From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The "open source hardware" logo proposed by OSHWA, one of the main defining organizations

The RepRap general-purpose 3D printer with the ability to make copies of most of its own structural parts

Open-source hardware (OSH) consists of physical artifacts of technology designed and offered by the open-design movement. Both free and open-source software (FOSS) and open-source hardware are created by this open-source culture movement and apply a like concept to a variety of components. It is sometimes, thus, referred to as FOSH

(free and open-source hardware). The term usually means that

information about the hardware is easily discerned so that others can

make it – coupling it closely to the maker movement. Hardware design (i.e. mechanical drawings, schematics, bills of material, PCB layout data, HDL source code and integrated circuit layout data), in addition to the software that drives the hardware, are all released under free/libre

terms. The original sharer gains feedback and potentially improvements

on the design from the FOSH community. There is now significant evidence

that such sharing can drive a high return on investment for the scientific community.

Since the rise of reconfigurable programmable logic devices, sharing of logic designs has been a form of open-source hardware. Instead of the schematics, hardware description language (HDL) code is shared. HDL descriptions are commonly used to set up system-on-a-chip systems either in field-programmable gate arrays (FPGA) or directly in application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) designs. HDL modules, when distributed, are called semiconductor intellectual property cores, also known as IP cores.

History

openhardware.org logo (2013)

OSHWA logo

The first hardware focused "open source" activities were started around 1997 by Bruce Perens, creator of the Open Source Definition, co-founder of the Open Source Initiative, and a ham radio operator.

He launched the Open Hardware Certification Program, which had the goal

of allowing hardware manufacturers to self-certify their products as

open.

Shortly after the launch of the Open Hardware Certification

Program, David Freeman announced the Open Hardware Specification Project

(OHSpec), another attempt at licensing hardware components whose

interfaces are available publicly and of creating an entirely new

computing platform as an alternative to proprietary computing systems.

In early 1999, Sepehr Kiani, Ryan Vallance and Samir Nayfeh joined

efforts to apply the open-source philosophy to machine design

applications. Together they established the Open Design Foundation (ODF)

as a non-profit corporation and set out to develop an Open Design Definition. But most of these activities faded out after a few years.

By the mid 2000s open-source hardware again became a hub of

activity due to the emergence of several major open-source hardware

projects and companies, such as OpenCores, RepRap (3D printing), Arduino, Adafruit and SparkFun. In 2007, Perens reactivated the openhardware.org website.

Following the Open Graphics Project,

an effort to design, implement, and manufacture a free and open 3D

graphics chip set and reference graphics card, Timothy Miller suggested

the creation of an organization to safeguard the interests of the Open

Graphics Project community. Thus, Patrick McNamara founded the Open Hardware Foundation (OHF) in 2007.

The Tucson Amateur Packet Radio Corporation

(TAPR), founded in 1982 as a non-profit organization of amateur radio

operators with the goals of supporting R&D efforts in the area of

amateur digital communications, created in 2007 the first open hardware

license, the TAPR Open Hardware License. The OSI president Eric S. Raymond expressed some concerns about certain aspects of the OHL and decided to not review the license.

Around 2010 in context of the Freedom Defined project, the Open Hardware Definition was created as collaborative work of many and is accepted as of 2016 by dozens of organizations and companies.

In July 2011, CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) released an open-source hardware license, CERN OHL.

Javier Serrano, an engineer at CERN's Beams Department and the founder

of the Open Hardware Repository, explained: "By sharing designs openly,

CERN expects to improve the quality of designs through peer review and

to guarantee their users – including commercial companies – the freedom

to study, modify and manufacture them, leading to better hardware and

less duplication of efforts".

While initially drafted to address CERN-specific concerns, such as

tracing the impact of the organization’s research, in its current form

it can be used by anyone developing open-source hardware.

Following the 2011 Open Hardware Summit, and after heated debates

on licenses and what constitutes open-source hardware, Bruce Perens

abandoned the OSHW Definition and the concerted efforts of those

involved with it.

Openhardware.org, led by Bruce Perens, promotes and identifies

practices that meet all the combined requirements of the Open Source

Hardware Definition, the Open Source Definition, and the Four Freedoms

of the Free Software Foundation Since 2014 openhardware.org is not online and seems to have ceased activity.

The Open Source Hardware Association (OSHWA) at oshwa.org proposes Open source hardware

and acts as hub of open source hardware activity of all genres, while

cooperating with other entities such as TAPR, CERN, and OSI. The OSHWA

was established as an organization in June 2012 in Delaware and filed

for tax exemption status in July 2013. After same debates about trademark interferences with the OSI, in 2012 the OSHWA and the OSI signed a co-existence agreement.

FSF's Replicant project suggested in 2016 an alternative "free hardware" definition, derived from the FSF's four freedoms.

Forms of open-source hardware

The term hardware in open source hardware has been historically used in opposition to the term software

of open source software. That is, to refer to the electronic hardware

on which the software runs (see previous section). However, as more and

more non-electronic hardware products are made open source (for example

Wikihouse, OpenBeam or Hovalin), this term tends to be used back in its

broader sense of "physical product". The field of open source hardware

has been shown to go beyond electronic hardware and to cover a larger

range of product categories such as machine tools, vehicles and medical

equipment. In that sense, hardware

refers to any form of tangible product, may it be electronic hardware,

mechanical hardware, textile or even construction hardware. The Open

Source Hardware (OSHW) Definition 1.0 defines hardware as "tangible

artifacts — machines, devices, or other physical things".

Computers

Due

to a mixture of privacy, security, and environmental concerns, a number

of projects have started that aim to deliver a variety of open-source

computing devices. Examples include the EOMA68 (SBC in a PCMCIA form-factor, intended to be plugged into a laptop or desktop chassis), Novena (bare motherboard with optional laptop chassis), and GnuBee (series of Network Attached Storage devices).

Several retrocomputing hobby groups have created numerous recreations or adaptations of the early home computers of the 1970s and 80s, some of which include improved functionality and more modern components (such as surface-mount ICs and SD card readers). Some hobbyists have also developed add-on cards (such as drive controllers, memory expansion, and sound cards) to improve the functionality of older computers. Miniaturised recreations of vintage computers have also been created.

Electronics

One

of the most popular types of open-source hardware is electronics. There

are numerous companies that provide large varieties of open-source

electronics such as Sparkfun, Adafruit and Seeed. In addition, there are NPOs and companies that provide a specific open-source electronic component such as the Arduino

electronics prototyping platform. There are numerous examples of

speciality open-source electronics such as low-cost voltage and current

GMAW open-source 3-D printer monitor and a robotics-assisted mass spectrometry assay platform. Open-source electronics finds various uses, including automation of chemical procedures.

Mecha(tro)nics

A

large range of products including mechanical components have been

developed so far, from machine tools to vehicles over musical

instruments and medical equipment. Examples of machine-tools are the 3D printers RepRap and Ultimaker as well as the laser cutter Lasersaur. In the category vehicles, we can find bikes like XYZ Space Frame Vehicles and cars like the Tabby OSVehicle. Examples of medical equipment are the echostethoscope echOpen and a wide range of prosthetic hands listed in the review study by Ten Kate et.al. e.g. the OpenBionics’ Prosthetic Hands.

Others

Examples of open-source hardware products can also be found to a lesser extent in construction (Wikihouse) and textile (Kit Zéro Kilomètres).

Licenses

Rather than creating a new license, some open-source hardware projects simply use existing, free and open-source software licenses. These licenses may not accord well with patent law.

Later, several new licenses have been proposed, designed to address issues specific to hardware designs.

In these licenses, many of the fundamental principles expressed in

open-source software (OSS) licenses have been "ported" to their

counterpart hardware projects. New hardware licenses are often explained as the "hardware equivalent" of a well-known OSS license, such as the GPL, LGPL, or BSD license.

Despite superficial similarities to software licenses, most hardware licenses are fundamentally different: by nature, they typically rely more heavily on patent law than on copyright law, as many hardware designs are not copyrightable.

Whereas a copyright license may control the distribution of the source

code or design documents, a patent license may control the use and

manufacturing of the physical device built from the design documents.

This distinction is explicitly mentioned in the preamble of the TAPR Open Hardware License:

"... those who benefit from an OHL design may not bring lawsuits claiming that design infringes their patents or other intellectual property."

— TAPR Open Hardware License

Noteworthy licenses include:

- The TAPR Open Hardware License: drafted by attorney John Ackermann, reviewed by OSS community leaders Bruce Perens and Eric S. Raymond, and discussed by hundreds of volunteers in an open community discussion

- Balloon Open Hardware License: used by all projects in the Balloon Project

- Although originally a software license, OpenCores encourages the LGPL

- Hardware Design Public License: written by Graham Seaman, admin. of Opencollector.org

- In March 2011 CERN released the CERN Open Hardware License (OHL) intended for use with the Open Hardware Repository and other projects.

- The Solderpad License is a version of the Apache License version 2.0, amended by lawyer Andrew Katz to render it more appropriate for hardware use.

The Open Source Hardware Association recommends seven licenses which follow their open-source hardware definition. From the general copyleft licenses the GNU General Public License (GPL) and Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike license, from the HW specific copyleft licenses the CERN Open Hardware License (OHL) and TAPR Open Hardware License (OHL) and from the permissive licenses the FreeBSD license, the MIT license, and the Creative Commons Attribution license. Openhardware.org recommended in 2012 the TAPR Open Hardware License, Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 and GPL 3.0 license.

Organizations tend to rally around a shared license. For example, OpenCores prefers the LGPL or a Modified BSD License, FreeCores insists on the GPL, Open Hardware Foundation promotes "copyleft or other permissive licenses", the Open Graphics Project uses a variety of licenses, including the MIT license, GPL, and a proprietary license, and the Balloon Project wrote their own license.

Development

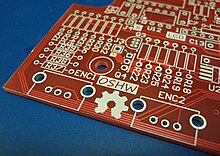

The OSHW (Open Source Hardware) logo silkscreened on an unpopulated PCB

The

adjective "open-source" not only refers to a specific set of freedoms

applying to a product, but also generally presupposes that the product

is the object or the result of a "process that relies on the

contributions of geographically dispersed developers via the Internet."

In practice however, in both fields of open-source hardware and

open-source software, products may either be the result of a development

process performed by a closed team in a private setting or by a

community in a public environment, the first case being more frequent

than the second which is more challenging.

Establishing a community-based product development process faces

several challenges such as: to find appropriate product data management

tools, document not only the product but also the development process

itself, accepting losing ubiquitous control over the project, ensure

continuity in a context of fickle participation of voluntary project

members, among others.

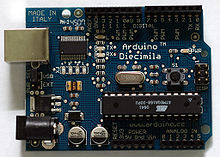

The Arduino Diecimila, another popular and early open source hardware design.

One of the major differences between developing open-source software

and developing open-source hardware is that hardware results in tangible

outputs, which cost money to prototype and manufacture. As a result,

the phrase "free as in speech, not as in beer", more formally known as Gratis versus Libre,

distinguishes between the idea of zero cost and the freedom to use and

modify information. While open-source hardware faces challenges in

minimizing cost and reducing financial risks for individual project

developers, some community members have proposed models to address these

needs

Given this, there are initiatives to develop sustainable community

funding mechanisms, such as the Open Source Hardware Central Bank.

Extensive discussion has taken place on ways to make open-source hardware as accessible as open-source software.

Providing clear and detailed product documentation is an essential

factor facilitating product replication and collaboration in hardware

development projects. Practical guides have been developed to help

practitioners to do so. Another option is to design products so they are easy to replicate, as exemplified in the concept of open-source appropriate technology.

The process of developing open-source hardware in a community-based setting is alternatively called open design, open source development or open source product development. All these terms are instantiations of the open-source model applicable for the development of any product, may it be software, hardware, cultural, educational, and so on.

A major contributor to the production of open-source hardware

product designs is the scientific community. There has been considerable

work to produce open-source hardware for scientific hardware using a

combination of open-source electronics and 3-D printing.

Other sources of open-source hardware production are vendors of chips

and other electronic components sponsoring contests with the provision

that the participants and winners must share their designs. Circuit Cellar magazine organizes some of these contests.

Open-source labs

A guide has been published (Open-Source Lab (book) by Joshua Pearce) on using open-source electronics and 3D printing to make open-source labs. Today scientists are creating many such labs, examples include:

Cover for "Open-Source Lab" by Joshua M. Pearce (2014)

- Boston Open Source Science Laboratory, Somerville, Massachusetts

- BYU Open Source Lab, Brigham Young University

- Michigan Tech

- National Tsing Hua University

- OSU Open Source Lab, Oregon State University

- Open Source Research Lab, University of Texas at El Paso

Business models

Open hardware companies are experimenting with different business models. In one example, littleBits

implements open-source business models by making the design files

available for the circuit designs in each littleBits module, in

accordance with the CERN Open Hardware License Version 1.2. In another example, Arduino has registered its name as a trademark.

Others may manufacture their designs but can't put the Arduino name on

them. Thus they can distinguish their products from others by

appellation.

There are many applicable business models for implementing some

open-source hardware even in traditional firms. For example, to

accelerate development and technical innovation the photovoltaic industry has experimented with partnerships, franchises, secondary supplier and completely open-source models.

Recently, many open source hardware projects were funded via crowdfunding on Indiegogo or Kickstarter. Especially popular is Crowd Supply for crowdfunding open hardware projects.

Reception and impact

Richard Stallman, the founder of the free software movement, was in 1999 skeptical on the idea and relevance of Free hardware (his terminology for what is now known as open-source hardware). In a 2015 Wired

article he adapted his point of view slightly; while he still sees no

ethical parallel between free software and free hardware, he

acknowledges the importance. Also, Stallman uses and suggests the term free hardware design over open source hardware, a request which is consistent with his earlier rejection of the term open source software.

Other authors, such as Joshua Pearce have argued there is an ethical imperative for open-source hardware – specifically with respect to open-source appropriate technology for sustainable development. In 2014, he also wrote the book Open-Source Lab: How to Build Your Own Hardware and Reduce Research Costs, which details the development of free and open-source hardware primarily for scientists and university faculty. A new scientific journal has also been introduced by Prof. Pearce in partnership with Elsevier: HardwareX. It has featured numerous examples of applications of open source hardware for scientific purposes.

Find open-source hardware products

Some ongoing initiatives provide indexes of open-source hardware products for different purposes:

An autosampler for liquid or gaseous samples based on a microsyringe

- The Open Source Hardware Association provides a certification programme and maintains a directory of certified products.

- The Observatory of Open Source Hardware aims at supporting exchange of best practices between practitioners. It maintains an open access and curated directory of open source hardware products rated according to their degree of openness. This directory contains references of more than 200 complex open source hardware products.

- The P2P Foundation maintains an Open Hardware Directory as well.