Artist's conception of MER rovers on Mars

NASA's Mars Exploration Rover (MER) mission was a robotic space mission involving two Mars rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, exploring the planet Mars. It began in 2003 with the launch of the two rovers: MER-A Spirit and MER-B Opportunity—to explore the Martian surface and geology; both landed on Mars at separate locations in January 2004. Both rovers far outlived their planned missions of 90 Martian solar days: MER-A Spirit was active until March 22, 2010, while MER-B Opportunity was active until June 10, 2018 and holds the record for the longest distance driven by any off-Earth wheeled vehicle.

Objectives

The mission's scientific objective was to search for and characterize a wide range of rocks and soils that hold clues to past water activity on Mars. The mission is part of NASA's Mars Exploration Program, which includes three previous successful landers: the two Viking program landers in 1976 and Mars Pathfinder probe in 1997.

The total cost of building, launching, landing and operating the rovers on the surface for the initial 90-sol primary mission was US$820 million.

Since the rovers have continued to function beyond their initial 90 sol

primary mission, they have each received five mission extensions. The

fifth mission extension was granted in October 2007, and ran to the end

of 2009.

The total cost of the first four mission extensions was $104 million,

and the fifth mission extension is expected to cost at least

$20 million.

In July 2007, during the fourth mission extension, Martian dust

storms blocked sunlight to the rovers and threatened the ability of the

craft to gather energy through their solar panels,

causing engineers to fear that one or both of them might be permanently

disabled. However, the dust storms lifted, allowing them to resume

operations.

On May 1, 2009, during its fifth mission extension, Spirit became stuck in soft soil on Mars.

After nearly nine months of attempts to get the rover back on track,

including using test rovers on Earth, NASA announced on January 26, 2010

that Spirit was being retasked as a stationary science platform. This mode would enable Spirit to assist scientists in ways that a mobile platform could not, such as detecting "wobbles" in the planet's rotation that would indicate a liquid core.

Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) lost contact with Spirit after last

hearing from the rover on March 22, 2010 and continued attempts to

regain communications lasted until May 25, 2011, bringing the elapsed

mission time to 6 years 2 months 19 days, or over 25 times the original

planned mission duration.

In recognition of the vast amount of scientific information amassed by both rovers, two asteroids have been named in their honor: 37452 Spirit and 39382 Opportunity. The mission is managed for NASA by the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which designed, built, and is operating the rovers.

On January 24, 2014, NASA reported that current studies by the remaining rover Opportunity as well as by the newer Mars Science Laboratory rover Curiosity will now be searching for evidence of ancient life, including a biosphere based on autotrophic, chemotrophic and/or chemolithoautotrophic microorganisms, as well as ancient water, including fluvio-lacustrine environments (plains related to ancient rivers or lakes) that may have been habitable. The search for evidence of habitability, taphonomy (related to fossils), and organic carbon on the planet Mars is now a primary NASA objective.

The scientific objectives of the Mars Exploration Rover mission are to:

- Search for and characterize a variety of rocks and soils that hold clues to past water activity. In particular, samples sought include those that have minerals deposited by water-related processes such as precipitation, evaporation, sedimentary cementation, or hydrothermal activity.

- Determine the distribution and composition of minerals, rocks, and soils surrounding the landing sites.

- Determine what geologic processes have shaped the local terrain and influenced the chemistry. Such processes could include water or wind erosion, sedimentation, hydrothermal mechanisms, volcanism, and cratering.

- Perform calibration and validation of surface observations made by Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter instruments. This will help determine the accuracy and effectiveness of various instruments that survey Martian geology from orbit.

- Search for iron-containing minerals, and to identify and quantify relative amounts of specific mineral types that contain water or were formed in water, such as iron-bearing carbonates.

- Characterize the mineralogy and textures of rocks and soils to determine the processes that created them.

- Search for geological clues to the environmental conditions that existed when liquid water was present.

- Assess whether those environments were conducive to life.

History

The MER-A and MER-B probes were launched on June 10, 2003 and July 7, 2003, respectively. Though both probes launched on Boeing Delta II 7925-9.5 rockets from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Space Launch Complex 17 (CCAFS SLC-17), MER-B was on the heavy version of that launch vehicle, needing the extra energy for Trans-Mars injection. The launch vehicles were integrated onto pads right next to each other,

with MER-A on CCAFS SLC-17A and MER-B on CCAFS SLC-17B. The dual pads

allowed for working the 15- and 21-day planetary launch periods close

together; the last possible launch day for MER-A was June 19, 2003 and

the first day for MER-B was June 25, 2003. NASA's Launch Services Program managed the launch of both spacecraft.

The probes landed in January 2004 in widely separated equatorial locations on Mars.

Timeline of the Mars Exploration mission

On January 21, 2004, the Deep Space Network lost contact with Spirit, for reasons originally thought to be related to a thunderstorm over Australia. The rover transmitted a message with no data, but later that day missed another communications session with the Mars Global Surveyor. The next day, JPL

received a beep from the rover, indicating that it was in fault mode.

On January 23, the flight team succeeded in making the rover send. The

fault was believed to have been caused by an error in the rover's flash memory

subsystem. The rover did not perform any scientific activities for ten

days, while engineers updated its software and ran tests. The problem

was corrected by reformatting Spirit's flash memory and using a software patch to avoid memory overload; Opportunity was also upgraded with the patch as a precaution. Spirit returned to full scientific operations by February 5.

On March 23, 2004, a news conference was held announcing "major

discoveries" of evidence of past liquid water on the Martian surface. A

delegation of scientists showed pictures and data revealing a stratified

pattern and cross bedding in the rocks of the outcrop inside a crater in Meridiani Planum, landing site of MER-B, Opportunity. This suggested that water once flowed in the region. The irregular distribution of chlorine and bromine also suggests that the place was once the shoreline of a salty sea, now evaporated.

On April 8, 2004, NASA announced that it was extending the

mission life of the rovers from three to eight months. It immediately

provided additional funding of US $15 million through September, and

$2.8 million per month for continuing operations. Later that month, Opportunity arrived at Endurance crater,

taking about five days to drive the 200 meters. NASA announced on

September 22 that it was extending the mission life of the rovers for

another six months. Opportunity was to leave Endurance crater, visit its discarded heat shield, and proceed to Victoria crater. Spirit was to attempt to climb to the top of the Columbia Hills.

With the two rovers still functioning well, NASA later announced another 18-month extension of the mission to September 2006. Opportunity was to visit the "Etched Terrain" and Spirit was to climb a rocky slope toward the top of Husband Hill. On August 21, 2005, Spirit reached the summit of Husband Hill after 581 sols and a journey of 4.81 kilometers (2.99 mi).

Spirit celebrated its one Martian year anniversary (669 sols or 687 Earth days) on November 20, 2005. Opportunity

celebrated its anniversary on December 12, 2005. At the beginning of

the mission, it was expected that the rovers would not survive much

longer than 90 Martian days. The Columbia Hills were "just a dream",

according to rover driver Chris Leger. Spirit explored the semicircular rock formation known as Home Plate. It is a layered rock outcrop that puzzles and excites scientists.

It is thought that its rocks are explosive volcanic deposits, though

other possibilities exist, including impact deposits or sediment borne

by wind or water.

Spirit's front right wheel ceased working on March 13, 2006, while the rover was moving itself to McCool Hill.

Its drivers attempted to drag the dead wheel behind Spirit, but this

only worked until reaching an impassable sandy area on the lower slopes.

Drivers directed Spirit to a smaller sloped feature, dubbed "Low

Ridge Haven", where it spent the long Martian winter, waiting for

spring and increased solar power levels suitable for driving. That

September, Opportunity reached the rim of Victoria crater, and Spaceflight Now reported that NASA had extended mission for the two rovers through September 2007. On February 6, 2007, Opportunity became the first spacecraft to traverse ten kilometers (6.2 miles) on the surface of Mars.

Opportunity was poised to enter Victoria Crater from its perch on the rim of Duck Bay on June 28, 2007, but due to extensive dust storms, it was delayed until the dust had cleared and power returned to safe levels. Two months later, Spirit and Opportunity

resumed driving after hunkering down during raging dust storms that

limited solar power to a level that nearly caused the permanent failure

of both rovers.

On October 1, 2007, both Spirit and Opportunity entered their fifth mission extension that extended operations into 2009, allowing the rovers to have spent five years exploring the Martian surface, pending their continued survival.

On August 26, 2008, Opportunity began its three-day climb out of Victoria crater amidst concerns that power spikes, similar to those seen on Spirit

before the failure of its right-front wheel, might prevent it from ever

being able to leave the crater if a wheel failed. Project scientist

Bruce Banerdt also said, "We've done everything we entered Victoria

Crater to do and more." Opportunity will return to the plains in

order to characterize Meridiani Planum's vast diversity of rocks—some

of which may have been blasted out of craters such as Victoria. The

rover had been exploring Victoria Crater since September 11, 2007. As of January 2009, the two rovers had collectively sent back 250,000 images and traveled over 21 kilometers (13 mi).

After driving about 3.2 kilometers (2.0 mi) since it left Victoria crater, Opportunity first saw the rim of Endeavor crater on March 7, 2009. It passed the 16 km (9.9 mi) mark along the way on sol 1897. Meanwhile, at Gusev crater, Spirit was dug in deep into the Martian sand, much as Opportunity was at Purgatory Dune in 2005.

On January 3 and 24, 2010, Spirit and Opportunity marked six years on Mars, respectively. On January 26, NASA announced that Spirit will be used as a stationary research platform after several months of unsuccessful attempts to free the rover from soft sand.

NASA announced on March 24, 2010, that Opportunity, which

has an estimated remaining drive distance of 12 km to Endeavor Crater,

has traveled over 20 km since the start of its mission. Each rover was designed with a mission driving distance goal of just 600 meters. One week later, they announced that Spirit may have gone into hibernation for the Martian winter and might not wake up again for months.

On September 8, 2010, it was announced that Opportunity had reached the halfway point of the 19-kilometer journey between Victoria crater and Endeavor crater.

On May 22, 2011, NASA announced that it will cease attempts to contact Spirit,

which has been stuck in a sand trap for two years. The last successful

communication with the rover was on March 22, 2010. The final

transmission to the rover was on May 25, 2011.

In April 2013, a photo sent back by one of the rovers became widely circulated on social networking and news sites such as Reddit that appeared to depict a human penis carved into the Martian dirt.

On May 16, 2013, NASA announced that Opportunity had driven further than any other NASA vehicle on a world other than Earth. After Opportunity's total odometry went over 35.744 km (22.210 mi), the rover surpassed the total distance driven by the Apollo 17 Lunar Roving Vehicle.

On July 28, 2014, NASA announced that Opportunity had driven further than any other vehicle on a world other than Earth. Opportunity covered over 40 km (25 mi), surpassing the total distance of 39 km (24 mi) driven by the Lunokhod 2 lunar rover, the previous record-holder.

On March 23, 2015, NASA announced that Opportunity had driven the full 42.2 km (26.2 mi) distance of a marathon, with a finish time of roughly 11 years, 2 months.

On June 2018, Opportunity was caught in a global-scale

dust storm and the rover's solar panels were not able to generate enough

power, with the last contact on June 10, 2018. NASA resumed sending

commands after the dust storm subsided but the rover remained silent,

possibly due to a catastrophic failure or a layer of dust covered its

solar panels.

A press conference was held on February 13, 2019, that after numerous attempts to obtain contact with Opportunity with no response since June 2018, NASA declared

Opportunity mission over, which also draws the 16-year long Mars Exploration Rover mission to a close.

Spacecraft design

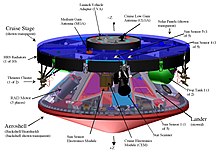

MER launch configuration, break apart illustration

The Mars Exploration Rover was designed to be stowed atop a Delta II rocket. Each spacecraft consists of several components:

- Rover: 185 kg (408 lb)

- Lander: 348 kg (767 lb)

- Backshell / Parachute: 209 kg (461 lb)

- Heat Shield: 78 kg (172 lb)

- Cruise Stage: 193 kg (425 lb)

- Propellant: 50 kg (110 lb)

- Instruments: 5 kg (11 lb)

Total mass is 1,063 kg (2,344 lb).

Cruise stage

Cruise stage of Opportunity rover

MER cruise stage diagram

The cruise stage is the component of the spacecraft that is used for

travel from Earth to Mars. It is very similar to the Mars Pathfinder in

design and is approximately 2.65 meters (8.7 ft) in diameter and 1.6 m (5.2 ft) tall, including the entry vehicle (see below).

The primary structure is aluminum with an outer ring of ribs covered by the solar panels, which are about 2.65 m (8.7 ft) in diameter. Divided into five sections, the solar arrays can provide up to 600 watts of power near Earth and 300 W at Mars.

Heaters and multi-layer insulation keep the electronics "warm". A freon

system removes heat from the flight computer and communications

hardware inside the rover so they do not overheat. Cruise avionics

systems allow the flight computer to interface with other electronics,

such as the sun sensors, star scanner and heaters.

The star scanner (without a backup system) and sun sensor

allowed the spacecraft to know its orientation in space by analyzing

the position of the Sun and other stars in relation to itself. Sometimes

the craft could be slightly off course; this was expected, given the

500-million-kilometer (320 million mile) journey. Thus navigators

planned up to six trajectory correction maneuvers, along with health

checks.

To ensure the spacecraft arrived at Mars in the right place for

its landing, two light-weight, aluminum-lined tanks carried about 31 kg

(about 68 lb) of hydrazine propellant.

Along with cruise guidance and control systems, the propellant allowed

navigators to keep the spacecraft on course. Burns and pulse firings of

the propellant allowed three types of maneuvers:

- An axial burn uses pairs of thrusters to change spacecraft velocity;

- A lateral burn uses two "thruster clusters" (four thrusters per cluster) to move the spacecraft "sideways" through seconds-long pulses;

- Pulse mode firing uses coupled thruster pairs for spacecraft precession maneuvers (turns).

Communication

The spacecraft used a high-frequency X band radio wavelength to communicate, which allowed for less power and smaller antennas than many older craft, which used S band.

Navigators sent commands through two antennas on the cruise stage: a cruise low-gain antenna

mounted inside the inner ring, and a cruise medium-gain antenna in the

outer ring. The low-gain antenna was used close to Earth. It is

omni-directional, so the transmission power that reached Earth fell

faster with increasing distance. As the craft moved closer to Mars, the

Sun and Earth moved closer in the sky as viewed from the craft, so less

energy reached Earth. The spacecraft then switched to the medium-gain

antenna, which directed the same amount of transmission power into a

tighter beam toward Earth.

During flight, the spacecraft was spin-stabilized with a spin rate of two revolutions per minute (rpm). Periodic updates kept antennas pointed toward Earth and solar panels toward the Sun.

Aeroshell

Overview of the Mars Exploration Rover aeroshell

The aeroshell maintained a protective covering for the lander during

the seven-month voyage to Mars. Together with the lander and the rover,

it constituted the "entry vehicle". Its main purpose was to protect the

lander and the rover inside it from the intense heat of entry into the

thin Martian atmosphere. It was based on the Mars Pathfinder and Mars

Viking designs.

Parts

The aeroshell was made of two main parts: a heat shield

and a backshell. The heat shield was flat and brownish, and protected

the lander and rover during entry into the Martian atmosphere and acted

as the first aerobrake for the spacecraft. The backshell was large, cone-shaped and painted white. It carried the parachute and several components used in later stages of entry, descent, and landing, including:

- A parachute (stowed at the bottom of the backshell);

- The backshell electronics and batteries that fire off pyrotechnic devices like separation nuts, rockets and the parachute mortar;

- A Litton LN-200 Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), which monitors and reports the orientation of the backshell as it swings under the parachute;

- Three large solid rocket motors called RAD rockets (Rocket Assisted Descent), each providing about a ton of force (10 kilonewtons) for about 60 seconds;

- Three small solid rockets called TIRS (mounted so that they aim horizontally out the sides of the backshell) that provide a small horizontal kick to the backshell to help orient the backshell more vertically during the main RAD rocket burn.

Composition

Built by the Lockheed Martin Astronautics Co. in Denver, Colorado, the aeroshell is made of an aluminium honeycomb structure sandwiched between graphite-epoxy face sheets. The outside of the aeroshell is covered with a layer of phenolic honeycomb. This honeycomb is filled with an ablative material (also called an "ablator"), that dissipates heat generated by atmospheric friction.

The ablator itself is a unique blend of cork wood, binder and many tiny silica

glass spheres. It was invented for the heat shields flown on the Viking

Mars lander missions. A similar technology was used in the first US manned space missions Mercury, Gemini and Apollo. It was specially formulated to react chemically with the Martian atmosphere during entry

and carry heat away, leaving a hot wake of gas behind the vehicle. The

vehicle slowed from 19,000 to 1,600 km/h (5,300 to 440 m/s) in about a

minute, producing about 60 m/s2 (6 g) of acceleration on the lander and rover.

The backshell and heat shield are made of the same materials, but the heat shield has a thicker, 13 mm (1⁄2 in), layer of the ablator. Instead of being painted, the backshell was covered with a very thin aluminized PET film blanket to protect it from the cold of deep space. The blanket vaporized during entry into the Martian atmosphere.

Parachute

Mars Exploration Rover's parachute test

The parachute helped slow the spacecraft during entry, descent, and landing. It is located in the backshell.

Design

The 2003

parachute design was part of a long-term Mars parachute technology

development effort and is based on the designs and experience of the

Viking and Pathfinder missions. The parachute for this mission is 40%

larger than Pathfinder's because the largest load for the Mars

Exploration Rover is 80 to 85 kilonewtons

(kN) or 80 to 85 kN (18,000 to 19,000 lbf) when the parachute fully

inflates. By comparison, Pathfinder's inflation loads were approximately

35 kN (about 8,000 lbf). The parachute was designed and constructed in South Windsor, Connecticut by Pioneer Aerospace, the company that also designed the parachute for the Stardust mission.

Composition

The parachute is made of two durable, lightweight fabrics: polyester and nylon. A triple bridle made of Kevlar connects the parachute to the backshell.

The amount of space available on the spacecraft for the parachute

is so small that the parachute had to be pressure-packed. Before

launch, a team tightly folded the 48 suspension lines, three bridle

lines, and the parachute. The parachute team loaded the parachute in a

special structure that then applied a heavy weight to the parachute

package several times. Before placing the parachute into the backshell,

the parachute was heat set to sterilize it.

Connected systems

Descent is halted by retrorockets and lander is dropped 10 m (33 ft) to the surface in this computer generated impression.

Zylon Bridles: After the parachute was deployed at an altitude

of about 10 km (6.2 mi) above the surface, the heatshield was released

using 6 separation nuts and push-off springs. The lander then separated

from the backshell and "rappelled" down a metal tape on a centrifugal braking system

built into one of the lander petals. The slow descent down the metal

tape placed the lander in position at the end of another bridle

(tether), made of a nearly 20 m (66 ft) long braided Zylon.

Zylon is an advanced fiber material, similar to Kevlar, that is

sewn in a webbing pattern (like shoelace material) to make it stronger.

The Zylon bridle provides space for airbag deployment, distance from the

solid rocket motor exhaust stream, and increased stability. The bridle

incorporates an electrical harness that allows the firing of the solid

rockets from the backshell as well as provides data from the backshell

inertial measurement unit (which measures rate and tilt of the

spacecraft) to the flight computer in the rover.

Rocket assisted descent (RAD) motors: Because the

atmospheric density of Mars is less than 1% of Earth's, the parachute

alone could not slow down the Mars Exploration Rover enough to ensure a

safe, low landing speed. The spacecraft descent was assisted by rockets

that brought the spacecraft to a dead stop 10–15 m (33–49 ft) above the

Martian surface.

Radar altimeter unit: A radar altimeter

unit was used to determine the distance to the Martian surface. The

radar's antenna is mounted at one of the lower corners of the lander

tetrahedron. When the radar measurement showed the lander was the

correct distance above the surface, the Zylon bridle was cut, releasing

the lander from the parachute and backshell so that it was free and

clear for landing. The radar data also enabled the timing sequence on

airbag inflation and backshell RAD rocket firing.

Airbags

Artist's concept of inflated airbags

Airbags

used in the Mars Exploration Rover mission are the same type that Mars

Pathfinder used in 1997. They had to be strong enough to cushion the

spacecraft if it landed on rocks or rough terrain and allow it to bounce

across Mars' surface at highway speeds (about 100 km/h) after landing.

The airbags had to be inflated seconds before touchdown and deflated

once safely on the ground.

The airbags were made of Vectran,

like those on Pathfinder. Vectran has almost twice the strength of

other synthetic materials, such as Kevlar, and performs better in cold

temperatures. Six 100 denier

(10 mg/m) layers of Vectran protected one or two inner bladders of

Vectran in 200 denier (20 mg/m). Using 100 denier (10 mg/m) leaves more

fabric in the outer layers where it is needed, because there are more

threads in the weave.

Each rover used four airbags with six lobes each, all of which

were connected. Connection was important, since it helped abate some of

the landing forces by keeping the bag system flexible and responsive to

ground pressure. The airbags were not attached directly to the rover,

but were held to it by ropes crisscrossing the bag structure. The ropes

gave the bags shape, making inflation easier. While in flight, the bags

were stowed along with three gas generators that are used for inflation.

Lander

MER lander petals opening (Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The spacecraft lander is a protective shell that houses the rover,

and together with the airbags, protects it from the forces of impact.

The lander is a tetrahedron shape, whose sides open like petals. It is strong and light, and made of beams and sheets. The beams consist of layers of graphite

fiber woven into a fabric that is lighter than aluminium and more rigid

than steel. Titanium fittings are glued and fitted onto the beams to

allow it to be bolted together. The rover was held inside the lander by bolts and special nuts that were released after landing with small explosives.

Uprighting

After

the lander stopped bouncing and rolling on the ground, it came to rest

on the base of the tetrahedron or one of its sides. The sides then

opened to make the base horizontal and the rover upright. The sides are

connected to the base by hinges, each of which has a motor strong enough

to lift the lander. The rover plus lander has a mass of about 533 kilograms (1,175 pounds).

The rover alone has a mass of about 185 kg (408 lb). The gravity on

Mars is about 38% of Earth's, so the motor does not need to be as

powerful as it would on Earth.

The rover contains accelerometers

to detect which way is down (toward the surface of Mars) by measuring

the pull of gravity. The rover computer then commanded the correct

lander petal to open to place the rover upright. Once the base petal was

down and the rover was upright, the other two petals were opened.

The petals initially opened to an equally flat position, so all

sides of the lander were straight and level. The petal motors are strong

enough so that if two of the petals come to rest on rocks, the base

with the rover would be held in place like a bridge above the ground.

The base will hold at a level even with the height of the petals resting

on rocks, making a straight flat surface throughout the length of the

open, flattened lander. The flight team on Earth could then send

commands to the rover to adjust the petals and create a safe path for

the rover to drive off the lander and onto the Martian surface without

dropping off a steep rock.

Moving the payload onto Mars

Spirit's lander on Mars

The moving of the rover off the lander is called the egress phase of

the mission. The rover must avoid having its wheels caught in the airbag

material or falling off a sharp incline. To help this, a retraction

system on the petals slowly drags the airbags toward the lander before

the petals open. Small ramps on the petals fan out to fill spaces

between the petals. They cover uneven terrain, rock obstacles, and

airbag material, and form a circular area from which the rover can drive

off in more directions. They also lower the step that the rover must

climb down. They are nicknamed "batwings", and are made of Vectran

cloth.

About three hours were allotted to retract the airbags and deploy the lander petals.

Rover design

Mars Exploration Rover (rear) vs. Sojourner rover (Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech)

Interactive 3D model of the MER

The rovers are six-wheeled, solar-powered robots that stand 1.5 m

(4.9 ft) high, 2.3 m (7.5 ft) wide and 1.6 m (5.2 ft) long. They weigh

180 kg (400 lb), 35 kg (77 lb) of which is the wheel and suspension

system.

Drive system

Drive wheel from the Mars Exploration Rovers, with integral suspension flexures.

Each rover has six wheels mounted on a rocker-bogie

suspension system that ensures wheels remain on the ground while

driving over rough terrain. The design reduces the range of motion of

the rover body by half, and allows the rover to go over obstacles or

through holes that are more than a wheel diameter (250 millimeters

(9.8 in)) in size. The rover wheels are designed with integral compliant

flexures which provide shock absorption during movement. Additionally, the wheels have cleats which provide grip for climbing in soft sand and scrambling over rocks.

Each wheel has its own drive motor. The two front and two rear

wheels each have individual steering motors. This allows the vehicle to

turn in place, a full revolution, and to swerve and curve, making

arching turns. The motors for the rovers have been designed by the Swiss

company Maxon Motor.

The rover is designed to withstand a tilt of 45 degrees in any

direction without overturning. However, the rover is programmed through

its "fault protection limits" in its hazard avoidance software to avoid

exceeding tilts of 30 degrees.

Each rover can spin one of its front wheels in place to grind

deep into the terrain. It is to remain motionless while the digging

wheel is spinning. The rovers have a top speed on flat hard ground of

50 mm/s (2 in/s). The average speed is 10 mm/s, because its hazard

avoidance software causes it to stop every 10 seconds for 20 seconds to

observe and understand the terrain into which it has driven.

Power and electronic systems

Circular projection showing MER-A Spirit's solar panels covered in dust in October 2007 on Mars. Unexpected cleaning events have periodically increased power.

When fully illuminated, the rover triplejunction solar arrays generate about 140 watts for up to four hours per Martian day (sol). The rover needs about 100 watts to drive. Its power system includes two rechargeable lithium ion

batteries weighing 7.15 kg (15.8 lb) each, that provide energy when the

sun is not shining, especially at night. Over time, the batteries will

degrade and will not be able to recharge to full capacity.

For comparison, the Mars Science Laboratory's power system is composed of a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG) produced by Boeing.

The MMRTG is designed to provide 125W of electrical power at the start

of the mission, falling to 100W after 14 years of service.

It is used to power the MSL's many systems and instruments. Solar

panels were also considered for the MSL, but RTGs provide constant

power, regardless of the time of day, and thus the versatility to work

in dark environments and high latitudes where solar energy is not

readily available. The MSL generates 2.5 kilowatt hours per day, compared to the Mars Exploration Rovers, which can generate about 0.6 kilowatt hours per day.

It was thought that by the end of the 90-sol mission, the

capability of the solar arrays to generate power would likely be reduced

to about 50 watts. This was due to anticipated dust coverage on the

solar arrays, and the change in season. Over three Earth years later,

however, the rovers' power supplies hovered between 300 watt-hours

and 900 watt-hours per day, depending on dust coverage. Cleaning events

(dust removal by wind) have occurred more often than NASA expected,

keeping the arrays relatively free of dust and extending the life of the

mission. During a 2007 global dust storm on Mars, both rovers

experienced some of the lowest power of the mission; Opportunity dipped to 128 watt-hours. In November 2008, Spirit had overtaken this low-energy record with a production of 89 watt-hours, due to dust storms in the region of Gusev crater.

The rovers run a VxWorks embedded operating system on a radiation-hardened 20 MHz RAD6000 CPU with 128 MB of DRAM with error detection and correction and 3 MB of EEPROM. Each rover also has 256 MB of flash memory.

To survive during the various mission phases, the rover's vital

instruments must stay within a temperature of −40 °C to +40 °C (−40 °F

to 104 °F). At night, the rovers are heated by eight radioisotope heater units (RHU), which each continuously generate 1 W of thermal energy from the decay of radioisotopes, along with electrical heaters that operate only when necessary. A sputtered gold film and a layer of silica aerogel are used for insulation.

Communication

Pancam Mast Assembly (PMA)

Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT)

Alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS) (Courtesy NASA/JPL-Caltech)

The rover has an X band low-gain and an X band high-gain antenna for communications to and from the Earth, as well as an ultra high frequency monopole antenna for relay communications. The low-gain antenna is omnidirectional, and transmits data at a low rate to Deep Space Network

(DSN) antennas on Earth. The high-gain antenna is directional and

steerable, and can transmit data to Earth at a higher rate. The rovers

use the UHF monopole and its CE505 radio to communicate with spacecraft

orbiting Mars, the Mars Odyssey and (before its failure) the Mars Global Surveyor (already more than 7.6 terabits of data were transferred using its Mars Relay antenna and Mars Orbiter Camera's memory buffer of 12 MB). Since MRO

went into orbit around Mars, the landers have also used it as a relay

asset. Most of the lander data is relayed to Earth through Odyssey and

MRO. The orbiters can receive rover signals at a much higher data rate

than the Deep Space Network can, due to the much shorter distances from

rover to orbiter. The orbiters then quickly relay the rover data to the

Earth using their large and high-powered antennas.

Each rover has nine cameras, which produce 1024-pixel by 1024-pixel images at 12 bits per pixel,

but most navigation camera images and image thumbnails are truncated to

8 bits per pixel to conserve memory and transmission time. All images

are then compressed using ICER

before being stored and sent to Earth. Navigation, thumbnail, and many

other image types are compressed to approximately 0.8 to 1.1 bits/pixel.

Lower bit rates (less than 0.5-bit/pixel) are used for certain

wavelengths of multi-color panoramic images.

ICER is based on wavelets,

and was designed specifically for deep-space applications. It produces

progressive compression, both lossless and lossy, and incorporates an

error-containment scheme to limit the effects of data loss on the

deep-space channel. It outperforms the lossy JPEG image compressor and

the lossless Rice compressor used by the Mars Pathfinder mission.

Scientific instrumentation

The rover has various instruments. Three are mounted on the Pancam Mast Assembly (PMA):

- Panoramic Cameras (Pancam), two cameras with color filter wheels for determining the texture, color, mineralogy, and structure of the local terrain.

- Navigation Cameras (Navcam), two cameras that have larger fields of view but lower resolution and are monochromatic, for navigation and driving.

- A periscope assembly for the Miniature Thermal Emission Spectrometer (Mini-TES), which identifies promising rocks and soils for closer examination, and determines the processes that formed them. The Mini-TES was built by Arizona State University. The periscope assembly features two beryllium fold mirrors, a shroud that closes to minimize dust contamination in the assembly, and stray-light rejection baffles that are strategically placed within the graphite epoxy tubes.

The cameras are mounted 1.5 meters high on the Pancam Mast Assembly.

The PMA is deployed via the Mast Deployment Drive (MDD). The Azimuth

Drive, mounted directly above the MDD, turns the assembly horizontally a

whole revolution with signals transmitted through a rolling tape

configuration. The camera drive points the cameras in elevation, almost

straight up or down. A third motor points the Mini-TES fold mirrors and

protective shroud, up to 30° above the horizon and 50° below. The PMA's

conceptual design was done by Jason Suchman at JPL, the Cognizant

Engineer who later served as Contract Technical Manager (CTM) once the

assembly was built by Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp., Boulder, Colorado.

Raul Romero served as CTM once subsystem-level testing began. Satish

Krishnan did the conceptual design of the High-Gain Antenna Gimbal

(HGAG), whose detailed design, assembly, and test was also performed by

Ball Aerospace at which point Satish acted as the CTM.

Four monochromatic hazard cameras (Hazcams) are mounted on the rover's body, two in front and two behind.

The instrument deployment device (IDD), also called the rover arm, holds the following:

- Mössbauer spectrometer (MB) MIMOS II, developed by Dr. Göstar Klingelhöfer at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany, is used for close-up investigations of the mineralogy of iron-bearing rocks and soils.

- Alpha particle X-ray spectrometer (APXS), developed by the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz, Germany, is used for close-up analysis of the abundances of elements that make up rocks and soils. Universities involved in developing the APXS include the University of Guelph, University of California, and Cornell University

- Magnets, for collecting magnetic dust particles, developed by Jens Martin Knudsen's group at the Niels Bohr Institute, Copenhagen. The particles are analyzed by the Mössbauer Spectrometer and X-ray Spectrometer to help determine the ratio of magnetic particles to non-magnetic particles and the composition of magnetic minerals in airborne dust and rocks that have been ground by the Rock Abrasion Tool. There are also magnets on the front of the rover, which are studied extensively by the Mössbauer spectrometer.

- Microscopic Imager (MI) for obtaining close-up, high-resolution images of rocks and soils. Development was led by Ken Herkenhoff's team at the USGS Astrogeology Research Program.

- Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT), developed by Honeybee Robotics, for removing dusty and weathered rock surfaces and exposing fresh material for examination by instruments on board.

The robotic arm is able to place instruments directly up against rock and soil targets of interest.

Naming of Spirit and Opportunity

Sofi Collis with a model of Mars Exploration Rover

The Spirit and Opportunity rovers were named through a student essay competition. The winning entry was by Sofi Collis, a third-grade Russian-American student from Arizona.

I used to live in an orphanage. It was dark and cold and lonely. At night, I looked up at the sparkly sky and felt better. I dreamed I could fly there. In America, I can make all my dreams come true. Thank you for the 'Spirit' and the 'Opportunity.'

— Sofi Collis, age 9

Prior to this, during the development and building of the rovers, they were known as MER-1 (Opportunity) and MER-2 (Spirit). Internally, NASA also uses the mission designations MER-A (Spirit) and MER-B (Opportunity) based on the order of landing on Mars (Spirit first then Opportunity).

Test rovers

Rover team members simulate Spirit in a Martian sandtrap.

The Jet Propulsion Laboratory maintains a pair of rovers, the Surface System Test-Beds

(SSTB) at its location in Pasadena for testing and modeling of

situations on Mars. One test rover, SSTB1, weighing approximately 180

kilograms (400 lb), is fully instrumented and nearly identical to Spirit and Opportunity. Another test version, SSTB-Lite,

is identical in size and drive characteristics but does not include all

instruments. It weighs in at 80 kilograms (180 lb), much closer to the

weight of Spirit and Opportunity in the reduced gravity of Mars. These rovers were used in 2009 for a simulation of the incident in which Spirit became trapped in soft soil.

SAP software for image viewing

The NASA team uses a software application called SAP to view images collected from the rover, and to plan its daily activities. There is a version available to the public called Maestro.

Planetary science findings

Spirit Landing Site, Gusev Crater

Plains

Although

the Gusev crater appears from orbital images to be a dry lakebed, the

observations from the surface show the interior plains mostly filled

with debris. The rocks on the plains of Gusev are a type of basalt. They contain the minerals olivine, pyroxene, plagioclase,

and magnetite, and they look like volcanic basalt as they are

fine-grained with irregular holes (geologists would say they have

vesicles and vugs).

Much of the soil on the plains came from the breakdown of the local rocks. Fairly high levels of nickel were found in some soils; probably from meteorites.

Analysis shows that the rocks have been slightly altered by tiny amounts

of water. Outside coatings and cracks inside the rocks suggest water

deposited minerals, maybe bromine

compounds. All the rocks contain a fine coating of dust and one or more

harder rinds of material. One type can be brushed off, while another

needed to be ground off by the Rock Abrasion Tool (RAT).

There are a variety of rocks in the Columbia Hills, some of which have been altered by water, but not by very much water.

| |

| Coordinates: | 14.6°S 175.5°E |

|---|---|

These rocks can be classified in different ways. The amounts and

types of minerals make the rocks primitive basalts—also called picritic

basalts. The rocks are similar to ancient terrestrial rocks called

basaltic komatiites. Rocks of the plains also resemble the basaltic shergottites,

meteorites which came from Mars. One classification system compares the

amount of alkali elements to the amount of silica on a graph; in this

system, Gusev plains rocks lie near the junction of basalt, picrobasalt, and tephite. The Irvine-Barager classification calls them basalts.

Plain’s rocks have been very slightly altered, probably by thin films of

water because they are softer and contain veins of light colored

material that may be bromine compounds, as well as coatings or rinds. It

is thought that small amounts of water may have gotten into cracks

inducing mineralization processes).

Coatings on the rocks may have occurred when rocks were buried and interacted with thin films of water and dust.

One sign that they were altered was that it was easier to grind these rocks compared to the same types of rocks found on Earth.

The first rock that Spirit studied was Adirondack. It turned out to be typical of the other rocks on the plains.

Dust

The dust in Gusev Crater is the same as dust all around the planet. All the dust was found to be magnetic. Moreover, Spirit found the magnetism was caused by the mineral magnetite, especially magnetite that contained the element titanium. One magnet was able to completely divert all dust hence all Martian dust is thought to be magnetic. The spectra of the dust was similar to spectra of bright, low thermal inertia regions like Tharsis

and Arabia that have been detected by orbiting satellites. A thin layer

of dust, maybe less than one millimeter thick covers all surfaces.

Something in it contains a small amount of chemically bound water.

Columbia Hills

As the rover climbed above the plains onto the Columbia Hills, the mineralogy that was seen changed.

Scientists found a variety of rock types in the Columbia Hills, and

they placed them into six different categories. The six are: Clovis,

Wishbone, Peace, Watchtower, Backstay, and Independence. They are named

after a prominent rock in each group. Their chemical compositions, as

measured by APXS, are significantly different from each other. Most importantly, all of the rocks in Columbia Hills show various degrees of alteration due to aqueous fluids.

They are enriched in the elements phosphorus, sulfur, chlorine, and

bromine—all of which can be carried around in water solutions. The

Columbia Hills’ rocks contain basaltic glass, along with varying amounts

of olivine and sulfates.

The olivine abundance varies inversely with the amount of sulfates. This

is exactly what is expected because water destroys olivine but helps to

produce sulfates.

The Clovis group is especially interesting because the Mössbauer spectrometer (MB) detected goethite in it.

Goethite forms only in the presence of water, so its discovery is the

first direct evidence of past water in the Columbia Hills's rocks. In

addition, the MB spectra of rocks and outcrops displayed a strong

decline in olivine presence,

although the rocks probably once contained much olivine.

Olivine is a marker for the lack of water because it easily decomposes

in the presence of water. Sulfate was found, and it needs water to

form.

Wishstone contained a great deal of plagioclase, some olivine, and anhydrate (a sulfate). Peace rocks showed sulfur

and strong evidence for bound water, so hydrated sulfates are

suspected. Watchtower class rocks lack olivine consequently they may

have been altered by water. The Independence class showed some signs of

clay (perhaps montmorillonite a member of the smectite group). Clays

require fairly long term exposure to water to form.

One type of soil, called Paso Robles, from the Columbia Hills, may be an

evaporate deposit because it contains large amounts of sulfur, phosphorus, calcium, and iron.

Also, MB found that much of the iron in Paso Robles soil was of the oxidized, Fe3+ form.

Towards the middle of the six-year mission (a mission that was supposed to last only 90 days), large amounts of pure silica

were found in the soil. The silica could have come from the interaction

of soil with acid vapors produced by volcanic activity in the presence

of water or from water in a hot spring environment.

After Spirit stopped working scientists studied old data from the Miniature Thermal Emission Spectrometer, or Mini-TES and confirmed the presence of large amounts of carbonate-rich

rocks, which means that regions of the planet may have once harbored

water. The carbonates were discovered in an outcrop of rocks called

"Comanche."

In summary, Spirit found evidence of slight weathering on

the plains of Gusev, but no evidence that a lake was there. However, in

the Columbia Hills there was clear evidence for a moderate amount of

aqueous weathering. The evidence included sulfates and the minerals

goethite and carbonates which only form in the presence of water. It is

believed that Gusev crater may have held a lake long ago, but it has

since been covered by igneous materials. All the dust contains a

magnetic component which was identified as magnetite with some titanium.

Furthermore, the thin coating of dust that covers everything on Mars is

the same in all parts of Mars.

Opportunity Landing Site, Meridiani Planum

Self-portrait of Opportunity near Endeavor Crater on the surface of Mars (January 6, 2014).

Cape Tribulation southern end, as seen in 2017 by Opportunity rover

The Opportunity rover landed in a small crater, dubbed

"Eagle", on the flat plains of Meridiani. The plains of the landing site

were characterized by the presence of a large number of small spherules, spherical concretions

that were tagged "blueberries" by the science team, which were found

both loose on the surface, and also embedded in the rock. These proved

to have a high concentration of the mineral hematite,

and showed the signature of being formed in an aqueous environment. The

layered bedrock revealed in the crater walls showed signs of being

sedimentary in nature, and compositional and microscopic-imagery

analysis showed this to be primarily with composition of Jarosite, a ferrous sulfate mineral that is characteristically an evaporite that is the residue from the evaporation of a salty pond or sea.

The mission has provided substantial evidence of past water

activity on Mars. In addition to investigating the "water hypothesis", Opportunity

has also obtained astronomical observations and atmospheric data.

The extended mission took the rover across the plains to a series of

larger craters in the south, with the arrival at the edge of a 25-km

diameter crater, Endeavor Crater, eight years after landing. The

orbital spectroscopy of this crater rim show the signs of phyllosilicate rocks, indicative of older sedimentary deposits.