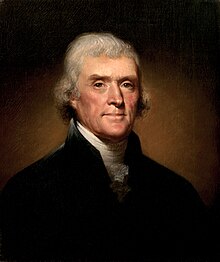

Portrait of Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale in 1800

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson,

was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United

States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The term was commonly used to refer

to the Democratic-Republican Party (formally named the "Republican Party"), which Jefferson founded in opposition to the Federalist Party of Alexander Hamilton. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism,

which meant opposition to what they considered to be artificial

aristocracy, opposition to corruption, and insistence on virtue, with a

priority for the "yeoman farmer", "planters", and the "plain folk".

They were antagonistic to the aristocratic elitism of merchants,

bankers, and manufacturers, distrusted factory workers, and were on the

watch for supporters of the dreaded British system of government.

Jeffersonian democracy persisted as an element of the Democratic Party into the early 20th century, as exemplified by the rise of Jacksonian democracy and the three presidential candidacies of William Jennings Bryan. Its themes continue to echo in the 21st century, particularly among the Libertarian and Republican parties.

At the beginning of the Jeffersonian era, only two states

(Vermont and Kentucky) had established universal white male suffrage by

abolishing property requirements. By the end of the period, more than

half of the states had followed suit, including virtually all of the

states in the Old Northwest.

States then also moved on to allowing popular votes for presidential

elections, canvassing voters in a more modern style. Jefferson's party,

known today as the Democratic-Republican Party, was then in full control

of the apparatus of government—from the state legislature and city hall to the White House.

Positions

Jefferson has been called "the most democratic of the Founding fathers". The Jeffersonians advocated a narrow interpretation of the Constitution's Article I provisions granting powers to the federal government. They strenuously opposed the Federalist Party, led by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. President George Washington generally supported Hamilton's program for a financially strong national government. The election of Jefferson in 1800, which he called "the revolution of 1800", brought in the Presidency of Thomas Jefferson and the permanent eclipse of the Federalists, apart from the Supreme Court.

"Jeffersonian democracy" is an umbrella term and some factions

favored some positions more than others. While principled, with

vehemently held core beliefs, the Jeffersonians had factions that

disputed the true meaning of their creed. For example, during the War of 1812

it became apparent that independent state militia units were inadequate

for conducting a serious war against a major country. The new Secretary

of War John C. Calhoun, a Jeffersonian, proposed to build up the Army. With the support of most Republicans in Congress, he got his way. However, the "Old Republican" faction, claiming to be true to the Jeffersonian Principles of '98, fought him and reduced the size of the Army after Spain sold Florida to the U.S.

Historians characterize Jeffersonian democracy as including the following core ideals:

- The core political value of America is republicanism—citizens have a civic duty to aid the state and resist corruption, especially monarchism and aristocracy.

- Jeffersonian values are best expressed through an organized political party. The Jeffersonian party was officially the "Republican Party" (political scientists later called it the Democratic-Republican Party to differentiate it from the later Republican Party of Lincoln).

- It was the duty of citizens to vote and the Jeffersonians invented many modern campaign techniques designed to get out the vote. Turnout indeed soared across the country. The work of John J. Beckley, Jefferson's agent in Pennsylvania, set new standards in the 1790s. In the 1796 presidential election, he blanketed the state with agents who passed out 30,000 hand-written tickets, naming all 15 electors (printed tickets were not allowed). Historians consider Beckley to be one of the first American professional campaign managers and his techniques were quickly adopted in other states.

- The Federalist Party, especially its leader Alexander Hamilton, was the arch-foe because of its acceptance of aristocracy and British methods.

- The national government is a dangerous necessity to be instituted for the common benefit, protection and security of the people, nation or community—it should be watched closely and circumscribed in its powers. Most anti-Federalists from 1787–1788 joined the Jeffersonians.

- Separation of church and state is the best method to keep government free of religious disputes and religion free from corruption by government.

- The federal government must not violate the rights of individuals. The Bill of Rights is a central theme.

- The federal government must not violate the rights of the states. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions of 1798 (written secretly by Jefferson and James Madison) proclaim these principles.

- Freedom of speech and the press are the best methods to prevent tyranny over the people by their own government. The Federalists' violation of this freedom through the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 became a major issue.

- The yeoman farmer best exemplifies civic virtue and independence from corrupting city influences—government policy should be for his benefit. Financiers, bankers and industrialists make cities the "cesspools of corruption" and should be avoided.

"We the People" in an original edition of the U.S. Constitution

- The United States Constitution was written in order to ensure the freedom of the people. However, as Jefferson wrote to James Madison in 1789, "no society can make a perpetual constitution or even a perpetual law. The earth belongs always to the living generation".

- All men have the right to be informed and thus to have a say in the government. The protection and expansion of human liberty was one of the chief goals of the Jeffersonians. They also reformed their respective state systems of education. They believed that their citizens had a right to an education no matter their circumstance or status in life.

- The judiciary should be subservient to the elected branches and the Supreme Court should not have the power to strike down laws passed by Congress. The Jeffersonians lost this battle to Chief Justice John Marshall, a Federalist, who dominated the Court from 1801 to his death in 1835.

- The Jeffersonians also had a distinct foreign policy:

- Americans had a duty to spread what Jefferson called the "Empire of Liberty" to the world, but should avoid "entangling alliances".

- Britain was the greatest threat, especially its monarchy, aristocracy, corruption and business methods—the Jay Treaty of 1794 was much too favorable to Britain and thus threatened American values.

- At least in the early stages of the French Revolution, France was the ideal European nation. According to Michael Hardt, "Jefferson's support of the French Revolution often serves in his mind as a defense of republicanism against the monarchism of the Anglophiles". On the other hand, Napoleon was the antithesis of republicanism and could not be supported.

- Louisiana and the Mississippi River were critical to American national interests. Control by Spain was tolerable—control by France was unacceptable. See Louisiana Purchase.

- A standing army and navy are dangerous to liberty and should be avoided—much better was to use economic coercion such as the embargo.

- The militia was adequate to defend the nation. During the Revolutionary War previously, a national conflict, in this case the War of 1812, required the creation of a national army for the duration of international hostilities.

Westward expansion

Territorial expansion of the United States

was a major goal of the Jeffersonians because it would produce new farm

lands for yeomen farmers. The Jeffersonians wanted to integrate the

Indians into American society, or remove further west those tribes that

refused to integrate. However Sheehan (1974) argues that the

Jeffersonians, with the best of goodwill toward the Indians, destroyed

their distinctive cultures with its misguided benevolence.

The original treaty of the Louisiana Purchase

The Jeffersonians took enormous pride in the bargain they reached with France in the Louisiana Purchase

of 1803. It opened up vast new fertile farmlands from Louisiana to

Montana. Jefferson saw the West as an economic safety valve which would

allow people in the crowded East to own farms. However, established New England political interests feared the growth of the West and a majority in the Federalist Party opposed the purchase.

Jeffersonians thought the new territory would help maintain their

vision of the ideal republican society, based on agricultural commerce,

governed lightly and promoting self-reliance and virtue.

The Jeffersonians' dream did not come to pass as the Louisiana Purchase was a turning point in the history of American imperialism.

The farmers with whom Jefferson identified conquered the West, often

through violence against Native Americans. Jefferson himself sympathized

with Native Americans, but that did not stop him from enacting policies

that would continue the trend towards the dispossession of their lands.

Economics

Jeffersonian agrarians held that the economy of the United States should rely more on agriculture for strategic commodities than on industry.

Jefferson specifically believed: "Those who labor in the earth are the

chosen people of God, if He ever had a chosen people, whose breast He

has made His peculiar deposit for substantial and genuine virtue".

However, Jeffersonian ideals are not opposed to all manufacturing,

rather he believed that all people have the right to work to provide for

their own subsistence and that an economic system which undermines that

right is unacceptable.

Jefferson's belief was that unlimited expansion of commerce and

industry would lead to the growth of a class of wage laborers who relied

on others for income and sustenance. The workers would no longer be

independent voters. Such a situation, Jefferson feared, would leave the

American people vulnerable to political subjugation and economic

manipulation. The solution Jefferson came up with was, as scholar Clay

Jenkinson noted, "a graduated income tax that would serve as a

disincentive to vast accumulations of wealth and would make funds

available for some sort of benign redistribution downward" as well as

tariffs on imported articles, which were mainly purchased by the

wealthy.

Similarly, Jefferson had protectionist

views on international trade. He believed that not only would economic

dependence on Europe diminish the virtue of the republic, but that the

United States had an abundance of natural resources that Americans

should be able to cultivate and use to tend to their own needs.

Furthermore, exporting goods by merchant ships created risks of capture

by foreign pirates and armies, which would require an expensive navy for

protection.

Lastly, he and other Jeffersonians believed in the power of embargoes

as a means to inflict punishment on hostile foreign nations. Jefferson

preferred these methods of coercion to war.

Limited government

Jefferson's thoughts on limited government were influenced by the 17th century English political philosopher John Locke (pictured).

While the Federalists advocated for a strong central government,

Jeffersonians argued for strong state and local governments and a weak

federal government.

Self-sufficiency, self-government and individual responsibility were in

the Jeffersonian worldview among the most important ideals that formed

the basis of the American Revolution.

In Jefferson's opinion, nothing that could feasibly be accomplished by

individuals at the local level ought to be accomplished by the federal

government. The federal government would concentrate its efforts solely

on national and international projects. Jefferson's advocacy of limited government led to sharp disagreements with Federalist figures such as Alexander Hamilton. Jefferson felt that Hamilton favored plutocracy

and the creation of a powerful aristocracy in the United States which

would accumulate increasingly greater power until the political and

social order of the United States became indistinguishable from those of

the Old World.

After initial skepticism, Jefferson supported the ratification of the United States Constitution and especially supported its stress on checks and balances. The ratification of the United States Bill of Rights, especially the First Amendment, gave Jefferson even greater confidence in the document. Jeffersonians favored a strict construction

interpretation of federal government powers described in Article I of

the Constitution. For example, Jefferson once wrote a letter to Charles Willson Peale

explaining that although a Smithsonian-style national museum would be a

wonderful resource, he could not support the use of federal funds to

construct and maintain such a project. The "strict constructionism" of today is a remote descendant of Jefferson's views.

Politics and factions

The spirit of Jeffersonian democracy dominated American politics from 1800 to 1824, the First Party System, under Jefferson and succeeding presidents James Madison and James Monroe.

The Jeffersonians proved much more successful than the Federalists in

building state and local party organizations that united various

factions. Voters in every state formed blocs loyal to the Jeffersonian coalition.

Prominent spokesmen for Jeffersonian principles included Madison, Albert Gallatin, John Randolph of Roanoke, Nathaniel Macon, John Taylor of Caroline and James Monroe, as well as John C. Calhoun, John Quincy Adams and Henry Clay (with the last three taking new paths after 1828).

Randolph was the Jeffersonian leader in Congress from 1801 to 1815, but he later broke with Jefferson and formed his own "Tertium Quids" faction because he thought the president no longer adhered to the true Jeffersonian principles of 1798.

The Quids wanted to actively punish and discharge Federalists in the

government and in the courts. Jefferson himself sided with the moderate

faction exemplified by figures such as Madison, who were much more

conciliatory towards Federalism.

After the Madison administration experienced serious trouble financing the War of 1812

and discovered the Army and militia were unable to make war

effectively, a new generation of Republican nationalists emerged. They

were supported by President James Monroe, an original Jeffersonian; and included John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. In 1824, Adams defeated Andrew Jackson, who had support from the Quids; and in a few years two successor parties had emerged, the Democratic Party, which formulated Jacksonian democracy and which still exists; and Henry Clay's Whig Party. Their competition marked the Second Party System.

After 1830, the principles were still talked about but did not form the basis of a political party, thus editor Horace Greeley in 1838 started a magazine, The Jeffersonian,

that he said "would exhibit a practical regard for that cardinal

principle of Jeffersonian Democracy, and the People are the sole and

safe depository of all power, principles and opinions which are to

direct the Government".

Jefferson and Jeffersonian principles

Jeffersonian

democracy was not a one-man operation. It was a large political party

with many local and state leaders and various factions, and they did not

always agree with Jefferson or with each other.

Jefferson was accused of inconsistencies by his opponents.

The "Old Republicans" said that he abandoned the Principles of 1798. He

believed the national security concerns were so urgent that it was

necessary to purchase Louisiana without waiting for a Constitutional

amendment. He enlarged federal power through the intrusively-enforced Embargo Act of 1807.

He idealized the "yeoman farmer" despite being himself a gentleman

plantation owner. The disparities between Jefferson's philosophy and

practice have been noted by numerous historians. Staaloff proposed that

it was due to his being a proto-Romantic; John Quincy Adams claimed that it was a manifestation of pure hypocrisy, or "pliability of principle";

and Bailyn asserts it simply represented a contradiction with

Jefferson, that he was "simultaneously a radical utopian idealist and a

hardheaded, adroit, at times cunning politician".

However, Jenkinson argued that Jefferson's personal failings ought not

to influence present day thinkers to disregard Jeffersonian ideals.

Kuehnelt-Leddihn,

a European nobleman who opposed democracy, argues that "Jeffersonian

democracy" is a misnomer because Jefferson was not a democrat, but in

fact believed in rule by an elite: "Jefferson actually was an Agrarian

Romantic who dreamt of a republic governed by an elite of character and

intellect".

Historian Sean Wilentz

argues that as a practical politician elected to serve the people

Jefferson had to negotiate solutions, not insist on his own version of

abstract positions. The result, Wilentz argues, was "flexible responses

to unforeseen events ... in pursuit of ideals ranging from the

enlargement of opportunities for the mass of ordinary, industrious

Americans to the principled avoidance of war".

Historians have long portrayed the contest between Jefferson and

Hamilton as iconic for the politics, political philosophy, economic

policies and future direction of the United States. In 2010, Wilentz identified a scholarly trend in Hamilton's favor:

In recent years, Hamilton and his reputation have decidedly gained the initiative among scholars who portray him as the visionary architect of the modern liberal capitalist economy and of a dynamic federal government headed by an energetic executive. Jefferson and his allies, by contrast, have come across as naïve, dreamy idealists. At best according to many historians, the Jeffersonians were reactionary utopians who resisted the onrush of capitalist modernity in hopes of turning America into a yeoman farmers' arcadia. At worst, they were proslavery racists who wish to rid the West of Indians, expand the empire of slavery, and keep political power in local hands – all the better to expand the institution of slavery and protect slaveholders' rights to own human property.