Welfare capitalism is capitalism that includes social welfare policies.

Welfare capitalism is also the practice of businesses providing welfare

services to their employees. Welfare capitalism in this second sense,

or industrial paternalism, was centered on industries that employed skilled labor and peaked in the mid-20th century.

Today, welfare capitalism is most often associated with the models of capitalism found in Central Mainland and Northern Europe, such as the Nordic model, social market economy and Rhine capitalism. In some cases welfare capitalism exists within a mixed economy, but welfare states can and do exist independently of policies common to mixed economies such as state interventionism and extensive regulation.

Language

"Welfare

capitalism" or "welfare corporatism" is somewhat neutral language for

what, in other contexts, might be framed as "industrial paternalism",

"industrial village", "company town", "representative plan", "industrial betterment", or "company union".

History

In the

19th century, some companies—mostly manufacturers—began offering new

benefits for their employees. This began in Britain in the early 19th

century and also occurred in other European countries, including France

and Germany. These companies sponsored sports teams, established social clubs,

and provided educational and cultural activities for workers. Some

offered housing as well. Welfare corporatism in the United States

developed during the intense industrial development of 1880 to 1900 which was marked by labor disputes and strikes, many violent.

Cooperatives and model villages

Robert Owen

was a utopian socialist of the early 19th century, who introduced one

of the first private systems of philanthropic welfare for his workers at

the cotton mills of New Lanark. He embarked on a scheme in New Harmony, Indiana to create a model cooperative, called the New Moral World, (pictured). Owenites fired bricks to build it, but construction never took place.

One of the first attempts at offering philanthropic welfare to workers was made at the New Lanark mills in Scotland by the social reformer Robert Owen. He became manager and part owner of the mills in 1810, and encouraged by his success in the management of cotton mills in Manchester (see also Quarry Bank Mill),

he hoped to conduct New Lanark on higher principles and focus less on

commercial profit. The general condition of the people was very

unsatisfactory. Many of the workers were steeped in theft and

drunkenness, and other vices were common; education and sanitation were

neglected and most families lived in one room. The respectable country

people refused to submit to the long hours and demoralising drudgery of

the mills. Many employers also operated the truck system,

whereby payment to the workers was made in part or totally by tokens.

These tokens had no value outside the mill owner's "truck shop". The

owners were able to supply shoddy goods to the truck shop and charge top

prices. A series of "Truck Acts" (1831–1887) eventually stopped this abuse, by making it an offence not to pay employees in common currency.

Owen opened a store where the people could buy goods of sound

quality at little more than wholesale cost, and he placed the sale of

alcohol under strict supervision. He sold quality goods and passed on

the savings from the bulk purchase of goods to the workers. These

principles became the basis for the cooperative stores

in Britain that continue to trade today. Owen's schemes involved

considerable expense, which displeased his partners. Tired of the

restrictions on his actions, Owen bought them out in 1813. New Lanark

soon became celebrated throughout Europe, with many leading royals,

statesmen and reformers visiting the mills. They were astonished to find

a clean, healthy industrial environment with a content, vibrant

workforce and a prosperous, viable business venture all rolled into one.

Owen’s philosophy was contrary to contemporary thinking, but he was

able to demonstrate that it was not necessary for an industrial

enterprise to treat its workers badly to be profitable. Owen was able to

show visitors the village’s excellent housing and amenities, and the

accounts showing the profitability of the mills.

Owen and the French socialist Henri de Saint-Simon were the fathers of the utopian socialist

movement; they believed that the ills of industrial work relations

could be removed by the establishment of small cooperative communities.

Boarding houses were built near the factories for the workers'

accommodation. These so-called model villages

were envisioned as a self-contained community for the factory workers.

Although the villages were located close to industrial sites, they were

generally physically separated from them and generally consisted of

relatively high quality housing, with integrated community amenities and

attractive physical environments.

The first such villages were built in the late 18th century, and

they proliferated in England in the early 19th century with the

establishment of Trowse, Norfolk in 1805 and Blaise Hamlet, Bristol in 1811. In America, boarding houses were built for textile workers in Lowell, Massachusetts in the 1820s.

The motive behind these offerings was paternalistic—owners were

providing for workers in ways they felt was good for them. These

programs did not address the problems of long work hours, unsafe

conditions, and employment insecurity that plagued industrial workers

during that period, however. Indeed, employers who provided housing in

company towns (communities established by employers where stores and

housing were run by companies) often faced resentment from workers who

chafed at the control owners had over their housing and commercial

opportunities. A noted example was Pullman, Illinois—a

site of a strike that destroyed the town in 1894. During these years,

disputes between employers and workers often turned violent and led to

government intervention.

Welfare as a business model

The Cadbury factory at Bournville, c.1903, where workers worked in conditions that were very good for the time

In the early years of the 20th century, however, business leaders began embracing a different approach. The Cadbury family of philanthropists and business entrepreneurs set up the model village at Bournville,

England in 1879 for their chocolate making factory. Loyal and

hard-working workers were treated with great respect and relatively high

wages and good working conditions; Cadbury pioneered pension schemes, joint works committees and a full staff medical service. By 1900, the estate included 313 'Arts and Crafts' cottages and houses; traditional in design but with large gardens and modern interiors, they were designed by the resident architect William Alexander Harvey.

The Cadburys were also concerned with the health and fitness of

their workforce, incorporating park and recreation areas into the

Bournville village plans and encouraging swimming, walking and indeed all forms of outdoor sports. In the early 1920s, extensive football and hockey

pitches were opened together with a grassed running track. Rowheath

Pavilion served as the clubhouse and changing rooms for the acres of

sports playing fields, several bowling greens, a fishing lake and an

outdoor swimming lido, a natural mineral spring forming the source for

the lido's

healthy waters. The whole area was specifically for the benefit of the

Cadbury workers and their families with no charges for the use of any of

the sporting facilities by Cadbury employees or their families.

An example of the workers' housing at Port Sunlight, built by the Lever Brothers in 1888

Port Sunlight in Wirral, England was built by the Lever Brothers

to accommodate workers in its soap factory in 1888. By 1914, the model

village could house a population of 3,500. The garden village had

allotments and public buildings including the Lady Lever Art Gallery, a cottage hospital, schools, a concert hall, open air swimming pool, church, and a temperance

hotel. Lever introduced welfare schemes, and provided for the education

and entertainment of his workforce, encouraging recreation and

organisations which promoted art, literature, science or music.

Lever's aims were "to socialise and Christianise business

relations and get back to that close family brotherhood that existed in

the good old days of hand labour." He claimed that Port Sunlight was an

exercise in profit sharing,

but rather than share profits directly, he invested them in the

village. He said, "It would not do you much good if you send it down

your throats in the form of bottles of whisky, bags of sweets, or fat

geese at Christmas. On the other hand, if you leave the money with me, I

shall use it to provide for you everything that makes life

pleasant—nice houses, comfortable homes, and healthy recreation."

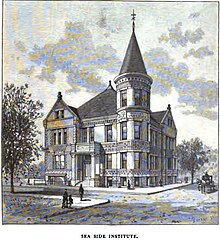

The Seaside Institute, designed by Warren R. Briggs in 1887 for the benefit of the female employees of the Warner Brothers Corset Company

In America in the early 20th century, businessmen like George F. Johnson and Henry B. Endicott

began to seek new relations with their labor by offering the workers

wage incentives and other benefits. The point was to increase

productivity by creating good will with employees. When Henry Ford

introduced his $5-a-day pay rate in 1914 (when most workers made $11 a

week), his goal was to reduce turnover and build a long-term loyal labor

force that would have higher productivity.

Turnover in manufacturing plants in the U.S. from 1910 to 1919 averaged

100%. Wage incentives and internal promotion opportunities were

intended to encourage good attendance and loyalty.

This would reduce turnover and improve productivity. The combination of

high pay, high efficiency and cheap consumer goods was known as Fordism, and was widely discussed throughout the world.

Led by the railroads and the largest industrial corporations such as the Pullman Car Company, Standard Oil, International Harvester, Ford Motor Company and United States Steel,

businesses provided numerous services to its employees, including paid

vacations, medical benefits, pensions, recreational facilities, sex

education and the like. The railroads, in order to provide places for

itinerant trainmen to rest, strongly supported YMCA hotels, and built railroad YMCAs. The Pullman Car Company build an entire model town, Pullman, Illinois. The Seaside Institute is an example of a social club built for the particular benefit of women workers. Most of these programs proliferated after World War I—in the 1920s.

The economic upheaval of the Great Depression in the 1930s

brought many of these programs to a halt. Employers cut cultural

activities and stopped building recreational facilities as they

struggled to stay solvent. It wasn't until after World War II that many

of these programs reappeared—and expanded to include more blue-collar

workers. Since this time, programs like on-site child care and

substance abuse treatment have waxed and waned in use/popularity, but

other welfare capitalism components remain. Indeed, in the U.S., the

health care system is largely built around employer-sponsored plans.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Germany and Britain

created "safety nets" for their citizens, including public welfare and unemployment insurance. These government operated welfare systems is the sense in which the term 'welfare capitalism' is generally understood today.

Modern welfare capitalism

The 19th century German economist, Gustav von Schmoller,

defined welfare capitalism as government provision for the welfare of

workers and the public via social legislation. Western Europe,

Scandinavia, Canada and Australasia are regions noted for their welfare state provisions, though other countries have publicly financed universal healthcare and other elements of the welfare state as well.

A sample Medicare card

Esping-Andersen categorized three different traditions of welfare provision in his 1990 book 'The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism'; Social Democracy, Christian Democracy (conservatism) and Liberalism.

Though increasingly criticized, these classifications remain the most

commonly used in distinguishing types of modern welfare states, and

offer a solid starting point in such analysis. It has been argued that

these typologies remain a fundamental heuristic tool for welfare state

scholars, even for those who claim that in-depth analysis of a single

case is more suited to capture the complexity of different social policy

arrangements. Welfare typologies have the function to provide a

comparative lens and place even the single case into a comparative

perspective (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011).

The ideal Social-Democratic welfare state

is based on the principle of universalism granting access to benefits

and services based on citizenship. Such a welfare state is said to

provide a relatively high degree of autonomy, limiting the reliance of

family and market (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011). In this context, social policies are perceived as 'politics against the market' (Esping-Andersen 1985). Christian-democratic welfare states

are based on the principle of subsidiarity and the dominance of social

insurance schemes, offering a medium level of decommodification and a

high degree of social stratification. The liberal regime

is based on the notion of market dominance and private provision;

ideally, the state only interferes to ameliorate poverty and provide for

basic needs, largely on a means-tested basis. Hence, the

decommodification potential of state benefits is assumed to be low and

social stratification high (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011).

Based on the decommodification index Esping-Andersen divided into

the following regimes 18 OECD countries (Esping-Andersen 1990: 71):

- Liberal: Australia, Canada, Japan, Switzerland and the US;

- Christian democratic: Austria, Belgium, France, Germany and Italy;

- Social democratic: Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden

- Not clearly classified: Ireland, New Zealand and the United Kingdom.

These 18 countries can be placed on a continuum from the most purely

social-democratic, Sweden, to the most liberal country, the United

States (Ferragina and Seeleib-Kaiser 2011).

In Europe

The Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg

European welfare capitalism is typically endorsed by Christian democrats and social democrats. In contrast to social welfare provisions found in other industrialized countries (especially countries with the Anglo-Saxon model

of capitalism), European welfare states provide universal services that

benefit all citizens (social democratic welfare state) as opposed to a

minimalist model that only caters to the needs of the poor.

In Northern European countries, welfare capitalism is often combined with social corporatism and national-level collective bargaining arrangements aimed at balancing the power between labor and business. The most prominent example of this system is the Nordic model,

which features free and open markets with limited regulation, high

concentrations of private ownership in industry, and tax-funded

universal welfare benefits for all citizens.

An alternative model of welfare exists in Continental European countries, known as the social market economy or German model,

which includes a greater role for government interventionism into the

macro-economy but features a less generous welfare state than is found

in the Nordic countries.

In France, the welfare state exists alongside a dirigiste mixed economy.

In the United States

Welfare capitalism in the United States refers to industrial relations policies of large, usually non-unionized, companies that have developed internal welfare systems for their employees. Welfare capitalism first developed in the United States in the 1880s and gained prominence in the 1920s.

Promoted by business leaders during a period marked by widespread

economic insecurity, social reform activism, and labor unrest, it was

based on the idea that Americans should look not to the government or to

labor unions but to the workplace benefits provided by private-sector

employers for protection against the fluctuations of the market economy.

Companies employed these types of welfare policies to encourage worker

loyalty, productivity and dedication. Owners feared government

intrusion in the Progressive Era,

and labor uprisings from 1917 to 1919—including strikes against

"benevolent" employers—showed the limits of paternalistic efforts.

For owners, the corporation was the most responsible social

institution and it was better suited, in their minds, to promoting the

welfare of employees than government. Welfare capitalism was their way of heading off radicalism and regulation then.

The benefits offered by welfare capitalist employers were often

inconsistent and varied widely from firm to firm. They included minimal

benefits such as cafeteria plans,

company-sponsored sports teams, lunchrooms and water fountains in

plants, and company newsletters/magazines—as well as more extensive

plans providing retirement benefits, health care, and employee

profit-sharing. Examples of companies that have practiced welfare capitalism include Kodak, Sears, and IBM,

with the main elements of the employment system in these companies

including permanent employment, internal labor markets, extensive

security and fringe benefits, and sophisticated communications and

employee involvement.

Anti-unionism

Welfare

capitalism was also used as a way to resist government regulation of

markets, independent labor union organizing, and the emergence of a

welfare state. Welfare capitalists went to great lengths to quash

independent trade union organizing, strikes,

and other expressions of labor collectivism—through a combination of

violent suppression, worker sanctions, and benefits in exchange for

loyalty.

Also, employee stock-ownership programs meant to tie workers to the

success of companies (and accordingly to management). Workers would

then be actual partners with owners—and capitalists themselves. Owners

intended these programs to ward off the threat of "Bolshevism" and

undermine the appeal of unions.

The least popular of the welfare capitalism programs were the

company unions created to stave off labor activism. By offering

employees a say in company policies and practices and a means for

appealing disputes internally, employers hoped to reduce the lure of

unions. They dubbed these employee representation plans "industrial

democracy."

Efficacy

In the end, welfare capitalism programs benefited white-collar workers far more than those on the factory floor in the early 20th century. The average annual bonus payouts at U.S. Steel Corporation from 1929 to 1931 were approximately $2,500,000; however, in 1929, $1,623,753 of that went to the president of the company.

Real wages for unskilled and low-skilled workers grew little in the

1920s, while long hours in unsafe conditions continued to be the norm.

Further, employment instability due to layoffs

remained a reality of work life. Welfare capitalism programs rarely

worked as intended, company unions only reinforced that authority of

management over the terms of employment.

Wage incentives (merit raises and bonuses) often led to a speed-up in production for factory lines.

As much as these programs meant to encourage loyalty to the company,

this effort was often undermined by continued layoffs and frustrations

with working conditions. Employees

soured on employee representation plans and cultural activities, but

they were eager for opportunities to improve their pay with good work

and attendance and to gain benefits like medical care. These programs

gave workers new expectations for their employers. They were often

disappointed in the execution of them but supported their aims. The post-World War II

era saw an expansion of these programs for all workers, and today,

these benefits remain part of employment relations in many countries.

Recently, however, there has been a trend away from this form of welfare

capitalism, as corporations have reduced the portion of compensation

paid with health care, and shifted from defined benefit pensions to

employee-funded defined contribution plans.