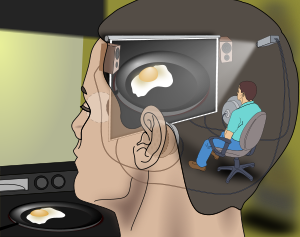

Objects experienced are represented within the mind of the observer (see Cartesian theater).

In philosophy of mind, Cartesian materialism

is the idea that at some place (or places) in the brain, there is some

set of information that directly corresponds to our conscious

experience. Contrary to its name, Cartesian materialism is not a view

that was held by or formulated by René Descartes, who subscribed rather to a form of substance dualism.

In its simplest version, Cartesian materialism might predict, for

example, that there is a specific place in the brain which would be a

coherent representation of everything we are consciously experiencing in

a given moment: what we're seeing, what we're hearing, what we're

smelling, and indeed, everything of which we are consciously aware. In

essence, Cartesian materialism claims that, somewhere in our brain,

there is a Cartesian theater

where a hypothetical observer could somehow "find" the content of

conscious experience moment by moment. In contrast, anything occurring

outside of this "privileged neural media" is nonconscious.

History

Multiple meanings

According to Marx and Engels (1845), French materialism developed from the mechanism of Descartes and the empiricism

of Locke, Hobbes, Bacon and ultimately Duns Scotus who asked "whether

matter could not think?" Natural science, in their view, owes to the

former its great success as a "Cartesian materialism", bereft of the

metaphysics of Cartesian dualism by philosophers and physicians such as Regius, Cabanis, and La Mettrie, who maintained the viability of Descartes' biological automata without recourse to immaterial cognition.

However, philosopher Daniel Dennett

uses the term to emphasize what he considers the pervasive Cartesian

notion of a centralized repository of conscious experience in the brain.

Dennett says that "Cartesian materialism is the view that there is a

crucial finish line or boundary somewhere in the brain, marking a place

where the order of arrival equals the order of 'presentation' in

experience because what happens there is what you are conscious of."

Other modern philosophers have generally used less specific

definitions. For example, O'Brien and Opie define it as the idea that

consciousness is "realized in the physical materials of the brain",

and W. Teed Rockwell defines Cartesian materialism in the following

way: "The basic dogma of Cartesian materialism is that only neural

activity in the cranium is functionally essential for the emergence of

mind."

However, although Rockwell's concept of Cartesian materialism is less

specific in a sense, it is a detailed reply to Dennett's version, not an

undeveloped predecessor. The main theme of Rockwell's book Neither Brain nor Ghost

is that the arguments Dennett uses to refute his version of Cartesian

Materialism actually support the view that the mind is an emergent

property of the entire Brain/Body/World Nexus. For Rockwell, claiming

the entire brain is identical to the mind has no better justification

than claiming that part of the brain is identical to the mind.

Dennett's version of the term is the most popular.

Cartesian dualism

Descartes believed that a human being was composed of both a material

body and an immaterial soul (or "mind"). According to Descartes, the

mind and the body could interact. The body can affect the mind; for

example, when you place your hand in a fire, the body relays sensory

information from your hand to your mind, which results in your having

the experience of pain. Similarly, the mind can affect the body; for

example, you can decide to move your hand and your muscles obey, moving

your hand as you desired.

Descartes noted that, although our two eyes independently see an

object, our conscious experience is not of two separate fields of vision

each possessing an image of the object. Rather, we seem to experience

one continuous, oval-shaped field of vision that possesses information

from both eyes which seems to have somehow been 'merged' into a single

image. (Consider in a movie, when a character looks through binoculars

and the audience is shown what he is looking at, from the character's

point of view. The image shown is never made up of two completely

separate circular images-- rather the director shows us a single

figure-eight shaped region made up of information from each eyepiece.)

Descartes noted that information from both eyes seems to have

been merged somehow before "entering" conscious perception. He also

noted similar effects for the other senses. Based on this, Descartes

hypothesized that there must be some single place in the brain where all

the sensory information is assembled, before finally being relayed to

the immaterial mind.

His best candidate for this location was the pineal gland, since

he thought it was the only part of the brain that is a single structure,

rather than one duplicated on both the left and right halves of the

brain. Descartes therefore believed that the pineal gland was the "seat

of the soul" and that any information that was to "enter" consciousness

had to pass through the pineal gland before it could enter the mind.

In his perspective, the pineal gland is the place where all information

"comes together."

Dennett's account of Cartesian materialism

At

the present time, the consensus of scientists and philosophers is to

reject dualism and its immaterial mind, for a variety of reasons.

Similarly, many other aspects of Descartes' theories have been

rejected; for example, the pineal gland turned out to be

endocrinological, rather than having a large role in information

processing.

According to Daniel Dennett, however, many scientists and

philosophers still believe, either explicitly or implicitly, in

Descartes' idea of some centralized repository where the contents of

consciousness are merged and assembled, a place he calls the Cartesian theater.

In his book Consciousness Explained (1991), Dennett writes:

- Let's call the idea of such a centered locus in the brain Cartesian materialism, since it's the view you arrive at when you discard Descartes' dualism but fail to discard the imagery of a central (but material) Theater where it "all comes together."

Although this central repository is often called a "place" or a

"location", Dennett is quick to clarify that Cartesian materialism's

"centered locus" need not be anatomically defined-- such a locus might

consists of a network of diverse regions.

Dennett's arguments against Cartesian materialism

In Consciousness Explained, Dennett offers several lines of evidence to dispute the idea of Cartesian materialism.

No exact place

One

argument against Cartesian materialism is that most neuroscientists

have discounted the idea of a single brain area where all information

"comes together". Instead, information seemed to be stored and

processed in a variety of disparate neural structures. For example,

once information from the eyes reaches the visual cortex, it is analyzed

by a variety of overlapping feature maps, each detecting a particular

aspect, but a central location where this information is merged back

together to re-represent it has not been found.

Dennett argues that there would be no point to such a merger since all

the analysis has already been performed and there is no homunculus who

would benefit from a reconstructed composite.

Timing anomalies of conscious experience

Another

argument against Cartesian materialism is inspired by the results of

several scientific experiments in the fields of psychology and

neuroscience. In experiments that demonstrate the Color Phi phenomenon

and the metacontrast effect, two stimuli are rapidly flashed on a

screen, one after the other. Amazingly, the second stimulus can, in

some cases, actually affect the perception of the first stimulus. In

other experiments conducted by Benjamin Libet,

two electrical stimulations are delivered, one after another, to a

conscious subject. Under some conditions, subjects report having felt

the second stimulation before they felt the first stimulation.

These experiments call into question the idea that brain states

are directly translatable into the contents of consciousness. How can

the second stimuli be 'projected backwards in time', such that it can

affect the perception of things that occurred before the second stimulus

was even administered?

Two attempted explanations

Two

different types of explanations have been offered in response to the

timing anomalies. One is that perhaps sensory information is assembled

into a buffer

before being passed on to consciousness after a substantial time delay.

Since consciousness occurs only after a time lag, the incoming second

stimulus would have time to affect the stored information about the

first stimulus. In this view, subjects correctly remember their having

had inaccurate experiences. Dennett calls this the "Stalinesque

Explanation" (after the Stalinist Soviet Union's show trials that presented manufactured evidence to an unwitting jury).

A second explanation for the timing takes the opposite tack.

Perhaps the subjects, contrary to their own reports, initially

experienced the first stimulus as being prior to and untainted by the

second stimulus. However, when subjects were later asked to recall what

their experiences had been, they found that their memories of the first

stimulus had been tainted by the second stimulus. Therefore, they

inaccurately report experiences that never actually occurred. In this

view, subjects have accurate initial experiences, but inaccurately

remember them. Dennett calls this view the "Orwellian Explanation",

after George Orwell's novel 1984, in which a totalitarian government frequently rewrites history to suit its purposes.

How are we to choose which of these two explanations is the

correct one? Both explanations seem to adequately explain the given

data, both seem to make the same predictions. Dennett sees no principled

basis for choosing either of the explanations, so he rejects their

common assumption of a theater. He says:

We can suppose, both theorists have exactly the same theory of what happens in your brain; they agree about just where and when in the brain the mistaken content enters the causal pathways; they just disagree about whether that location is to be deemed pre-experiential or post-experiential. [...] They even agree about how it ought to "feel" to subjects: Subjects should be unable to tell the difference between misbegotten experiences and immediately misremembered experiences.

Dennett's conclusions

Dennett's argument has the following basic structure:

- If Cartesian materialism were true and there really was a special brain area (or areas) that stored the contents of conscious experience, then it should be possible to ascertain exactly when something enters conscious experience.

- It is impossible, even in theory, to ever precisely determine when something enters conscious experience.

- Therefore, Cartesian materialism is false.

According to Dennett, the debate between Stalinesque and Orwellian

explanations is unresolvable — no amount of scientific information could

ever answer the question. Dennett therefore argues (in accord with the

philosophical doctrine of verificationism)

that, since the differences between the two explanations are

unresolvable, the point of disagreement is logically meaningless so both

explanations are mistaken.

Dennett feels that the insistence on a place where 'it all comes together' (the Cartesian Theater)

is fundamentally flawed, and therefore that Cartesian materialism is

false. Dennett's view is that "there is no single, definitive 'stream of

consciousness,' because there is no central Headquarters, no Cartesian

Theatre where 'it all comes together'".

To avoid the perceived shortcomings of Cartesian materialism, Dennett instead proposes the multiple drafts model — a model of consciousness which lacks a central Cartesian theater.

Replies and objections to Dennett and his arguments

A philosophy without adherents?

Perhaps the primary objection to Dennett's use of the term Cartesian materialism is that

it is a philosophy without adherents. In this view, Cartesian materialism is essentially a "Straw Man" — an argument explicitly constructed just so it can be refuted:

The now standard response to Dennett’s project is that he has picked a fight with a straw man. Cartesian materialism, it is alleged, is an impossibly naive account of phenomenal consciousness held by no one currently working in cognitive science or the philosophy of mind. Consequently, whatever the effectiveness of Dennett’s demolition job, it is fundamentally misdirected (see, e.g., Block, 1993, 1995; Shoemaker, 1993; and Tye, 1993).

It is a point of intense debate as to how many philosophers and

scientists even accept Cartesian materialism. On the one hand, some say

that this view is "held by no one currently working in cognitive science

or the philosophy of mind"

or insist that they "know of no one who endorses it." (Michael Tye) On

the other hand, some say that Cartesian materialism "informs virtually

all research on mind and brain, explicitly and implicitly" (Antonio

Damasio) or argue that the common "commitment to qualia or 'phenomenal

seemings'" entails an implicit commitment to Cartesian materialism that

becomes explicit when they "work out a theory of consciousness in

sufficient detail".

Dennett suggests that the Cartesian materialism, though rejected

by many philosophers, still colors people's thinking. He writes:

- Perhaps no one today explicitly endorses Cartesian materialism. Many theorists would insist that they have explicitly rejected such an obviously bad idea. But as we shall see, the persuasive imagery of a Cartesian theater keeps coming back to haunt us — laypeople and scientists alike — even after its ghostly dualism has been denounced and exorcised.

Replies from dualism

Many philosophers question Dennett's immediate rejection of dualism (dismissing it after only a few pages of argument in Consciousness Explained), pointing to a variety of reasons that people often find dualism to be a compelling view.

To proponents of dualism, mental events have a certain subjective

quality to them, whereas physical events obviously do not. That is, for

example, what a burned finger feels like, what sky blue looks like,

what nice music sounds like, and so on. There is something that it's

like to feel pain, to see a familiar shade of blue, and so on; These

sensations independent of behavior are known as qualia, and the philosophical problem posed by their alleged existence is called the hard problem of consciousness by Chalmers.

Dualists argue that Dennett does not explain these phenomena, so much as ignore them. Indeed, the title of Dennett's book Consciousness Explained is often lampooned by critics, who call the book Consciousness Explained Away or even Consciousness Ignored.

Replies from Cartesian materialists

Some philosophers have actively accepted the moniker of Cartesian Materialists, and are not convinced by Dennett's arguments.

O'Brien and Opie (1999) embrace Cartesian materialism, arguing

against Dennett's claim that the onset of phenomenal experience in the

brain cannot in principle be precisely determined, and offering what

they consider to be a way to accommodate Phi phenomenon within the Cartesian materialist paradigm.

Block has described an alternative called "Cartesian Modularism"

in which the contents of conscious experience are distributed in the

brain.

Replies from neuroscience

Despite

Dennett's insistence that there are no special brain areas that store

the contents of consciousness, many neuroscientists reject this

assertion. Indeed, what separates conscious information from

unconscious information remains a question of interest, and how

information from disparate brain regions are assembled into a coherent

whole (the Binding problem) remains a question which is actively investigated. Recently Global Workspace Theory has argued that perhaps the brain does possess some universally accessible "workspace".

Another criticism comes from investigation into the human visual

system. Although both eyes each have a blind spot, conscious visual

experience does not subjectively seem to have any holes in it. Some

scientists and philosophers had argued, based on subjective reports,

that perhaps the brain somehow "fills in" the holes, based upon adjacent

visual information. Dennett had powerfully argued that such "filling

in" was unnecessary, based on his objections to a Cartesian theater.

Ultimately, however, studies have confirmed that the visual cortex does

perform a very complex "filling in" process.

The impact of this is itself controversial. Some assume that

this is a devastating blow against Dennett, while others have argued

that this in no way confirms Cartesian materialism or refutes the

multiple drafts model, and that Dennett is fundamentally right even if

he's mistaken about this detail.