Social psychology is the scientific study of how people's thoughts, feelings and behaviors are influenced by the actual, imagined or implied presence of others. In this definition, scientific refers to the empirical investigation using the scientific method. The terms thoughts, feelings and behavior refer to psychological variables that can be measured in humans. The statement that others' presence may be imagined or implied

suggests that humans are malleable to social influences even when

alone, such as when watching television or following internalized cultural norms. Social psychologists typically explain human behavior as a result of the interaction of mental states and social situations.

Social psychologists examine factors that cause behaviors to

unfold in a given way in the presence of others. They study conditions

under which certain behavior, actions, and feelings occur. Social

psychology is concerned with the way these feelings, thoughts, beliefs,

intentions, and goals are cognitively constructed and how these mental

representations, in turn, influence our interactions with others.

Social psychology traditionally bridged the gap between psychology and sociology. During the years immediately following World War II there was frequent collaboration between psychologists and sociologists. The two disciplines, however, have become increasingly specialized and isolated from each other in recent years, with sociologists focusing on "macro variables" (e.g., social structure) to a much greater extent than psychologists.[citation needed] Nevertheless, sociological approaches to psychology remain an important counterpart to psychological research in this area.

In addition to the split between psychology and sociology, there has been a somewhat less pronounced difference in emphasis between American social psychologists and European social psychologists. As a generalization, American researchers traditionally have focused more on the individual, whereas Europeans have paid more attention to group level phenomena (see group dynamics).

Social psychology traditionally bridged the gap between psychology and sociology. During the years immediately following World War II there was frequent collaboration between psychologists and sociologists. The two disciplines, however, have become increasingly specialized and isolated from each other in recent years, with sociologists focusing on "macro variables" (e.g., social structure) to a much greater extent than psychologists.[citation needed] Nevertheless, sociological approaches to psychology remain an important counterpart to psychological research in this area.

In addition to the split between psychology and sociology, there has been a somewhat less pronounced difference in emphasis between American social psychologists and European social psychologists. As a generalization, American researchers traditionally have focused more on the individual, whereas Europeans have paid more attention to group level phenomena (see group dynamics).

History

Although there were some older writings about social psychology, such as those by Islamic philosopher Al-Farabi (Alpharabius),

the discipline of social psychology, as its modern-day definition,

began in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century. By that

time, though, the discipline had already developed a significant

foundation. Following the 18th century, those in the emerging field of

social psychology were concerned with developing concrete explanations

for different aspects of human nature.

They attempted to discover concrete cause and effect relationships that

explained the social interactions in the world around them. In order to

do so, they believed that the scientific method, an empirically based scientific measure, could be applied to human behavior.

The first published study in this area was an experiment in 1898 by Norman Triplett, on the phenomenon of social facilitation. During the 1930s, many Gestalt psychologists, most notably Kurt Lewin, fled to the United States from Nazi Germany. They were instrumental in developing the field as something separate from the behavioral and psychoanalytic schools that were dominant during that time, and social psychology has always maintained the legacy of their interests in perception and cognition. Attitudes and small group phenomena were the most commonly studied topics in this era.

During World War II, social psychologists studied persuasion and propaganda for the U.S. military. After the war, researchers became interested in a variety of social problems, including gender issues and racial prejudice. Most notable, revealing, and contentious of these were the Stanley Milgram shock experiments on obedience to authority. In the sixties, there was growing interest in new topics, such as cognitive dissonance, bystander intervention, and aggression.

By the 1970s, however, social psychology in America had reached a

crisis. There was heated debate over the ethics of laboratory

experimentation, whether or not attitudes really predicted behavior, and

how much science could be done in a cultural context. This was also the time when a radical situationist approach challenged the relevance of self and personality in psychology.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s social psychology reached a more mature

level. Two of the areas social psychology matured in were theories and

methods. Careful ethical standards now regulate research. Pluralistic and multicultural perspectives have emerged. Modern researchers are interested in many phenomena, but attribution, social cognition, and the self-concept are perhaps the greatest areas of growth in recent years.[citation needed]

Social psychologists have also maintained their applied interests with

contributions in the social psychology of health, education, law, and

the workplace.

Intrapersonal phenomena

Attitudes

In social psychology, attitudes are defined as learned, global

evaluations of a person, object, place, or issue that influence thought

and action.

Put more simply, attitudes are basic expressions of approval or

disapproval, favorability or unfavorability, or as Bem put it, likes and

dislikes. Examples would include liking chocolate ice cream, or endorsing the values of a particular political party.

Social psychologists have studied attitude formation, the

structure of attitudes, attitude change, the function of attitudes, and

the relationship between attitudes and behavior. Because people are

influenced by the situation, general attitudes are not always good

predictors of specific behavior. For example, for a variety of reasons, a

person may value the environment but not recycle a can on a particular

day.

In recent times, research on attitudes has examined the

distinction between traditional, self-reported attitude measures and

"implicit" or unconscious attitudes. For example, experiments using the Implicit Association Test

have found that people often demonstrate implicit bias against other

races, even when their explicit responses reveal equal mindedness. One

study found that explicit attitudes correlate with verbal behavior in

interracial interactions, whereas implicit attitudes correlate with

nonverbal behavior.

One hypothesis on how attitudes are formed, first advanced by Abraham Tesser in 1983, is that strong likes and dislikes are ingrained in our genetic make-up. Tesser speculates that individuals are disposed to hold certain strong attitudes as a result of inborn physical, sensory, and cognitive skills, temperament, and personality traits.

Whatever disposition nature elects to give us, our most treasured

attitudes are often formed as a result of exposure to attitude objects;

our history of rewards and punishments; the attitude that our parents,

friends, and enemies express; the social and cultural context in which

we live; and other types of experiences we have. Obviously, attitudes

are formed through the basic process of learning. Numerous studies have

shown that people can form strong positive and negative attitudes toward

neutral objects that are in some way linked to emotionally charged

stimuli.

Attitudes are also involved in several other areas of the discipline, such as conformity, interpersonal attraction, social perception, and prejudice.

Persuasion

The topic of persuasion has received a great deal of attention in

recent years. Persuasion is an active method of influence that attempts

to guide people toward the adoption of an attitude, idea, or behavior by

rational or emotive means. Persuasion relies on "appeals" rather than

strong pressure or coercion.

Numerous variables have been found to influence the persuasion process;

these are normally presented in five major categories: who said what to whom and how.

- The Communicator, including credibility, expertise, trustworthiness, and attractiveness.

- The Message, including varying degrees of reason, emotion (such as fear), one-sided or two sided arguments, and other types of informational content.

- The Audience, including a variety of demographics, personality traits, and preferences.

- The Channel or Medium, including the printed word, radio, television, the internet, or face-to-face interactions.

- The Context, including the environment, group dynamics, and preamble to the message.

Dual-process theories of persuasion

maintain that the persuasive process is mediated by two separate

routes; central and peripheral. The central route of persuasion is more

fact-based and results in longer lasting change, but requires motivation

to process. The peripheral route is more superficial and results in

shorter lasting change, but does not require as much motivation to

process. An example of a peripheral route of persuasion might be a

politician using a flag lapel pin, smiling, and wearing a crisp, clean

shirt. Notice that this does not require motivation to be persuasive,

but should not last as long as persuasion based on the central route. If

that politician were to outline exactly what they believed, and their

previous voting record, this would be using the central route, and would

result in longer lasting change, but would require a good deal of

motivation to process.

Social cognition

Social cognition is a growing area of social psychology that studies

how people perceive, think about, and remember information about others. Much research rests on the assertion that people think about (other) people differently from non-social targets. This assertion is supported by the social cognitive deficits exhibited by people with Williams syndrome and autism. Person perception

is the study of how people form impressions of others. The study of how

people form beliefs about each other while interacting is known as interpersonal perception.

A major research topic in social cognition is attribution.

Attributions are the explanations we make for people's behavior, either

our own behavior or the behavior of others. One element of attribution

ascribes the locus of a behavior to either internal or external factors.

An internal, or dispositional, attribution assigns behavior to

causes related to inner traits such as personality, disposition,

character or ability. An external, or situational, attribution involves situational elements, such as the weather.

A second element of attribution ascribes the cause of behavior to

either stable or unstable factors (whether the behavior will be repeated

or changed under similar circumstances). Finally, we also attribute

causes of behavior to either controllable or uncontrollable factors: how

much control one has over the situation at hand.

Numerous biases in the attribution process have been discovered. For instance, the fundamental attribution error

is the tendency to make dispositional attributions for behavior,

overestimating the influence of personality and underestimating the

influence of situations.

The actor-observer difference is a refinement of this bias, the

tendency to make dispositional attributions for other people's behavior

and situational attributions for our own. The self-serving bias

is the tendency to attribute dispositional causes for successes, and

situational causes for failure, particularly when self-esteem is

threatened. This leads to assuming one's successes are from innate

traits, and one's failures are due to situations, including other

people. Other ways people protect their self-esteem are by believing in a just world, blaming victims for their suffering, and making defensive attributions, which explain our behavior in ways which defend us from feelings of vulnerability and mortality. Researchers have found that mildly depressed individuals often lack this bias and actually have more realistic perceptions of reality (as measured by the opinions of others).

Heuristics

are cognitive short cuts. Instead of weighing all the evidence when

making a decision, people rely on heuristics to save time and energy.

The availability heuristic occurs when people estimate the probability

of an outcome based on how easy that outcome is to imagine. As such,

vivid or highly memorable possibilities will be perceived as more likely

than those that are harder to picture or are difficult to understand,

resulting in a corresponding cognitive bias.

The representativeness heuristic is a shortcut people use to categorize

something based on how similar it is to a prototype they know of. Numerous other biases have been found by social cognition researchers. The hindsight bias is a false memory of having predicted events, or an exaggeration of actual predictions, after becoming aware of the outcome. The confirmation bias is a type of bias leading to the tendency to search for, or interpret information in a way that confirms one's preconceptions.

Another key concept in social cognition is the assumption that

reality is too complex to easily discern. As a result, we tend to see

the world according to simplified schemas or images of reality. Schemas are generalized mental representations that organize knowledge and guide information processing. Schemas often operate automatically

and unintentionally, and can lead to biases in perception and memory.

Expectations from schemas may lead us to see something that is not

there. One experiment found that people are more likely to misperceive a

weapon in the hands of a black man than a white man. This type of schema is actually a stereotype, a generalized set of beliefs about a particular group of people (when incorrect, an ultimate attribution error). Stereotypes are often related to negative or preferential attitudes (prejudice) and behavior (discrimination). Schemas for behaviors (e.g., going to a restaurant, doing laundry) are known as scripts.

Self-concept

Self-concept is a term referring to the whole sum of beliefs that

people have about themselves. However, what specifically does

self-concept consist of? According to Hazel Markus (1977), the

self-concept is made up of cognitive molecules called self-schemas –

beliefs that people have about themselves that guide the processing of

self-reliant information. For example, an athlete at a university would

have multiple selves that would process different information pertinent

to each self: the student would be one "self," who would process

information pertinent to a student (taking notes in class, completing a

homework assignment, etc.); the athlete would be the "self" who

processes information about things related to being an athlete

(recognizing an incoming pass, aiming a shot, etc.). These "selves" are

part of one's identity and the self-reliant information is the

information that relies on the proper "self" to process and react on it.

If a "self" is not part of one's identity, then it is much more

difficult for one to react. For example, a civilian may not know how to

handle a hostile threat as a trained Marine would. The Marine contains a

"self" that would enable him/her to process the information about the

hostile threat and react accordingly, whereas a civilian may not contain

that self, disabling them from properly processing the information from

the hostile threat and, furthermore, debilitating them from acting

accordingly. Self-schemas are to an individual’s total self–concept as a

hypothesis is to a theory, or a book is to a library. A good example is

the body weight self-schema; people who regard themselves as over or

underweight, or for those whom body image is a significant self-concept

aspect, are considered schematics with respect to weight. For

these people a range of otherwise mundane events – grocery shopping, new

clothes, eating out, or going to the beach – can trigger thoughts about

the self. In contrast, people who do not regard their weight as an

important part of their lives are a-schematic on that attribute.

It is rather clear that the self is a special object of our attention. Whether one is mentally focused on a memory, a conversation, a foul smell, the song that is stuck in one's head, or this sentence, consciousness is like a spotlight. This spotlight

can shine on only one object at a time, but it can switch rapidly from

one object to another and process the information out of awareness. In this spotlight the self is front and center: things relating to the self have the spotlight more often.

The self's ABCs are affect, behavior, and cognition. An affective

(or emotional) question: How do people evaluate themselves, enhance

their self-image, and maintain a secure sense of identity? A behavioral

question: How do people regulate their own actions and present

themselves to others according to interpersonal demands? A cognitive question: How do individuals become themselves, build a self-concept, and uphold a stable sense of identity?

Affective forecasting is the process of predicting how one would feel in response to future emotional events. Studies done by Timothy Wilson and Daniel Gilbert

in 2003 have shown that people overestimate the strength of reaction to

anticipated positive and negative life events that they actually feel

when the event does occur.

There are many theories on the perception of our own behavior.

Daryl Bem's (1972) self-perception theory claims that when internal cues

are difficult to interpret, people gain self-insight by observing their

own behavior. Leon Festinger's 1954 social comparison theory

is that people evaluate their own abilities and opinions by comparing

themselves to others when they are uncertain of their own ability or

opinions. There is also the facial feedback hypothesis: that changes in facial expression can lead to corresponding changes in emotion.

The fields of social psychology and personality

have merged over the years, and social psychologists have developed an

interest in self-related phenomena. In contrast with traditional

personality theory, however, social psychologists place a greater

emphasis on cognitions than on traits. Much research focuses on the self-concept, which is a person's understanding of their self. The self-concept is often divided into a cognitive component, known as the self-schema, and an evaluative component, the self-esteem. The need to maintain a healthy self-esteem is recognized as a central human motivation in the field of social psychology.

Self-efficacy

beliefs are associated with the self-schema. These are expectations

that performance on some task will be effective and successful. Social

psychologists also study such self-related processes as self-control and self-presentation.

People develop their self-concepts by varied means, including introspection, feedback from others, self-perception,

and social comparison. By comparing themselves to relevant others,

people gain information about themselves, and they make inferences that

are relevant to self-esteem. Social comparisons can be either "upward"

or "downward," that is, comparisons to people who are either higher in

status or ability, or lower in status or ability. Downward comparisons are often made in order to elevate self-esteem.

Self-perception is a specialized form of attribution that

involves making inferences about oneself after observing one's own

behavior. Psychologists have found that too many extrinsic rewards (e.g.

money) tend to reduce intrinsic motivation through the self-perception

process, a phenomenon known as overjustification. People's attention is directed to the reward and they lose interest in the task when the reward is no longer offered. This is an important exception to reinforcement theory.

Interpersonal phenomena

Social influence

Social influence is an overarching term given to describe the

persuasive effects people have on each other. It is seen as a

fundamental value in social psychology and overlaps considerably with

research on attitudes and persuasion. The three main areas of social

influence include: conformity, compliance, and obedience.

Social influence is also closely related to the study of group

dynamics, as most principles of influence are strongest when they take

place in social groups.

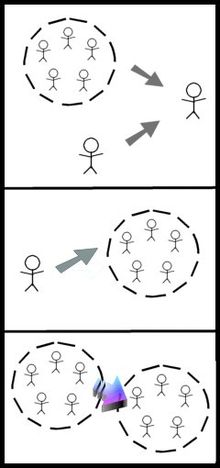

The first major area of social influence is conformity.

Conformity is defined as the tendency to act or think like other members

of a group. The identity of members within a group, i.e. status,

similarity, expertise, as well as cohesion, prior commitment, and

accountability to the group help to determine the level of conformity of

an individual. Individual variation among group members plays a key

role in the dynamic of how willing people will be to conform.

Conformity is usually viewed as a negative tendency in American

culture, but a certain amount of conformity is adaptive in some

situations, as is nonconformity in other situations.

Which line matches the first line, A, B, or C? In the Asch conformity experiments, people frequently followed the majority judgment, even when the majority was (objectively) wrong.

The second major area of social influence research is compliance. Compliance refers to any change in behavior that is due to a request or suggestion from another person. The foot-in-the-door technique

is a compliance method in which the persuader requests a small favor

and then follows up with requesting a larger favor, e.g., asking for the

time and then asking for ten dollars. A related trick is the bait and switch.

The third major form of social influence is obedience;

this is a change in behavior that is the result of a direct order or

command from another person. Obedience as a form of compliance was

dramatically highlighted by the Milgram study, wherein people were ready to administer shocks to a person in distress on a researcher's command.

An unusual kind of social influence is the self-fulfilling prophecy. This is a prediction that, in being made, actually causes itself to become true. For example, in the stock market, if it is widely believed that a crash

is imminent, investors may lose confidence, sell most of their stock,

and thus actually cause the crash. Similarly, people may expect

hostility in others and actually induce this hostility by their own

behavior.

Group dynamics

A group can be defined as two or more individuals that are connected to each another by social relationships.

Groups tend to interact, influence each other, and share a common

identity. They have a number of emergent qualities that distinguish them

from aggregates:

- Norms: Implicit rules and expectations for group members to follow, e.g. saying thank you, shaking hands.

- Roles: Implicit rules and expectations for specific members within the group, e.g. the oldest sibling, who may have additional responsibilities in the family.

- Relations: Patterns of liking within the group, and also differences in prestige or status, e.g., leaders, popular people.

Temporary groups and aggregates share few or none of these features,

and do not qualify as true social groups. People waiting in line to get

on a bus, for example, do not constitute a group.

Groups are important not only because they offer social support,

resources, and a feeling of belonging, but because they supplement an

individual's self-concept. To a large extent, humans define themselves

by the group memberships which form their social identity. The shared social identity of individuals within a group influences inter-group behavior,

the way in which groups behave towards and perceive each other. These

perceptions and behaviors in turn define the social identity of

individuals within the interacting groups. The tendency to define

oneself by membership in a group may lead to intergroup discrimination,

which involves favorable perceptions and behaviors directed towards the

in-group, but negative perceptions and behaviors directed towards the

out-group.

On the other hand, such discrimination and segregation may sometimes

exist partly to facilitate a diversity which strengthens society. Inter-group discrimination leads to prejudice and stereotyping, while the processes of social facilitation and group polarization encourage extreme behaviors towards the out-group.

Groups often moderate and improve decision making,

and are frequently relied upon for these benefits, such as in

committees and juries. A number of group biases, however, can interfere

with effective decision making. For example, group polarization,

formerly known as the "risky shift," occurs when people polarize their

views in a more extreme direction after group discussion. More

problematic is the phenomenon of group-think.

This is a collective thinking defect that is characterized by a

premature consensus or an incorrect assumption of consensus, caused by

members of a group failing to promote views which are not consistent

with the views of other members. Group-think occurs in a variety of

situations, including isolation of a group and the presence of a highly

directive leader. Janis offered the 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion as a historical case of group-think.

Groups also affect performance and productivity.

Social facilitation, for example, is a tendency to work harder and

faster in the presence of others. Social facilitation increases the dominant response's likelihood, which tends to improve performance on simple tasks and reduce it on complex tasks. In contrast, social loafing is the tendency of individuals to slack off

when working in a group. Social loafing is common when the task is

considered unimportant and individual contributions are not easy to see.

Social psychologists study group-related (collective) phenomena such as the behavior of crowds. An important concept in this area is deindividuation, a reduced state of self-awareness

that can be caused by feelings of anonymity. Deindividuation is

associated with uninhibited and sometimes dangerous behavior. It is

common in crowds and mobs, but it can also be caused by a disguise, a

uniform, alcohol, dark environments, or online anonymity.

Social psychologists study interactions within groups, and between both groups and individuals.

Interpersonal attraction

A major area in the study of people's relations to each other is

interpersonal attraction. This refers to all forces that lead people to

like each other, establish relationships, and (in some cases) fall in love.

Several general principles of attraction have been discovered by social

psychologists, but many still continue to experiment and do research to

find out more. One of the most important factors in interpersonal

attraction is how similar two particular people are. The more similar

two people are in general attitudes, backgrounds, environments,

worldviews, and other traits, the more probable an attraction is

possible.

Physical attractiveness is an important element of romantic relationships, particularly in the early stages characterized by high levels of passion.

Later on, similarity and other compatibility factors become more

important, and the type of love people experience shifts from passionate to companionate. Robert Sternberg has suggested that there are actually three components of love: intimacy, passion, and commitment. When two (or more) people experience all three, they are said to be in a state of consummate love.

According to social exchange theory,

relationships are based on rational choice and cost-benefit analysis.

If one partner's costs begin to outweigh their benefits, that person may

leave the relationship, especially if there are good alternatives

available. This theory is similar to the minimax principle proposed by mathematicians and economists (despite the fact that human relationships are not zero-sum games). With time, long term relationships tend to become communal rather than simply based on exchange.

Research

Methods

Social psychology is an empirical

science that attempts to answer questions about human behavior by

testing hypotheses, both in the laboratory and in the field. Careful

attention to sampling, research design, and statistical analysis is important; results are published in peer reviewed journals such as the Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Social psychology studies also appear in general science journals such as Psychological Science and Science.

Experimental methods

involve the researcher altering a variable in the environment and

measuring the effect on another variable. An example would be allowing

two groups of children to play violent or nonviolent video games, and

then observing their subsequent level of aggression during free-play

period. A valid experiment is controlled and uses random assignment.

Correlational methods

examine the statistical association between two naturally occurring

variables. For example, one could correlate the amount of violent

television children watch at home with the number of violent incidents

the children participate in at school. Note that this study would not

prove that violent TV causes aggression in children: it is quite

possible that aggressive children choose to watch more violent TV.

Observational methods are purely descriptive and include naturalistic observation,

"contrived" observation, participant observation, and archival

analysis. These are less common in social psychology but are sometimes

used when first investigating a phenomenon. An example would be to

unobtrusively observe children on a playground (with a videocamera,

perhaps) and record the number and types of aggressive actions

displayed.

Whenever possible, social psychologists rely on controlled

experimentation. Controlled experiments require the manipulation of one

or more independent variables in order to examine the effect on a dependent variable. Experiments are useful in social psychology because they are high in internal validity, meaning that they are free from the influence of confounding

or extraneous variables, and so are more likely to accurately indicate a

causal relationship. However, the small samples used in controlled

experiments are typically low in external validity,

or the degree to which the results can be generalized to the larger

population. There is usually a trade-off between experimental control (internal validity) and being able to generalize to the population (external validity).

Because it is usually impossible to test everyone, research tends to be conducted on a sample of persons from the wider population. Social psychologists frequently use survey research when they are interested in results that are high in external validity. Surveys use various forms of random sampling

to obtain a sample of respondents that are representative of a

population. This type of research is usually descriptive or

correlational because there is no experimental control over variables.

However, new statistical methods like structural equation modeling are being used to test for potential causal relationships in this type of data. Some psychologists, including Dr. David O. Sears,

have criticized social psychological research for relying too heavily

on studies conducted on university undergraduates in academic settings.

Over 70% of experiments in Sears' study used North American

undergraduates as subjects, a subset of the population that may not be

representative of the population as a whole.

Regardless of which method has been chosen to be used, the

results are of high importance. Results need to be used to evaluate the

hypothesis of the research that is done. These results should either

confirm or reject the original hypothesis that was predicted.There are

two different types of testing social psychologists use in order to test

their results. Statistics and probability testing define a significant finding that can be as low as 5% or less, likely to be due to chance. Replications are important, to ensure that the result is valid and not due to chance, or some feature of a particular sample. False positive conclusions, often resulting from the pressure to publish or the author's own confirmation bias, are a hazard in the field.

Ethics

The goal

of social psychology is to understand cognition and behavior as they

naturally occur in a social context, but the very act of observing

people can influence and alter their behavior. For this reason, many

social psychology experiments utilize deception

to conceal or distort certain aspects of the study. Deception may

include false cover stories, false participants (known as confederates

or stooges), false feedback given to the participants, and so on.

The practice of deception has been challenged by some

psychologists who maintain that deception under any circumstances is

unethical, and that other research strategies (e.g., role-playing)

should be used instead. Unfortunately, research has shown that

role-playing studies do not produce the same results as deception

studies and this has cast doubt on their validity.

In addition to deception, experimenters have at times put people into

potentially uncomfortable or embarrassing situations (e.g., the Milgram experiment), and this has also been criticized for ethical reasons.

To protect the rights and well-being of research participants,

and at the same time discover meaningful results and insights into human

behavior, virtually all social psychology research must pass an ethical review process. At most colleges and universities, this is conducted by an ethics committee or Institutional Review Board.

This group examines the proposed research to make sure that no harm is

likely to be done to the participants, and that the study's benefits

outweigh any possible risks or discomforts to people taking part in the

study.

Furthermore, a process of informed consent is often used to make sure that volunteers know what will happen in the experiment and understand that they are allowed to quit the experiment at any time. A debriefing

is typically done at the experiment's conclusion in order to reveal any

deceptions used and generally make sure that the participants are

unharmed by the procedures.

Today, most research in social psychology involves no more risk of harm

than can be expected from routine psychological testing or normal daily

activities.

Replication crisis

Social psychology has recently found itself at the center of a "replication crisis"

due to some research findings proving difficult to replicate.

Replication failures are not unique to social psychology and are found

in all fields of science. However, several factors have combined to put

social psychology at the center of the current controversy.

Firstly, questionable research practices

(QRP) have been identified as common in the field. Such practices,

while not necessarily intentionally fraudulent, involve converting

undesired statistical outcomes into desired outcomes via the

manipulation of statistical analyses, sample size or data management,

typically to convert non-significant findings into significant ones. Some studies have suggested that at least mild versions of QRP are highly prevalent. One of the critics of Daryl Bem in the feeling the future controversy has suggested that the evidence for precognition in this study could (at least in part) be attributed to QRP.

Secondly, social psychology has found itself at the center of

several recent scandals involving outright fraudulent research. Most

notably the admitted data fabrication by Diederik Stapel

as well as allegations against others. However, most scholars

acknowledge that fraud is, perhaps, the lesser contribution to

replication crises.

Third, several effects in social psychology have been found to be

difficult to replicate even before the current replication crisis. For

example, the scientific journal Judgment and Decision Making has published several studies over the years that fail to provide support for the unconscious thought theory.

Replications appear particularly difficult when research trials are

pre-registered and conducted by research groups not highly invested in

the theory under questioning.

These three elements together have resulted in renewed attention for replication supported by Daniel Kahneman.

Scrutiny of many effects have shown that several core beliefs are hard

to replicate. A recent special edition of the journal Social Psychology

focused on replication studies and a number of previously held beliefs

were found to be difficult to replicate. A 2012 special edition of the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science also focused on issues ranging from publication bias to null-aversion that contribute to the replication crises in psychology.

It is important to note that this replication crisis does not mean that social psychology is unscientific.

Rather this process is a healthy if sometimes acrimonious part of the

scientific process in which old ideas or those that cannot withstand

careful scrutiny are pruned.

The consequence is that some areas of social psychology once

considered solid, such as social priming, have come under increased

scrutiny due to failed replications.

Famous experiments

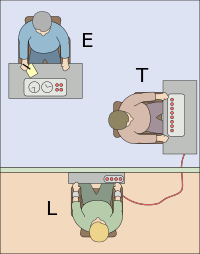

The Milgram experiment:

The experimenter (E) persuades the participant (T) to give what the

participant believes are painful electric shocks to another participant

(L), who is actually an actor. Many participants continued to give

shocks despite pleas for mercy from the actor.

The Asch conformity experiments demonstrated the power of conformity in small groups with a line length estimation task that was designed to be extremely easy.

In well over a third of the trials, participants conformed to the

majority, who had been instructed to provide incorrect answers, even

though the majority judgment was clearly wrong. Seventy-five percent of

the participants conformed at least once during the experiment.

Additional manipulations to the experiment showed participant conformity

decreased when at least one other individual failed to conform, but

increased when the individual began conforming or withdrew from the

experiment.

Also, participant conformity increased substantially as the number of

incorrect individuals increased from one to three, and remained high as

the incorrect majority grew. Participants with three incorrect

opponents made mistakes 31.8% of the time, while those with one or two

incorrect opponents made mistakes only 3.6% and 13.6% of the time,

respectively.

Muzafer Sherif's Robbers' Cave Experiment

divided boys into two competing groups to explore how much hostility

and aggression would emerge. Sherif's explanation of the results became

known as realistic group conflict theory, because the intergroup

conflict was induced through competition over resources. Inducing cooperation and superordinate goals later reversed this effect.

In Leon Festinger's

cognitive dissonance experiment, participants were asked to perform a

boring task. They were divided into 2 groups and given two different pay

scales. At the study's end, some participants were paid $1 to say that

they enjoyed the task and another group of participants was paid $20 to

say the same lie. The first group ($1) later reported liking the task

better than the second group ($20). Festinger's explanation was that for

people in the first group being paid only $1 is not sufficient

incentive for lying and those who were paid $1 experienced dissonance.

They could only overcome that dissonance by justifying their lies by

changing their previously unfavorable attitudes about the task. Being

paid $20 provides a reason for doing the boring task, therefore no

dissonance.

One of the most notable experiments in social psychology was the Milgram experiment, which studied how far people would go to obey an authority figure. Following the events of The Holocaust

in World War II, the experiment showed that (most) normal American

citizens were capable of following orders from an authority even when

they believed they were causing an innocent person to suffer.

Albert Bandura's Bobo doll experiment demonstrated how aggression is learned by imitation. This set of studies fueled debates regarding media violence which continue to be waged among scholars.