The Extraction of the Stone of Madness (The Cure of Folly) by Hieronymous Bosch

Surgery is the branch of medicine that deals with the physical manipulation of a bodily structure to diagnose, prevent, or cure an ailment. Ambroise Paré,

a 16th-century French surgeon, stated that to perform surgery is, "To

eliminate that which is superfluous, restore that which has been

dislocated, separate that which has been united, join that which has

been divided and repair the defects of nature."

Since humans first learned to make and handle tools, they have

employed their talents to develop surgical techniques, each time more

sophisticated than the last; however, until the industrial revolution,

surgeons were incapable of overcoming the three principal obstacles

which had plagued the medical profession from its infancy — bleeding, pain and infection.

Advances in these fields have transformed surgery from a risky "art"

into a scientific discipline capable of treating many diseases and

conditions.

Origins

The

first surgical techniques were developed to treat injuries and traumas. A

combination of archaeological and anthropological studies offer insight

into man's early techniques for suturing lacerations, amputating

unsalvageable limbs, and draining and cauterizing open wounds. Many

examples exist: some Asian tribes used a mix of saltpeter and sulfur

that was placed onto wounds and lit on fire to cauterize wounds; the

Dakota people used the quill of a feather attached to an animal bladder

to suck out purulent material; the discovery of needles from the stone

age seem to suggest they were used in the suturing of cuts (the Maasai used needles of acacia

for the same purpose); and tribes in India and South America developed

an ingenious method of sealing minor injuries by applying termites or

scarabs who bit the edges of the wound and then twisted the insects'

neck, leaving their heads rigidly attached like staples.

Trepanation

The oldest operation for which evidence exists is trepanation (also known as trepanning, trephination, trephining or burr hole from Greek τρύπανον and τρυπανισμός), in which a hole is drilled or scraped into the skull for exposing the dura mater

to treat health problems related to intracranial pressure and other

diseases. In the case of head wounds, surgical intervention was

implemented for investigating and diagnosing the nature of the wound and

the extent of the impact while bone splinters were removed preferably

by scraping followed by post operation procedures and treatments for

avoiding infection and aiding in the healing process. Evidence has been found in prehistoric human remains from Proto-Neolithic and Neolithic times, in cave paintings, and the procedure continued in use well into recorded history (being described by ancient Greek writers such as Hippocrates). Out of 120 prehistoric skulls found at one burial site in France dated to 6500 BCE, 40 had trepanation holes. Folke Henschen, a Swedish doctor and historian, asserts that Soviet excavations of the banks of the Dnieper River in the 1970s show the existence of trepanation in Mesolithic times dated to approximately 12000 BCE. The remains suggest a belief that trepanning could cure epileptic seizures, migraines, and certain mental disorders.

There is significant evidence of healing of the bones of the

skull in prehistoric skeletons, suggesting that many of those that

proceeded with the surgery survived their operation. In some studies, the rate of survival surpassed 50%.

Setting bones

Examples

of healed fractures in prehistoric human bones, suggesting setting and

splinting have been found in the archeological record.

Among some treatments used by the Aztecs,

according to Spanish texts during the conquest of Mexico, was the

reduction of fractured bones: "...the broken bone had to be splinted,

extended and adjusted, and if this was not sufficient an incision was

made at the end of the bone, and a branch of fir was inserted into the cavity of the medulla..." Modern medicine developed a technique similar to this in the 20th century known as medullary fixation.

Bloodletting

Hirudo medicinalis. Leeches for bloodletting

Bloodletting is one of the oldest medical practices, having been practiced among diverse ancient peoples, including the Mesopotamians, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Mayans,

and the Aztecs. In Greece, bloodletting was in use around the time of

Hippocrates, who mentions bloodletting but in general relied on dietary

techniques. Erasistratus,

however, theorized that many diseases were caused by plethoras, or

over abundances, in the blood, and advised that these plethoras be

treated, initially, by exercise, sweating, reduced food intake, and

vomiting. Herophilus advocated bloodletting. Archagathus,

one of the first Greek physicians to practice in Rome, practiced

bloodletting extensively. The art of bloodletting became very popular in

the West, and during the Renaissance

one could find bloodletting calendars that recommended appropriate

times to bloodlet during the year and books that claimed bloodletting

would cure inflammation, infections, strokes, manic psychosis and more.

Antiquity

Mesopotamia

The

Sumerians saw sickness as a divine punishment imposed by different

demons when an individual broke a rule. For this reason, to be a

physician, one had to learn to identify approximately 6,000 possible

demons that might cause health problems. To do this, the Sumerians

employed divining techniques based on the flight of birds, position of

the stars and the livers of certain animals. In this way, medicine was

intimately linked to priests, relegating surgery to a second-class

medical specialty.

Nevertheless, the Sumerians developed several important medical techniques: in Ninevah

archaeologists have discovered bronze instruments with sharpened

obsidian resembling modern day scalpels, knives, trephines, etc. The Code of Hammurabi,

one of the earliest Babylonian code of laws, itself contains specific

legislation regulating surgeons and medical compensation as well as

malpractice and victim's compensation:

215. If a physician make a large incision with an operating knife and cure it, or if he open a tumor (over the eye) with an operating knife, and saves the eye, he shall receive ten shekels in money.

217. If he be the slave of some one, his owner shall give the physician two shekels.

218. If a physician make a large incision with the operating knife, and kill him, or open a tumor with the operating knife, and cut out the eye, his hands shall be cut off.

220. If he had opened a tumor with the operating knife, and put out his eye, he shall pay half his value.

Egypt

Pictures of surgery tools at Kom Ombo, Egypt

Around 3100 BCE Egyptian civilization began to flourish when Narmer, the first Pharaoh of Egypt, established the capital of Memphis. Just as cuneiform tablets preserved the knowledge of the ancient Sumerians, hieroglyphics preserved the Egyptian's.

In the first monarchic age (2700 BCE) the first treaty on surgery was written by Imhotep, the vizier of Pharaoh Djoser,

priest, astronomer, physician and first notable architect. So much was

he famed for his medical skill that he became the Egyptian god of

medicine. Other famous physicians from the Ancient Empire (from 2500 to 2100 BCE) were Sachmet, the physician of Pharaoh Sahure and Nesmenau, whose office resembled that of a medical director.

On one of the doorjambs of the entrance to the Temple of Memphis there is the oldest recorded engraving of a medical procedure: circumcision and engravings in Kom Ombo,

Egypt depict surgical tools. Still of all the discoveries made in

ancient Egypt, the most important discovery relating to ancient Egyptian

knowledge of medicine is the Ebers Papyrus, named after its discoverer Georg Ebers.

The Ebers Papyrus, conserved at the University of Leipzig, is considered one of the oldest treaties on medicine and the most important medical papyri.

The text is dated to about 1550 BCE and measures 20 meters in length.

The text includes recipes, a pharmacopoeia and descriptions of numerous

diseases as well as cosmetic treatments. It mentions how to surgically

treat crocodile bites and serious burns, recommending the drainage of

pus-filled inflammation but warns against certain diseased skin.

Edwin Smith Papyrus

Plates vi and vii of the Edwin Smith Papyrus (around the 17th century BC), among the earliest medical texts

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is a lesser known papyrus dating from the

1600 BCE and only 5 meters in length. It is a manual for performing

traumatic surgery and gives 48 case histories. The Smith Papyrus describes a treatment for repairing a broken nose, and the use of sutures to close wounds. Infections were treated with honey. For example, it gives instructions for dealing with a dislocated vertebra:

Thou shouldst bind it with fresh meat the first day. Thou shouldst loose his bandages and apply grease to his head as far as his neck, (and) thou shouldst bind it with ymrw . Thou shouldst treat it afterwards with honey every day, (and) his relief is sitting until he recovers.

India

Archaeologists made the discovery that the people of Indus Valley Civilization, even from the early Harappan periods (c. 3300 BCE),

had knowledge of medicine and dentistry. The physical anthropologist

that carried out the examinations, Professor Andrea Cucina from the

University of Missouri-Columbia, made the discovery when he was cleaning

the teeth from one of the men. Later research in the same area found

evidence of teeth having been drilled, dating back 9,000 years to 7000

BCE.

Sushruta (c. 600 BCE) is considered as the "founding father of surgery". His period is usually placed between the period of 1200 BC - 600 BC. One of the earliest known mention of the name is from the Bower Manuscript where Sushruta is listed as one of the ten sages residing in the Himalayas. Texts also suggest that he learned surgery at Kasi from Lord Dhanvantari, the god of medicine in Hindu mythology. He was an early innovator of plastic surgery who taught and practiced surgery on the banks of the Ganges in the area that corresponds to the present day city of Varanasi in Northern India. Much of what is known about Sushruta is in Sanskrit contained in a series of volumes he authored, which are collectively known as the Sushruta Samhita.

It is one of the oldest known surgical texts and it describes in detail

the examination, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of numerous

ailments, as well as procedures on performing various forms of cosmetic

surgery, plastic surgery and rhinoplasty.

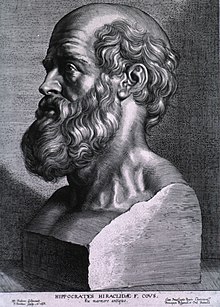

Greece and the Hellenized world

Engraving of Hippocrates by Peter Paul Rubens, 1638.

Surgeons are now considered to be specialized physicians, whereas in the early ancient Greek world a trained general physician had to use his hands (χείρ in Greek)

to carry out all medical and medicinal processes including for example

the treating of wounds sustained on the battlefield, or the treatment of

broken bones (a process called in Greek: χειρουργείν).

In The Iliad Homer names two doctors, “the two sons of Asklepios, the admirable physicians Podaleirius and Machaon and one acting doctor, Patroclus. Because Machaon is wounded and Podaleirius is in combat Eurypylus

asks Patroclus “to cut out this arrow from my thigh, wash off the blood

with warm water and spread soothing ointment on the wound."

Hippocrates

The Hippocratic Oath,

written in the 5th century BC provides the earliest protocol for

professional conduct and ethical behavior a young physician needed to

abide by in life and in treating and managing the health and privacy of

his patients. The multiple volumes of the Hippocratic corpus and the Hippocratic Oath

elevated and separated the standards of proper Hippocratic medical

conduct and its fundamental medical and surgical principles from other

practitioners of folk medicine often laden with superstitious

constructs, and/or of specialists of sorts some of whom would endeavor

to carry out invasive body procedures with dubious consequences, such as

lithotomy. Works from the Hippocratic corpus include; On the Articulations or On Joints, On Fractures, On the Instruments of Reduction, The Physician's Establishment or Surgery, On Injuries of the Head, On Ulcers, On Fistulae, and On Hemorrhoids.

Celsus and Alexandria

Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Ceos were two great Alexandrians who laid the foundations for the scientific study of anatomy and physiology.

Alexandrian surgeons were responsible for developments in ligature

(hemostasis), lithotomy, hernia operations, ophthalmic surgery, plastic

surgery, methods of reduction of dislocations and fractures,

tracheotomy, and mandrake as anesthesia. Most of what we know of them

comes from Celsus and Galen of Pergamum (Greek: Γαληνός)

Galen

Galen's

On the Natural Faculties, Books I, II, and III, is an excellent

paradigm of a very accomplished Greek surgeon and physician of the 2nd

century Roman era,

who carried out very complex surgical operations and added

significantly to the corpus of animal and human physiology and the art

of surgery. He was one of the first to use ligatures in his experiments on animals. Galen is also known as "The king of the catgut suture"

China

In China, instruments resembling surgical tools have also been found in the archaeological sites of Bronze Age dating from the Shang Dynasty, along with seeds likely used for herbalism.

Hua Tuo

Woodblock printing by Utagawa Kuniyoshi of Hua Tuo

Hua Tuo (140–208) was a famous Chinese physician during the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms era. He was the first person to perform surgery with the aid of anesthesia, some 1600 years before the practice was adopted by Europeans. Bian Que (Pien Ch'iao) was a "miracle doctor" described by the Chinese historian Sima Qian in his Shiji who was credited with many skills. Another book, Liezi (Lieh Tzu) describes that Bian Que conducted a two way exchange of hearts between people.

This account also credited Bian Que with using general anesthesia

which would place it far before Hua Tuo, but the source in Liezi is

questioned and the author may have been compiling stories from other

works. Nonetheless, it establishes the concept of heart transplantation back to around 300 CE.

Middle Ages

Paul of Aegina's (c. 625 – c. 690 CE) Pragmateia or Compendiem was highly influential. Abulcasis repeats the material, largely verbatim.

Hunayn ibn Ishaq (809–873) was an Arab Nestorian Christian physician who translated many Greek medical and scientific texts, including those of Galen, writing the first systematic treatment of ophthalmology.

Persian physician Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi (854–925), "the Islamic Hippocrates" advanced experimental medicine, pioneering ophthalmology and founding pediatrics.

In the 9th century the Medical School of Salerno in southwest Italy was founded, making use of Arabic texts and flourishing through the 13th century.

Egypt-born Jewish physician Isaac Israeli ben Solomon

(832–892) left many medical works written in Arabic that were

translated and adopted by European universities in the early 13th

century.

Persian physician Ali ibn Abbas al-Majusi (d. 994) worked at the Al-Adudi Hospital in Baghdad, leaving The Complete Book of the Medical Art, which stressed the need for medical ethics and discussed the anatomy and physiology of the human brain.

Abulcasis (936–1013) (Abu al-Qasim Khalaf ibn al-Abbas Al-Zahrawi) was an Andalusian-Arab physician and scientist who practised in the Zahra suburb of Cordoba. He is considered a great medieval surgeon, though he added little to Greek surgical practices. His works on surgery were influential.

Persian physician Avicenna (980–1037) wrote The Canon of Medicine, a synthesis of Greek and Arab medicine that dominated European medicine until the mid-17th century.

African-born Italian Benedictine monk (Muslim convert) Constantine the African (died 1099) of Monte Cassino translated many Arabic medical works into Latin.

Spanish Muslim physician Avenzoar (1094–1162) performed the first tracheotomy on a goat, writing Book of Simplification on Therapeutics and Diet, which became popular in Europe.

Spanish Muslim physician Averroes (1126–1198) was the first to explain the function of the retina and to recognize acquired immunity with smallpox.

In the late 12th century Rogerius Salernitanus composed his Chirurgia, laying the foundation for modern Western surgical manuals. Roland of Parma and Surgery of the Four Masters were responsible for spreading Roger's work to Italy, France, and England. Roger seems to have been influenced more by the 6th-century Aëtius and Alexander of Tralles, and the 7th-century Paul of Aegina, than by the Arabs. Hugh of Lucca (1150−1257) founded the Bologna School and rejected the theory of "laudable pus".

In the 13th century in Europe skilled town craftsmen called barber-surgeons performed amputations and set broken bones while suffering lower status than university educated doctors. By 1308 the Worshipful Company of Barbers

in London was flourishing. With little or no formal training, they

generally had a bad reputation that was not to improve until the

development of academic surgery as a specialty of medicine rather than

an accessory field in the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment.

Guy de Chauliac (1298–1368) was one of the most eminent surgeons of the Middle Ages. His Chirurgia Magna or Great Surgery (1363) was a standard text for surgeons until well into the seventeenth century."

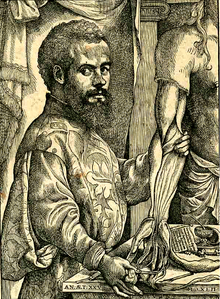

Early modern Europe

Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564)

Ambroise Paré (c. 1510–1590), father of modern military surgery.

Wilhelm Fabry (1540–1634), father of German surgery

There were some important advances to the art of surgery during this period. Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564), professor of anatomy at the University of Padua was a pivotal figure in the Renaissance transition from classical medicine and anatomy based on the works of Galen, to an empirical approach of 'hands-on' dissection. His anatomic treatise De humani corporis fabrica

exposed many anatomical errors in Galen and advocated that all surgeons

should train by engaging in practical dissections themselves.

The second figure of importance in this era was Ambroise Paré (sometimes spelled "Ambrose" (c. 1510 – 1590)),

a French army surgeon from the 1530s until his death in 1590. The

practice for cauterizing gunshot wounds on the battlefield had been to

use boiling oil, an extremely dangerous and painful procedure. Paré

began to employ a less irritating emollient, made of egg yolk, rose oil and turpentine. He also described more efficient techniques for the effective ligation of the blood vessels during an amputation.

Another important early figure was German surgeon Wilhelm Fabry

(1540–1634), "the Father of German Surgery", who was the first to

recommend amputation above the gangrenous area, and to describe a

windlass (twisting stick) tourniquet. His Swiss wife and assistant

Marie Colinet (1560–1640 improved the techniques for Caesarean Section,

introducing the use of heat for dilating and stimulating the uterus

during labor. In 1624 she became the first to use a magnet to remove

metal from a patient's eye, although he received the credit.

Modern surgery

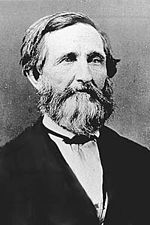

Scientific surgery

John Hunter (1728–1793), father of modern scientific surgery

Benjamin Bell (1749–1806) by Sir Henry Raeburn. c1780

The discipline of surgery was put on a sound, scientific footing during the Age of Enlightenment in Europe (1715–89). An important figure in this regard was the Scottish surgical scientist (in London) John Hunter (1728–1793), generally regarded as the father of modern scientific surgery. He brought an empirical and experimental

approach to the science and was renowned around Europe for the quality

of his research and his written works. Hunter reconstructed surgical

knowledge from scratch; refusing to rely on the testimonies of others he

conducted his own surgical experiments to determine the truth of the

matter. To aid comparative analysis, he built up a collection of over

13,000 specimens of separate organ systems, from the simplest plants and

animals to humans.

Hunter greatly advanced knowledge of venereal disease and introduced many new techniques of surgery, including new methods for repairing damage to the Achilles tendon and a more effective method for applying ligature of the arteries in case of an aneurysm. He was also one of the first to understand the importance of pathology, the danger of the spread of infection and how the problem of inflammation of the wound, bone lesions and even tuberculosis

often undid any benefit that was gained from the intervention. He

consequently adopted the position that all surgical procedures should be

used only as a last resort.

Hunter's student Benjamin Bell

(1749–1806) became the first scientific surgeon in Scotland, advocating

the routine use of opium in post-operative recovery, and counseling

surgeons to "save skin" to speed healing; his great-grandson Joseph Bell (1837–1911) became the inspiration for Arthur Conan Doyle's literary hero Sherlock Holmes.

Percivall Pott (1714–1788), engraved from an original picture by Nathaniel Dance-Holland, National Library of Medicine, Images from the History of Medicine.

Other important 18th- and early 19th-century surgeons included Percival Pott (1714–1788), who first described tuberculosis on the spine and first demonstrated that a cancer may be caused by an environmental carcinogen after he noticed a connection between chimney sweep's exposure to soot and their high incidence of scrotal cancer. Astley Paston Cooper (1768–1841) first performed a successful ligation of the abdominal aorta. James Syme (1799–1870) pioneered the Symes Amputation for the ankle joint and successfully carried out the first hip disarticulation. Dutch surgeon Antonius Mathijsen invented the Plaster of Paris cast in 1851.

Anesthesia

Crawford Long (1815–1878)

James Young Simpson (1811–1870)

John Snow (1813–1858)

Modern pain control through anesthesia was discovered in the mid-19th century. Before the advent of anesthesia, surgery was a traumatically painful procedure and surgeons were encouraged to be as swift as possible to minimize patient suffering. This also meant that operations were largely restricted to amputations and external growth removals.

Beginning in the 1840s, surgery began to change dramatically in

character with the discovery of effective and practical anesthetic

chemicals such as ether, first used by the American surgeon Crawford Long (1815–1878), and chloroform, discovered by James Young Simpson (1811–1870) and later pioneered in England by John Snow (1813–1858), physician to Queen Victoria, who in 1853 administered chloroform to her during childbirth, and in 1854 disproved the miasma theory of contagion by tracing a cholera outbreak in London to an infected water pump.

In addition to relieving patient suffering, anesthesia allowed more

intricate operations in the internal regions of the human body. In

addition, the discovery of muscle relaxants such as curare allowed for safer applications. American surgeon J. Marion Sims (1813–83) received credit for helping found Gynecology, but later was criticized for failing to use anesthesia on African test subjects.

Antiseptic surgery

Joseph Lister, pioneer of antiseptic surgery.

The introduction of anesthetics encouraged more surgery, which

inadvertently caused more dangerous patient post-operative infections.

The concept of infection was unknown until relatively modern times. The

first progress in combating infection was made in 1847 by the Hungarian doctor Ignaz Semmelweis

who noticed that medical students fresh from the dissecting room were

causing excess maternal death compared to midwives. Semmelweis, despite

ridicule and opposition, introduced compulsory hand washing for everyone

entering the maternal wards and was rewarded with a plunge in maternal

and fetal deaths, however the Royal Society dismissed his advice.

Until the pioneering work of British surgeon Joseph Lister in the 1860s, most medical men believed that chemical damage from exposures to bad air was responsible for infections in wounds, and facilities for washing hands or a patient's wounds were not available. Lister became aware of the work of French chemist Louis Pasteur, who showed that rotting and fermentation could occur under anaerobic conditions if micro-organisms were present. Pasteur suggested three methods to eliminate the micro-organisms responsible for gangrene: filtration, exposure to heat, or exposure to chemical solutions. Lister confirmed Pasteur's conclusions with his own experiments and decided to use his findings to develop antiseptic

techniques for wounds. As the first two methods suggested by Pasteur

were inappropriate for the treatment of human tissue, Lister

experimented with the third, spraying carbolic acid on his instruments. He found that this remarkably reduced the incidence of gangrene and he published his results in The Lancet. Later, on 9 August 1867, he read a paper before the British Medical Association in Dublin, on the Antiseptic Principle of the Practice of Surgery, which was reprinted in The British Medical Journal.

His work was groundbreaking and laid the foundations for a rapid

advance in infection control that saw modern antiseptic operating

theaters widely used within 50 years.

Lister continued to develop improved methods of antisepsis and asepsis

when he realized that infection could be better avoided by preventing

bacteria from getting into wounds in the first place. This led to the

rise of sterile surgery. Lister instructed surgeons under his

responsibility to wear clean gloves and wash their hands in 5% carbolic

solution before and after operations, and had surgical instruments

washed in the same solution. He also introduced the steam sterilizer to sterilize

equipment. His discoveries paved the way for a dramatic expansion to

the capabilities of the surgeon; for his contributions he is often

regarded as the father of modern surgery.

These three crucial advances - the adoption of a scientific methodology

toward surgical operations, the use of anaesthetic and the introduction

of sterilized equipment - laid the groundwork for the modern invasive

surgical techniques of today.

In the late 19th century William Stewart Halstead (1852–1922) laid out basic surgical principles for asepsis known as Halsteads principles. Halsted also introduced the latex medical glove.

After one of his nurses suffered skin damage due to having to sterilize

her hands with carbolic acid, Halsted had a rubber glove that could be

dipped in carbolic acid designed.

X-rays

Wilhelm Roentgen (1845–1925)

The use of X-rays as an important medical diagnostic tool began with their discovery in 1895 by German physicist Wilhelm Röntgen. He noticed that these rays could penetrate the skin, allowing the skeletal structure to be captured on a specially treated photographic plate.

Modern technologies

In the past century, a number of technologies have had a significant impact on surgical practice. These include Electrosurgery in the early 20th century, practical Endoscopy beginning in the 1960s, and Laser surgery, Computer-assisted surgery and Robotic surgery, developed in the 1980s.