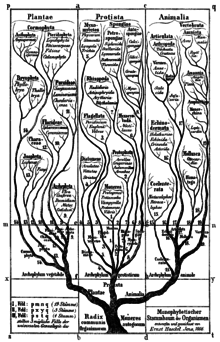

Evolutionary progress as a tree of life. Ernst Haeckel, 1866

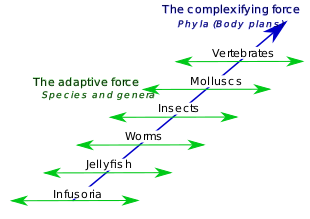

Lamarck's two-factor theory involves 1) a complexifying force that drives animal body plans towards higher levels (orthogenesis) creating a ladder of phyla, and 2) an adaptive force that causes animals with a given body plan to adapt to circumstances (use and disuse, inheritance of acquired characteristics), creating a diversity of species and genera. Popular views of Lamarckism only consider an aspect of the adaptive force.

Orthogenesis, also known as orthogenetic evolution, progressive evolution, evolutionary progress, or progressionism, is the biological hypothesis that organisms have an innate tendency to evolve in a definite direction towards some goal (teleology) due to some internal mechanism or "driving force". According to the theory, the largest-scale trends in evolution have an absolute goal such as increasing biological complexity. Prominent historical figures who have championed some form of evolutionary progress include Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, and Henri Bergson.

The term orthogenesis was introduced by Wilhelm Haacke in 1893 and popularized by Theodor Eimer five years later. Proponents of orthogenesis had rejected the theory of natural selection as the organizing mechanism in evolution for a rectilinear model of directed evolution. With the emergence of the modern synthesis, in which genetics was integrated with evolution, orthogenesis and other alternatives to Darwinism

were largely abandoned by biologists, but the notion that evolution

represents progress is still widely shared. The evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr made the term effectively taboo in the journal Nature in 1948, by stating that it implied "some supernatural force". The American paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson (1953) attacked orthogenesis, linking it with vitalism by describing it as "the mysterious inner force". Modern supporters include E. O. Wilson and Simon Conway Morris, while museum displays and textbook illustrations continue to give the impression of progress in evolution.

The philosopher of biology Michael Ruse notes that in popular culture evolution and progress are synonyms, while the unintentionally misleading image of the March of Progress, from apes to modern humans, has been widely imitated.

Definition

The term orthogenesis (from Ancient Greek ὀρθός orthós, "straight",

and γένεσις génesis, "origin") was first used by the biologist Wilhelm Haacke in 1893. Theodor Eimer

was the first to give the word a definition; he defined orthogenesis as

"the general law according to which evolutionary development takes

place in a noticeable direction, above all in specialized groups".

In 1922, the zoologist Michael F. Guyer wrote:

[Orthogenesis] has meant many different things to many different people, ranging from a mystical inner perfecting principle, to merely a general trend in development due to the natural constitutional restrictions of the germinal materials, or to the physical limitations imposed by a narrow environment. In most modern statements of the theory, the idea of continuous and progressive change in one or more characters, due according to some to internal factors, according to others to external causes-evolution in a "straight line" seems to be the central idea.

According to Susan R. Schrepfer in 1983:

Orthogenesis meant literally "straight origins", or "straight line evolution". The term varied in meaning from the overtly vitalistic and theological to the mechanical. It ranged from theories of mystical forces to mere descriptions of a general trend in development due to natural limitations of either the germinal material or the environment ... By 1910, however most who subscribed to orthogenesis hypothesized some physical rather than metaphysical determinant of orderly change.

In 1988, Francisco J. Ayala

defined progress as "systematic change in a feature belonging to all

the members of a sequence in such a way that posterior members of the

sequence exhibit an improvement of that feature". He argued that there

are two elements in this definition, directional change and improvement

according to some standard. Whether a directional change constitutes an

improvement is not a scientific question; therefore Ayala suggested that

science should focus on the question of whether there is directional

change, without regard to whether the change is "improvement". This may be compared to Stephen Jay Gould's suggestion of "replacing the idea of progress with an operational notion of directionality".

In 1989, Peter J. Bowler defined orthogenesis as:

Literally, the term means evolution in a straight line, generally assumed to be evolution that is held to a regular course by forces internal to the organism. Orthogenesis assumes that variation is not random but is directed towards fixed goals. Selection is thus powerless, and the species is carried automatically in the direction marked out by internal factors controlling variation.

In 1996, Michael Ruse

defined orthogenesis as "the view that evolution has a kind of momentum

of its own that carries organisms along certain tracks".

History

The medieval great chain of being as a staircase, implying the possibility of progress: Ramon Lull's Ladder of Ascent and Descent of the Mind, 1305

Medieval

The possibility of progress is embedded in the mediaeval great chain of being, with a linear sequence of forms from lowest to highest. The concept, indeed, had its roots in Aristotle's biology,

from insects that produced only a grub, to fish that laid eggs, and on

up to animals with blood and live birth. The mediaeval chain, as in Ramon Lull's Ladder of Ascent and Descent of the Mind, 1305, added steps or levels above humans, with orders of angels reaching up to God at the top.

Pre-Darwinian

The orthogenesis hypothesis had a significant following in the 19th century when evolutionary mechanisms such as Lamarckism were being proposed. The French zoologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck

(1744–1829) himself accepted the idea, and it had a central role in his

theory of inheritance of acquired characteristics, the hypothesized

mechanism of which resembled the "mysterious inner force" of

orthogenesis. Orthogenesis was particularly accepted by paleontologists who saw in their fossils a directional change, and in invertebrate paleontology

thought there was a gradual and constant directional change. Those who

accepted orthogenesis in this way, however, did not necessarily accept

that the mechanism that drove orthogenesis was teleological (had a definite goal). Charles Darwin

himself rarely used the term "evolution" now so commonly used to

describe his theory, because the term was strongly associated with

orthogenesis, as had been common usage since at least 1647.

With Darwin

Reviewing Darwin's Origin of Species, Karl Ernst von Baer argued for a directed force guiding evolution.

Ruse observed that "Progress (sic, his capitalisation) became essentially a nineteenth-century belief. It gave meaning to life—it offered inspiration—after the collapse [with Malthus's pessimism and the shock of the French revolution] of the foundations of the past."

The Russian biologist Karl Ernst von Baer (1792–1876) argued for an orthogenetic force in nature, reasoning in a review of Darwin's 1859 On the Origin of Species that "Forces which are not directed—so-called blind forces—can never produce order."

In 1864, the Swiss anatomist Albert von Kölliker (1817–1905) presented his orthogenetic theory, heterogenesis, arguing for wholly separate lines of descent with no common ancestor.

In 1884, the Swiss botanist Carl Nägeli (1817–1891) proposed a version of orthogenesis involving an "inner perfecting principle". Gregor Mendel died that same year; Nägeli, who proposed that an "idioplasm" transmitted inherited characteristics, dissuaded Mendel from continuing to work on plant genetics. According to Nägeli many evolutionary developments were nonadaptive and variation was internally programmed. Charles Darwin

saw this as a serious challenge, replying that "There must be some

efficient cause for each slight individual difference", but was unable

to provide a specific answer without knowledge of genetics. Further,

Darwin was himself somewhat progressionist, believing for example that

"Man" was "higher" than the barnacles he studied.

Darwin indeed wrote in his 1859 Origin of Species:

The inhabitants of each successive period in the world's history have beaten their predecessors in the race for life, and are, insofar, higher in the scale of nature; and this may account for that vague yet ill-defined sentiment, felt by many paleontologists, that organization on the whole has progressed. [Chapter 10]

As all the living forms of life are the lineal descendants of those which lived long before the Silurian epoch, we may feel certain that the ordinary succession by generation has never once been broken, and that no cataclysm has desolated the whole world. Hence we may look with some confidence to a secure future of equally inappreciable length. And as natural selection works solely by and for the good of each being, all corporeal and mental endowments will tend to progress towards perfection. [Chapter 14]

Henry Fairfield Osborn's 1934 version of orthogenesis, aristogenesis, argued that aristogenes, not mutation or natural selection, created all novelty. Osborn supposed that the horns of Titanotheres evolved into a baroque form, way beyond the adaptive optimum.

In 1898, after studying butterfly coloration, Theodor Eimer (1843–1898) introduced the term orthogenesis with a widely read book, On Orthogenesis: And the Impotence of Natural Selection in Species Formation. Eimer claimed there were trends in evolution with no adaptive significance that would be difficult to explain by natural selection. To supporters of orthogenesis, in some cases species could be led by such trends to extinction. Eimer linked orthogenesis to neo-Lamarckism in his 1890 book Organic Evolution as the Result of the Inheritance of Acquired Characteristics According to the Laws of Organic Growth. He used examples such as the evolution of the horse

to argue that evolution had proceeded in a regular single direction

that was difficult to explain by random variation. Gould described Eimer

as a materialist who rejected any vitalist or teleological

approach to orthogenesis, arguing that Eimer's criticism of natural

selection was common amongst many evolutionists of his generation; they

were searching for alternative mechanisms, as they had come to believe

that natural selection could not create new species.

Nineteenth and twentieth century

Numerous versions of orthogenesis have been proposed.

Debate centred on whether such theories were scientific, or whether

orthogenesis was inherently vitalistic or essentially theological. For example, biologists such as Maynard M. Metcalf (1914), John Merle Coulter (1915), David Starr Jordan (1920) and Charles B. Lipman (1922) claimed evidence for orthogenesis in bacteria, fish populations and plants.

In 1950, the German paleontologist Otto Schindewolf argued that variation tends to move in a predetermined direction. He believed this was purely mechanistic, denying any kind of vitalism, but that evolution occurs due to a periodic cycle of evolutionary processes dictated by factors internal to the organism.

In 1964 George Gaylord Simpson

argued that orthogenetic theories such as those promulgated by Du Noüy

and Sinnott were essentially theology rather than biology.

Though evolution is not progressive, it does sometimes proceed in

a linear way, reinforcing characteristics in certain lineages, but such

examples are entirely consistent with the modern neo-Darwinian theory

of evolution. These examples have sometimes been referred to as orthoselection

but are not strictly orthogenetic, and simply appear as linear and

constant changes because of environmental and molecular constraints on

the direction of change. The term orthoselection was first used by Ludwig Hermann Plate, and was incorporated into the modern synthesis by Julian Huxley and Bernard Rensch.

Recent work has supported the mechanism and existence of mutation-biased adaptation, meaning that limited local orthogenesis is now seen as possible.

Theories

For the columns for other philosophies of evolution (i.e., combined

theories including any of Lamarckism, Mutationism, Natural selection,

and Vitalism), "yes" means that person definitely supports the theory;

"no" means explicit opposition to the theory; a blank means the matter

is apparently not discussed, not part of the theory.

| Author | Title | Field | Date | Lam. | Mut. | NS. | Vit. | Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lamarck | Inherent progressive tendency | Zoology | 1809 | yes | In his Philosophie Zoologique, inherent progressive tendency drives organisms continuously towards greater complexity, in separate lineages (phyla), no extinction. ("Lamarckism", use and disuse, and inheritance of acquired characteristics, was a secondary aspect of this, an adaptive force creating species within a phylum.) | |||

| Baer | Purposeful creation | Embryology | 1859 | "Forces which are not directed—so-called blind forces—can never produce order." | ||||

| Kölliker | Heterogenesis | Anatomy | 1864 | yes | Wholly separate lines of descent with no common ancestor | |||

| Cope | Law of acceleration | Paleontology | 1868 | yes | Combined orthogenetic constraints with Lamarckian use and disuse. "On the Origin of Genera"; See also Cope's rule (linear increase in size of species) | |||

| Nägeli | Inner perfecting principle | Botany | 1884 | yes | no | An "idioplasm" transmitted inherited characteristics; many evolutionary developments nonadaptive; variation internally programmed. | ||

| Spencer | Progressionism 'The Development Hypothesis' |

Social theory | 1852 | Yes | Cultural value of progress; "Spencer has no rivals when it comes to open, flagrant connections of social Progress with evolutionary progress."—Michael Ruse | |||

| Darwin | (concept of higher and lower species), Pangenesis | Evolution | 1859 | yes | yes | Origin of Species is somewhat progressionist, e.g. man higher than animals, alongside natural selection Pangenesis theory of inheritance by gemmules from all over body was Lamarckian: parents could pass on traits acquired in lifetime. | ||

| Haacke | Orthogenesis | Zoology | 1893 | yes | Accompanied by epimorphism, a tendency to increasing perfection | |||

| Eimer | Orthogenesis | Zoology | 1898 | no | On Orthogenesis: And the Impotence of Natural Selection in Species Formation: trends in evolution with no adaptive significance, claimed hard to explain by natural selection. | |||

| Bergson | Elan vital | Philosophy | 1907 | yes | Creative Evolution | |||

| Przibram | Apogenesis | Embryology | 1910 | |||||

| Plate | Orthoselection or Old-Darwinism | Zoology | 1913 | yes | yes | yes | Combined theory | |

| Rosa | Hologenesis | Zoology | 1918 | yes | Hologenesis: a New Theory of Evolution and the Geographical Distribution of Living Beings | |||

| Whitman | Orthogenesis | Zoology | 1919 | no | no | no | Orthogenetic Evolution in Pigeons posthumous | |

| Berg | Nomogenesis | Zoology | 1926 | no | yes | no | Chemical forces direct evolution, leading to humans | |

| Abel | Trägheitsgesetz (the law of inertia) | Paleontology | 1928 | based on Dollo's law of irreversibility of evolution (which can be explained without orthogenesis as a statistical improbability that a path should be exactly reversed) | ||||

| Lwoff | Physiological degradation | Physiology | 1930s–1940s | yes | Directed loss of functions in microorganisms | |||

| Beurlen | Orthogenesis | Paleontology | 1930 | no | no | Start is random metakinesis, generating variety; then palingenesis (in Beurlen's sense, repeating developmental pathway of ancestors) as mechanism for orthogenesis | ||

| Victor Jollos | Directed mutation | Protozoology, Zoology | 1931 | yes | Combined orthogenesis with Lamarckism (inheriting acquired characteristics after heat shock as dauermodifications, passed on by plasmatic inheritance in the cytoplasm) | |||

| Osborn | Aristogenesis | Paleontology | 1934 | yes | no | no | ||

| Willis | Differentiation (orthogenesis) | Botany | 1942 | yes | a force "working upon some definite law that we do not yet comprehend", compromise between special creation and natural selection, driven by large mutations involving chromosome alterations | |||

| Noüy | Telefinalism | Biophysics | 1947 | yes | In book Human Destiny, essentially religious | |||

| Vandel | Organicism | Zoology | 1949 | L'Homme et L'Evolution | ||||

| Sinnott | Telism | Botany | 1950 | yes | In book Cell and Psyche, essentially religious | |||

| Schindewolf | Typostrophism | Paleontology | 1950 | yes | Basic Questions in Paleontology: Geologic Time, Organic Evolution and Biological Systematics; evolution due to periodic cycle of processes dictated by factors internal to organism. | |||

| Teilhard de Chardin | Directed additivity, Noogenesis Omega principle |

Paleontology Mysticism |

1959 | yes | The Phenomenon of Man posthumous; combined orthogenesis with non-material vitalist directive force aiming for a supposed "Omega Point" with creation of consciousness. Noosphere concept from Vladimir Vernadsky. Censured by Gaylord Simpson for nonscientific spiritualistic "doubletalk". | |||

| Croizat | Biological synthesis Panbiogeography |

Botany | 1964 | mechanistic, caused by developmental constraints or phylogenetic constraints |

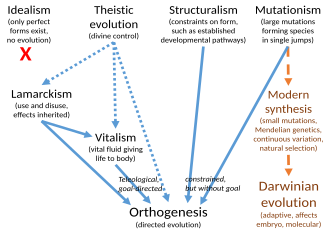

Multiple explanations have been offered

since the 19th century for how evolution took place, given that many

scientists initially had objections to natural selection. Many of these

theories led (solid blue arrows) to some form of orthogenesis, with or

without invoking divine control (dotted blue arrows) directly or indirectly. For example, evolutionists like Edward Drinker Cope believed in a combination of theistic evolution, Lamarckism, vitalism, and orthogenesis,

represented by a sequence of arrows on the left of the diagram. The

development of modern Darwinism is indicated by dashed orange arrows.

The various alternatives to Darwinian evolution by natural selection were not necessarily mutually exclusive. The evolutionary philosophy of the American paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope

is a case in point. Cope, a religious man, began his career denying the

possibility of evolution. In the 1860s, he accepted that evolution

could occur, but, influenced by Agassiz, rejected natural selection.

Cope accepted instead the theory of recapitulation of evolutionary

history during the growth of the embryo - that ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, which Agassiz believed showed a divine plan leading straight up to man, in a pattern revealed both in embryology and paleontology.

Cope did not go so far, seeing that evolution created a branching tree

of forms, as Darwin had suggested. Each evolutionary step was however

non-random: the direction was determined in advance and had a regular

pattern (orthogenesis), and steps were not adaptive but part of a divine

plan (theistic evolution). This left unanswered the question of why

each step should occur, and Cope switched his theory to accommodate

functional adaptation for each change. Still rejecting natural selection

as the cause of adaptation, Cope turned to Lamarckism to provide the

force guiding evolution. Finally, Cope supposed that Lamarckian use and

disuse operated by causing a vitalist growth-force substance,

"bathmism", to be concentrated in the areas of the body being most

intensively used; in turn, it made these areas develop at the expense of

the rest. Cope's complex set of beliefs thus assembled five

evolutionary philosophies: recapitulationism, orthogenesis, theistic

evolution, Lamarckism, and vitalism.

Other paleontologists and field naturalists continued to hold beliefs

combining orthogenesis and Lamarckism until the modern synthesis in the

1930s.

Status

In science

A satirical opinion of Ernst Haeckel's 1874 The modern theory of the descent of man, showing a linear sequence of forms leading up to 'Man'. Illustration by G. Avery for Scientific American, 11 March 1876

The stronger versions of the orthogenetic hypothesis began to lose

popularity when it became clear that they were inconsistent with the

patterns found by paleontologists in the fossil record,

which were non-rectilinear (richly branching) with many complications.

The hypothesis was abandoned by the mainstream of evolutionists when no

mechanism could be found that would account for the process, and the

theory of evolution by natural selection came to prevail. The historian of biology Edward J. Larson commented that

At theoretical and philosophical levels, Lamarckism and orthogenesis seemed to solve too many problems to be dismissed out of hand—yet biologists could never reliably document them happening in nature or in the laboratory. Support for both concepts evaporated rapidly once a plausible alternative appeared on the scene.

The modern synthesis of the 1930s and 1940s, in which the genetic

mechanisms of evolution were incorporated, appeared to refute the

hypothesis for good. As more was understood about these mechanisms it

came to be held that there was no naturalistic way in which the newly

discovered mechanism of heredity could be far-sighted or have a memory of past trends. Orthogenesis was seen to lie outside the methodological naturalism of the sciences.

Ernst Mayr considered orthogenesis effectively taboo in 1948.

By 1948, the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, as editor of the journal Evolution, made the use of the term orthogenesis

taboo: "It might be well to abstain from use of the word 'orthogenesis'

.. since so many of the geneticists seem to be of the opinion that the

use of the term implies some supernatural force." With the rise of evolutionary developmental biology

in the late 20th-early 21st centuries, however, which is open to an

expanded concept of heredity that incorporates the physics of self-organization, ideas of constraint and preferred directions of morphological change have made a reappearance in evolutionary theory.

For these and other reasons, belief in evolutionary progress has remained "a persistent heresy", among evolutionary biologists including E. O. Wilson and Simon Conway Morris, although often denied or veiled. The philosopher of biology Michael Ruse

wrote that "some of the most significant of today's evolutionists are

progressionists, and that because of this we find (absolute)

progressionism alive and well in their work." He argued that progressionism has harmed the status of evolutionary biology as a mature, professional science. Presentations of evolution remain characteristically progressionist, with humans at the top of the "Tower of Time" in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., while Scientific American

magazine could illustrate the history of life leading progressively

from mammals to dinosaurs to primates and finally man. Ruse noted that

at the popular level, progress and evolution are simply synonyms, as

they were in the nineteenth century, though confidence in the value of

cultural and technological progress has declined.

In popular culture

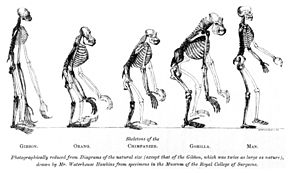

The frontispiece to Thomas Henry Huxley's 1863 Evidence as to Man's Place in Nature was intended to compare the skeletons of apes and humans, but unintentionally created a durable meme of supposed "monkey-to-man" progress.

In popular culture, progressionist images of evolution are widespread. The historian Jennifer Tucker, writing in The Boston Globe, notes that Thomas Henry Huxley's

1863 illustration comparing the skeletons of apes and humans "has

become an iconic and instantly recognizable visual shorthand for

evolution."

She calls its history extraordinary, saying that it is "one of the most

intriguing, and most misleading, drawings in the modern history of

science." Nobody, Tucker observes, supposes that the "monkey-to-man"

sequence accurately depicts Darwinian evolution. The Origin of Species

had only one illustration, a diagrams showing that random events create

a process of branching evolution, a view that Tucker notes is broadly

acceptable to modern biologists. But Huxley's image recalled the great

chain of being, implying with the force of a visual image a "logical,

evenly paced progression" leading up to Homo sapiens, a view denounced by Stephen Jay Gould in Wonderful Life.

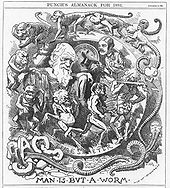

Man is But a Worm by Edward Linley Sambourne, Punch's Almanack for 1882

Popular perception, however, had seized upon the idea of linear progress. Edward Linley Sambourne's Man is But a Worm, drawn for Punch's Almanack,

mocked the idea of any evolutionary link between humans and animals,

with a sequence from chaos to earthworm to apes, primitive men, a

Victorian beau, and Darwin in a pose that according to Tucker recalls Michelangelo's figure of Adam in his fresco adorning the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. This was followed by a flood of variations on the evolution-as-progress theme, including The New Yorker's 1925 "The Rise and Fall of Man", the sequence running from a chimpanzee to Neanderthal man, Socrates, and finally the lawyer William Jennings Bryan who argued for the anti-evolutionist prosecution in the Scopes Trial on the State of Tennessee law limiting the teaching of evolution. Tucker noted that Rudolph Franz Zallinger's 1965 "The Road to Homo Sapiens" fold-out illustration in F. Clark Howell's Early Man,

showing a sequence of 14 walking figures ending with modern man, fitted

the paleoanthropological discoveries "not into a branching Darwinian

scheme, but into the framework of the original Huxley diagram." Howell

ruefully commented that the "powerful and emotional" graphic had

overwhelmed his Darwinian text.

One of many versions of the progressionist meme: Astronomy Evolution 2 artwork by Giuseppe Donatiello, 2016

Sliding between meanings

Scientists, Ruse argues, continue to slide easily from one notion of progress to another: even committed Darwinians like Richard Dawkins embed the idea of cultural progress in a theory of cultural units, memes, that act much like genes. Dawkins can speak of "progressive rather than random ... trends in evolution". Dawkins and John Krebs deny the "earlier [Darwinian] prejudice" that there is anything "inherently progressive about evolution", but the feeling of progress comes from evolutionary arms races

which remain in Dawkins's words "by far the most satisfactory

explanation for the existence of the advanced and complex machinery that

animals and plants possess".

Ruse concludes his detailed analysis of the idea of Progress,

meaning a progressionist philosophy, in evolutionary biology by stating

that evolutionary thought came out of that philosophy. Before Darwin,

Ruse argues, evolution was just a pseudoscience; Darwin made it respectable, but "only as popular science". "There it remained frozen, for nearly another hundred years", until mathematicians such as Fisher provided "both models and status", enabling evolutionary biologists to construct the modern synthesis

of the 1930s and 1940s. That made biology a professional science, at

the price of ejecting the notion of progress. That, Ruse argues, was a

significant cost to "people [biologists] still firmly committed to

Progress" as a philosophy.

Facilitated variation

Different species of Heliconius butterfly have independently evolved similar patterns, apparently both facilitated and constrained by the available developmental-genetic toolkit genes controlling wing pattern formation.

Biology has largely rejected the idea that evolution is guided in any way, but the evolution of some features is indeed facilitated by the genes of the developmental-genetic toolkit studied in evolutionary developmental biology. An example is the development of wing pattern in some species of Heliconius butterfly, which have independently evolved similar patterns. These butterflies are Müllerian mimics

of each other, so natural selection is the driving force, but their

wing patterns, which arose in separate evolutionary events, are

controlled by the same genes.