| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Population | 1.307 billion (16%; 2019) |

| GDP | $2.19 trillion (Nominal; 2017) $6.36 trillion (PPP; 2017) |

GDP growth

| 3.7% |

GDP per capita

| $1,720 (2017; 6th) |

| 140,000 (0.011%) | |

| Unemployment | 15% |

| Most numbers are from the International Monetary Fund. All values, unless otherwise stated, are in US dollars. | |

The economy of Africa consists of the trade, industry, agriculture, and human resources of the continent. As of 2012, approximately 1.3 billion people were living in 54 different countries in Africa. Africa is a resource-rich continent. Recent growth has been due to growth in sales in commodities, services, and manufacturing. West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa and Southern Africa in particular, are expected to reach a combined GDP of $29 trillion by 2050.

In March 2013, Africa was identified as the world's poorest inhabited continent: Africa's entire combined GDP is barely a third of the United States' GDP; however, the World Bank expects that most African countries will reach "middle income" status (defined as at least US$1,000 per person a year) by 2025 if current growth rates continue. In 2013, Africa was the world’s fastest-growing continent at 5.6% a year, and GDP is expected to rise by an average of over 6% a year between 2013 and 2023. In 2017, the African Development Bank reported Africa to be the world’s second-fastest growing economy, and estimates that average growth will rebound to 3.4% in 2017, while growth is expected to increase by 4.3% in 2018.

Growth has been present throughout the continent, with over one-third of African countries posting 6% or higher growth rates, and another 40% growing between 4% to 6% per year. Several international business observers have also named Africa as the future economic growth engine of the world.

History

Ancient Egyptian units of measurement also served as units of currency.

Africa's economy was diverse, driven by extensive trade routes that

developed between cities and kingdoms. Some trade routes were overland,

some involved navigating rivers, still others developed around port

cities. Large African empires became wealthy due to their trade

networks, for example Ancient Egypt, Nubia, Mali, Ashanti, and the Oyo Empire.

The Sultanate of Mogadishu's medieval currency.

Some parts of Africa had close trade relationships with Arab kingdoms, and by the time of the Ottoman Empire, Africans had begun converting to Islam in large numbers. This development, along with the economic potential in finding a trade route to the Indian Ocean,

brought the Portuguese to sub-Saharan Africa as an imperial force.

Colonial interests created new industries to feed European appetites for

goods such as palm oil, rubber, cotton, precious metals, spices, cash

crops other goods, and integrated especially the coastal areas with the

Atlantic economy.

Following the independence of African countries during the 20th

century, economic, political and social upheaval consumed much of the

continent. An economic rebound among some countries has been evident in

recent years, however.

The dawn of the African economic boom (which is in place since the 2000s) has been compared to the Chinese economic boom that had emerged in Asia since late 1970's. In 2013, Africa was home to seven of the world's fastest-growing economies.

As of 2018, Nigeria is the biggest economy in terms of nominal GDP, followed by South Africa; in terms of PPP, Egypt is second biggest after Nigeria.. Equatorial Guinea possessed Africa's highest GDP per capita albeit allegations of human rights violations. Oil-rich countries such as Algeria, Libya and Gabon, and mineral-rich Botswana emerged among the top economies since the 21st century, while Zimbabwe and the Democratic Republic of Congo,

potentially among the world's richest nations, have sunk into the list

of the world's poorest nations due to pervasive political corruption,

warfare and braindrain of workforce. Botswana remains the site of Africa's longest and one of the world's longest periods of economic boom (1966–1999).

Current conditions

The United Nations predicts Africa’s economic growth will reach 3.5% in 2018 and 3.7% in 2019.

As of 2007, growth in Africa had surpassed that of East Asia. Data

suggest parts of the continent are now experiencing fast growth, thanks

to their resources and increasing political stability and 'has steadily increased levels of peacefulness since 2007'. The World Bank reports the economy of Sub-Saharan African countries grew at rates that match or surpass global rates. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, the improvement in the region’s aggregate growth is largely attributable to a recovery in Egypt, Nigeria and South Africa, three of Africa’s largest economies.

The economies of the fastest growing African nations experienced

growth significantly above the global average rates. The top nations in

2007 include Mauritania with growth at 19.8%, Angola at 17.6%, Sudan at 9.6%, Mozambique at 7.9% and Malawi at 7.8%. Other fast growers include Rwanda, Mozambique, Chad, Niger, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia. Nonetheless, growth has been dismal, negative or sluggish in many parts of Africa including Zimbabwe, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo and Burundi. Many international agencies are increasingly interested in investing in emerging African economies. especially as Africa continues to maintain high economic growth despite current global economic recession.

The rate of return on investment in Africa is currently the highest in the developing world.

Debt relief is being addressed by some international institutions

in the interests of supporting economic development in Africa. In 1996,

the UN sponsored the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative, subsequently taken up by the IMF, World Bank and the African Development Fund (AfDF) in the form of the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). As of 2013, the initiative has given partial debt relief to 30 African countries.

Trade growth

Trade

has driven much of the growth in Africa's economy in the early 21st

century. China and India are increasingly important trade partners;

12.5% of Africa's exports are to China, and 4% are to India, which

accounts for 5% of China's imports and 8% of India's. The Group of Five

(Indonesia, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Thailand, and the United Arab

Emirates) are another increasingly important market for Africa's

exports.

Future

A mobile phone advertisement on the side of a van, Kampala, Uganda.

Africa's economy—with expanding trade, English language skills

(official in many Sub-Saharan countries), improving literacy and

education, availability of splendid resources and cheaper labour

force—is expected to continue to perform better into the future. Trade

between Africa and China stood at US$166 billion in 2011.

Africa will only experience a "demographic dividend" by 2035,

when its young and growing labour force will have fewer children and

retired people as dependents as a proportion of the population, making

it more demographically comparable to the US and Europe.

It is becoming a more educated labour force, with nearly half expected

to have some secondary-level education by 2020. A consumer class is also

emerging in Africa and is expected to keep booming. Africa has around

90 million people with household incomes exceeding $5,000, meaning that

they can direct more than half of their income towards discretionary

spending rather than necessities. This number could reach a projected

128 million by 2020.

During the President of the United States Barack Obama's visit to Africa in July 2013, he announced a US$7

billion plan to further develop infrastructure and work more

intensively with African heads of state. A new program named Trade

Africa, designed to boost trade within the continent as well as between

Africa and the U.S., was also unveiled by Obama.

Causes of the economic underdevelopment over the years

The seemingly intractable nature of Africa's poverty has led to debate concerning its root causes. Endemic warfare and unrest, widespread corruption, and despotic regimes are both causes and effects of the continued economic problems. The decolonization of Africa was fraught with instability aggravated by cold war conflict. Since the mid-20th century, the Cold War and increased corruption and despotism have also contributed to Africa's poor economy.

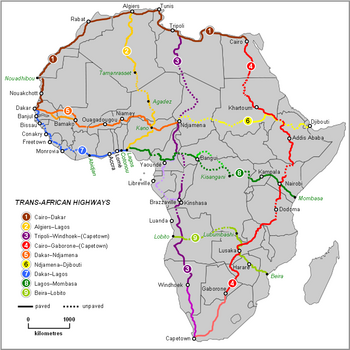

Infrastructure

According to the researchers at the Overseas Development Institute, the lack of infrastructure in many developing countries represents one of the most significant limitations to economic growth and achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Infrastructure investments and maintenance can be very expensive,

especially in such areas as landlocked, rural and sparsely populated

countries in Africa.

It has been argued that infrastructure investments contributed to

more than half of Africa's improved growth performance between 1990 and

2005 and increased investment is necessary to maintain growth and

tackle poverty. The returns to investment in infrastructure are very significant, with on average 30–40% returns for telecommunications (ICT) investments, over 40% for electricity generation, and 80% for roads.

In Africa, it is argued that to meet the MDGs by 2015,

infrastructure investments would need to reach about 15% of GDP (around

$93 billion a year). Currently, the source of financing varies significantly across sectors. Some sectors are dominated by state spending, others by overseas development aid (ODA) and yet others by private investors. In sub-Saharan Africa, the state spends around $9.4 billion out of a total of $24.9 billion.

In irrigation, SSA states represent almost all spending; in transport and energy a majority of investment is state spending; in Information and communication technologies and water supply and sanitation, the private sector represents the majority of capital expenditure. Overall, aid, the private sector and non-OECD financiers between them exceed state spending.

The private sector spending alone equals state capital expenditure,

though the majority is focused on ICT infrastructure investments. External financing increased from $7 billion (2002) to $27 billion (2009). China, in particular, has emerged as an important investor.

Colonialism

Railway map of Africa, including tracks proposed and under construction, The Statesman's Yearbook, 1899.

The economic impact of the colonization of Africa has been debated.

In this matter, the opinions are biased between

researchers, some of them consider that Europeans had a positive impact

on Africa; others affirm that Africa's development was slowed down by

colonial rule.

The principal aim of colonial rule in Africa by European colonial

powers was to exploit natural wealth in the African continent at a low

cost. Some writers, such as Walter Rodney in his book How Europe Underdeveloped Africa,

argue that these colonial policies are directly responsible for many of

Africa's modern problems. Critics of colonialism charge colonial rule

with injuring African pride, self-worth and belief in themselves. Other

post-colonial scholars, most notably Frantz Fanon

continuing along this line, have argued that the true effects of

colonialism are psychological and that domination by a foreign power

creates a lasting sense of inferiority and subjugation that creates a

barrier to growth and innovation. Such arguments posit that a new

generation of Africans free of colonial thought and mindset is emerging

and that this is driving economic transformation.

Historians L. H. Gann and Peter Duignan have argued that Africa

probably benefited from colonialism on balance. Although it had its

faults, colonialism was probably "one of the most efficacious engines

for cultural diffusion in world history".

These views, however, are controversial and are rejected by some who,

on balance, see colonialism as bad. The economic historian David Kenneth Fieldhouse

has taken a kind of middle position, arguing that the effects of

colonialism were actually limited and their main weakness wasn't in

deliberate underdevelopment but in what it failed to do. Niall Ferguson agrees with his last point, arguing that colonialism's main weaknesses were sins of omission.

Analysis of the economies of African states finds that independent

states such as Liberia and Ethiopia did not have better economic

performance than their post-colonial counterparts. In particular the

economic performance of former British colonies was better than both

independent states and former French colonies.

Africa's relative poverty predates colonialism. Jared Diamond argues in Guns, Germs, and Steel

that Africa has always been poor due to a number of ecological factors

affecting historical development. These factors include low population

density, lack of domesticated livestock and plants and the North-South

orientation of Africa's geography. However Diamond's theories have been criticized by some including James Morris Blaut as a form of environmental determinism. Historian John K. Thornton argues that sub-Saharan Africa was relatively wealthy and technologically advanced until at least the seventeenth century.

Some scholars who believe that Africa was generally poorer than the

rest of the world throughout its history make exceptions for certain

parts of Africa. Acemoglue and Robinson, for example, argue that most of

Africa has always been relatively poor, but "Aksum, Ghana, Songhay,

Mali, [and] Great Zimbabwe... were probably as developed as their

contemporaries anywhere in the world." A number of people including Rodney and Joseph E. Inikori

have argued that the poverty of Africa at the onset of the colonial

period was principally due to the demographic loss associated with the slave trade as well as other related societal shifts. Others such as J. D. Fage and David Eltis have rejected this view.

Language diversity

A randomly selected pair of people in Ghana has only an 8.1% chance of sharing a mother tongue.

African countries suffer from communication difficulties caused by language diversity. Greenberg's diversity index is the chance that two randomly selected people would have different mother tongues. Out of the most diverse 25 countries according to this index, 18 (72%) are African.

This includes 12 countries for which Greenberg's diversity index

exceeds 0.9, meaning that a pair of randomly selected people will have

less than 10% chance of having the same mother tongue. However, the

primary language of government, political debate, academic discourse,

and administration is often the language of the former colonial powers; English, French, or Portuguese.

Trade based theories

Dependency theory asserts that the wealth and prosperity of the superpowers and their allies in Europe, North America and East Asia

is dependent upon the poverty of the rest of the world, including

Africa. Economists who subscribe to this theory believe that poorer

regions must break their trading ties with the developed world in order

to prosper.

Less radical theories suggest that economic protectionism

in developed countries hampers Africa's growth. When developing

countries have harvested agricultural produce at low cost, they

generally do not export as much as would be expected. Abundant farm subsidies and high import tariffs in the developed world, most notably those set by Japan, the European Union's Common Agricultural Policy, and the United States Department of Agriculture, are thought to be the cause. Although these subsidies and tariffs have been gradually reduced, they remain high.

Local conditions also affect exports; state over-regulation in

several African nations can prevent their own exports from becoming

competitive. Research in Public Choice economics such as that of Jane

Shaw suggest that protectionism operates in tandem with heavy State

intervention combining to depress economic development. Farmers subject

to import and export restrictions cater to localized markets, exposing

them to higher market volatility and fewer opportunities. When subject

to uncertain market conditions, farmers press for governmental

intervention to suppress competition in their markets, resulting in

competition being driven out of the market. As competition is driven out

of the market, farmers innovate less and grow less food further

undermining economic performance.

Governance

Although Africa and Asia had similar levels of income in the 1960s,

Asia has since outpaced Africa, with the exception of a few extremely

poor and war-torn countries like Afghanistan and Yemen. One school of economists argues that Asia's superior economic development lies in local investment. Corruption in Africa consists primarily of extracting economic rent and moving the resulting financial capital overseas instead of investing at home; the stereotype of African dictators with Swiss bank accounts is often accurate. University of Massachusetts Amherst researchers estimate that from 1970 to 1996, capital flight from 30 sub-Saharan countries totalled $187bn, exceeding those nations' external debts. This disparity in development is consistent with the model theorized by economist Mancur Olson.

Because governments were politically unstable and new governments often

confiscated their predecessors' assets, officials would stash their

wealth abroad, out of reach of any future expropriation.

Socialist governments influenced by Marxism, and the land reform they have enacted, have also contributed to economic stagnation in Africa. For example, the regime of Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe,

particularly the land seizures from white farmers, led to the collapse

of the country's agricultural economy, which had formerly been one of

Africa's strongest; Mugabe had been previously supported by the USSR during the Rhodesian Bush War. In Tanzania, socialist President Julius Nyerere resigned in 1985 after his policies of agricultural collectivisation in 1971 led to economic collapse, with famine only being averted by generous aid from the IMF and other foreign entities. Tanzania was left as one of the world's poorest and most aid-dependent nations, and has taken decades to recover. Since the abolition of the socialist one-party state in 1992 and the transition to democracy, Tanzania has experienced rapid economic growth, with growth of 6.5% in 2017.

Foreign aid

Food shipments in case of dire local shortage are generally uncontroversial; but as Amartya Sen

has shown, most famines involve a local lack of income rather than of

food. In such situations, food aid—as opposed to financial aid—has the

effect of destroying local agriculture and serves mainly to benefit

Western agribusiness which are vastly overproducing food as a result of agricultural subsidies.

Historically, food aid is more highly correlated with excess

supply in Western countries than with the needs of developing countries.

Foreign aid has been an integral part of African economic development

since the 1980s.

The aid model has been criticized for supplanting trade initiatives. Growing evidence shows that foreign aid has made the continent poorer.

One of the biggest critics of the aid development model is economist

Dambiso Moyo (a Zambian economist based in the US), who introduced the Dead Aid model, which highlights how foreign aid has been a deterrent for local development.

Today, Africa faces the problem of attracting foreign aid in

areas where there is potential for high income from demand. It is in

need of more economic policies and active participation in the world

economy. As globalization has heightened the competition for foreign aid

among developing countries, Africa has been trying to improve its

struggle to receive foreign aid by taking more responsibility at the

regional and international level. In addition, Africa has created the

‘Africa Action Plan’ in order to obtain new relationships with

development partners to share responsibilities regarding discovering

ways to receive aid from foreign investors.

Trade blocks and multilateral organizations

The African Union is the largest international economic grouping on the continent. The confederation's goals include the creation of a free trade area, a customs union, a single market, a central bank, and a common currency (see African Monetary Union), thereby establishing economic and monetary union. The current plan is to establish an African Economic Community with a single currency by 2023. The African Investment Bank is meant to stimulate development. The AU plans also include a transitional African Monetary Fund leading to an African Central Bank. Some parties support development of an even more unified United States of Africa.

International monetary and banking unions include:

Major economic unions are shown in the chart below.

| African Economic Community | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillars regional blocs (REC)1 |

Area (km²) | Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| in millions | per capita | ||||

| AEC | 29,910,442 | 853,520,010 | 2,053,706 | 2,406 | 54 |

| ECOWAS | 5,112,903 | 349,154,000 | 1,322,452 | 3,888 | 15 |

| ECCAS | 6,667,421 | 121,245,958 | 175,928 | 1,451 | 11 |

| SADC | 9,882,959 | 233,944,179 | 737,335 | 3,152 | 15 |

| EAC | 2,440,409 | 169,519,847 | 411,813 | 2,429 | 6 |

| COMESA | 12,873,957 | 406,102,471 | 735,599 | 1,811 | 20 |

| IGAD | 5,233,604 | 187,969,775 | 225,049 | 1,197 | 7 |

| Other African blocs |

Area (km²) | Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| in millions | per capita | ||||

| CEMAC 2 | 3,020,142 | 34,970,529 | 85,136 | 2,435 | 6 |

| SACU | 2,693,418 | 51,055,878 | 541,433 | 10,605 | 5 |

| UEMOA 1 | 3,505,375 | 80,865,222 | 101,640 | 1,257 | 8 |

| UMA 2 | 5,782,140 | 84,185,073 | 491,276 | 5,836 | 5 |

| GAFTA 3 | 5,876,960 | 166,259,603 | 635,450 | 3,822 | 5 |

| 1 Economic bloc inside a pillar REC

2 Proposed for pillar REC, but objecting participation

3 Non-African members of GAFTA are excluded from figures

smallest value among the blocs compared

largest value among the blocs compared

During 2004. Source: CIA World Factbook 2005, IMF WEO Database

| |||||

Economic variants and indicators

Map of Africa by nominal GDP in billions USD (2008).

200+

100–200

50–100

20–50

10–20

5–10

1–5

0–1

After an initial rebound from the 2009 world economic crisis,

Africa’s economy was undermined in the year 2011 by the Arab uprisings.

The continent’s growth fell back from 5% in 2010 to 3.4% in 2011. With

the recovery of North African economies and sustained improvement in

other regions, growth across the continent is expected to accelerate to

4.5% in 2012 and 4.8% in 2013. Short-term problems for the world economy

remain as Europe confronts its debt crisis. Commodity prices—crucial

for Africa—have declined from their peak due to weaker demand and

increased supply, and some could fall further. But prices are expected

to remain at levels favourable for African exporter.

Regions

Economic

activity has rebounded across Africa. However, the pace of recovery was

uneven among groups of countries and subregions. Oil-exporting

countries generally expanded more strongly than oil-importing countries.

West Africa and East Africa were the two best-performing subregions in

2010.

Intra-African trade has been slowed by protectionist policies

among countries and regions. Despite this, trade between countries

belonging to the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), a particularly strong economic region, grew six-fold over the past decade up to 2012.

Ghana and Kenya, for example, have developed markets within the region

for construction materials, machinery, and finished products, quite

different from the mining and agriculture products that make up the bulk

of their international exports.

The African Ministers of Trade agreed in 2010 to create a

Pan-Africa Free Trade Zone. This would reduce countries' tariffs on

imports and increase intra-African trade, and it is hoped, the

diversification of the economy overall.

Economic sectors and industries

Because

Africa’s export portfolio remains predominantly based on raw material,

its export earnings are contingent on commodity price fluctuations. This

exacerbates the continent’s susceptibility to external shocks and

bolsters the need for export diversification. Trade in services, mainly

travel and tourism, continued to rise in year 2012, underscoring the

continent’s strong potential in this sphere.

Agriculture

A Kenyan farmer at work in the Mount Kenya region

The situation whereby African nations export crops to the West while

millions on the continent starve has been blamed on developed countries

including Japan, the European Union and the United States. These countries protect their own agricultural sectors with high import tariffs and offer subsidies to their farmers, which many contend leads the overproduction

of such commodities as grain, cotton and milk. The result of this is

that the global price of such products is continually reduced until

Africans are unable to compete, except for cash crops that do not grow

easily in a northern climate.

In recent years countries such as Brazil, which has experienced

progress in agricultural production, have agreed to share technology

with Africa to increase agricultural production in the continent to make

it a more viable trade partner. Increased investment in African agricultural technology in general has the potential to reduce poverty in Africa. The demand market for African cocoa has experienced a price boom in 2008. The Nigerian, South African and Ugandan governments have targeted policies to take advantage of the increased demand for certain agricultural products and plan to stimulate agricultural sectors. The African Union has plans to heavily invest in African agriculture and the situation is closely monitored by the UN.

Energy

Mean Wind Speed in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Global Horizontal Irradiation in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Africa has significant resources for generating energy in several

forms (hydroelectric, reserves of petroleum and gas, coal production,

uranium production, renewable energy such as solar, wind and

geothermal). The lack of development and infrastructure means that

little of this potential is actually in use today.

The largest consumers of electric power in Africa are South Africa,

Libya, Namibia, Egypt, Tunisia, and Zimbabwe, which each consume between

1000 and 5000 KWh/m2 per person, in contrast with African

states such as Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Tanzania, where electricity

consumption per person is negligible.

Petroleum and petroleum products are the main export of 14

African countries. Petroleum and petroleum products accounted for a

46.6% share of Africa's total exports in 2010; the second largest export

of Africa as a whole is natural gas, in its gaseous state and as

liquified natural gas, accounting for a 6.3% share of Africa's exports.

Infrastructure

Lagos, Nigeria, Africa's largest city

Lack of infrastructure creates barriers for African businesses.

Although it has many ports, a lack of supporting transportation

infrastructure adds 30–40% to costs, in contrast to Asian ports.

Many large infrastructure projects are underway across Africa. By far,

most of these projects are in the production and transportation of

electric power. Many other projects include paved highways, railways,

airports, and other construction.

Telecommunications infrastructure is also a growth area in

Africa. Although Internet penetration lags other continents, it has

still reached 9%. As of 2011, it was estimated that 500,000,000 mobile

phones of all types were in use in Africa, including 15,000,000 "smart phones".

Mining and drilling

The mineral industry of Africa is one of the largest mineral

industries in the world. Africa is the second biggest continent, with 30

million km² of land, which implies large quantities of resources.

For many African countries, mineral exploration and production

constitute significant parts of their economies and remain keys to

future economic growth. Africa is richly endowed with mineral reserves

and ranks first or second in quantity of world reserves of bauxite,

cobalt, industrial diamond, phosphate rock, platinum-group metals (PGM),

vermiculite, and zirconium. Gold mining is Africa's main mining

resource.

African mineral reserves rank first or second for bauxite,

cobalt, diamonds, phosphate rocks, platinum-group metals (PGM),

vermiculite, and zirconium. Many other minerals are also present in

quantity. The 2005 share of world production from African soil is the

following: bauxite 9%; aluminium 5%; chromite 44%; cobalt 57%; copper

5%; gold 21%; iron ore 4%; steel 2%; lead (Pb) 3%; manganese 39%; zinc

2%; cement 4%; natural diamond 46%; graphite 2%; phosphate rock 31%;

coal 5%; mineral fuels (including coal) & petroleum 13%; uranium

16%.

Manufacturing

Both the African Union and the United Nations

have outlined plans in modern years on how Africa can help itself

industrialize and develop significant manufacturing sectors to levels

proportional to the African economy in the 1960s with 21st-century

technology. This focus on growth and diversification of manufacturing and industrial production, as well as diversification

of agricultural production, has fueled hopes that the 21st century will

prove to be a century of economic and technological growth for Africa.

This hope, coupled with the rise of new leaders in Africa in the future,

inspired the term "the African Century",

referring to the 21st century potentially being the century when

Africa's vast untapped labor, capital, and resource potentials might

become a world player.

This hope in manufacturing and industry is helped by the boom in communications technology and local mining industry in much of sub-Saharan Africa. Namibia has attracted industrial investments in recent years and South Africa has begun offering tax incentives to attract foreign direct investment projects in manufacturing.

Countries such as Mauritius have plans for developing new "green technology" for manufacturing.

Developments such as this have huge potential to open new markets for

African countries as the demand for alternative "green" and clean

technology is predicted to soar in the future as global oil reserves dry

up and fossil fuel-based technology becomes less economically viable.

Nigeria in recent years has been embracing industrialization, It currently has an indigenous vehicle manufacturing company, Innoson Vehicle Manufacturing (IVM) which manufactures Rapid Transit Buses, Trucks and SUVs with an upcoming introduction of Cars. Their various brands of vehicle are currently available in Nigeria, Ghana and other West African Nations.

Nigeria also has few Electronic manufacturers like Zinox, the first

Branded Nigerian Computer and Electronic gadgets (like tablet PCs)

manufacturers.

In 2013, Nigeria introduced a policy regarding import duty on vehicles

to encourage local manufacturing companies in the country. In this regard, some foreign vehicle manufacturing companies like Nissan have made known their plans to have manufacturing plants in Nigeria.

Apart from Electronics and vehicles, most consumer, pharmaceutical and

cosmetic products, building materials, textiles, home tools, plastics

and so on are also manufactured in the country and exported to other

west African and African countries. Nigeria is currently the largest manufacturer of cement in Sub-saharan Africa. and Dangote Cement Factory, Obajana is the largest cement factory in sub-saharan Africa. Ogun

is considered to be Nigeria's industrial hub (as most factories are

located in Ogun and even more companies are moving there), followed by Lagos.

The manufacturing sector is small but growing in East Africa. The main industries are textile and clothing, leather processing, agribusiness, chemical products, electronics and vehicles. East African countries like Uganda also produce motorcycles for the domestic market.

Investment and banking

Many financial firms have offices in downtown Johannesburg, South Africa.

Africa's US$107 billion financial services industry will log impressive growth for the rest of the decade as more banks target the continent's emerging middle class. The banking sector has been experiencing record growth, among others due to various technological innovations.

China and India

have showed increasing interest in emerging African economies in the

21st century. Reciprocal investment between Africa and China increased

dramatically in recent years amidst the current world financial crisis.

The increased investment in Africa by China has attracted the

attention of the European Union and has provoked talks of competitive

investment by the EU. Members of the African diaspora

abroad, especially in the EU and the United States, have increased

efforts to use their businesses to invest in Africa and encourage

African investment abroad in the European economy.

Remittances from the African diaspora and rising interest in

investment from the West will be especially helpful for Africa's least

developed and most devastated economies, such as Burundi, Togo and

Comoros.

However, experts lament the high fees involved in sending remittances

to Africa due to a duopoly of Western Union and MoneyGram that is

controlling Africa’s remittance market, making Africa is the most

expensive cash transfer market in the world.

According to some experts, the high processing fees involved in sending

money to Africa are hampering African countries’ development.

Angola has announced interests in investing in the EU, Portugal in particular.

South Africa has attracted increasing attention from the United States

as a new frontier of investment in manufacture, financial markets and

small business, as has Liberia in recent years under their new leadership.

There are two African currency unions:

the West African Banque Centrale des États de l'Afrique de l'Ouest

(BCEAO) and the Central African Banque des États de l'Afrique Centrale

(BEAC). Both use the CFA franc

as their legal tender. The idea of a single currency union across

Africa has been floated, and plans exist to have it established by 2020,

though many issues, such as bringing continental inflation rates below 5

percent, remain hurdles in its finalization.

Stock exchanges

The Bourse de Tunis headquarters in Tunis, Tunisia

As of 2012, Africa has 23 stock exchanges,

twice as many as it had 20 years earlier. Nonetheless, African stock

exchanges still account for less than 1% of the world's stock exchange

activity. The top ten stock exchanges in Africa by stock capital are (amounts are given in billions of United States dollars):

- South Africa (82.88)(2014)

- Egypt ($73.04 billion (30 November 2014 est.))

- Morocco (5.18)

- Nigeria (5.11) (Actually has a market capitalisation value of $39.27Bln)

- Kenya (1.33)

- Tunisia (0.88)

- BRVM (regional stock exchange whose members include Benin, Burkina Faso, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Mali, Niger, Senegal and Togo: 6.6)

- Mauritius (0.55)

- Botswana (0.43)

- Ghana (.38)

Between 2009 and 2012, a total of 72 companies were launched on the stock exchanges of 13 African countries.

Trade blocs and multilateral organizations

The African Union is the largest international economic grouping on the continent. The confederation's goals include the creation of a free trade area, a customs union, a single market, a central bank, and a common currency (see African Monetary Union), thereby establishing economic and monetary union. The current plan is to establish an African Economic Community with a single currency by 2023. The African Investment Bank is meant to stimulate development. The AU plans also include a transitional African Monetary Fund leading to an African Central Bank. Some parties support development of an even more unified United States of Africa.

International monetary and banking unions include:

Major economic unions are shown in the chart below.

| African Economic Community | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillars regional blocs (REC)1 |

Area (km²) | Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| in millions | per capita | ||||

| AEC | 29,910,442 | 853,520,010 | 2,053,706 | 2,406 | 54 |

| ECOWAS | 5,112,903 | 349,154,000 | 1,322,452 | 3,888 | 15 |

| ECCAS | 6,667,421 | 121,245,958 | 175,928 | 1,451 | 11 |

| SADC | 9,882,959 | 233,944,179 | 737,335 | 3,152 | 15 |

| EAC | 2,440,409 | 169,519,847 | 411,813 | 2,429 | 6 |

| COMESA | 12,873,957 | 406,102,471 | 735,599 | 1,811 | 20 |

| IGAD | 5,233,604 | 187,969,775 | 225,049 | 1,197 | 7 |

| Other African blocs |

Area (km²) | Population | GDP (PPP) ($US) | Member states | |

| in millions | per capita | ||||

| CEMAC 2 | 3,020,142 | 34,970,529 | 85,136 | 2,435 | 6 |

| SACU | 2,693,418 | 51,055,878 | 541,433 | 10,605 | 5 |

| UEMOA 1 | 3,505,375 | 80,865,222 | 101,640 | 1,257 | 8 |

| UMA 2 | 5,782,140 | 84,185,073 | 491,276 | 5,836 | 5 |

| GAFTA 3 | 5,876,960 | 166,259,603 | 635,450 | 3,822 | 5 |

| 1 Economic bloc inside a pillar REC

2 Proposed for pillar REC, but objecting participation

3 Non-African members of GAFTA are excluded from figures

smallest value among the blocs compared

largest value among the blocs compared

During 2004. Source: CIA World Factbook 2005, IMF WEO Database

| |||||

Regional economic organizations

During the 1960s, Ghanaian politician Kwame Nkrumah promoted economic and political union of African countries, with the goal of independence.

Since then, objectives, and organizations, have multiplied. Recent

decades have brought efforts at various degrees of regional economic

integration. Trade between African states accounts for only 11% of

Africa's total commerce as of 2012, around five times less than in Asia.

Most of this intra-Africa trade originates from South Africa and most

of the trade exports coming out of South Africa goes to abutting

countries in Southern Africa.