| |

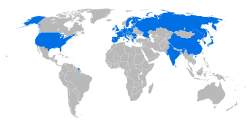

Thirty-five participating nations

| |

| Formation | 24 October 2007 |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Saint-Paul-lès-Durance, France |

Director-General

| Bernard Bigot |

| Website | www |

| |

| Type | Tokamak |

|---|---|

| Construction date | 2013–2025 |

| Major radius | 6.2 m |

| Plasma volume | 840 m3 |

| Magnetic field | 11.8 T (peak toroidal field on coil) 5.3 T (toroidal field on axis) 6 T (peak poloidal field on coil) |

| Heating | 50 MW |

| Fusion power | 500 MW |

| Continuous operation | up to 1000 s |

| Location | Saint-Paul- lès-Durance, France |

ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) is an international nuclear fusion research and engineering megaproject, which will be the world's largest magnetic confinement plasma physics experiment. It is an experimental tokamak nuclear fusion reactor that is being built next to the Cadarache facility in Saint-Paul-lès-Durance, in Provence, southern France.

ITER was proposed in 1987 and designed as the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, according to the "ITER Technical Basis," published by the International Atomic Energy Agency, in 2002. By 2005, the ITER organization abandoned the original meaning of the acronym iter, and instead adopted a new meaning, the Latin word for "the way."

The ITER thermonuclear fusion reactor has been designed to produce a fusion plasma equivalent to 500 megawatts (MW) of thermal output power for around twenty minutes while 50 megawatts of thermal power are injected into the tokamak, resulting in a ten-fold gain of plasma heating power. Thereby the machine aims to demonstrate the principle of producing more thermal power from the fusion process than is used to heat the plasma, something that has not yet been achieved in any fusion reactor. The total electricity consumed by the reactor and facilities will range from 110 MW up to 620 MW peak for 30-second periods during plasma operation. Thermal-to-electric conversion is not included in the design because ITER will not produce sufficient power for net electrical production. The emitted heat from the fusion reaction will be vented to the atmosphere.

The project is funded and run by seven member entities—the European Union, India, Japan, China, Russia, South Korea, and the United States. The EU, as host party for the ITER complex, is contributing about 45 percent of the cost, with the other six parties contributing approximately 9 percent each. In 2016 the ITER organization signed a technical cooperation agreement with the national nuclear fusion agency of Australia, enabling this country access to research results of ITER in exchange for construction of selected parts of the ITER machine.

Construction of the ITER Tokamak complex started in 2013 and the building costs are now over US$14 billion as of June 2015. The facility is expected to finish its construction phase in 2025 and will start commissioning the reactor that same year. Initial plasma experiments are scheduled to begin in 2025, with full deuterium–tritium fusion experiments starting in 2035. If ITER becomes operational, it will become the largest magnetic confinement plasma physics experiment in use with a plasma volume of 840 cubic meters, surpassing the Joint European Torus by almost a factor of 10.

The goal of ITER is to demonstrate the scientific and technological feasibility of fusion energy for peaceful use. It is the latest and largest of more than 100 fusion reactors built since the 1950s. ITER's planned successor, DEMO, is expected to be the first fusion reactor to produce electricity in an experimental environment. DEMO's anticipated success is expected to lead to full-scale electricity-producing fusion power stations and future commercial reactors.

Background

ITER will produce energy by fusing deuterium and tritium to helium.

Fusion power has the potential to provide sufficient energy to

satisfy mounting demand, and to do so sustainably, with a relatively

small impact on the environment.

Nuclear fusion has many potential attractions. Firstly, its hydrogen isotope fuels are relatively abundant – one of the necessary isotopes, deuterium, can be extracted from seawater, while the other fuel, tritium, would be bred from a lithium blanket using neutrons produced in the fusion reaction itself. Furthermore, a fusion reactor would produce virtually no CO2 or atmospheric pollutants, and its radioactive waste products would mostly be very short-lived compared to those produced by conventional nuclear reactors.

On 21 November 2006, the seven participants formally agreed to fund the creation of a nuclear fusion reactor.

The program is anticipated to last for 30 years – 10 for construction,

and 20 of operation. ITER was originally expected to cost approximately

€5 billion, but the rising price of raw materials and changes to the

initial design have seen that amount almost triple to €13 billion. The reactor is expected to take 10 years to build with completion scheduled for 2019. Site preparation has begun in Cadarache, France, and procurement of large components has started.

When supplied with 300 MW of electrical power, ITER is expected to produce the equivalent of 500 MW of thermal power sustained for up to 1,000 seconds. This compares to JET's

consumption of 700 MW of electrical power and peak thermal output of 16

MW for less than a second) by the fusion of about 0.5 g of deuterium/tritium mixture in its approximately 840 m3

reactor chamber. The heat produced in ITER will not be used to generate

any electricity because after accounting for losses and the 300 MW

minimum power input, the

output will be equivalent to a zero (net) power reactor.

Organization history

Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev at the Geneva Summit in 1985

ITER began in 1985 as a Reagan–Gorbachev initiative with the equal participation of the Soviet Union, the European Atomic Energy Community, the United States, and Japan through the 1988–1998 initial design phases. Preparations for the first Gorbachev-Reagan Summit showed that there were no tangible agreements in the works for the summit.

One energy research project, however, was being considered quietly by two physicists, Alvin Trivelpiece and Evgeny Velikhov.

The project involved collaboration on the next phase of magnetic fusion

research — the construction of a demonstration model. At the time,

magnetic fusion research was ongoing in Japan, Europe, the Soviet Union

and the US. Velikhov and Trivelpiece believed that taking the next step

in fusion research would be beyond the budget of any of the key nations

and that collaboration would be useful internationally.

A major bureaucratic fight erupted in the US government over the

project. One argument against collaboration was that the Soviets would

use it to steal US technology and know-how. A second was symbolic — the

Soviet physicist Andrei Sakharov was in internal exile and the US was pushing the Soviet Union on its human rights record. The United States National Security Council convened a meeting under the direction of William Flynn Martin that resulted in a consensus that the US should go forward with the project.

Martin and Velikhov concluded the agreement that was agreed at

the summit and announced in the last paragraph of this historic summit

meeting, "... The two leaders emphasized the potential importance of the

work aimed at utilizing controlled thermonuclear fusion for peaceful

purposes and, in this connection, advocated the widest practicable

development of international cooperation in obtaining this source of

energy, which is essentially inexhaustible, for the benefit for all

mankind."

Conceptual and engineering design phases carried out under the auspices of the IAEA

led to an acceptable, detailed design in 2001, underpinned by US$650

million worth of research and development by the "ITER Parties" to

establish its practical feasibility. These parties, namely EU, Japan, Russian Federation

(replacing the Soviet Union), and United States (which opted out of the

project in 1999 and returned in 2003), were joined in negotiations by

China, South Korea, and Canada (who then terminated its participation at the end of 2003). India officially became part of ITER in December 2005.

On 28 June 2005, it was officially announced that ITER would be built in the European Union

in Southern France. The negotiations that led to the decision ended in a

compromise between the EU and Japan, in that Japan was promised 20% of

the research staff on the French location of ITER, as well as the head

of the administrative body of ITER. In addition, another research

facility for the project will be built in Japan, and the European Union

has agreed to contribute about 50% of the costs of this institution.

On 21 November 2006, an international consortium signed a formal agreement to build the reactor. On 24 September 2007, the People's Republic of China became the seventh party to deposit the ITER Agreement to the IAEA. Finally, on 24 October 2007, the ITER Agreement entered into force and the ITER Organization legally came into existence.

Objectives

ITER's mission is to demonstrate the feasibility of fusion power, and prove that it can work without negative impact. Specifically, the project aims to:

- Momentarily produce a fusion plasma with thermal power ten times greater than the injected thermal power (a Q value of 10).

- Produce a steady-state plasma with a Q value greater than 5. (Q = 1 is scientific breakeven.)

- Maintain a fusion pulse for up to 8 minutes.

- Develop technologies and processes needed for a fusion power station — including superconducting magnets and remote handling (maintenance by robot).

- Verify tritium breeding concepts.

- Refine neutron shield/heat conversion technology (most of the energy in the D+T fusion reaction is released in the form of fast neutrons).

Timeline and current status

Aerial view of the ITER site in 2018

ITER construction status in 2018

In 1978, the European Commission, Japan, United States, and USSR joined in the International Tokamak Reactor (INTOR) Workshop, under the auspices of the International Atomic Energy Agency

(IAEA), to assess the readiness of magnetic fusion to move forward to

the experimental power reactor (EPR) stage, to identify the additional R&D

that must be undertaken, and to define the characteristics of such an

EPR by means of a conceptual design. Hundreds of fusion scientists and

engineers in each participating country took part in a detailed

assessment of the then present status of the tokamak

confinement concept vis-a-vis the requirements of an EPR, identified

the required R&D by early 1980, and produced a conceptual design by

mid-1981.

In 1985, at the Geneva summit meeting in 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev suggested to Ronald Reagan

that the two countries jointly undertake the construction of a tokamak

EPR as proposed by the INTOR Workshop. The ITER project was initiated in

1988.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1988 | ITER project officially initiated. Conceptual design activities ran from 1988 to 1990. |

| 1992 | Engineering design activities from 1992 to 1998. |

| 2005 | India officially became part of ITER. |

| 2006 | Approval of a cost estimate of €10 billion (US$12.8 billion) projecting the start of construction in 2008 and completion a decade later. |

| 2008 | Site preparation start, ITER itinerary start. |

| 2009 | Site preparation completion. |

| 2010 | Tokamak complex excavation starts. |

| 2013 | Tokamak complex construction starts. |

| 2015 | Tokamak construction starts, but the schedule is extended by at least six years. |

| 2016 | The Atomic Energy Organization of Iran formally requests to join ITER. |

| 2017 | Assembly Hall ready for equipment |

| 2018-2025 | Assembly and integration |

| 2025 | Planned: Assembly ends; commissioning phase starts |

| 2025 | Planned: Achievement of first plasma. |

| 2035 | Planned: Start of deuterium–tritium operation. |

Reactor overview

When deuterium and tritium fuse, two nuclei come together to form a helium nucleus (an alpha particle), and a high-energy neutron.

- 2

1D

+ 3

1T

→ 4

2He

+ 1

0n

+ 17.59 MeV

While nearly all stable isotopes lighter on the periodic table than iron-56 and nickel-62, which have the highest binding energy per nucleon,

will fuse with some other isotope and release energy, deuterium and

tritium are by far the most attractive for energy generation as they

require the lowest activation energy (thus lowest temperature) to do so,

while producing among the most energy per unit weight.

All proto- and mid-life stars radiate enormous amounts of energy

generated by fusion processes. Mass for mass, the deuterium–tritium

fusion process releases roughly three times as much energy as

uranium-235 fission, and millions of times more energy than a chemical

reaction such as the burning of coal. It is the goal of a fusion power

station to harness this energy to produce electricity.

Activation energies for fusion reactions are generally high because the protons in each nucleus will tend to strongly repel one another, as they each have the same positive charge. A heuristic for estimating reaction rates is that nuclei must be able to get within 100 femtometers (1 × 10−13 meter) of each other, where the nuclei are increasingly likely to undergo quantum tunneling past the electrostatic barrier and the turning point where the strong nuclear force

and the electrostatic force are equally balanced, allowing them to

fuse. In ITER, this distance of approach is made possible by high

temperatures and magnetic confinement.

High temperatures give the nuclei enough energy to overcome their electrostatic repulsion (see Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution). For deuterium and tritium, the optimal reaction rates occur at temperatures on the order of 100,000,000 K. The plasma is heated to a high temperature by ohmic heating (running a current through the plasma). Additional heating is applied using neutral beam injection (which cross magnetic field lines without a net deflection and will not cause a large electromagnetic disruption) and radio frequency (RF) or microwave heating.

At such high temperatures, particles have a large kinetic energy,

and hence velocity. If unconfined, the particles will rapidly escape,

taking the energy with them, cooling the plasma to the point where net

energy is no longer produced. A successful reactor would need to contain

the particles in a small enough volume for a long enough time for much

of the plasma to fuse.

In ITER and many other magnetic confinement reactors, the plasma, a gas of charged particles, is confined using magnetic fields. A charged particle moving through a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to the direction of travel, resulting in centripetal acceleration, thereby confining it to move in a circle or helix around the lines of magnetic flux.

A solid confinement vessel is also needed, both to shield the

magnets and other equipment from high temperatures and energetic photons

and particles, and to maintain a near-vacuum for the plasma to

populate.

The containment vessel is subjected to a barrage of very energetic

particles, where electrons, ions, photons, alpha particles, and neutrons

constantly bombard it and degrade the structure. The material must be

designed to endure this environment so that a power station would be

economical. Tests of such materials will be carried out both at ITER and

at IFMIF (International Fusion Materials Irradiation Facility).

Once fusion has begun, high energy

neutrons will radiate from the reactive regions of the plasma, crossing

magnetic field lines easily due to charge neutrality (see neutron flux).

Since it is the neutrons that receive the majority of the energy, they

will be ITER's primary source of energy output. Ideally, alpha particles

will expend their energy in the plasma, further heating it.

Beyond the inner wall of the containment vessel one of several

test blanket modules will be placed. These are designed to slow and

absorb neutrons in a reliable and efficient manner, limiting damage to

the rest of the structure, and breeding tritium for fuel from

lithium-bearing ceramic pebbles contained within the blanket module

following the following reactions:

- 1

0n

+ 6

3Li

→ 3

1T

+ 4

2He - 1

0n

+ 7

3Li

→ 3

1T

+ 4

2He

+ 1

0n

where the reactant neutron is supplied by the D-T fusion reaction.

Energy absorbed from the fast neutrons is extracted and passed

into the primary coolant. This heat energy would then be used to power

an electricity-generating turbine in a real power station; in ITER this

generating system is not of scientific interest, so instead the heat

will be extracted and disposed of.

Technical design

Drawing of the ITER tokamak and integrated plant systems

Vacuum vessel

Cross-section of part of the planned ITER fusion reaction vessel.

The vacuum vessel is the central part of the ITER machine: a double

walled steel container in which the plasma is contained by means of

magnetic fields.

The ITER vacuum vessel will be twice as large and 16 times as

heavy as any previously manufactured fusion vessel: each of the nine torus shaped sectors will weigh between 390 and 430 tonnes.

When all the shielding and port structures are included, this adds up

to a total of 5,116 tonnes. Its external diameter will measure 19.4

metres (64 ft), the internal 6.5 metres (21 ft). Once assembled, the

whole structure will be 11.3 metres (37 ft) high.

The primary function of the vacuum vessel is to provide a

hermetically sealed plasma container. Its main components are the main

vessel, the port structures and the supporting system. The main vessel

is a double walled structure with poloidal and toroidal stiffening ribs

between 60-millimetre-thick (2.4 in) shells to reinforce the vessel

structure. These ribs also form the flow passages for the cooling water.

The space between the double walls will be filled with shield

structures made of stainless steel. The inner surfaces of the vessel

will act as the interface with breeder modules containing the breeder

blanket component. These modules will provide shielding from the

high-energy neutrons produced by the fusion reactions and some will also

be used for tritium breeding concepts.

The vacuum vessel has 18 upper, 17 equatorial and 9 lower ports

that will be used for remote handling operations, diagnostic systems,

neutral beam injections and vacuum pumping.

Breeder blanket

Owing to very limited terrestrial resources of tritium,

a key component of the ITER reactor design is the breeder blanket. This

component, located adjacent to the vacuum vessel, serves to produce

tritium through reaction with neutrons from the plasma. There are

several reactions that produce tritium within the blanket. 6Li

produces tritium via n,t reactions with moderated neutrons, 7Li

produces tritium via interactions with higher energy neutrons via n,nt reactions. Concepts for the breeder blanket include helium cooled lithium lead (HCLL) and helium cooled pebble bed (HCPB) methods. Six different Test Blanket Modules (TBM) will be tested in ITER and will share a common box geometry. Materials for use as breeder pebbles in the HCPB concept include lithium metatitanate and lithium orthosilicate. Requirements of breeder materials include good tritium production and extraction, mechanical stability and low activation levels.

produces tritium via n,t reactions with moderated neutrons, 7Li

produces tritium via interactions with higher energy neutrons via n,nt reactions. Concepts for the breeder blanket include helium cooled lithium lead (HCLL) and helium cooled pebble bed (HCPB) methods. Six different Test Blanket Modules (TBM) will be tested in ITER and will share a common box geometry. Materials for use as breeder pebbles in the HCPB concept include lithium metatitanate and lithium orthosilicate. Requirements of breeder materials include good tritium production and extraction, mechanical stability and low activation levels.

Magnet system

The central solenoid coil will use superconducting niobium-tin to carry 46 kA and produce a field of up to 13.5 teslas.

The 18 toroidal field coils will also use niobium-tin. At their maximum field strength of 11.8 teslas, they will be able to store 41 gigajoules. They have been tested at a record 80 kA. Other lower field ITER magnets (PF and CC) will use niobium-titanium

for their superconducting elements. As of now the in-wall shielding

blocks to protect the magnets from high energy neutrons are being

manufactured and transported from the Avasarala technologies in

Bangalore India to the ITER center.

Additional heating

There will be three types of external heating in ITER:

- Two Heating Neutral Beam injectors (HNB), each providing about 17MW to the burning plasma, with the possibility to add a third one. The requirements for them are: deuterium beam energy - 1MeV, total current - 40A and beam pulse duration - up to 1h. The prototype is being built at the Neutral Beam Test Facility (NBTF), which is being constructed in Padua, Italy.

- Ion Cyclotron Resonance Heating (ICRH)

- Electron Cyclotron Resonance Heating (ECRH)

Cryostat

The

cryostat is a large 3,800-tonne stainless steel structure surrounding

the vacuum vessel and the superconducting magnets, in order to provide a

super-cool vacuum environment. Its thickness ranging from 50 to 250

millimetres (2.0 to 9.8 in) will allow it to withstand the atmospheric

pressure on the area of a volume of 8,500 cubic meters. The total of 54

modules of the cryostat will be engineered, procured, manufactured, and

installed by Larsen & Toubro Heavy Engineering in India.

Cooling systems

The

ITER tokamak will use three interconnected cooling systems. Most of the

heat will be removed by a primary water cooling loop, itself cooled by

water through a heat exchanger within the tokamak building's secondary

confinement. The secondary cooling loop will be cooled by a larger

complex, comprising a cooling tower, a 5 km (3.1 mi) pipeline supplying

water from Canal de Provence, and basins that allow cooling water to be cooled and tested for chemical contamination and tritium before being released into the Durance River. This system will need to dissipate an average power of 450 MW during the tokamak's operation. A liquid nitrogen system will provide a further 1300 kW of cooling to 80 K (−193.2 °C; −315.7 °F), and a liquid helium system will provide 75 kW

of cooling to 4.5 K (−268.65 °C; −451.57 °F). The liquid helium system

will be designed, manufactured, installed and commissioned by Air Liquide in France.

Location

Location of Cadarache in France

The process of selecting a location for ITER was long and drawn out. The most likely sites were Cadarache in Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur, France, and Rokkasho, Aomori, Japan. Additionally, Canada announced a bid for the site in Clarington in May 2001, but withdrew from the race in 2003. Spain also offered a site at Vandellòs

on 17 April 2002, but the EU decided to concentrate its support solely

behind the French site in late November 2003. From this point on, the

choice was between France and Japan. On 3 May 2005, the EU and Japan

agreed to a process which would settle their dispute by July.

At the final meeting in Moscow on 28 June 2005, the participating parties agreed to construct ITER at Cadarache in Provence-Alpes-Côte-d'Azur, France. Construction of the ITER complex began in 2007, while assembly of the tokamak itself was scheduled to begin in 2015.

Fusion for Energy, the EU agency in charge of the European contribution to the project, is located in Barcelona,

Spain. Fusion for Energy (F4E) is the European Union's Joint

Undertaking for ITER and the Development of Fusion Energy. According to

the agency's website:

F4E is responsible for providing Europe's contribution to ITER, the world's largest scientific partnership that aims to demonstrate fusion as a viable and sustainable source of energy. [...] F4E also supports fusion research and development initiatives [...]

The ITER Neutral Beam Test Facility aimed at developing and optimizing the neutral beam injector prototype, is being constructed in Padova, Italy. It will be the only ITER facility out of the site in Cadarache.

Participants

Thirty-five countries participate in the ITER project.

Currently there are seven parties participating in the ITER program: the European Union (through the legally distinct organisation Euratom), India, Japan, China, Russia, South Korea, and the United States.

Canada was previously a full member, but has since pulled out due to a

lack of funding from the federal government. The lack of funding also

resulted in Canada withdrawing from its bid for the ITER site in 2003.

The host member of the ITER project, and hence the member contributing

most of the costs, is the EU.

In 2007, it was announced that participants in the ITER will consider Kazakhstan's offer to join the program

and in March 2009, Switzerland, an associate member of Euratom since

1979, also ratified the country's accession to the European Domestic

Agency Fusion for Energy as a third country member.

The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom announced on 20 March 2017 that

the UK will be withdrawing from Euratom and future involvement in the

project is unclear. The future of the Joint European Torus

project, which is located in the UK, is also not certain. Some type of

associate membership in Euratom is considered a likely scenario,

possibly similar to Switzerland.

In 2016, ITER announced a partnership with Australia for "technical

cooperation in areas of mutual benefit and interest", but without

Australia becoming a full member.

ITER's work is supervised by the ITER Council, which has the

authority to appoint senior staff, amend regulations, decide on

budgeting issues, and allow additional states or organizations to

participate in ITER. The current Chairman of the ITER Council is Won Namkung, and the ITER Director-General is Bernard Bigot.

- Participants

Funding

As of 2016, the total price of constructing the experiment is expected to be in excess of €20 billion, an increase of €4.6 billion of its 2010 estimate, and of €9.6 billion from the 2009 estimate.

Prior to that, the proposed costs for ITER were €5 billion for the

construction and €5 billion for maintenance and the research connected

with it during its 35-year lifetime. At the June 2005 conference in

Moscow the participating members of the ITER cooperation agreed on the

following division of funding contributions: 45% by the hosting member,

the European Union, and the rest split between the non-hosting members –

China, India, Japan, South Korea, the Russian Federation and the USA.

During the operation and deactivation phases, Euratom will contribute to

34% of the total costs.

Although Japan's financial contribution as a non-hosting member

is one-eleventh of the total, the EU agreed to grant it a special status

so that Japan will provide for two-elevenths of the research staff at

Cadarache and be awarded two-elevenths of the construction contracts,

while the European Union's staff and construction components

contributions will be cut from five-elevenths to four-elevenths.

It was reported in December 2010 that the European Parliament had

refused to approve a plan by member states to reallocate €1.4 billion

from the budget to cover a shortfall in ITER building costs in 2012–13.

The closure of the 2010 budget required this financing plan to be

revised, and the European Commission (EC) was forced to put forward an

ITER budgetary resolution proposal in 2011.

The U.S. withdrew from the ITER consortium in 2000. In 2006, Congress voted to rejoin, and again contribute financially.

Criticism

Protest

against ITER in France, 2009. Construction of the ITER facility began

in 2007, but the project has run into many delays and budget overruns. The World Nuclear Association says that fusion "presents so far insurmountable scientific and engineering challenges".

A technical concern is that the 14 MeV neutrons produced by the fusion reactions will damage the materials from which the reactor is built.

Research is in progress to determine whether and how reactor walls can

be designed to last long enough to make a commercial power station

economically viable in the presence of the intense neutron bombardment.

The damage is primarily caused by high energy neutrons knocking atoms

out of their normal position in the crystal lattice. A related problem

for a future commercial fusion power station is that the neutron

bombardment will induce radioactivity in the reactor material itself.

Maintaining and decommissioning a commercial reactor may thus be

difficult and expensive. Another problem is that superconducting magnets

are damaged by neutron fluxes. A new special research facility, IFMIF, is planned to investigate this problem.

Another source of concern comes from the 2013 tokamak parameters database interpolation which says that power load on tokamak divertors

will be five times the expected value for ITER and much more for actual

electricity-generating reactors. Given that the projected power load on

the ITER divertor is already very high, these new findings mean that

new divertor designs should be urgently tested. However, the corresponding test facility (ADX) has not received any funding as of 2018.

A number of fusion researchers working on non-tokamak systems, such as Robert Bussard and Eric Lerner,

have been critical of ITER for diverting funding from what they believe

could be a potentially more viable and/or cost-effective path to fusion

power, such as the polywell reactor.

Many critics accuse ITER researchers of being unwilling to face up to

the technical and economic potential problems posed by tokamak fusion

schemes.

The expected cost of ITER has risen from US$5 billion to US$20 billion,

and the timeline for operation at full power was moved from the

original estimate of 2016 to 2027.

A French association including about 700 anti-nuclear groups, Sortir du nucléaire

(Get Out of Nuclear Energy), claimed that ITER was a hazard because

scientists did not yet know how to manipulate the high-energy deuterium

and tritium hydrogen isotopes used in the fusion process.

Rebecca Harms, Green/EFA member of the European Parliament's

Committee on Industry, Research and Energy, said: "In the next 50

years, nuclear fusion will neither tackle climate change nor guarantee

the security of our energy supply." Arguing that the EU's energy

research should be focused elsewhere, she said: "The Green/EFA group

demands that these funds be spent instead on energy research that is

relevant to the future. A major focus should now be put on renewable

sources of energy." French Green party lawmaker Noël Mamère

claims that more concrete efforts to fight present-day global warming

will be neglected as a result of ITER: "This is not good news for the

fight against the greenhouse effect because we're going to put ten

billion euros towards a project that has a term of 30–50 years when

we're not even sure it will be effective."

ITER is not designed to produce electricity, but made as a proof of concept reactor for the later DEMO project.

A list of ITER suppliers isn't officially published.

Responses to criticism

Proponents

believe that much of the ITER criticism is misleading and inaccurate,

in particular the allegations of the experiment's "inherent danger." The

stated goals for a commercial fusion power station design are that the

amount of radioactive waste

produced should be hundreds of times less than that of a fission

reactor, and that it should produce no long-lived radioactive waste, and

that it is impossible for any such reactor to undergo a large-scale runaway chain reaction.

A direct contact of the plasma with ITER inner walls would contaminate

it, causing it to cool immediately and stop the fusion process. In

addition, the amount of fuel contained in a fusion reactor chamber (one

half gram of deuterium/tritium fuel)

is only sufficient to sustain the fusion burn pulse from minutes up to

an hour at most, whereas a fission reactor usually contains several

years' worth of fuel.

Moreover, some detritiation systems will be implemented, so that at a

fuel cycle inventory level of about 2 kg (4.4 lb), ITER will eventually

need to recycle large amounts of tritium and at turnovers orders of

magnitude higher than any preceding tritium facility worldwide.

In the case of an accident (or sabotage), it is expected that a

fusion reactor would release far less radioactive pollution than would

an ordinary fission nuclear station. Furthermore, ITER's type of fusion

power has little in common with nuclear weapons technology, and does not

produce the fissile materials necessary for the construction of a

weapon. Proponents note that large-scale fusion power would be able to

produce reliable electricity on demand, and with virtually zero

pollution (no gaseous CO2, SO2, or NOx by-products are produced).

According to researchers at a demonstration reactor in Japan, a

fusion generator should be feasible in the 2030s and no later than the

2050s. Japan is pursuing its own research program with several

operational facilities that are exploring several fusion paths.

In the United States alone, electricity accounts for US$210 billion in annual sales. Asia's electricity sector attracted US$93 billion in private investment between 1990 and 1999.

These figures take into account only current prices. Proponents of ITER

contend that an investment in research now should be viewed as an

attempt to earn a far greater future return.

Also, worldwide investment of less than US$1 billion per year into ITER

is not incompatible with concurrent research into other methods of

power generation, which in 2007 totaled US$16.9 billion.

Supporters of ITER emphasize that the only way to test ideas for

withstanding the intense neutron flux is to experimentally subject

materials to that flux, which is one of the primary missions of ITER and

the IFMIF, and both facilities will be vitally important to that effort.

The purpose of ITER is to explore the scientific and engineering

questions that surround potential fusion power stations. It is nearly

impossible to acquire satisfactory data for the properties of materials

expected to be subject to an intense neutron flux, and burning plasmas

are expected to have quite different properties from externally heated

plasmas.

Supporters contend that the answer to these questions requires the ITER

experiment, especially in the light of the monumental potential

benefits.

Furthermore, the main line of research via tokamaks

has been developed to the point that it is now possible to undertake

the penultimate step in magnetic confinement plasma physics research

with a self-sustained reaction. In the tokamak research program, recent

advances devoted to controlling the configuration of the plasma have led

to the achievement of substantially improved energy and pressure

confinement, which reduces the projected cost of electricity from such

reactors by a factor of two to a value only about 50% more than the

projected cost of electricity from advanced light-water reactors.

In addition, progress in the development of advanced, low activation

structural materials supports the promise of environmentally benign

fusion reactors and research into alternate confinement concepts is

yielding the promise of future improvements in confinement. Finally, supporters contend that other potential replacements to the fossil fuels have environmental issues of their own. Solar, wind, and hydroelectric power all have a relatively low power output per square kilometer compared to ITER's successor DEMO which, at 2,000 MW, would have an energy density that exceeds even large fission power stations.