Contemporary characterizations

The

term secular religion is often applied today to communal belief

systems—as for example with the view of love as our postmodern secular

religion. Paul Vitz applied the term to modern psychology in as much as it fosters a cult of the self, explicitly calling "the self-theory ethic [...] this secular religion". Sport has also been considered as a new secular religion, particularly with respect to Olympism. For Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympic Games, belief in them as a new secular religion was explicit and lifelong.

Political religion

The theory of political religion concerns governmental ideologies whose cultural and political backing is so strong that they are said to attain power equivalent to those of a state religion, with which they often exhibit significant similarities in both theory and practice.

In addition to basic forms of politics, like parliament and elections,

it also holds an aspect of "sacralization" related to the institutions

contained within the regime and also provides the inner measures

traditionally considered to be religious territory, such as ethics, values, symbols, myths, rituals, archetypes and for example a national liturgical calendar.

Political religious organizations, such as the Nazi Party,

adhered to the idealization of cultural and political power over the

country at large. The church body of the state no longer held control

over the practices of religious identity. Because of this, Nazism was

countered by many political and religious organizations as being a

political religion, based on the dominance which the Nazi regime had

(Gates and Steane).

Political religions generally vie with existing traditional religions,

and may try to replace or eradicate them. The term was given new

attention by the political scientist Hans Maier.

Totalitarian societies are perhaps more prone to political religion, but various scholars have described features of political religion even in democracies, for instance American civil religion as described by Robert Bellah in 1967.

The term is sometimes treated as synonymous with civil religion,

but although some scholars use the terms equivalently, others see a

useful distinction, using "civil religion" as something weaker, which

functions more as a socially unifying and essentially conservative

force, whereas a political religion is radically transformational, even apocalyptic.

Overview

The term political religion

is based on the observation that sometimes political ideologies or

political systems display features more commonly associated with religion. Scholars who have studied these phenomena include William Connolly in political science, Christoph Deutschmann in sociology, Emilio Gentile in history, Oliver O'Donovan in theology and others in psychology.

A political religion often occupies the same ethical, psychological and

sociological space as a traditional religion, and as a result it often

displaces or co-opts existing religious organizations and beliefs. The

most central marker of a political religion involves the sacralization of politics, for example an overwhelming religious feeling when serving one's country, or the devotion towards the Founding Fathers of the United States. Although a political religion may co-opt existing religious structures or symbolism, it does not itself have any independent spiritual or theocratic

elements—it is essentially secular, using religious motifs and methods

for political purposes, if it does not reject religious faith outright. Typically, a political religion is considered to be secular, but more radical forms of it are also transcendental.

Origin of the theory

The 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau

(1712–1778) argued that all societies need a religion to hold men

together. Because Christianity tended to pull men away from earthly

matters, Rousseau advocated a "civil religion" that would create the

links necessary for political unity around the state. The Swiss

Protestant theologian Adolf Keller (1872–1963) argued that Marxism in the Soviet Union had been transformed into a secular religion. Before emigrating to the United States, the German-born political philosopher Eric Voegelin wrote a book entitled The political religions.

Other contributions on "political religion" (or associated terms such

as "secular religion", "lay religion" or "public religion") were made by

Luigi Sturzo (1871–1959), Paul Tillich (1886–1965), Gerhard Leibholz (1901–1982), Waldemar Gurian (1902–1954), Raymond Aron (1905–1983) and Walter Benjamin (1892–1940). Some saw such "religions" as a response to the existential void and nihilism caused by modernity, mass society

and the rise of a bureaucratic state, and in political religions "the

rebellion against the religion of God" reached its climax. They

also described them as "pseudo-religions", "substitute religions",

"surrogate religions", "religions manipulated by man" and

"anti-religions". Yale political scientist Juan Linz

and others have noted that the secularization of the twentieth century

had created a void which could be filled by an ideology claiming a hold

on ethical and identical matters as well, making the political religions

based on totalitarianism, universalism and messianic missions (such as Manifest Destiny) possible.

An academic journal with the name Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions started publication in 2000. It was renamed Politics, Religion & Ideology in 2011. It is published by Taylor & Francis.

Typical aspects

Key qualities often (not all are always present) shared by political religion include:

- Structural

- Differentiation between self and other, and demonization of other (in theistic religion, the differentiation usually depends on adherence to certain dogmas and social behaviors; in political religion, differentiation may be on grounds such as nationality, social attitudes, or membership in "enemy" political parties, instead).

- A transcendent leadership, either with messianic tendencies, often a charismatic figurehead.

- Strong, hierarchical organizational structures.

- The control of education, in order to ensure the security, continuation and the veneration of the existing system.

- Belief

- A coherent belief system for imposing symbolic meaning on the external world, with an emphasis on security through faith in the system.

- An intolerance of other ideologies of the same type.

- A degree of utopianism.

- The belief that the ideology is in some way natural or obvious, so that (at least for certain groups of people) those who reject it are in some way "blind".

- A genuine desire on the part of individuals to convert others to the cause.

- A willingness to place ends over means—in particular, a willingness (for some) to use violence or/and fraud.

- Fatalism—a belief that the ideology will inevitably triumph in the end.

Not all of these aspects are present in any one political religion; this is only a list of some common aspects.

Suppression of religious beliefs

Political religions compete with existing religions, and try, if possible, to replace or eradicate them.

Loyalty to other entities, such as a church or a deity are often

viewed as interfering with loyalty to the political religion. The

authority of potential religious leaders also presents a threat to the

authority of the political religion. As a result, some or all religious

sects may be suppressed or banned. An existing sect may be converted

into a state religion,

but dogma and personnel may be modified to suit the needs of the party

or state. Where there is suppression of religious institutions and

beliefs, this might be explicitly accompanied by atheistic doctrine as in state atheism.

Juan Linz has posited the friendly form of separation of church and state

as the opposite pole of political religion but describes the hostile form

of separation of church and state as moving toward political religion

as found in totalitarianism.

Absolute loyalty

Loyalty

to the state or political party and acceptance of the government/party

ideology are paramount. Dissenters may be expelled, ostracized,

discriminated against, imprisoned, "re-educated", or killed. Loyalty oaths

or membership in a dominant (or sole) political party may be required

for employment, government services, or simply as routine. Criticism of

the government may be a serious crime. Enforcements range from

ostracism by one's neighbors to execution. In a fundamental political

religion you are either with the system or against it.

Cult of personality

A political religion often elevates its leaders to near-godlike

status. Displays of leaders in the form of posters or statues may be

mandated in public areas and even private homes. Children may be

required to learn the state's version of the leaders' biographies in

school.

Myths of origin

Political religions often rely on a myth of origin

that may have some historical basis but is usually idealized and

sacralized. Current leaders may be venerated as descendants of the

original fathers. There may also be holy places or shrines that relate

to the myth of origin.

Historical cases

Revolutionary France

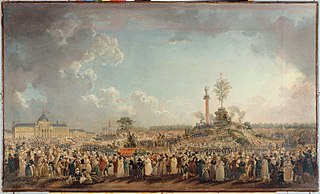

The Festival of the Supreme Being,

by Pierre-Antoine Demachy.

by Pierre-Antoine Demachy.

Revolutionary France was well noted for being the first state to reject religion altogether. Radicals intended to replace Christianity with a new state religion, or an atheistic ideology. Maximilien Robespierre rejected atheistic ideologies and intended to create a new religion. Churches were closed, and Catholic Mass was forbidden. The Cult of the Supreme Being was well known for its derided festival, which led to the Thermidorian reaction and the fall of Robespierre.

Fascism

Italian fascism

According to Emilio Gentile, "Fascism was the first and prime instance of a modern political religion."

"This religion sacralized the state and assigned it the primary

educational task of transforming the mentality, the character, and the

customs of Italians. The aim was to create a 'new man', a believer in and an observing member of the cult of Fascism."

"The argument [that fascism was a ‘political religion’] tends to

involve three main claims: I) that fascism was characterized by a

religious form, particularly in terms of language and ritual; II) that

fascism was a sacralized form of totalitarianism, which legitimized

violence in defense of the nation and regeneration of a fascist 'new

man'; and III) that fascism took on many of the functions of religion

for a broad swathe of society."

Nazi Germany

"Among committed [Nazi] believers, a mythic world of eternally strong

heroes, demons, fire and sword—in a word, the fantasy world of the

nursery—displaced reality." Heinrich Himmler was fascinated by the occult, and sought to turn the SS into the basis of an official state cult.

Soviet Union

In 1936 a Protestant priest referred explicitly to communism as a new secular religion. A couple of years later, on the eve of World War II, F. A. Voigt characterized both Marxism and National Socialism as secular religions, akin at a fundamental level in their authoritarianism and messianic beliefs as well as in their eschatological view of human History. Both, he considered, were waging religious war against the liberal enquiring mind of the European heritage.

After the war, the social philosopher Raymond Aron would expand on the exploration of communism in terms of a secular religion; while A. J. P. Taylor, for example, would characterize it as "a great secular religion....the Communist Manifesto must be counted as a holy book in the same class as the Bible".

Klaus-Georg Riegel argued that "Lenin's utopian design of a

revolutionary community of virtuosi as a typical political religion of

an intelligentsia longing for an inner-worldly salvation, a socialist

paradise without exploitation and alienation, to be implanted in the

Russian backward society at the outskirts of the industrialized and

modernized Western Europe."

Modern examples

North Korea

The North Korean government has promulgated Juche

as a political alternative to traditional religion. The doctrine

advocates a strong nationalist propaganda basis and is fundamentally

opposed to Christianity and Buddhism,

the two largest religions on the Korean peninsula. Juche theoreticians

have, however, incorporated religious ideas into the state ideology. According to government figures, Juche is the largest political religion in North Korea. The public practice of all other religions is overseen and subject to heavy surveillance by the state.

Turkmenistan

During the long rule of president Saparmurat Niyazov large pictures and statues of him could be seen in public places in Turkmenistan.

In an interview with the television news program "60 Minutes", Niyazov

said the people of Turkmenistan placed them there voluntarily because

they love him so much, and that he did not originally want them there.

In addition, he granted himself the title "Türkmenbaşy", meaning "Leader

of all Ethnic Turkmens" in the Turkmen language. A book purportedly authored by Niyazov, Ruhnama

("Book of the Soul") was required reading in educational institutions

and was often displayed and treated with the same respect as the Qur'an.

The study of Ruhnama in the academic system was scaled down but to some

extent continued after Niyazov's death (in 2006), as of 2008.

Lebanon

Since its foundation in 1982, Hezbollah, the Shi'a Islamist political party and paramilitary group has produced public media

in order to maintain the Lebanese population under a permanent state of

order. The nominally terrorist organization that now has Members in the

Parliament and the government uses European-inspired techniques such as

the cult of personality, cult of martyrdom, antisemitism and conspirationnism.

Latest example of terror is dated from October 2017 when angry citizens

criticized Hezbollah's leader and political allies before being forced

into apologizing publicly in a humiliating way.