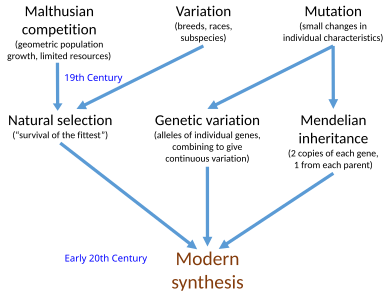

Several major ideas about evolution came together in the population genetics of the early 20th century to form the modern synthesis, including genetic variation, natural selection, and particulate (Mendelian) inheritance. This ended the eclipse of Darwinism and supplanted a variety of non-Darwinian theories of evolution.

The modern synthesis was the early 20th-century synthesis reconciling Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and Gregor Mendel's ideas on heredity in a joint mathematical framework. Julian Huxley coined the term in his 1942 book, Evolution: The Modern Synthesis.

The 19th century ideas of natural selection and Mendelian genetics were put together with population genetics, early in the twentieth century. The modern synthesis also addressed the relationship between the broad-scale changes of macroevolution seen by palaeontologists and the small-scale microevolution of local populations of living organisms. The synthesis was defined differently by its founders, with Ernst Mayr in 1959, G. Ledyard Stebbins in 1966 and Theodosius Dobzhansky

in 1974 offering differing numbers of basic postulates, though they all

included natural selection, working on heritable variation supplied by

mutation. Other major figures in the synthesis included E. B. Ford, Bernhard Rensch, Ivan Schmalhausen, and George Gaylord Simpson. An early event in the modern synthesis was R. A. Fisher's 1918 paper on mathematical population genetics, but William Bateson, and separately Udny Yule, were already starting to show how Mendelian genetics could work in evolution in 1902.

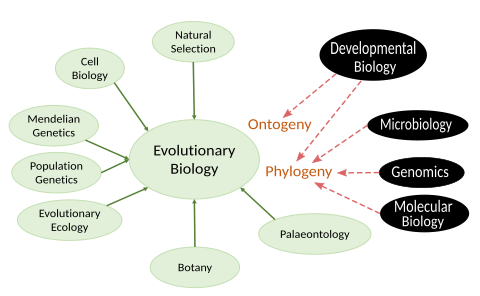

Different syntheses followed, accompanying the gradual breakup of the early 20th century synthesis, including with social behaviour in E. O. Wilson's sociobiology in 1975, evolutionary developmental biology's integration of embryology with genetics and evolution, starting in 1977, and Massimo Pigliucci's proposed extended evolutionary synthesis of 2007. In the view of the evolutionary biologist Eugene Koonin in 2009, the modern synthesis will be replaced by a 'post-modern' synthesis that will include revolutionary changes in molecular biology, the study of prokaryotes and the resulting tree of life, and genomics.

Developments leading up to the synthesis

Darwin's pangenesis theory. Every part of the body emits tiny gemmules which migrate to the gonads

and contribute to the next generation via the fertilised egg. Changes

to the body during an organism's life would be inherited, as in Lamarckism.

Darwin's evolution by natural selection, 1859

Charles Darwin's 1859 book On the Origin of Species was successful in convincing most biologists that evolution had occurred, but was less successful in convincing them that natural selection was its primary mechanism. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, variations of Lamarckism (inheritance of acquired characteristics), orthogenesis (progressive evolution), saltationism (evolution by jumps) and mutationism (evolution driven by mutations) were discussed as alternatives. Alfred Russel Wallace advocated a selectionist version of evolution, and unlike Darwin completely rejected Lamarckism. In 1880, Wallace's view was labelled neo-Darwinism by Samuel Butler.

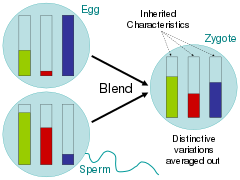

Blending inheritance, implied by pangenesis, causes the averaging out of every characteristic, which as the engineer Fleeming Jenkin pointed out, would make evolution by natural selection impossible.

The eclipse of Darwinism, 1880s onwards

From the 1880s onward, there was a widespread belief among biologists that Darwinian evolution was in deep trouble. This eclipse of Darwinism (in Julian Huxley's

phrase) grew out of the weaknesses in Darwin's account, written with an

incorrect view of inheritance. Darwin himself believed in blending inheritance, which implied that any new variation, even if beneficial, would be weakened by 50% at each generation, as the engineer Fleeming Jenkin correctly noted in 1868.

This in turn meant that small variations would not survive long enough

to be selected. Blending would therefore directly oppose natural

selection. In addition, Darwin and others considered Lamarckian

inheritance of acquired characteristics entirely possible, and Darwin's

1868 theory of pangenesis,

with contributions to the next generation (gemmules) flowing from all

parts of the body, actually implied Lamarckism as well as blending.

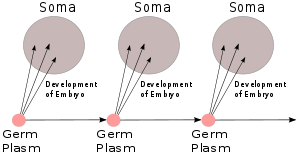

August Weismann's germ plasm theory. The hereditary material, the germ plasm, is confined to the gonads and the gametes. Somatic cells (of the body) develop afresh in each generation from the germ plasm.

Weismann's germ plasm, 1892

August Weismann's idea, set out in his 1892 book Das Keimplasma: eine Theorie der Vererbung (The Germ Plasm: a Theory of Inheritance), was that the hereditary material, which he called the germ plasm, and the rest of the body (the soma)

had a one-way relationship: the germ-plasm formed the body, but the

body did not influence the germ-plasm, except indirectly in its

participation in a population subject to natural selection. If correct,

this made Darwin's pangenesis wrong, and Lamarckian inheritance

impossible. His experiment on mice, cutting off their tails and showing

that their offspring had normal tails, demonstrated that inheritance was

'hard'. He argued strongly and dogmatically

for Darwinism and against Lamarckism, polarizing opinions among other

scientists. This increased anti-Darwinian feeling, contributing to its

eclipse.

Disputed beginnings

Genetics, mutationism and biometrics, 1900–1918

William Bateson championed Mendelism.

While carrying out breeding experiments to clarify the mechanism of inheritance in 1900, Hugo de Vries and Carl Correns independently rediscovered Gregor Mendel's work. News of this reached William Bateson in England, who reported on the paper during a presentation to the Royal Horticultural Society in May 1900. In Mendelian inheritance,

the contributions of each parent retain their integrity rather than

blending with the contribution of the other parent. In the case of a

cross between two true-breeding varieties such as Mendel's round and

wrinkled peas, the first-generation offspring are all alike, in this

case all round. Allowing these to cross, the original characteristics

reappear (segregation): about 3/4 of their offspring are round, 1/4

wrinkled. There is a discontinuity between the appearance of the

offspring; de Vries coined the term allele for a variant form of an inherited characteristic.

This reinforced a major division of thought, already present in the

1890s, between gradualists who followed Darwin, and saltationists such

as Bateson.

The two schools were the Mendelians, such as Bateson and de

Vries, who favored mutationism, evolution driven by mutation, based on

genes whose alleles segregated discretely like Mendel's peas; and the biometric school, led by Karl Pearson and Walter Weldon.

The biometricians argued vigorously against mutationism, saying that

empirical evidence indicated that variation was continuous in most

organisms, not discrete as Mendelism seemed to predict; they wrongly

believed that Mendelism inevitably implied evolution in discontinuous

jumps.

Karl Pearson led the biometric school.

A traditional view is that the biometricians and the Mendelians

rejected natural selection and argued for their separate theories for 20

years, the debate only resolved by the development of population

genetics.

A more recent view is that Bateson, de Vries, Thomas Hunt Morgan and Reginald Punnett

had by 1918 formed a synthesis of Mendelism and mutationism. The

understanding achieved by these geneticists spanned the action of

natural selection on alleles (alternative forms of a gene), the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium,

the evolution of continuously-varying traits (like height), and the

probability that a new mutation will become fixed. In this view, the

early geneticists accepted natural selection but rejected Darwin's

non-Mendelian ideas about variation and heredity, and the synthesis

began soon after 1900.

The traditional claim that Mendelians rejected the idea of continuous

variation is false; as early as 1902, Bateson and Saunders wrote that

"If there were even so few as, say, four or five pairs of possible

allelomorphs, the various homo- and hetero-zygous combinations might, on

seriation, give so near an approach to a continuous curve, that the

purity of the elements would be unsuspected". Also in 1902, the statistician Udny Yule

showed mathematically that given multiple factors, Mendel's theory

enabled continuous variation. Yule criticized Bateson's approach as

confrontational, but failed to prevent the Mendelians and the biometricians from falling out.

Castle's hooded rats, 1911

Starting in 1906, William Castle carried out a long study of the effect of selection on coat colour in rats. The piebald or hooded pattern was recessive

to the grey wild type. He crossed hooded rats with the black-backed

Irish type, and then back-crossed the offspring with pure hooded rats.

The dark stripe on the back was bigger. He then tried selecting

different groups for bigger or smaller stripes for 5 generations, and

found that it was possible to change the characteristics way beyond the

initial range of variation. This effectively refuted de Vries's claim

that continuous variation was caused by the environment and could not be

inherited. By 1911 Castle noted that the results could be explained by

Darwinian selection on heritable variation of a sufficient number of

Mendelian genes.

Morgan's fruit flies, 1912

Thomas Hunt Morgan began his career in genetics as a saltationist,

and started out trying to demonstrate that mutations could produce new

species in fruit flies. However, the experimental work at his lab with

the fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster

demonstrated that rather than creating new species in a single step,

mutations increased the supply of genetic variation in the population.

By 1912, after years of work on the genetics of fruit flies, Morgan

showed that these insects had many small Mendelian factors (discovered

as mutant flies) on which Darwinian evolution could work as if variation

was fully continuous. The way was open for geneticists to conclude that

Mendelism supported Darwinism.

An obstruction: Woodger's positivism, 1929

The theoretical biologist and philosopher of biology Joseph Henry Woodger led the introduction of positivism into biology with his 1929 book Biological Principles. He saw a mature science as being characterized by a framework of hypotheses that could be verified by facts established by experiments. He criticized the traditional natural history style of biology, including the study of evolution, as immature science, since it relied on narrative. Woodger set out to play for biology the role of Robert Boyle's 1661 Sceptical Chymist, intending to convert the subject into a formal, unified science, and ultimately, following the Vienna Circle of logical positivists like Otto Neurath and Rudolf Carnap, to reduce biology to physics and chemistry. His efforts stimulated the biologist J. B. S. Haldane

to push for the axiomatization of biology, and by influencing thinkers

such as Huxley, helped to bring about the modern synthesis.

The positivist climate made natural history unfashionable, and in

America, research and university-level teaching on evolution declined

almost to nothing by the late 1930s. The Harvard physiologist William John Crozier told his students that evolution was not even a science: "You can't experiment with two million years!"

The tide of opinion turned with the adoption of mathematical modelling and controlled experimentation in population genetics, combining genetics, ecology and evolution in a framework acceptable to positivism.

Events in the synthesis

Fisher and Haldane's mathematical population genetics, 1918–1930

In 1918, R. A. Fisher wrote the paper "The Correlation between Relatives on the Supposition of Mendelian Inheritance," which showed mathematically how continuous variation could result from a number of discrete genetic loci. In this and subsequent papers culminating in his 1930 book The Genetical Theory of Natural Selection, Fisher showed how Mendelian genetics was consistent with the idea of evolution driven by natural selection.

During the 1920s, a series of papers by J. B. S. Haldane applied mathematical analysis to real-world examples of natural selection, such as the evolution of industrial melanism in peppered moths. Haldane established that natural selection could work even faster than Fisher had assumed.

Both workers, and others such as Dobzhansky and Wright, explicitly

intended to bring biology up to the philosophical standard of the

physical sciences, making it firmly based in mathematical modelling, its

predictions confirmed by experiment. Natural selection, once considered

hopelessly unverifiable speculation about history, was becoming

predictable, measurable, and testable.

De Beer's embryology, 1930

The traditional view is that developmental biology played little part in the modern synthesis, but in his 1930 book Embryos and Ancestors, the evolutionary embryologist Gavin de Beer anticipated evolutionary developmental biology by showing that evolution could occur by heterochrony, such as in the retention of juvenile features in the adult. This, de Beer argued, could cause apparently sudden changes in the fossil record,

since embryos fossilize poorly. As the gaps in the fossil record had

been used as an argument against Darwin's gradualist evolution, de

Beer's explanation supported the Darwinian position.

However, despite de Beer, the modern synthesis largely ignored embryonic

development to explain the form of organisms, since population genetics

appeared to be an adequate explanation of how forms evolved.

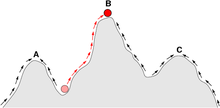

Wright's adaptive landscape, 1932

Sewall Wright introduced the idea of a fitness landscape with local optima.

The population geneticist Sewall Wright focused on combinations of genes that interacted as complexes, and the effects of inbreeding on small relatively isolated populations, which could be subject to genetic drift. In a 1932 paper, he introduced the concept of an adaptive landscape

in which phenomena such as cross breeding and genetic drift in small

populations could push them away from adaptive peaks, which would in

turn allow natural selection to push them towards new adaptive peaks.

Wright's model would appeal to field naturalists such as Theodosius

Dobzhansky and Ernst Mayr who were becoming aware of the importance of

geographical isolation in real world populations. The work of Fisher, Haldane and Wright helped to found the discipline of theoretical population genetics.

Dobzhansky's evolutionary genetics, 1937

Drosophila pseudoobscura, the fruit fly which served as Theodosius Dobzhansky's model organism

Theodosius Dobzhansky, an emigrant from the Soviet Union to the United States,

who had been a postdoctoral worker in Morgan's fruit fly lab, was one

of the first to apply genetics to natural populations. He worked mostly

with Drosophila pseudoobscura.

He says pointedly: "Russia has a variety of climates from the Arctic to

sub-tropical... Exclusively laboratory workers who neither possess nor

wish to have any knowledge of living beings in nature were and are in a

minority." Not surprisingly, there were other Russian geneticists with similar ideas, though for some time their work was known to only a few in the West. His 1937 work Genetics and the Origin of Species

was a key step in bridging the gap between population geneticists and

field naturalists. It presented the conclusions reached by Fisher,

Haldane, and especially Wright in their highly mathematical papers in a

form that was easily accessible to others.

Further, Dobzhansky asserted that evolution was based on material

genes, arranged in a string on physical hereditary structures, the chromosomes, and linked

more or less strongly to each other according to their physical

distances from each other on the chromosomes. As with Haldane and

Fisher, Dobzhansky's "evolutionary genetics" was a genuine science, now unifying cell biology, genetics, and both micro- and macroevolution.

His work emphasized that real world populations had far more genetic

variability than the early population geneticists had assumed in their

models, and that genetically distinct sub-populations were important.

Dobzhansky argued that natural selection worked to maintain genetic

diversity as well as driving change. He was influenced by his exposure

in the 1920s to the work of Sergei Chetverikov,

who had looked at the role of recessive genes in maintaining a

reservoir of genetic variability in a population before his work was

shut down by the rise of Lysenkoism in the Soviet Union.

By 1937, Dobzhansky was able to argue that mutations were the main

source of evolutionary changes and variability, along with chromosome

rearrangements, effects of genes on their neighbours during development,

and polyploidy. Next, genetic drift (he used the term in 1941),

selection, migration, and geographical isolation could change gene

frequencies. Thirdly, mechanisms like ecological or sexual isolation and

hybrid sterility could fix the results of the earlier processes.

Ford's ecological genetics, 1940

E. B. Ford studied polymorphism in the scarlet tiger moth for many years.

E. B. Ford was an experimental naturalist who wanted to test natural selection in nature, virtually inventing the field of ecological genetics.

His work on natural selection in wild populations of butterflies and

moths was the first to show that predictions made by R. A. Fisher were

correct. In 1940, he was the first to describe and define genetic polymorphism, and to predict that human blood group polymorphisms might be maintained in the population by providing some protection against disease. His 1949 book Mendelism and Evolution helped to persuade Dobzhansky to change the emphasis in the third edition of his famous textbook Genetics and the Origin of Species from drift to selection.

Schmalhausen's stabilizing selection, 1941

Ivan Schmalhausen developed the theory of stabilizing selection,

the idea that selection can preserve a trait at some value, publishing a

paper in Russian titled "Stabilizing selection and its place among

factors of evolution" in 1941 and a monograph Factors of Evolution: The Theory of Stabilizing Selection

in 1945. He developed it from J. M. Baldwin's 1902 concept that changes

induced by the environment will ultimately be replaced by hereditary

changes (including the Baldwin effect

on behavior), following that theory's implications to their Darwinian

conclusion, and bringing him into conflict with Lysenkoism. Schmalhausen

observed that stabilizing selection would remove most variations from

the norm, most mutations being harmful. Dobzhansky called the work "an important missing link in the modern view of evolution".

Huxley's popularising synthesis, 1942

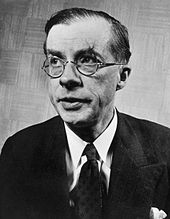

Julian Huxley presented a serious but popularizing version of the theory in his 1942 book Evolution: The Modern Synthesis.

In 1942, Julian Huxley's serious but popularizing Evolution: The Modern Synthesis

introduced a name for the synthesis and intentionally set out to

promote a "synthetic point of view" on the evolutionary process. He

imagined a wide synthesis of many sciences: genetics, developmental

physiology, ecology, systematics, palaeontology, cytology, and

mathematical analysis of biology, and assumed that evolution would

proceed differently in different groups of organisms according to how

their genetic material was organized and their strategies for

reproduction, leading to progressive but varying evolutionary trends. His vision was of an "evolutionary humanism",

with a system of ethics and a meaningful place for "Man" in the world

grounded in a unified theory of evolution which would demonstrate

progress leading to man at its summit. Natural selection was in his view

a "fact of nature capable of verification by observation and

experiment", while the "period of synthesis" of the 1920s and 1930s had

formed a "more unified science", rivaling physics and enabling the "rebirth of Darwinism".

However, the book was not the research text that it appeared to be. In the view of the philosopher of science Michael Ruse, and in Huxley's own opinion, Huxley was "a generalist, a synthesizer of ideas, rather than a specialist".

Ruse observes that Huxley wrote as if he were adding empirical evidence

to the mathematical framework established by Fisher and the population

geneticists, but that this was not so. Huxley avoided mathematics, for

instance not even mentioning Fisher's fundamental theorem of natural selection.

Instead, Huxley used a mass of examples to demonstrate that natural

selection is powerful, and that it works on Mendelian genes. The book

was successful in its goal of persuading readers of the reality of

evolution, effectively illustrating topics such as island biogeography, speciation, and competition. Huxley further showed that the appearance of long-term orthogenetic trends – predictable directions for evolution – in the fossil record were readily explained as allometric growth

(since parts are interconnected). All the same, Huxley did not reject

orthogenesis out of hand, but maintained a belief in progress all his

life, with Homo sapiens as the end point, and he had since 1912 been influenced by the vitalist philosopher Henri Bergson, though in public he maintained an atheistic position on evolution.

Huxley's belief in progress within evolution and evolutionary humanism

was shared in various forms by Dobzhansky, Mayr, Simpson and Stebbins,

all of them writing about "the future of Mankind". Both Huxley and

Dobzhansky admired the palaeontologist priest Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Huxley writing the introduction to Teilhard's 1955 book on orthogenesis, The Phenomenon of Man. This vision required evolution to be seen as the central and guiding principle of biology.

Mayr's allopatric speciation, 1942

Ernst Mayr argued that geographic isolation was needed to provide sufficient reproductive isolation for new species to form.

Ernst Mayr's key contribution to the synthesis was Systematics and the Origin of Species, published in 1942.

It asserted the importance of and set out to explain population

variation in evolutionary processes including speciation. He analyzed in

particular the effects of polytypic species, geographic variation, and isolation by geographic and other means. Mayr emphasized the importance of allopatric speciation, where geographically isolated sub-populations diverge so far that reproductive isolation occurs. He was skeptical of the reality of sympatric speciation

believing that geographical isolation was a prerequisite for building

up intrinsic (reproductive) isolating mechanisms. Mayr also introduced

the biological species concept

that defined a species as a group of interbreeding or potentially

interbreeding populations that were reproductively isolated from all

other populations. Before he left Germany for the United States in 1930, Mayr had been influenced by the work of the German biologist Bernhard Rensch,

who in the 1920s had analyzed the geographic distribution of polytypic

species, paying particular attention to how variations between

populations correlated with factors such as differences in climate.

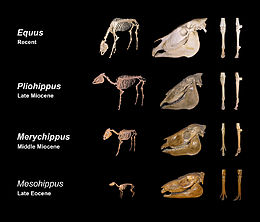

George Gaylord Simpson argued against the naive view that evolution such as of the horse took place in a "straight-line". He noted that any chosen line is one path in a complex branching tree, natural selection having no imposed direction.

Simpson's palaeontology, 1944

George Gaylord Simpson was responsible for showing that the modern synthesis was compatible with palaeontology in his 1944 book Tempo and Mode in Evolution.

Simpson's work was crucial because so many palaeontologists had

disagreed, in some cases vigorously, with the idea that natural

selection was the main mechanism of evolution. It showed that the trends

of linear progression (in for example the evolution of the horse) that earlier palaeontologists had used as support for neo-Lamarckism and orthogenesis did not hold up under careful examination. Instead the fossil record was consistent with the irregular, branching, and non-directional pattern predicted by the modern synthesis.

The Society for the Study of Evolution, 1946

During the war,

Mayr edited a series of bulletins of the Committee on Common Problems

of Genetics, Paleontology, and Systematics, formed in 1943, reporting on

discussions of a "synthetic attack" on the interdisciplinary problems

of evolution. In 1946, the committee became the Society for the Study of

Evolution, with Mayr, Dobzhansky and Sewall Wright the first of the

signatories. Mayr became the editor of its journal, Evolution.

From Mayr and Dobzhansky's point of view, suggests the historian of

science Betty Smocovitis, Darwinism was reborn, evolutionary biology was

legitimized, and genetics and evolution were synthesised into a newly

unified science. Everything fitted in to the new framework, except

"heretics" like Richard Goldschmidt who annoyed Mayr and Dobzhansky by insisting on the possibility of speciation by macromutation, creating "hopeful monsters". The result was "bitter controversy".

Speciation via polyploidy: a diploid cell may fail to separate during meiosis, producing diploid gametes which self-fertilize to produce a fertile tetraploid zygote that cannot interbreed with its parent species.

Stebbins's botany, 1950

The botanist G. Ledyard Stebbins extended the synthesis to encompass botany. He described the important effects on speciation of hybridization and polyploidy in plants in his 1950 book Variation and Evolution in Plants.

These permitted evolution to proceed rapidly at times, polyploidy in

particular evidently being able to create new species effectively

instantaneously.

Definitions by the founders

The

modern synthesis was defined differently by its various founders, with

differing numbers of basic postulates, as shown in the table.

| Component | Mayr 1959 | Stebbins, 1966 | Dobzhansky, 1974 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | (1) Randomness in all events that produce new genotypes, e.g. mutation | (1) a source of variability, but not of direction | (1) yields genetic raw materials |

| Recombination | (1) Randomness in recombination, fertilization | (2) a source of variability, but not of direction |

|

| Chromosomal organisation | (3) affects genetic linkage, arranges variation in gene pool |

| |

| Natural selection | (2) is only direction-giving factor, as seen in adaptations to physical and biotic environment | (4) guides changes to gene pool | (2) constructs evolutionary changes from genetic raw materials |

| Reproductive isolation | (5) limits direction in which selection can guide the population | (3) makes divergence irreversible in sexual organisms |

After the synthesis

After the synthesis, evolutionary biology continued to develop with major contributions from workers including W. D. Hamilton, George C. Williams, E. O. Wilson, Edward B. Lewis and others.

Hamilton's inclusive fitness, 1964

In 1964, W. D. Hamilton published two papers on "The Genetical Evolution of Social Behaviour". These defined inclusive fitness

as the number of offspring equivalents an individual rears, rescues or

otherwise supports through its behavior. This was contrasted with

personal reproductive fitness, the number of offspring that the

individual directly begets. Hamilton, and others such as John Maynard Smith,

argued that a gene's success consisted in maximizing the number of

copies of itself, either by begetting them or by indirectly encouraging

begetting by related individuals who shared the gene, the theory of kin selection.

Williams's gene-centred evolution, 1966

In 1966, George C. Williams published Adaptation and Natural Selection, outlined a gene-centred view of evolution following Hamilton's concepts, disputing the idea of evolutionary progress, and attacking the then widespread theory of group selection. Williams argued that natural selection worked by changing the frequency of alleles, and could not work at the level of groups. Gene-centered evolution was popularized by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene and developed in his more technical writings.

Wilson's sociobiology, 1975

Ant societies have evolved elaborate caste structures, widely different in size and function.

In 1975, E. O. Wilson published his controversial book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis, the subtitle alluding to the modern synthesis

as he attempted to bring the study of animal society into the

evolutionary fold. This appeared radically new, although Wilson was

following Darwin, Fisher, Dawkins and others. Critics such as Gerhard Lenski

noted that he was following Huxley, Simpson and Dobzhansky's approach,

which Lenski considered needlessly reductive as far as human society was

concerned. By 2000, the proposed discipline of sociobiology had morphed into the relatively well-accepted discipline of evolutionary psychology.

Lewis's homeotic genes, 1978

Evolutionary developmental biology has formed a synthesis of evolutionary and developmental biology, discovering deep homology between the embryogenesis of such different animals as insects and vertebrates.

In 1977, recombinant DNA technology enabled biologists to start to explore the genetic control of development. The growth of evolutionary developmental biology from 1978, when Edward B. Lewis discovered homeotic genes, showed that many so-called toolkit genes

act to regulate development, influencing the expression of other genes.

It also revealed that some of the regulatory genes are extremely

ancient, so that animals as different as insects and mammals share

control mechanisms; for example, the Pax6 gene is involved in forming the eyes of mice and of fruit flies. Such deep homology provided strong evidence for evolution and indicated the paths that evolution had taken.

Later syntheses

In 1982, a historical note on a series of evolutionary biology books

could state without qualification that evolution is the central

organizing principle of biology. Smocovitis commented on this that "What

the architects of the synthesis had worked to construct had by 1982

become a matter of fact", adding in a footnote that "the centrality of

evolution had thus been rendered tacit knowledge, part of the received wisdom of the profession".

By the late 20th century, however, the modern synthesis was

showing its age, and fresh syntheses to remedy its defects and fill in

its gaps were proposed from different directions. These have included

such diverse fields as the study of society, developmental biology, epigenetics, molecular biology, microbiology, genomics, symbiogenesis, and horizontal gene transfer. The physiologist Denis Noble

argues that these additions render neo-Darwinism in the sense of the

early 20th century's modern synthesis "at the least, incomplete as a

theory of evolution", and one that has been falsified by later biological research.

Michael Rose and Todd Oakley note that evolutionary biology, formerly divided and "Balkanized",

has been brought together by genomics. It has in their view discarded

at least five common assumptions from the modern synthesis, namely that

the genome is always a well-organized set of genes; that each gene has a

single function; that species are well adapted biochemically to their

ecological niches; that species are the durable units of evolution, and

all levels from organism to organ, cell and molecule within the species

are characteristic of it; and that the design of every organism and

cell is efficient. They argue that the "new biology" integrates

genomics, bioinformatics, and evolutionary genetics into a general-purpose toolkit for a "Postmodern Synthesis".

Pigliucci's extended evolutionary synthesis, 2007

In 2007, more than half a century after the modern synthesis, Massimo Pigliucci called for an extended evolutionary synthesis to incorporate aspects of biology that had not been included or had not existed in the mid-20th century.

It revisits the relative importance of different factors, challenges

assumptions made in the modern synthesis, and adds new factors such as multilevel selection, transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, niche construction, and evolvability.

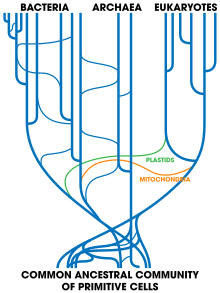

Koonin's 'post-modern' evolutionary synthesis, 2009

A 21st century tree of life showing horizontal gene transfers among prokaryotes and the saltational endosymbiosis events that created the eukaryotes, neither fitting into the 20th century's modern synthesis

In 2009, Darwin's 200th anniversary, the Origin of Species' 150th, and the 200th of Lamarck's "early evolutionary synthesis", Philosophie Zoologique, the evolutionary biologist Eugene Koonin stated that while "the edifice of the [early 20th century] Modern Synthesis has crumbled, apparently, beyond repair",

a new 21st century synthesis could be glimpsed. Three interlocking

revolutions had, he argued, taken place in evolutionary biology:

molecular, microbiological, and genomic. The molecular revolution

included the neutral theory, that most mutations are neutral and that

purifying selection happens more often than the positive form, and that

all current life evolved from a single common ancestor. In microbiology, the synthesis has expanded to cover the prokaryotes, using ribosomal RNA to form a tree of life. Finally, genomics

brought together the molecular and microbiological syntheses, noting

that a molecular view shows that the tree of life is problematic. In

particular, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria means that prokaryotes freely share genes, challenging Mayr's foundational definition of species. Further, horizontal gene transfer, gene duplication, and "momentous events" like endosymbiosis

enable evolution to proceed in sudden jumps, ending the old

gradualist-saltationist debate by showing that on this point Darwin's

gradualism was wrong. The idea of progress in biology, too, is seen to be wrong, along with the modern synthesis belief in pan-adaptationism, that everything is optimally adapted: genomes plainly are not. Many of these points had already been made by other researchers such as Ulrich Kutschera and Karl J. Niklas.

Towards a replacement synthesis

Inputs

to the modern synthesis, with other topics (inverted colours) such as

developmental biology that were not joined with evolutionary biology

until the turn of the 21st century

Biologists, alongside scholars of the history and philosophy of

biology, have continued to debate the need for, and possible nature of, a

replacement synthesis. For example, in 2017 Philippe Huneman and Denis

M. Walsh stated in their book Challenging the Modern Synthesis

that numerous theorists had pointed out that the disciplines of

embryological developmental theory, morphology, and ecology had been

omitted. They noted that all such arguments amounted to a continuing

desire to replace the modern synthesis with one that united "all

biological fields of research related to evolution, adaptation, and

diversity in a single theoretical frame."

They observed further that there are two groups of challenges to the

way the modern synthesis viewed inheritance. The first is that other

modes such as epigenetic inheritance, phenotypic plasticity, the Baldwin effect, and the maternal effect

allow new characteristics to arise and be passed on, and for the genes

to catch up with the new adaptations later. The second is that all such

mechanisms are part, not of an inheritance system, but a developmental system:

the fundamental unit is not a discrete selfishly competing gene, but a

collaborating system that works at all levels from genes and cells to

organisms and cultures to guide evolution.

Historiography

Looking back at the conflicting accounts of the modern synthesis, the historian Betty Smocovitis notes in her 1996 book Unifying Biology: The Evolutionary Synthesis and Evolutionary Biology

that both historians and philosophers of biology have attempted to

grasp its scientific meaning, but have found it "a moving target"; the only thing they agreed on was that it was a historical event.

In her words "by the late 1980s the notoriety of the evolutionary

synthesis was recognized . . . So notorious did 'the synthesis' become,

that few serious historically minded analysts would touch the subject,

let alone know where to begin to sort through the interpretive mess left

behind by the numerous critics and commentators".