. Media that exhibit magnetoelectric coupling and that are anisotropic (which is the case for many metamaterial structures), are referred to as bi-anisotropic.

Four material parameters are intrinsic to magnetoelectric coupling of bi-isotropic media. They are the electric (E) and magnetic (H) field strengths, and electric (D) and magnetic (B) flux densities. These parameters are ε, µ, κ

and χ or permittivity, permeability, strength of chirality, and the

Tellegen parameter respectively. In this type of media, material

parameters do not vary with changes along a rotated coordinate system of measurements. In this sense they are invariant or scalar.

The intrinsic magnetoelectric parameters, κ and χ, affect the phase

of the wave. The effect of the chirality parameter is to split the

refractive index. In isotropic media this results in wave propagation

only if ε and µ have the same sign. In bi-isotropic media with χ assumed to be zero, and κ

a non-zero value, different results appear. Either a backward wave or a

forward wave can occur. Alternatively, two forward waves or two

backward waves can occur, depending on the strength of the chirality

parameter.

In the general case, the constitutive relations for bi-anisotropic materials read

where and are the permittivity and the permeability tensors, respectively, whereas and are the two magneto-electric tensors. If the medium is reciprocal, permittivity and permeability are symmetric tensors, and , where

is the chiral tensor describing chiral electromagnetic and reciprocal

magneto-electric response. The chiral tensor can be expressed as , where is the trace of ,

I is the identity matrix, N is a symmetric trace-free tensor, and J is

an antisymmetric tensor. Such decomposition allows us to classify the

reciprocal bianisotropic response and we can identify the following

three main classes: (i) chiral media (), (ii) pseudochiral media (), (iii) omega media ().

Generally the chiral and/or bianisotropic electromagnetic response is a

consequence of 3D geometrical chirality: 3D chiral metamaterials are

composed by embedding 3D chiral structures in a host medium and they

show chirality-related polarization effects such as optical activity and

circular dichroism. The concept of 2D chirality also exists and a

planar object is said to be chiral if it cannot be superposed onto its

mirror image unless it is lifted from the plane. On the other hand,

bianisotropic response can arise from geometrical achiral structures

possessing neither 2D nor 3D intrinsic chirality. Plum et al. investigated extrinsic chiral metamaterials where the magneto-electric

coupling results from the geometric chirality of the whole structure

and the effect is driven by the radiation wave vector contributing to

the overall chiral asymmetry (extrinsic electromagnetic chiralilty).

Rizza et al. suggested 1D chiral metamaterials where the effective chiral tensor is

not vanishing if the system is geometrically one-dimensional chiral (the

mirror image of the entire structure cannot be superposed onto it by

using translations without rotations).

Chiral

Chiral metamaterials are constructed from chiral materials in which the effective parameter k is non-zero. This is a potential source of confusion as the metamaterial literature includes two conflicting uses of the terms left- and right-handed.

The first refers to one of the two circularly polarized waves that are

the propagating modes in chiral media. The second relates to the triplet

of electric field, magnetic field and Poynting vector that arise in

negative refractive index media, which in most cases are not chiral.

Wave propagation properties in chiral metamaterials demonstrate

that negative refraction can be realized in metamaterials with a strong

chirality and positive ε and μ. This is because the refractive index has distinct values for left and right, given by

.

It can be seen that a negative index will occur for one polarization if κ > √εrµr. In this case, it is not necessary that either or both εr and µr be negative for backward wave propagation.

FSS based

Frequency selective surface-based metamaterials block signals in one

waveband and pass those at another waveband. They have become an

alternative to fixed frequency metamaterials. They allow for optional

changes of frequencies in a single medium, rather than the restrictive

limitations of a fixed frequency response.

Other types

Elastic

These

metamaterials use different parameters to achieve a negative index of

refraction in materials that are not electromagnetic. Furthermore, "a

new design for elastic metamaterials that can behave either as liquids

or solids over a limited frequency range may enable new applications

based on the control of acoustic, elastic and seismic waves." They are also called mechanical metamaterials.[citation needed]

Acoustic

Acoustic metamaterials control, direct and manipulate sound in the form of sonic, infrasonic or ultrasonic waves in gases, liquids and solids. As with electromagnetic waves, sonic waves can exhibit negative refraction.

Control of sound waves is mostly accomplished through the bulk modulus β, mass density ρ

and chirality. The bulk modulus and density are analogs of permittivity

and permeability in electromagnetic metamaterials. Related to this is

the mechanics of sound wave propagation in a lattice structure. Also materials have mass and intrinsic degrees of stiffness. Together, these form a resonant system and the mechanical (sonic) resonance may be excited by appropriate sonic frequencies (for example audible pulses).

Structural

Structural metamaterials provide properties such as crushability and light weight. Using projection micro-stereolithography, microlattices can be created using forms much like trusses and girders. Materials four orders of magnitude stiffer than conventional aerogel,

but with the same density have been created. Such materials can

withstand a load of at least 160,000 times their own weight by

over-constraining the materials.

A ceramic nanotruss metamaterial can be flattened and revert to its original state.

Nonlinear

Metamaterials may be fabricated that include some form of nonlinear media, whose properties change with the power of the incident wave. Nonlinear media are essential for nonlinear optics.

Most optical materials have a relatively weak response, meaning that

their properties change by only a small amount for large changes in the

intensity of the electromagnetic field.

The local electromagnetic fields of the inclusions in nonlinear

metamaterials can be much larger than the average value of the field.

Besides, remarkable nonlinear effects have been predicted and observed

if the metamaterial effective dielectric permittivity is very small

(epsilon-near-zero media). In addition, exotic properties such as a negative refractive index, create opportunities to tailor the phase matching conditions that must be satisfied in any nonlinear optical structure.

Frequency bands

Terahertz

Terahertz metamaterials interact at terahertz frequencies, usually defined as 0.1 to 10 THz. Terahertz radiation lies at the far end of the infrared band, just after the end of the microwave band. This corresponds to millimeter and submillimeter wavelengths between the 3 mm (EHF band) and 0.03 mm (long-wavelength edge of far-infrared light).

Photonic

Photonic metamaterial interact with optical frequencies (mid-infrared). The sub-wavelength period distinguishes them from photonic band gap structures.

Tunable

Tunable metamaterials allow arbitrary adjustments to frequency

changes in the refractive index. A tunable metamaterial expands beyond

the bandwidth limitations in left-handed materials by constructing

various types of metamaterials.

Plasmonic

Plasmonic metamaterials exploit surface plasmons, which are produced from the interaction of light with metal-dielectrics. Under specific conditions, the incident light couples with the surface plasmons to create self-sustaining, propagating electromagnetic waves known as surface plasmon polaritons.

Applications

Metamaterials are under consideration for many applications. Metamaterial antennas are commercially available.

In 2007, one researcher stated that for metamaterial applications

to be realized, energy loss must be reduced, materials must be extended

into three-dimensional isotropic materials and production techniques must be industrialized.

Antennas

Metamaterial antennas are a class of antennas that use metamaterials to improve performance. Demonstrations showed that metamaterials could enhance an antenna's radiated power.

Materials that can attain negative permeability allow for properties

such as small antenna size, high directivity and tunable frequency.

Absorber

A metamaterial absorber manipulates the loss components of

metamaterials' permittivity and magnetic permeability, to absorb large

amounts of electromagnetic radiation. This is a useful feature for photodetection and solar photovoltaic applications. Loss components are also relevant in applications of negative refractive index (photonic metamaterials, antenna systems) or transformation optics (metamaterial cloaking, celestial mechanics), but often are not utilized in these applications.

Superlens

A superlens is a two or three-dimensional device that uses

metamaterials, usually with negative refraction properties, to achieve

resolution beyond the diffraction limit

(ideally, infinite resolution). Such a behaviour is enabled by the

capability of double-negative materials to yield negative phase

velocity. The diffraction limit is inherent in conventional optical

devices or lenses.

Cloaking devices

Metamaterials are a potential basis for a practical cloaking device. The proof of principle was demonstrated on October 19, 2006. No practical cloaks are publicly known to exist.

RCS (Radar Cross Section) reducing metamaterials

Conventionally, the RCS has been reduced either by Radar absorbent material

(RAM) or by purpose shaping of the targets such that the scattered

energy can be redirected away from the source. While RAMs have narrow

frequency band functionality, purpose shaping limits the aerodynamic

performance of the target. More recently, metamaterials or metasurfaces

are synthesized that can redirect the scattered energy away from the

source using either array theory or generalized Snell's law. This has led to aerodynamically favorable shapes for the targets with the reduced RCS.

Seismic protection

Seismic metamaterials counteract the adverse effects of seismic waves on man-made structures.

Sound filtering

Metamaterials

textured with nanoscale wrinkles could control sound or light signals,

such as changing a material's color or improving ultrasound resolution. Uses include nondestructive material testing, medical diagnostics and sound suppression.

The materials can be made through a high-precision, multi-layer

deposition process. The thickness of each layer can be controlled within

a fraction of a wavelength. The material is then compressed, creating

precise wrinkles whose spacing can cause scattering of selected

frequencies.

Theoretical models

All materials are made of atoms, which are dipoles. These dipoles modify light velocity by a factor n (the refractive index). In a split ring resonator the ring and wire units act as atomic dipoles: the wire acts as a ferroelectric atom, while the ring acts as an inductor L, while the open section acts as a capacitor C. The ring as a whole acts as an LC circuit.

When the electromagnetic field passes through the ring, an induced

current is created. The generated field is perpendicular to the light's

magnetic field. The magnetic resonance results in a negative

permeability; the refraction index is negative as well. (The lens is not

truly flat, since the structure's capacitance imposes a slope for the

electric induction.)

Several (mathematical) material models frequency response in DNGs. One of these is the Lorentz model, which describes electron motion in terms of a driven-damped, harmonic oscillator. The Debye relaxation model applies when the acceleration component of the Lorentz mathematical model is small compared to the other components of the equation. The Drude model applies when the restoring force component is negligible and the coupling coefficient is generally the plasma frequency. Other component distinctions call for the use of one of these models, depending on its polarity or purpose.

Three-dimensional composites of metal/non-metallic inclusions

periodically/randomly embedded in a low permittivity matrix are usually

modeled by analytical methods, including mixing formulas and

scattering-matrix based methods. The particle is modeled by either an

electric dipole parallel to the electric field or a pair of crossed

electric and magnetic dipoles parallel to the electric and magnetic

fields, respectively, of the applied wave. These dipoles are the leading

terms in the multipole series. They are the only existing ones for a

homogeneous sphere, whose polarizability can be easily obtained from the Mie scattering

coefficients. In general, this procedure is known as the "point-dipole

approximation", which is a good approximation for metamaterials

consisting of composites of electrically small spheres. Merits of these

methods include low calculation cost and mathematical simplicity.

Other first principles techniques for analyzing triply-periodic electromagnetic media may be found in Computing photonic band structure

Institutional networks

MURI

The

Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI) encompasses

dozens of Universities and a few government organizations. Participating

universities include UC Berkeley, UC Los Angeles, UC San Diego,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Imperial College in London.

The sponsors are Office of Naval Research and the Defense Advanced Research Project Agency.

MURI supports research that intersects more than one traditional

science and engineering discipline to accelerate both research and

translation to applications. As of 2009, 69 academic institutions were

expected to participate in 41 research efforts.

Metamorphose

The

Virtual Institute for Artificial Electromagnetic Materials and

Metamaterials "Metamorphose VI AISBL" is an international association to

promote artificial electromagnetic materials and metamaterials. It

organizes scientific conferences, supports specialized journals, creates

and manages research programs, provides training programs (including

PhD and training programs for industrial partners); and technology

transfer to European Industry.

.

.