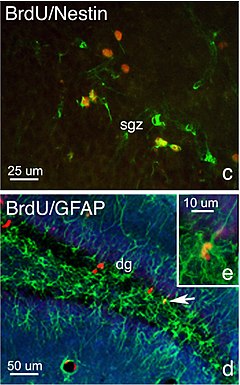

BrdU (red), a marker of DNA replication, highlights neurogenesis in the subgranular zone of hippocampal dentate gyrus. Fragment of an illustration from Faiz et al., 2005.

Doublecortin expression in the rat dentate gyrus, 21st postnatal day. Oomen et al., 2009.

Adult neurogenesis is the process by which neurons are generated from neural stem cells in the adult. This process is different from the embryonic development of neurogenesis.

In most mammals, new neurons are continually born throughout adulthood in two regions of the brain:

- The subgranular zone (SGZ), part of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, where neural stem cells give birth to granule cells (implicated in memory formation and learning).

- The subventricular zone (SVZ) of the lateral ventricles, can be divided into three microdomains – lateral, dorsal and medial). Neural stem cells migrate to the olfactory bulb through the rostral migratory stream where they differentiate into interneurons participating in the sense of smell. In humans, however, few if any olfactory bulb neurons are generated after birth.

More attention has been given to neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus than in the striatum. In rodents, many of the newborn dentate gyrus neurons die shortly after they are born, but a number of them become functionally integrated into the surrounding brain tissue.

The amount of neurons born in the human hippocampus remains

controversial; some studies have reported that in adult humans about 700

new neurons are added in the hippocampus every day,

while other studies show that adult hippocampal neurogenesis does not

exist in humans, or, if it does, it is at undetectable levels.

The role of new neurons in adult brain function thus remains unclear.

Adult neurogenesis is reported to play a role in learning and memory,

emotion, stress, depression, response to injury, and other conditions.

Mechanism

Adult neural stem cells

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are the self-renewing, multipotent cells that generate the main phenotypes of the nervous system.

Lineage reprogramming (trans-differentiation)

Emerging

evidence suggests that neural microvascular pericytes, under

instruction from resident glial cells, are reprogrammed into

interneurons and enrich local neuronal microcircuits. This response is amplified by concomitant angiogenesis.

Model organisms of neurogenesis

Planarian

Planarian are one of the earliest model organisms used to study regeneration with Pallas

as the forefather of planarian studies. Planarian are a classical

invertebrate model that in recent decades have been used to examine

neurogenesis. The central nervous system of a planarian is simple,

though fully formed with two lobes located in the head and two ventral nerve cords.

This model reproduces asexually producing a complete and fully

functioning nervous system after division allowing for consistent

examination of neurogenesis.

Axolotl

The

axolotl is less commonly used than other vertebrates, but is still a

classical model for examining regeneration and neurogenesis. Though the

axolotl has made its place in biomedical research in terms of limb

regeneration, the model organism has displayed a robust ability to generate new neurons following damage.

Axolotls have contributed as a bridge organism between invertebrates

and mammals, as the species has the regenerative capacity to undergo

complete neurogenesis forming a wide range of neuronal populations not

limited to a small niche, yet the complexity and architecture is complex and analogous in many ways to human neural development.

Zebrafish

Zebrafish have long been a classical developmental model due to their transparency during organogenesis and have been utilized heavily in early development neurogenesis.).

The zebrafish displays a strong neurogenerative capacity capable of

regenerating a variety of tissues and complete neuronal diversity (with

the exception of astrocytes,

as they have yet to be identified within the zebrafish brain) with

continued neurogenesis through the life span. In recent decades the

model has solidified its role in adult regeneration and neurogenesis

following damage.

The zebrafish, like the axolotl, has played a key role as a bridge

organism between invertebrates and mammals. The zebrafish is a rapidly

developing organism that is relatively inexpensive to maintain, while

providing the field ease of genetic manipulation and a complex nervous

system.

Chick

Though

avians have been used primarily to study early embryonic development,

in recent decades the developing chick has played a critical role in the

examination of neurogenesis and regeneration as the young chick is

capable of neuronal-turnover at a young age, but loses the

neurogenerative capacity into adulthood.

The loss of neuroregenerative ability over maturation has allowed

investigators to further examine genetic regulators of neurogenesis.

Rodent

Rodents, mice and rats, have been the most prominent model organism since the discovery of modern neurons by Santiago Ramon y Cajal.

Rodents have a very similar architecture and a complex nervous system

with very little regenerative capacity similar to that found in humans.

For that reason, rodents have been heavily used in pre-clinical testing.

Rodents display a wide range of neural circuits responsible for complex

behaviors making them ideal for studies of dendritic pruning and axonal

shearing.

While the organism makes for a strong human analog, the model has its

limitations not found in the previous models: higher cost of

maintenance, lower breeding numbers, and the limited neurogenerative

abilities.

Tracking neurogenesis

The creation of new functional brain cells can be measured in several ways, summarized in the following sections.

DNA labelling

Labelled DNA can trace dividing cell's lineage, and determine the location of its daughter cells. A nucleic acid analog is inserted into the genome of a neuron-generating cell (such as a glial cell or neural stem cell). Thymine analogs (3H) thymidine and BrdU are commonly used DNA labels, and are used for radiolabelling and immunohistochemistry respectively.

Fate determination via neuronal lineage markers

DNA labeling can be used in conjunction with neuronal lineage markers to determine the fate of new functional brain cells. First, incorporated labeled nucleotides are used to detect the populations of newly divided daughter cells. Specific cell types are then determined with unique differences in their expression of proteins, which can be used as antigens in an immunoassay. For example, NeuN/Fox3 and GFAP are antigens commonly used to detect neurons, glia, and ependymal cells. Ki67 is the most commonly used antigen to detect cell proliferation.

Some antigens can be used to measure specific stem cell stages. For example, stem cells requires the sox2 gene to maintain pluripotency and is used to detect enduring concentrations of stem cells in CNS tissue. The protein nestin is an intermediate filament, which is essential for the radial growth of axons, and is therefore used to detect the formation of new synapses.

Cre-Lox recombination

Some genetic tracing studies utilize cre-lox recombination to bind a promoter to a reporter gene, such as lacZ or GFP gene.

This method can be used for long term quantification of cell division

and labeling, whereas the previously mentioned procedures are only

useful for short-term quantification.

Viral Vectors

It has recently become more common to use recombinant viruses to insert the genetic information encoding specific markers (usually protein fluorophores such as GFP) that are only expressed in cells of a certain kind. The marker gene is inserted downstream of a promoter, leading to transcription of that marker only in cells containing the transcription factor(s) that bind to that promoter. For example, a recombinant plasmid may contain the promoter for doublecortin, a protein expressed predominantly by neurons, upstream of a sequence coding for GFP, thereby making infected cells fluoresce green upon exposure to light in the blue to ultraviolet range while leaving non doublecortin expressing cells unaffected, even if they contain the plasmid.

Many cells will contain multiple copies of the plasmid and the

fluorphore itself, allowing the fluorescent properties to be transferred

along an infected cell's lineage.

By labeling a cell that gives rise to neurons, such as a neural stem cells or neural precursor cells, one can track the creation, proliferation, and even migration of newly created neurons.

It is important to note, however, that while the plasmid is stable for

long periods of time, its protein products may have highly variable half lives

and their fluorescence may decrease as well as become too diluted to be

seen depending on the number of round of replication they have

undergone, making this method more useful for tracking self-similar

neural precursor or neural stem cells rather than neurons themselves.

The insertion of genetic material via a viral vector tends to be sporadic and infrequent relative to the total number of cells in a given region of tissue,

making quantification of cell division inaccurate. However, the above

method can provide highly accurate data with respect to when a cell was born as well as full cellular morphologies.

Methods for inhibiting neurogenesis

Many

studies analyzing the role of adult neurogenesis utilize a method of

inhibiting cell proliferation in specific brain regions, mimicking an

inhibition of neurogenesis, to observe the effects on behavior.

Pharmacological inhibition

Pharmacological

inhibition is widely used in various studies, as it provides many

benefits. It is generally inexpensive as compared to other methods, such

as irradiation, can be used on various species, and does not require

any invasive procedures or surgeries for the subjects.

However, it does pose certain challenges, as these inhibitors

can't be used to inhibit proliferation in specific regions, thus leading

to nonspecific effects from other systems being affected. To avoid

these effects, more work must be done to determine optimal doses in

order to minimize the effects on systems unrelated to neurogenesis.

A common pharmacological inhibitor for adult neurogenesis is

methylazoxymethanol acetate (MAM), a chemotherapeutic agent. Other cell

division inhibitors commonly used in studies are cytarabine and

temozolomide.

Pharmacogenetics

Another

method used to study the effects of adult neurogenesis is using

pharmacogenetic models. These models provide different benefits from the

pharmacological route, as it allows for more specificity by targeting

specific precursors to neurogenesis and specific stem cell promoters. It

also allows for temporal specificity with the interaction of certain

drugs. This is beneficial in looking specifically at neurogenesis in

adulthood, after normal development of other regions in the brain.

The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK) has been used

in studies in conjunction with antiviral drugs to inhibit adult

neurogenesis. It works by targeting stem cells using glial fibrillary

acidic proteins and nestin expression. These targeted stem cells undergo

cell death instead of cell proliferation when exposed to antiviral

drugs.

Cre protein is also commonly used in targeting stem cells that will undergo gene changes upon treatment with tamoxifen.

Irradiation

Irradiation

is a method that allows for very specific inhibition of adult

neurogenesis. It can be targeted to the brain to avoid affecting other

systems and having nonspecific effects. It can even be used to target

specific brain regions, which is important in determining how adult

neurogenesis in different areas of the brain affects behavior.

However, irradiation is more expensive than the other methods and also requires large equipment with trained individuals.

Inhibition of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus

Many studies have observed how inhibiting adult neurogenesis in other mammals, such as rats and mice, affect their behavior.

Inhibition of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus has been shown to

have various affects on learning and memory, conditioning, and

investigative behaviors.

Impaired fear conditioning has been seen in studies involving rats with a lack of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

Inhibition of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus has also been

linked to changes in behavior in tasks involving investigation.

Rats also show decreased contextualized freezing behaviors in response

to contextualized fear and impairment in learning spatial locations when

lacking adult neurogenesis.

Effects on pattern separation

The

changes in learning and memory seen in the studies mentioned previously

are thought to be related to the role of adult neurogenesis in

regulating pattern separation.

Pattern separation is defined as, "a process to remove redundancy from

similar inputs so that events can be separated from each other and

interference can be reduced, and in addition can produce a more

orthogonal, sparse, and categorized set of outputs."

This impairment in pattern separation could explain the

impairments seen in other learning and memory tasks. A decreased ability

in reducing interference could lead to greater difficulty in forming

and retaining new memories,

although it's hard to discriminate between effects of neurogenesis in

learning and pattern separation due to limitations in the interpretation

behavioral results."

Studies show that rats with inhibited adult neurogenesis

demonstrate difficulty in differentiating and learning contextualized

fear conditioning.

Rats with blocked adult neurogenesis also show impaired differential

freezing when they are required to differentiate between similar

contexts.

This also affects their spatial recognition in radial arm maze tests

when the arms are closer together rather than when they are further

apart.

A meta-analysis of behavioral studies evaluating the effect of

neurogenesis in different pattern separation tests has shown a

consistent effect of neurogenesis ablation on performance, although

there are exceptions in the literature."

Effects on behavioral inhibition

Behavioral

inhibition is important in rats and other animals in halting whatever

they are currently doing in order to reassess a situation in response to

a threat or anything else that may require their attention.

Rats with lesioned hippocampi show less behavioral inhibition when exposed to threats, such as cat odor.

The disruption of normal cell proliferation and development of the

dentate gyrus in developing rats also impairs their freezing response,

which is an example of behavior inhibition, when exposed to an

unfamiliar adult male rat.

This impairment in behavioral inhibition also ties into the

process of learning and memory, as repressing wrong answers or behaviors

requires the ability to inhibit that response.

Implications

Role in learning

The functional relevance of adult neurogenesis is uncertain, but there is some evidence that hippocampal adult neurogenesis is important for learning and memory.

Multiple mechanisms for the relationship between increased neurogenesis

and improved cognition have been suggested, including computational

theories to demonstrate that new neurons increase memory capacity, reduce interference between memories, or add information about time to memories.

Experiments aimed at ablating neurogenesis have proven inconclusive,

but several studies have proposed neurogenic-dependence in some types of

learning, and others seeing no effect. Studies have demonstrated that the act of learning itself is associated with increased neuronal survival. However, the overall findings that adult neurogenesis is important for any kind of learning are equivocal.

Alzheimer's disease

Some studies suggest that decreased hippocampal neurogenesis can lead to development of Alzheimer's disease (AD).

Yet, others hypothesize that AD patients have increased neurogenesis in

the CA1 region of Ammon's horn (the principal region of AD hippocampal

pathology) in order to compensate for neuronal loss. While the exact nature of the relationship between neurogenesis and Alzheimer's disease is unknown, insulin-like growth factor 1-stimulated neurogenesis produces major changes in hippocampal plasticity and seems to be involved in Alzheimer's pathology. Allopregnanolone, a neurosteroid, aids the continued neurogenesis in the brain. Levels of allopregnanolone in the brain decline in old age and Alzheimer's disease. Allopregnanolone has been shown through reversing impairment of neurogenesis to reverse the cognitive deficits in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Eph receptors and ephrin signaling have been shown to regulate adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus and have been studied as potential targets to treat some symptoms of AD. Molecules associated with the pathology of AD, including ApoE, PS1 and APP, have also been found to impact adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus.

Role in schizophrenia

Studies suggest that people with schizophrenia

have a reduced hippocampus volume, which is believed to be caused by a

reduction of adult neurogenesis. Correspondingly, this phenomenon might

be the underlying cause of many of the symptoms of the disease.

Furthermore, several research papers referred to four genes,

dystrobrevin binding protein 1 (DTNBP1), neuregulin 1 (NRG1), disrupted

in schizophrenia 1 (DISC1), and neuregulin 1 receptor (ERBB4), as being

possibly responsible for this deficit in the normal regeneration of

neurons.

Similarities between depression and schizophrenia suggest a possible

biological link between the two diseases. However, further research must

be done in order to clearly demonstrate this relationship.

Adult Neurogenesis and Major Depressive Disorder

Research indicates that adult hippocampal neurogenesis is inversely related to Major Depressive Disorder (MDD).

Neurogenesis is decreased in the hippocampus of animal models of major

depressive disorder, and many treatments for the disorder, including antidepressant medication and electroconvulsive therapy,

increase hippocampal neurogenesis. It has been theorized that decreased

hippocampal neurogenesis in individuals with major depressive disorder

may be related to the high levels of stress hormones called glucocorticoids, which are also associated with the disorder. The hippocampus instructs the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

to produce less glucocorticoids when glucocorticoid levels are high. A

malfunctioning hippocampus, therefore, might explain the chronically

high glucocorticoid levels in individuals with major depressive

disorder. However, some studies have indicated that hippocampal

neurogenesis is not lower in individuals with major depressive disorder

and that blood glucocorticoid levels do not change when hippocampal

neurogenesis changes, so the associations are still uncertain.

Stress and depression

Many now believe stress to be the most significant factor for the onset of depression,

aside from genetics. As discussed above, hippocampal cells are

sensitive to stress which can lead to decreased neurogenesis. This area

is being considered more frequently when examining the causes and

treatments of depression. Studies have shown that removing the adrenal gland in rats caused increased neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus. The adrenal gland is responsible for producing cortisol in response to a stressor, a substance that when produced in chronic amounts causes the down regulation of serotonin receptors and suppresses the birth of neurons.

It was shown in the same study that administration of corticosterone to

normal animals suppressed neurogenesis, the opposite effect. The most typical class of antidepressants administered for this disease are selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and their efficacy may be explained by neurogenesis. In a normal brain, an increase in serotonin causes suppression of the corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) through connection to the hippocampus. It directly acts on the paraventricular nucleus to decrease CRH release and down regulate norepinephrine functioning in the locus coeruleus.

Because CRH is being repressed, the decrease in neurogenesis that is

associated with elevated levels of it is also being reversed. This

allows for the production of more brain cells, in particular at the

5-HT1a receptor in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus which has been

shown to improve symptoms of depression. It normally takes neurons

approximately three to six weeks to mature,

which is approximately the same amount of time it takes for SSRIs to

take effect. This correlation strengthens the hypothesis that SSRIs act

through neurogenesis to decrease the symptoms of depression. Some

neuroscientists have expressed skepticism that neurogenesis is

functionally significant, given that a tiny number of nascent neurons

are actually integrated into existing neural circuitry. However, a

recent study used the irradiation of nascent hippocampal neurons in

non-human primates (NHP) to demonstrate that neurogenesis is required

for antidepressant efficacy.

Adult-born neurons appear to have a role in the regulation of stress. Studies have linked neurogenesis to the beneficial actions of specific antidepressants, suggesting a connection between decreased hippocampal neurogenesis and depression. In a pioneer study, scientists demonstrated that the behavioral benefits of antidepressant administration in mice is reversed when neurogenesis is prevented with x-irradiation techniques. In fact, newborn neurons are more excitable than older neurons due to a differential expression of GABA receptors.

A plausible model, therefore, is that these neurons augment the role of

the hippocampus in the negative feedback mechanism of the HPA-axis (physiological stress) and perhaps in inhibiting the amygdala (the region of brain responsible for fearful responses to stimuli). Indeed, suppression of adult neurogenesis can lead to an increased HPA-axis stress response in mildly stressful situations.

This is consistent with numerous findings linking stress-relieving

activities (learning, exposure to a new yet benign environment, and

exercise) to increased levels of neurogenesis, as well as the

observation that animals exposed to physiological stress (cortisol) or psychological stress

(e.g. isolation) show markedly decreased levels of newborn neurons.

Under chronic stress conditions, the elevation of newborn neurons by

antidepressants improves the hippocampal-dependent control on the stress

response; without newborn neurons, antidepressants are unable to

restore the regulation of the stress response and recovery becomes

impossible.

Some studies have hypothesized that learning and memory are linked to depression, and that neurogenesis may promote neuroplasticity. One study proposes that mood may be regulated, at a base level, by plasticity, and thus not chemistry. Accordingly, the effects of antidepressant treatment would only be secondary to change in plasticity.

However another study has demonstrated an interaction between

antidepressants and plasticity; the antidepressant fluoxetine has been

shown to restore plasticity in the adult rat brain.

The results of this study imply that instead of being secondary to

changes in plasticity, antidepressant therapy could promote it.

Effects of sleep reduction

One

study has linked lack of sleep to a reduction in rodent hippocampal

neurogenesis. The proposed mechanism for the observed decrease was

increased levels of glucocorticoids. It was shown that two weeks of sleep deprivation

acted as a neurogenesis-inhibitor, which was reversed after return of

normal sleep and even shifted to a temporary increase in normal cell

proliferation.

More precisely, when levels of corticosterone are elevated, sleep

deprivation inhibits this process. Nonetheless, normal levels of

neurogenesis after chronic sleep deprivation return after 2 weeks, with a

temporary increase of neurogenesis.

While this is recognized, overlooked is the blood glucose demand

exhibited during temporary diabetic hypoglycemic states. The American

Diabetes Association amongst many documents the pseudosenilia and

agitation found during temporary hypoglycemic states. Much more

clinical documentation is needed to competently demonstrate the link

between decreased hematologic glucose and neuronal activity and mood.

Possible use in treating Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Transplantation of fetal dopaminergic precursor cells has paved the way for the possibility of a cell replacement therapy that could ameliorate clinical symptoms in affected

patients.

In recent years, scientists have provided evidence for the existence of

neural stem cells with the potential to produce new neurons,

particularly of a dopaminergic phenotype, in the adult mammalian brain.

Experimental depletion of dopamine in rodents decreases precursor cell

proliferation in both the subependymal zone and the subgranular zone. Proliferation is restored completely by a selective agonist of D2-like (D2L) receptors.

Neural stem cells have been identified in the neurogenic brain

regions, where neurogenesis is constitutively ongoing, but also in the

non-neurogenic zones, such as the midbrain and the striatum, where

neurogenesis is not thought to occur under normal physiological

conditions. Newer research has shown that there in fact is neurogenesis in the striatum.

A detailed understanding of the factors governing adult neural stem cells in vivo

may ultimately lead to elegant cell therapies for neurodegenerative

disorders such as Parkinson's disease by mobilizing autologous

endogenous neural stem cells to replace degenerated neurons.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Traumatic brain injuries vary in their mechanism of injury, producing a blunt or penetrating trauma resulting in a primary and secondary injury with excitotoxicity and relatively wide spread neuronal death. Due to the overwhelming number of traumatic brain injuries as a result of the War on Terror,

tremendous amounts of research have been placed towards a better

understanding of the pathophysiology of traumatic brain injuries as well

as neuroprotective

interventions and possible interventions prompting restorative

neurogenesis. Hormonal interventions, such as progesterone, estrogen,

and allopregnanolone have been examined heavily in recent decades as

possible neuroprotective agents following traumatic brain injuries to

reduce the inflammation response stunt neuronal death.

In rodents, lacking the regenerative capacity for adult neurogenesis,

the activation of stem cells following administration of α7 nicotinic

acetylcholine receptor agonist, PNU-282987,

has been identified in damaged retinas with follow-up work examining

activation of neurogenesis in mammals after traumatic brain injury. Currently, there is no medical intervention that has passed phase-III clinical trials for use in the human population.

Factors affecting

Changes in old age

Neurogenesis

is substantially reduced in the hippocampus of aged animals, raising

the possibility that it may be linked to age-related declines in

hippocampal function. For example, the rate of neurogenesis in aged

animals is predictive of memory. However, new born cells in aged animals are functionally integrated.

Given that neurogenesis occurs throughout life, it might be expected

that the hippocampus would steadily increase in size during adulthood,

and that therefore the number of granule cells would be increased in

aged animals. However, this is not the case, indicating that

proliferation is balanced by cell death. Thus, it is not the addition of

new neurons into the hippocampus that seems to be linked to hippocampal

functions, but rather the rate of turnover of granule cells.

Effects of exercise

Scientists have shown that physical activity in the form of voluntary

exercise results in an increase in the number of newborn neurons in the

hippocampus of mice and rats. These and other studies have shown that learning in both species can be enhanced by physical exercise. Recent research has shown that brain-derived neurotrophic factor and insulin-like growth factor 1 are key mediators of exercise-induced neurogenesis. Exercise increases the production of BDNF, as well as the NR2B subunit of the NMDA receptor.

Exercise increases the uptake of IGF-1 from the bloodstream into

various brain regions, including the hippocampus. In addition, IGF-1

alters c-fos expression in the hippocampus. When IGF-1 is blocked,

exercise no longer induces neurogenesis.

Other research demonstrated that exercising mice that did not produce

beta-endorphin, a mood-elevating hormone, had no change in neurogenesis.

Yet, mice that did produce this hormone, along with exercise, exhibited

an increase in newborn cells and their rate of survival.

While the association between exercise-mediated neurogenesis and

enhancement of learning remains unclear, this study could have strong

implications in the fields of aging and/or Alzheimer's disease.

Effects of cannabinoids

Some studies have shown that the stimulation of the cannabinoids

results in the growth of new nerve cells in the hippocampus from both

embryonic and adult stem cells. In 2005 a clinical study of rats at the

University of Saskatchewan showed regeneration of nerve cells in the

hippocampus. Studies have shown that a synthetic drug resembling THC, the main psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, provides some protection against brain inflammation,

which might result in better memory at an older age. This is due to

receptors in the system that can also influence the production of new

neurons.

Nonetheless, a study directed at Rutgers University demonstrated how

synchronization of action potentials in the hippocampus of rats was

altered after THC administration. Lack of synchronization corresponded

with impaired performance in a standard test of memory.

Recent studies indicate that a natural cannabinoid of cannabis,

cannabidiol (CBD), increases adult neurogenesis while having no effect

on learning. THC however impaired learning and had no effect on

neurogenesis.

A greater CBD to THC ratio in hair analyses of cannabis users correlates

with protection against gray matter reduction in the right hippocampus.

CBD has also been observed to attenuate the deficits in prose recall

and visuo-spatial associative memory of those currently under the

influence of cannabis,

implying neuroprotective effects against heavy THC exposure.

Neurogenesis might play a role in its neuroprotective effects, but

further research is required.

Regulation

Summary of the signalling pathways in the neural stem cell microenvironment.

Many factors may affect the rate of hippocampal neurogenesis. Exercise and an enriched environment

have been shown to promote the survival of neurons and the successful

integration of newborn cells into the existing hippocampus. Another factor is central nervous system injury since neurogenesis occurs after cerebral ischemia, epileptic seizures, and bacterial meningitis. On the other hand, conditions such as chronic stress, viral infection. and aging can result in a decreased neuronal proliferation.

Circulating factors within the blood may reduce neurogenesis. In healthy

aging humans, the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid levels of certain

chemokines are elevated. In a mouse model, plasma levels of these

chemokines correlate with reduced neurogenesis, suggesting that

neurogenesis may be modulated by certain global age-dependent systemic

changes. These chemokines include CCL11, CCL2 and CCL12, which are highly localized on mouse and human chromosomes, implicating a genetic locus in aging.

Another study implicated the cytokine, IL-1beta, which is produced by

glia. That study found that blocking IL-1 could partially prevent the

severe impairment of neurogenesis caused by a viral infection.

Epigenetic regulation

also plays a large role in neurogenesis. DNA methylation is critical in

the fate-determination of adult neural stem cells in the subventricular zone for post-natal neurogenesis through the regulation of neuronic genes such as Dlx2, Neurog2, and Sp8. Many microRNAs such as miR-124 and miR-9 have been shown to influence cortical size and layering during development.

History

Early neuroanatomists, including Santiago Ramón y Cajal, considered the nervous system fixed and incapable of regeneration. The first evidence of adult mammalian neurogenesis in the cerebral cortex was presented by Joseph Altman in 1962, followed by a demonstration of adult neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in 1963. In 1969, Joseph Altman discovered and named the rostral migratory stream as the source of adult generated granule cell neurons in the olfactory bulb.

Up until the 1980s, the scientific community ignored these findings

despite use of the most direct method of demonstrating cell

proliferation in the early studies, i.e. 3H-thymidine autoradiography.

By that time, Shirley Bayer (and Michael Kaplan) again showed that adult neurogenesis exists in mammals (rats), and Nottebohm showed the same phenomenon in birds sparking renewed interest in the topic. Studies in the 1990s

finally put research on adult neurogenesis into a mainstream pursuit.

Also in the early 1990s hippocampal neurogenesis was demonstrated in

non-human primates and humans. More recently, neurogenesis in the cerebellum of adult rabbits has also been characterized. Further, some authors (particularly Elizabeth Gould)

have suggested that adult neurogenesis may also occur in regions within

the brain not generally associated with neurogenesis including the neocortex. However, others have questioned the scientific evidence of these findings, arguing that the new cells may be of glial origin. Recent research has elucidated the regulatory effect of GABA

on neural stem cells. GABA's well-known inhibitory effects across the

brain also affect the local circuitry that triggers a stem cell to

become dormant. They found that diazepam (Valium) has a similar effect.