Brown dwarfs are substellar objects that occupy the mass range between the heaviest gas giant planets and the lightest stars, having masses between approximately 13 to 75–80 times that of Jupiter (MJ), or approximately 2.5×1028 kg to about 1.5×1029 kg. Below this range are the sub-brown dwarfs (sometimes referred to as rogue planets), and above it are the lightest red dwarfs (M9 V). Brown dwarfs may be fully convective, with no layers or chemical differentiation by depth.

Unlike the stars in the main sequence, brown dwarfs are not massive enough to sustain nuclear fusion of ordinary hydrogen (1H) to helium in their cores. They are, however, thought to fuse deuterium (2H) and to fuse lithium (7Li) if their mass is above a debated threshold of 13 MJ and 65 MJ, respectively. It is also debated whether brown dwarfs would be better defined by their formation processes rather than by their supposed nuclear fusion reactions.

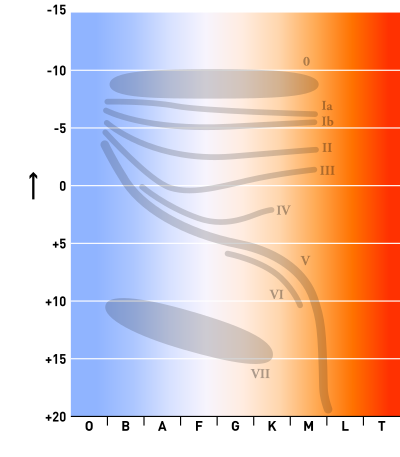

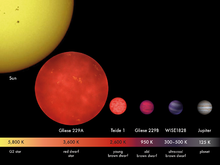

Stars are categorized by spectral class, with brown dwarfs designated as types M, L, T, and Y. Despite their name, brown dwarfs are of different colors. Many brown dwarfs would likely appear magenta to the human eye, or possibly orange/red. Brown dwarfs are not very luminous at visible wavelengths.

There are planets known to orbit brown dwarfs: 2M1207b, MOA-2007-BLG-192Lb, and 2MASS J044144b.

At a distance of about 6.5 light years, the nearest known brown dwarf is Luhman 16, a binary system of brown dwarfs discovered in 2013. HR 2562 b is listed as the most-massive known exoplanet (as of December 2017) in NASA's exoplanet archive, despite having a mass (30±15 MJ) more than twice the 13-Jupiter-mass cutoff between planets and brown dwarfs.

History

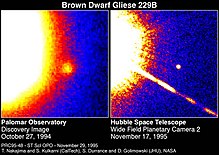

The smaller object is Gliese 229B, about 20 to 50 times the mass of Jupiter, orbiting the star Gliese 229. It is in the constellation Lepus, about 19 light years from Earth.

Early theorizing

The objects now called "brown dwarfs" were theorized to exist in the 1960s by Shiv S. Kumar and were originally called black dwarfs,

a classification for dark substellar objects floating freely in space

that were not massive enough to sustain hydrogen fusion. However:

(a) the term black dwarf was already in use to refer to a cold white dwarf; (b) red dwarfs

fuse hydrogen; and (c) these objects may be luminous at visible

wavelengths early in their lives. Because of this, alternative names for

these objects were proposed, including planetar and substar. In 1975, Jill Tarter suggested the term "brown dwarf", using "brown" as an approximate color.

The term "black dwarf" still refers to a white dwarf

that has cooled to the point that it no longer emits significant

amounts of light. However, the time required for even the lowest-mass

white dwarf to cool to this temperature is calculated to be longer than the current age of the universe; hence such objects are expected to not yet exist.

Early theories concerning the nature of the lowest-mass stars and the hydrogen-burning limit suggested that a population I object with a mass less than 0.07 solar masses (M☉) or a population II object less than 0.09 M☉ would never go through normal stellar evolution and would become a completely degenerate star.

The first self-consistent calculation of the hydrogen-burning minimum

mass confirmed a value between 0.08 and 0.07 solar masses for population

I objects.

Deuterium fusion

The discovery of deuterium burning down to 0.012 solar masses and the impact of dust formation in the cool outer atmospheres

of brown dwarfs in the late 1980s brought these theories into question.

However, such objects were hard to find because they emit almost no

visible light. Their strongest emissions are in the infrared (IR) spectrum, and ground-based IR detectors were too imprecise at that time to readily identify any brown dwarfs.

Since then, numerous searches by various methods have sought

these objects. These methods included multi-color imaging surveys around

field stars, imaging surveys for faint companions of main-sequence dwarfs and white dwarfs, surveys of young star clusters, and radial velocity monitoring for close companions.

GD 165B and class "L"

For many years, efforts to discover brown dwarfs were fruitless. In 1988, however, a faint companion to a star known as GD 165

was found in an infrared search of white dwarfs. The spectrum of the

companion GD 165B was very red and enigmatic, showing none of the

features expected of a low-mass red dwarf. It became clear that GD 165B would need to be classified as a much cooler object than the latest M dwarfs then known. GD 165B remained unique for almost a decade until the advent of the Two Micron All-Sky Survey (2MASS) which discovered many objects with similar colors and spectral features.

Today, GD 165B is recognized as the prototype of a class of objects now called "L dwarfs".

Although the discovery of the coolest dwarf was highly

significant at the time, it was debated whether GD 165B would be

classified as a brown dwarf or simply a very-low-mass star, because

observationally it is very difficult to distinguish between the two.

Soon after the discovery of GD 165B, other brown-dwarf candidates

were reported. Most failed to live up to their candidacy, however,

because the absence of lithium showed them to be stellar objects. True

stars burn their lithium within a little over 100 Myr,

whereas brown dwarfs (which can, confusingly, have temperatures and

luminosities similar to true stars) will not. Hence, the detection of

lithium in the atmosphere of an object older than 100 Myr ensures that

it is a brown dwarf.

Gliese 229B and class "T" – the methane dwarfs

In 1995, the study of brown dwarfs changed substantially with the discovery of two indisputable substellar objects – Teide 1 and Gliese 229B

– which were identified by the presence of the 670.8 nm lithium line.

The latter was found to have a temperature and luminosity well below the

stellar range.

Its near-infrared spectrum clearly exhibited a methane absorption

band at 2 micrometers, a feature that had previously only been observed

in the atmospheres of giant planets and that of Saturn's moon Titan.

Methane absorption is not expected at any temperature of a

main-sequence star. This discovery helped to establish yet another

spectral class even cooler than L dwarfs, known as "T dwarfs", for which Gliese 229B is the prototype.

Teide 1 – the first class "M" brown dwarf

The first confirmed brown dwarf was discovered by Spanish astrophysicists Rafael Rebolo (head of team), María Rosa Zapatero Osorio, and Eduardo Martín in 1994. This object, found in the Pleiades open cluster, received the name Teide 1. The discovery article was submitted to Nature in May 1995, and published on 14 September 1995. Nature highlighted "Brown dwarfs discovered, official" in the front page of that issue.

Teide 1 was discovered in images collected by the IAC team on 6 January 1994 using the 80 cm telescope (IAC 80) at Teide Observatory and its spectrum was first recorded in December 1994 using the 4.2 m William Herschel Telescope at Roque de los Muchachos Observatory

(La Palma). The distance, chemical composition, and age of Teide 1

could be established because of its membership in the young Pleiades

star cluster. Using the most advanced stellar and substellar evolution

models at that moment, the team estimated for Teide 1 a mass of 55 ± 15 MJ, which is below the stellar-mass limit. The object became a reference in subsequent young brown dwarf related works.

In theory, a brown dwarf below 65 MJ

is unable to burn lithium by thermonuclear fusion at any time during

its evolution. This fact is one of the lithium test principles used to

judge the substellar nature of low-luminosity and

low-surface-temperature astronomical bodies.

High-quality spectral data acquired by the Keck 1 telescope in

November 1995 showed that Teide 1 still had the initial lithium

abundance of the original molecular cloud from which Pleiades stars

formed, proving the lack of thermonuclear fusion in its core. These

observations confirmed that Teide 1 is a brown dwarf, as well as the

efficiency of the spectroscopic lithium test.

For some time, Teide 1 was the smallest known object outside the

Solar System that had been identified by direct observation. Since then,

over 1,800 brown dwarfs have been identified, even some very close to Earth like Epsilon Indi Ba and Bb, a pair of brown dwarfs gravitationally bound to a Sun-like star 12 light-years from the Sun, and Luhman 16, a binary system of brown dwarfs at 6.5 light-years from the Sun.

Theory

The standard mechanism for star birth is through the gravitational collapse of a cold interstellar cloud of gas and dust. As the cloud contracts it heats due to the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism.

Early in the process the contracting gas quickly radiates away much of

the energy, allowing the collapse to continue. Eventually, the central

region becomes sufficiently dense to trap radiation. Consequently, the

central temperature and density of the collapsed cloud increases

dramatically with time, slowing the contraction, until the conditions

are hot and dense enough for thermonuclear reactions to occur in the

core of the protostar. For most stars, gas and radiation pressure generated by the thermonuclear fusion reactions within the core of the star will support it against any further gravitational contraction. Hydrostatic equilibrium is reached and the star will spend most of its lifetime fusing hydrogen into helium as a main-sequence star.

If, however, the mass of the protostar is less than about 0.08 M☉, normal hydrogen thermonuclear fusion reactions will not ignite in the core. Gravitational contraction does not heat the small protostar

very effectively, and before the temperature in the core can increase

enough to trigger fusion, the density reaches the point where electrons

become closely packed enough to create quantum electron degeneracy pressure.

According to the brown dwarf interior models, typical conditions in the

core for density, temperature and pressure are expected to be the

following:

This means that the protostar is not massive enough and not dense

enough to ever reach the conditions needed to sustain hydrogen fusion.

The infalling matter is prevented, by electron degeneracy pressure, from

reaching the densities and pressures needed.

Further gravitational contraction is prevented and the result is a

"failed star", or brown dwarf that simply cools off by radiating away

its internal thermal energy.

High-mass brown dwarfs versus low-mass stars

Lithium

is generally present in brown dwarfs and not in low-mass stars. Stars,

which reach the high temperature necessary for fusing hydrogen, rapidly

deplete their lithium. Fusion of lithium-7 and a proton occurs producing two helium-4

nuclei. The temperature necessary for this reaction is just below that

necessary for hydrogen fusion. Convection in low-mass stars ensures that

lithium in the whole volume of the star is eventually depleted.

Therefore, the presence of the lithium spectral line in a candidate

brown dwarf is a strong indicator that it is indeed a substellar object.

The lithium test

The use of lithium to distinguish candidate brown dwarfs from low-mass stars is commonly referred to as the lithium test, and was pioneered by Rafael Rebolo, Eduardo Martín and Antonio Magazzu. However, lithium is also seen in very young stars, which have not yet had enough time to burn it all.

Heavier stars, like the Sun, can also retain lithium in their

outer layers, which never get hot enough to fuse lithium, and whose

convective layer does not mix with the core where the lithium would be

rapidly depleted. Those larger stars are easily distinguishable from

brown dwarfs by their size and luminosity.

Conversely, brown dwarfs at the high end of their mass range can

be hot enough to deplete their lithium when they are young. Dwarfs of

mass greater than 65 MJ can burn their lithium by the time they are half a billion years old, thus the lithium test is not perfect.

Atmospheric methane

Unlike

stars, older brown dwarfs are sometimes cool enough that, over very

long periods of time, their atmospheres can gather observable quantities

of methane which cannot form in hotter objects. Dwarfs confirmed in this fashion include Gliese 229B.

Iron rain

Main-sequence stars cool, but eventually reach a minimum bolometric luminosity that they can sustain through steady fusion. This varies from star to star, but is generally at least 0.01% that of the Sun. Brown dwarfs cool and darken steadily over their lifetimes: sufficiently old brown dwarfs will be too faint to be detectable.

Iron rain

as part of atmospheric convection processes is possible only in brown

dwarfs, and not in small stars. The spectroscopy research into iron rain

is still ongoing, but not all brown dwarfs will always have this

atmospheric anomaly. In 2013, a heterogeneous iron-containing atmosphere

was imaged around the B component in the close Luhman 16 system.

Low-mass brown dwarfs versus high-mass planets

An artistic concept of the brown dwarf around the star HD 29587, a companion known as HD 29587 b, and estimated to be about 55 Jupiter masses.

Like stars, brown dwarfs form independently, but, unlike stars, lack

sufficient mass to "ignite". Like all stars, they can occur singly or in

close proximity to other stars. Some orbit stars and can, like planets,

have eccentric orbits.

Size and fuel-burning ambiguities

Brown dwarfs are all roughly the same radius as Jupiter. At the high end of their mass range (60–90 MJ), the volume of a brown dwarf is governed primarily by electron-degeneracy pressure, as it is in white dwarfs; at the low end of the range (10 MJ), their volume is governed primarily by Coulomb pressure,

as it is in planets. The net result is that the radii of brown dwarfs

vary by only 10–15% over the range of possible masses. This can make

distinguishing them from planets difficult.

In addition, many brown dwarfs undergo no fusion; those at the low end of the mass range (under 13 MJ) are never hot enough to fuse even deuterium, and even those at the high end of the mass range (over 60 MJ) cool quickly enough that after 10 million years they no longer undergo fusion.

Heat spectrum

X-ray and infrared spectra are telltale signs of brown dwarfs. Some emit X-rays; and all "warm" dwarfs continue to glow tellingly in the red and infrared spectra until they cool to planet-like temperatures (under 1000 K).

Gas giants have some of the characteristics of brown dwarfs. Like the Sun, Jupiter and Saturn

are both made primarily of hydrogen and helium. Saturn is nearly as

large as Jupiter, despite having only 30% the mass. Three of the giant

planets in the Solar System (Jupiter, Saturn, and Neptune) emit much more (up to about twice) heat than they receive from the Sun. And all four giant planets have their own "planetary" systems – their moons.

Current IAU standard

Currently, the International Astronomical Union considers an object above 13 MJ

(the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium) to be a brown

dwarf, whereas an object under that mass (and orbiting a star or

stellar remnant) is considered a planet.

The 13 Jupiter-mass cutoff is a rule of thumb rather than

something of precise physical significance. Larger objects will burn

most of their deuterium and smaller ones will burn only a little, and

the 13 Jupiter mass value is somewhere in between. The amount of deuterium burnt also depends to some extent on the composition of the object, specifically on the amount of helium and deuterium present and on the fraction of heavier elements, which determines the atmospheric opacity and thus the radiative cooling rate.

The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia includes objects up to 25 Jupiter masses, and the Exoplanet Data Explorer up to 24 Jupiter masses.

Sub-brown dwarf

Objects below 13 MJ, called sub-brown dwarf or planetary-mass brown dwarf, form in the same manner as stars and brown dwarfs (i.e. through the collapse of a gas cloud) but have a mass below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium.

Some researchers call them free-floating planets, whereas others call them planetary-mass brown dwarfs.

Observations

Classification of brown dwarfs

Spectral class M

Artist's vision of a late-M dwarf

These are brown dwarfs with a spectral class of M6.5 or later; they are also called late-M dwarfs.

Spectral class L

Artist's vision of an L-dwarf

The defining characteristic of spectral class M, the coolest type in the long-standing classical stellar sequence, is an optical spectrum dominated by absorption bands of titanium(II) oxide (TiO) and vanadium(II) oxide (VO) molecules. However, GD 165B, the cool companion to the white dwarf GD 165,

had none of the hallmark TiO features of M dwarfs. The subsequent

identification of many objects like GD 165B ultimately led to the

definition of a new spectral class, the L dwarfs, defined in the red optical region of the spectrum not by metal-oxide absorption bands (TiO, VO), but by metal hydride emission bands (FeH, CrH, MgH, CaH) and prominent atomic lines of alkali metals (NaI, KI, CsI, RbI). As of 2013, over 900 L dwarfs have been identified, most by wide-field surveys: the Two Micron All Sky Survey (2MASS), the Deep Near Infrared Survey of the Southern Sky (DENIS), and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS). This spectral class contains not only the brown dwarfs, because the coolest main-sequence stars above brown dwarfs (> 80 MJ) have the spectral

class L2 or L3.

Spectral class T

Artist's vision of a T-dwarf

As GD 165B is the prototype of the L dwarfs, Gliese 229B is the prototype of a second new spectral class, the T dwarfs. Whereas near-infrared (NIR) spectra of L dwarfs show strong absorption bands of H2O and carbon monoxide (CO), the NIR spectrum of Gliese 229B is dominated by absorption bands from methane (CH4), features that were only found in the giant planets of the Solar System and Titan. CH4, H2O, and molecular hydrogen (H2)

collision-induced absorption (CIA) give Gliese 229B blue near-infrared

colors. Its steeply sloped red optical spectrum also lacks the FeH and

CrH bands that characterize L dwarfs and instead is influenced by

exceptionally broad absorption features from the alkali metals Na and K. These differences led Kirkpatrick to propose the T spectral class for objects exhibiting H- and K-band CH4 absorption. As of 2013, 355 T dwarfs are known.

NIR classification schemes for T dwarfs have recently been developed by

Adam Burgasser and Tom Geballe. Theory suggests that L dwarfs are a

mixture of very-low-mass stars and sub-stellar objects (brown dwarfs),

whereas the T dwarf class is composed entirely of brown dwarfs. Because

of the absorption of sodium and potassium in the green part of the spectrum of T dwarfs, the actual appearance of T dwarfs to human visual perception is estimated to be not brown, but the color of magenta. T-class brown dwarfs, such as WISE 0316+4307, have been detected over 100 light-years from the Sun.

Spectral class Y

Artist's vision of a Y-dwarf

There is some doubt as to what, if anything, should be included in the class Y dwarfs. They are expected to be much cooler than T-dwarfs. They have been modeled, though there is no well-defined spectral sequence yet with prototypes.

In 2009, the coolest known brown dwarfs had estimated effective temperatures between 500 and 600 K, and have been assigned the spectral class T9. Three examples are the brown dwarfs CFBDS J005910.90-011401.3, ULAS J133553.45+113005.2, and ULAS J003402.77−005206.7. The spectra of these objects have absorption peaks around 1.55 micrometers. Delorme et al. have suggested that this feature is due to absorption from ammonia and that this should be taken as indicating the T–Y transition, making these objects of type Y0. However, the feature is difficult to distinguish from absorption by water and methane, and other authors have stated that the assignment of class Y0 is premature.

In April 2010, two newly discovered ultracool sub-brown dwarfs (UGPS 0722-05 and SDWFS 1433+35) were proposed as prototypes for spectral class Y0.

In February 2011, Luhman|display-authors=et al reported the

discovery of a "brown dwarf" companion to a nearby white dwarf with a

temperature of c. 300 K and mass of 7 MJ. Though of planetary mass, Rodriguez|display-authors=et al suggest it is unlikely to have formed in the same manner as planets.

Shortly after that, Liu|display-authors=et al published an account of a "very cold" (c. 370 K)

brown dwarf orbiting another very-low-mass brown dwarf and noted that

"Given its low luminosity, atypical colors and cold temperature, CFBDS

J1458+10B is a promising candidate for the hypothesized Y spectral

class."

In August 2011, scientists using data from NASA's Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) discovered six "Y dwarfs"—star-like bodies with temperatures as cool as the human body.

WISE 0458+6434 is the first ultra-cool brown dwarf (green dot) discovered by WISE. The green and blue comes from infrared wavelengths mapped to visible colors.

WISE data has revealed hundreds of new brown dwarfs. Of these, fourteen are classified as cool Ys. One of the Y dwarfs, called WISE 1828+2650,

was, as of August 2011, the record holder for the coldest brown dwarf –

emitting no visible light at all, this type of object resembles

free-floating planets more than stars. WISE 1828+2650 was initially

estimated to have an atmospheric temperature cooler than 300 K—for comparison, the upper end of room temperature

is 298 K (25 °C; 77 °F). Its temperature has since been revised and

newer estimates put it in the range of 250 to 400 K (−23 to 127 °C; −10

to 260 °F).

In April 2014, WISE 0855−0714 was announced with a temperature profile estimated around 225 to 260 K (−48 to −13 °C; −55 to 8 °F) and a mass of 3 to 10 MJ. It was also unusual in that its observed parallax meant a distance close to 7.2±0.7 light years from the Solar System.

Spectral and atmospheric properties of brown dwarfs

The

majority of flux emitted by L and T dwarfs is in the 1 to 2.5

micrometer near-infrared range. Low and decreasing temperatures through

the late M-, L-, and T-dwarf sequence result in a rich near-infrared spectrum

containing a wide variety of features, from relatively narrow lines of

neutral atomic species to broad molecular bands, all of which have

different dependencies on temperature, gravity, and metallicity. Furthermore, these low temperature conditions favor condensation out of the gas state and the formation of grains.

Typical atmospheres of known brown dwarfs range in temperature from 2200 down to 750 K.

Compared to stars, which warm themselves with steady internal fusion,

brown dwarfs cool quickly over time; more massive dwarfs cool more

slowly than less massive ones.

Observational techniques

Brown dwarfs Teide 1, Gliese 229B, and WISE 1828+2650 compared to red dwarf Gliese 229A, Jupiter and our Sun

Coronagraphs have recently been used to detect faint objects orbiting bright visible stars, including Gliese 229B.

Sensitive telescopes equipped with charge-coupled devices (CCDs)

have been used to search distant star clusters for faint objects,

including Teide 1.

Wide-field searches have identified individual faint objects, such as Kelu-1 (30 ly away).

Brown dwarfs are often discovered in surveys to discover extrasolar planets. Methods of detecting extrasolar planets work for brown dwarfs as well, although brown dwarfs are much easier to detect.

Brown dwarfs can be powerful emitters of radio emission due to their strong magnetic fields. Observing programs at the Arecibo Observatory and the Very Large Array have detected over a dozen such objects, which are also called ultracool dwarfs because they share common magnetic properties with other objects in this class. The detection of radio emission from brown dwarfs permits their magnetic field strengths to be measured directly.

Milestones

- 1995: First brown dwarf verified. Teide 1, an M8 object in the Pleiades cluster, is picked out with a CCD in the Spanish Observatory of Roque de los Muchachos of the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias.

First methane brown dwarf verified. Gliese 229B is discovered orbiting red dwarf Gliese 229A (20 ly away) using an adaptive optics coronagraph to sharpen images from the 60-inch (1.5 m) reflecting telescope at Palomar Observatory on Southern California's Mt. Palomar; follow-up infrared spectroscopy made with their 200-inch (5 m) Hale telescope shows an abundance of methane.

- 1998: First X-ray-emitting brown dwarf found. Cha Halpha 1, an M8 object in the Chamaeleon I dark cloud, is determined to be an X-ray source, similar to convective late-type stars.

- 15 December 1999: First X-ray flare detected from a brown dwarf. A team at the University of California monitoring LP 944-20 (60 MJ, 16 ly away) via the Chandra X-ray Observatory, catches a 2-hour flare.

- 27 July 2000: First radio emission (in flare and quiescence) detected from a brown dwarf. A team of students at the Very Large Array detected emission from LP 944-20.

- 25 April 2014: Coldest known brown dwarf discovered. WISE 0855−0714 is 7.2 light-years away (7th closest system to the Sun) and has a temperature between −48 to −13 degrees Celsius.

Brown dwarf as an X-ray source

Chandra image of LP 944-20 before flare and during flare

X-ray flares detected from brown dwarfs since 1999 suggest changing magnetic fields within them, similar to those in very-low-mass stars.

With no strong central nuclear energy source, the interior of a

brown dwarf is in a rapid boiling, or convective state. When combined

with the rapid rotation that most brown dwarfs exhibit, convection sets up conditions for the development of a strong, tangled magnetic field near the surface. The flare observed by Chandra

from LP 944-20 could have its origin in the turbulent magnetized hot

material beneath the brown dwarf's surface. A sub-surface flare could

conduct heat to the atmosphere, allowing electric currents to flow and

produce an X-ray flare, like a stroke of lightning.

The absence of X-rays from LP 944-20 during the non-flaring period is

also a significant result. It sets the lowest observational limit on

steady X-ray power produced by a brown dwarf, and shows that coronas

cease to exist as the surface temperature of a brown dwarf cools below

about 2800K and becomes electrically neutral.

Using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, scientists have detected X-rays from a low-mass brown dwarf in a multiple star system. This is the first time that a brown dwarf this close to its parent star(s) (Sun-like stars TWA 5A) has been resolved in X-rays.

"Our Chandra data show that the X-rays originate from the brown dwarf's

coronal plasma which is some 3 million degrees Celsius", said Yohko

Tsuboi of Chuo University in Tokyo.

"This brown dwarf is as bright as the Sun today in X-ray light, while

it is fifty times less massive than the Sun", said Tsuboi. "This observation, thus, raises the possibility that even massive planets might emit X-rays by themselves during their youth!"

Brown dwarfs as radio sources

Brown dwarfs can maintain magnetic fields of up to 6 kG in strength.

Approximately 5-10% of brown dwarfs appear to have strong magnetic

fields and emit radio waves, and there may be as many as 40 magnetic

brown dwarfs within 25 pc of the Sun based on Monte Carlo modeling and their average spatial density.

The regular, periodic reversal of radio wave orientation may indicate

that brown dwarf magnetic fields periodically reverse orientation.

These reversals may be the result of a brown dwarf magnetic activity

cycle, similar to the solar cycle.

Recent developments

The brown dwarf Cha 110913-773444,

located 500 light years away in the constellation Chamaeleon, may be in

the process of forming a miniature planetary system. Astronomers from Pennsylvania State University

have detected what they believe to be a disk of gas and dust similar to

the one hypothesized to have formed the Solar System. Cha 110913-773444

is the smallest brown dwarf found to date (8 MJ), and if it formed a planetary system, it would be the smallest known object to have one.

Recent observations of known brown dwarf candidates have revealed

a pattern of brightening and dimming of infrared emissions that

suggests relatively cool, opaque cloud patterns obscuring a hot interior

that is stirred by extreme winds. The weather on such bodies is thought

to be extremely violent, comparable to but far exceeding Jupiter's

famous storms.

On January 8, 2013 astronomers using NASA's Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes probed the stormy atmosphere of a brown dwarf named 2MASS J22282889-431026,

creating the most detailed "weather map" of a brown dwarf thus far. It

shows wind-driven, planet-sized clouds. The new research is a stepping

stone toward a better understanding not only brown dwarfs, but also of

the atmospheres of planets beyond the Solar System.

NASA's WISE mission has detected 200 new brown dwarfs.

There are actually fewer brown dwarfs in our cosmic neighborhood than

previously thought. Rather than one star for every brown dwarf, there

may be as many as six stars for every brown dwarf.

In a study published in Aug 2017 NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope

monitored infrared brightness variations in brown dwarfs caused by

cloud cover of variable thickness. The observations revealed that

large-scale waves propagating in the atmospheres of brown dwarfs

(similarly to the atmosphere of Neptune and other Solar System giant

planets). These atmospheric waves modulate the thickness of the clouds

and propagate with different velocities (probably due to differential

rotation).

Planets around brown dwarfs

Artist's impression of a disc of dust and gas around a brown dwarf

The super-Jupiter planetary-mass objects 2M1207b and 2MASS J044144 that are orbiting brown dwarfs at large orbital distances may have formed by cloud collapse rather than accretion and so may be sub-brown dwarfs rather than planets,

which is inferred from relatively large masses and large orbits. The

first discovery of a low-mass companion orbiting a brown dwarf (ChaHα8) at a small orbital distance using the radial velocity technique paved the way for the detection of planets around brown dwarfs on orbits of a few AU or smaller. However, with a mass ratio between the companion and primary in ChaHα8

of about 0.3, this system rather resembles a binary star. Then, in

2013, the first planetary-mass companion (OGLE-2012-BLG-0358L b) in a

relatively small orbit was discovered orbiting a brown dwarf.

In 2015, the first terrestrial-mass planet orbiting a brown dwarf was found, OGLE-2013-BLG-0723LBb.

Disks

around brown dwarfs have been found to have many of the same features

as disks around stars; therefore, it is expected that there will be

accretion-formed planets around brown dwarfs. Given the small mass of brown dwarf disks, most planets will be terrestrial planets rather than gas giants.

If a giant planet orbits a brown dwarf across our line of sight, then,

because they have approximately the same diameter, this would give a

large signal for detection by transit.

The accretion zone for planets around a brown dwarf is very close to

the brown dwarf itself, so tidal forces would have a strong effect.

Planets around brown dwarfs are likely to be carbon planets depleted of water.

A 2016 study, based upon observations with Spitzer estimates that

175 brown dwarfs need to be monitored in order to guarantee (95%) at

least one detection of a planet.

Habitability

Habitability

for hypothetical planets orbiting brown dwarfs has been studied.

Computer models suggesting conditions for these bodies to have habitable planets are very stringent, the habitable zone being narrow and decreasing with time, due to the cooling of the brown dwarf. The orbits there would have to be of extremely low eccentricity (of the order of 10−6) to avoid strong tidal forces that would trigger a greenhouse effect on the planets, rendering them uninhabitable.