Eliminativists

argue that modern belief in the existence of mental phenomena is

analogous to the ancient belief in obsolete theories such as the geocentric model of the universe.

Eliminative materialism (also called eliminativism) is the claim that people's common-sense understanding of the mind (or folk psychology) is false and that certain classes of mental states that most people believe in do not exist. It is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since they are poorly defined. Rather, they argue that psychological concepts of behavior and experience should be judged by how well they reduce to the biological level. Other versions entail the non-existence of conscious mental states such as pain and visual perceptions.

Eliminativism about a class of entities is the view that that class of entities does not exist. For example, materialism tends to be eliminativist about the soul; modern chemists are eliminativist about phlogiston; and modern physicists are eliminativist about the existence of luminiferous aether. Eliminative materialism

is the relatively new (1960s–1970s) idea that certain classes of mental

entities that common sense takes for granted, such as beliefs, desires,

and the subjective sensation of pain, do not exist. The most common versions are eliminativism about propositional attitudes, as expressed by Paul and Patricia Churchland, and eliminativism about qualia (subjective interpretations about particular instances of subjective experience), as expressed by Daniel Dennett and Georges Rey. These philosophers often appeal to an introspection illusion.

In the context of materialist understandings of psychology, eliminativism stands in opposition to reductive materialism which argues that mental states as conventionally understood do exist, and that they directly correspond to the physical state of the nervous system. An intermediate position is revisionary materialism, which will often argue that the mental state in question will prove to be somewhat reducible to physical phenomena—with some changes needed to the common sense concept.

Since eliminative materialism claims that future research will

fail to find a neuronal basis for various mental phenomena, it must

necessarily wait for science to progress further. One might question the

position on these grounds, but other philosophers like Churchland argue

that eliminativism is often necessary in order to open the minds of

thinkers to new evidence and better explanations.

Overview

Various

arguments have been put forth both for and against eliminative

materialism over the last forty years. Most of the arguments in favor of

the view are based on the assumption that people's commonsense view of

the mind is actually an implicit theory. It is to be compared and

contrasted with other scientific theories in its explanatory success,

accuracy, and ability to allow people to make correct predictions about

the future. Eliminativists argue that, based on these and other

criteria, commonsense "folk" psychology has failed and will eventually

need to be replaced with explanations derived from the neurosciences.

These philosophers therefore tend to emphasize the importance of

neuroscientific research as well as developments in artificial intelligence to sustain their thesis.

Philosophers who argue against eliminativism may take several approaches. Simulation theorists, like Robert Gordon and Alvin Goldman

argue that folk psychology is not a theory, but rather depends on

internal simulation of others, and therefore is not subject to

falsification in the same way that theories are. Jerry Fodor, among others,

argues that folk psychology is, in fact, a successful (even

indispensable) theory. Another view is that eliminativism assumes the

existence of the beliefs and other entities it seeks to "eliminate" and

is thus self-refuting.

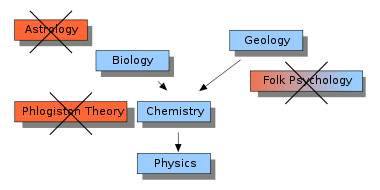

Schematic overview: Eliminativists suggest that some sciences can be reduced (blue), but that theories that are in principle irreducible will eventually be eliminated (orange).

Eliminativism maintains that the common-sense understanding of the mind is mistaken, and that the neurosciences

will one day reveal that the mental states that are talked about in

everyday discourse, using words such as "intend", "believe", "desire",

and "love", do not refer to anything real. Because of the inadequacy of

natural languages, people mistakenly think that they have such beliefs

and desires. Some eliminativists, such as Frank Jackson, claim that consciousness does not exist except as an epiphenomenon of brain function; others, such as Georges Rey, claim that the concept will eventually be eliminated as neuroscience progresses.

Consciousness and folk psychology are separate issues and it is

possible to take an eliminative stance on one but not the other. The roots of eliminativism go back to the writings of Wilfred Sellars, W.V. Quine, Paul Feyerabend, and Richard Rorty. The term "eliminative materialism" was first introduced by James Cornman in 1968 while describing a version of physicalism endorsed by Rorty. The later Ludwig Wittgenstein

was also an important inspiration for eliminativism, particularly with

his attack on "private objects" as "grammatical fictions".

Early eliminativists such as Rorty and Feyerabend often confused

two different notions of the sort of elimination that the term

"eliminative materialism" entailed. On the one hand, they claimed, the cognitive sciences

that will ultimately give people a correct account of the workings of

the mind will not employ terms that refer to common-sense mental states

like beliefs and desires; these states will not be part of the ontology of a mature cognitive science. But critics immediately countered that this view was indistinguishable from the identity theory of mind. Quine himself wondered what exactly was so eliminative about eliminative materialism after all:

| “ | Is physicalism a repudiation of mental objects after all, or a theory of them? Does it repudiate the mental state of pain or anger in favor of its physical concomitant, or does it identify the mental state with a state of the physical organism (and so a state of the physical organism with the mental state)? | ” |

On the other hand, the same philosophers also claimed that

common-sense mental states simply do not exist. But critics pointed out

that eliminativists could not have it both ways: either mental states

exist and will ultimately be explained in terms of lower-level

neurophysiological processes or they do not.

Modern eliminativists have much more clearly expressed the view that

mental phenomena simply do not exist and will eventually be eliminated

from people's thinking about the brain in the same way that demons have

been eliminated from people's thinking about mental illness and

psychopathology.

While it was a minority view in the 1960s, eliminative materialism gained prominence and acceptance during the 1980s. Proponents of this view, such as B.F. Skinner, often made parallels to previous superseded scientific theories (such as that of the four humours, the phlogiston theory of combustion, and the vital force

theory of life) that have all been successfully eliminated in

attempting to establish their thesis about the nature of the mental. In

these cases, science has not produced more detailed versions or

reductions of these theories, but rejected them altogether as obsolete. Radical behaviorists, such as Skinner, argued that folk psychology is already obsolete and should be replaced by descriptions of histories of reinforcement and punishment. Such views were eventually abandoned. Patricia and Paul Churchland argued that folk psychology will be gradually replaced as neuroscience matures.

Eliminativism is not only motivated by philosophical

considerations, but is also a prediction about what form future

scientific theories will take. Eliminativist philosophers therefore tend

to be concerned with the data coming from the relevant brain and cognitive sciences.

In addition, because eliminativism is essentially predictive in

nature, different theorists can, and often do, make different

predictions about which aspects of folk psychology will be eliminated

from folk psychological vocabulary. None of these philosophers are

eliminativists "tout court".

Today, the eliminativist view is most closely associated with the philosophers Paul and Patricia Churchland, who deny the existence of propositional attitudes (a subclass of intentional states), and with Daniel Dennett, who is generally considered to be an eliminativist about qualia

and phenomenal aspects of consciousness. One way to summarize the

difference between the Churchlands's views and Dennett's view is that

the Churchlands are eliminativists when it comes to propositional

attitudes, but reductionists

concerning qualia, while Dennett is an anti-reductionist with respect

to propositional attitudes, and an eliminativist concerning qualia.

Arguments for eliminativism

Problems with folk theories

Eliminativists such as Paul and Patricia Churchland argue that folk psychology

is a fully developed but non-formalized theory of human behavior. It is

used to explain and make predictions about human mental states and

behavior. This view is often referred to as the theory of mind or just simply theory-theory, for it is a theory which theorizes the existence of an unacknowledged theory. As a theory

in the scientific sense, eliminativists maintain, folk psychology needs

to be evaluated on the basis of its predictive power and explanatory

success as a research program for the investigation of the mind/brain.

Such eliminativists have developed different arguments to show

that folk psychology is a seriously mistaken theory and needs to be

abolished. They argue that folk psychology excludes from its purview or

has traditionally been mistaken about many important mental phenomena

that can, and are, being examined and explained by modern neurosciences. Some examples are dreaming, consciousness, mental disorders, learning processes, and memory

abilities. Furthermore, they argue, folk psychology's development in

the last 2,500 years has not been significant and it is therefore a

stagnating theory. The ancient Greeks

already had a folk psychology comparable to modern views. But in

contrast to this lack of development, the neurosciences are a rapidly

progressing science complex that, in their view, can explain many cognitive processes that folk psychology cannot.

Folk psychology retains characteristics of now obsolete theories

or legends from the past. Ancient societies tried to explain the

physical mysteries of nature

by ascribing mental conditions to them in such statements as "the sea

is angry". Gradually, these everyday folk psychological explanations

were replaced by more efficient scientific

descriptions. Today, eliminativists argue, there is no reason not to

accept an effective scientific account of people's cognitive abilities.

If such an explanation existed, then there would be no need for

folk-psychological explanations of behavior, and the latter would be

eliminated the same way as the mythological explanations the ancients used.

Another line of argument is the meta-induction based on what

eliminativists view as the disastrous historical record of folk theories

in general. Ancient pre-scientific "theories" of folk biology, folk

physics, and folk cosmology have all proven to be radically wrong.

Eliminativists argue the same in the case of folk psychology. There

seems no logical basis, to the eliminativist, for making an exception

just because folk psychology has lasted longer and is more intuitive or

instinctively plausible than the other folk theories.

Indeed, the eliminativists warn, considerations of intuitive

plausibility may be precisely the result of the deeply entrenched nature

in society of folk psychology itself. It may be that people's beliefs

and other such states are as theory-laden as external perceptions and

hence intuitions will tend to be biased in favor of them.

Specific problems with folk psychology

Much of folk psychology involves the attribution of intentional states (or more specifically as a subclass, propositional attitudes).

Eliminativists point out that these states are generally ascribed

syntactic and semantic properties. An example of this is the language of thought

hypothesis, which attributes a discrete, combinatorial syntax and other

linguistic properties to these mental phenomena. Eliminativists argue

that such discrete and combinatorial characteristics have no place in

the neurosciences, which speak of action potentials, spiking frequencies,

and other effects which are continuous and distributed in nature.

Hence, the syntactic structures which are assumed by folk psychology can

have no place in such a structure as the brain.

Against this there have been two responses. On the one hand, there are

philosophers who deny that mental states are linguistic in nature and

see this as a straw man argument. The other view is represented by those who subscribe to "a language of thought". They assert that the mental states can be multiply realized and that functional characterizations are just higher-level characterizations of what's happening at the physical level.

It has also been argued against folk psychology that the

intentionality of mental states like belief imply that they have

semantic qualities. Specifically, their meaning is determined by the

things that they are about in the external world. This makes it

difficult to explain how they can play the causal roles that they are

supposed to in cognitive processes.

In recent years, this latter argument has been fortified by the theory of connectionism.

Many connectionist models of the brain have been developed in which the

processes of language learning and other forms of representation are

highly distributed and parallel. This would tend to indicate that there

is no need for such discrete and semantically endowed entities as

beliefs and desires.

Arguments against eliminativism

Intuitive reservations

The

thesis of eliminativism seems to be so obviously wrong to many critics,

under the claim that people know immediately and indubitably that they

have minds, that argumentation seems unnecessary. This sort of intuition

pumping is illustrated by asking what happens when one asks oneself

honestly if one has mental states. Eliminativists object to such a rebuttal of their position by claiming that intuitions often are mistaken. Analogies from the history of science are frequently invoked to buttress this observation: it may appear obvious that the sun travels around the earth,

for example, but for all its apparent obviousness this conception was

proved wrong nevertheless. Similarly, it may appear obvious that apart

from neural events there are also mental conditions. Nevertheless, this

could equally turn out to be false.

But even if one accepts the susceptibility to error of people's

intuitions, the objection can be reformulated: if the existence of

mental conditions seems perfectly obvious and is central in people's

conception of the world, then enormously strong arguments are needed in

order to successfully deny the existence of mental conditions.

Furthermore, these arguments, to be consistent, need to be formulated in

a way which does not pre-suppose the existence of entities like "mental

states", "logical arguments", and "ideas", otherwise they are self-contradictory.

Those who accept this objection say that the arguments in favor of

eliminativism are far too weak to establish such a radical claim;

therefore there is no reason to believe in eliminativism.

Self-refutation

Some philosophers, such as Paul Boghossian, have attempted to show that eliminativism is in some sense self-refuting,

since the theory itself presupposes the existence of mental phenomena.

If eliminativism is true, then the eliminativist must permit an intentional property like truth,

supposing that in order to assert something one must believe it. Hence,

for eliminativism to be asserted as a thesis, the eliminativist must

believe that it is true; if that is the case, then there are beliefs and

the eliminativist claim is false.

Georges Rey and Michael Devitt reply to this objection by invoking deflationary semantic theories that avoid analyzing predicates

like "x is true" as expressing a real property. They are construed,

instead, as logical devices so that asserting that a sentence is true is

just a quoted way of asserting the sentence itself. To say, "'God

exists' is true" is just to say, "God exists". This way, Rey and Devitt

argue, insofar as dispositional replacements of "claims" and

deflationary accounts of "true" are coherent, eliminativism is not

self-refuting.

Qualia

Another problem for the eliminativist is the consideration that human beings undergo subjective experiences and, hence, their conscious mental states have qualia.

Since qualia are generally regarded as characteristics of mental

states, their existence does not seem to be compatible with

eliminativism. Eliminativists, such as Daniel Dennett and Georges Rey, respond by rejecting qualia.

This is seen to be problematic to opponents of eliminativists, since

many claim that the existence of qualia seems perfectly obvious. Many

philosophers consider the "elimination" of qualia implausible, if not

incomprehensible. They assert that, for instance, the existence of pain

is simply beyond denial.

Admitting that the existence of qualia seems obvious, Dennett

nevertheless states that "qualia" is a theoretical term from an outdated

metaphysics stemming from Cartesian

intuitions. He argues that a precise analysis shows that the term is in

the long run empty and full of contradictions. The eliminativist's

claim with respect to qualia is that there is no unbiased evidence for

such experiences when regarded as something more than propositional attitudes. In other words, they do not deny that pain exists, but that it exists independently of its effect on behavior. Influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein's Philosophical Investigations, Dennett and Rey have defended eliminativism about qualia, even when other portions of the mental are accepted.

Efficacy of folk psychology

Some philosophers argue that folk psychology is a quite successful theory.

Simulation theorists doubt that people's understanding of the mental

can be explained in terms of a theory at all. Rather they argue that

people's understanding of others is based on internal simulations of how

they would act and respond in similar situations. Jerry Fodor

is one of the objectors that believes in folk psychology's success as a

theory, because it makes for an effective way of communication in

everyday life that can be implemented with few words. Such an

effectiveness could never be achieved with a complex neuroscientific

terminology.