Four-hour time lapse exposure of the sky

Leonids from space

A meteor shower is a celestial event in which a number of meteors are observed to radiate, or originate, from one point in the night sky. These meteors are caused by streams of cosmic debris called meteoroids entering Earth's atmosphere

at extremely high speeds on parallel trajectories. Most meteors are

smaller than a grain of sand, so almost all of them disintegrate and

never hit the Earth's surface. Very intense or unusual meteor showers

are known as meteor outbursts and meteor storms, which produce at least 1,000 meteors an hour, most notably from the Leonids. The Meteor Data Centre lists over 900 suspected meteor showers of which about 100 are well established. Several organizations point to viewing opportunities on the Internet.

Historical developments

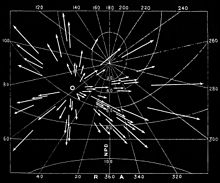

Diagram from 1872

The first great meteor storm in the modern era was the Leonids of November 1833. One estimate is a peak rate of over one hundred thousand meteors an hour, but another, done as the storm abated, estimated in excess of two hundred thousand meteors during the 9 hours of storm, over the entire region of North America east of the Rocky Mountains. American Denison Olmsted

(1791–1859) explained the event most accurately. After spending the

last weeks of 1833 collecting information, he presented his findings in

January 1834 to the American Journal of Science and Arts, published in January–April 1834, and January 1836. He noted the shower was of short duration and was not seen in Europe, and that the meteors radiated from a point in the constellation of Leo and he speculated the meteors had originated from a cloud of particles in space. Work continued, yet coming to understand the annual nature of showers though the occurrences of storms perplexed researchers.

The actual nature of meteors was still debated during the XIX

century. Meteors were conceived as an atmospheric phenomenon by many

scientists (Alexander von Humboldt, Adolphe Qoetelet, Julius Schmidt) until the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli ascertained the relation between meteors and comets in his work "Notes upon the astronomical theory of the falling stars" (1867). In the 1890s, Irish astronomer George Johnstone Stoney (1826–1911) and British astronomer Arthur Matthew Weld Downing

(1850–1917), were the first to attempt to calculate the position of the

dust at Earth's orbit. They studied the dust ejected in 1866 by comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle

in advance of the anticipated Leonid shower return of 1898 and 1899.

Meteor storms were anticipated, but the final calculations showed that

most of the dust would be far inside of Earth's orbit. The same results

were independently arrived at by Adolf Berberich of the Königliches Astronomisches Rechen Institut

(Royal Astronomical Computation Institute) in Berlin, Germany. Although

the absence of meteor storms that season confirmed the calculations,

the advance of much better computing tools was needed to arrive at

reliable predictions.

In 1981 Donald K. Yeomans of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory reviewed the history of meteor showers for the Leonids and the history of the dynamic orbit of Comet Tempel-Tuttle. A graph from it was adapted and re-published in Sky and Telescope.

It showed relative positions of the Earth and Tempel-Tuttle and marks

where Earth encountered dense dust. This showed that the meteoroids are

mostly behind and outside the path of the comet, but paths of the Earth

through the cloud of particles resulting in powerful storms were very

near paths of nearly no activity.

In 1985, E. D. Kondrat'eva and E. A. Reznikov of Kazan State

University first correctly identified the years when dust was released

which was responsible for several past Leonid meteor storms. In 1995, Peter Jenniskens predicted the 1995 Alpha Monocerotids outburst from dust trails. In anticipation of the 1999 Leonid storm, Robert H. McNaught, David Asher, and Finland's Esko Lyytinen were the first to apply this method in the West. In 2006 Jenniskens published predictions for future dust trail encounters covering the next 50 years. Jérémie Vaubaillon continues to update predictions based on observations each year for the Institut de Mécanique Céleste et de Calcul des Éphémérides (IMCCE).

Radiant point

Meteor shower on chart

Because meteor shower particles are all traveling in parallel paths,

and at the same velocity, they will all appear to an observer below to

radiate away from a single point in the sky. This radiant point is caused by the effect of perspective,

similar to parallel railroad tracks converging at a single vanishing

point on the horizon when viewed from the middle of the tracks. Meteor

showers are almost always named after the constellation from which the

meteors appear to originate. This "fixed point" slowly moves across the

sky during the night due to the Earth turning on its axis, the same

reason the stars appear to slowly march across the sky. The radiant also

moves slightly from night to night against the background stars

(radiant drift) due to the Earth moving in its orbit around the sun. See

IMO Meteor Shower Calendar 2017 (International Meteor Organization) for maps of drifting "fixed points."

When the moving radiant is at the highest point it will reach in

the observer's sky that night, the sun will be just clearing the eastern

horizon. For this reason, the best viewing time for a meteor shower is

generally slightly before dawn — a compromise between the maximum number

of meteors available for viewing, and the lightening sky which makes

them harder to see.

Naming

Meteor

showers are named after the nearest constellation or bright star with a

Greek or Roman letter assigned that is close to the radiant position at

the peak of the shower, whereby the grammatical declension of the Latin possessive form

is replaced by "id" or "ids". Hence, meteors radiating from near the

star delta Aquarii (declension "-i") are called delta Aquariids. The

International Astronomical Union's Task Group on Meteor Shower

Nomenclature and the IAU's Meteor Data Center keep track of meteor

shower nomenclature and which showers are established.

Origin of meteoroid streams

Comet Encke's meteoroid trail is the diagonal red glow

Meteoroid trail between fragments of Comet 73P

A meteor shower is the result of an interaction between a planet, such as Earth, and streams of debris from a comet. Comets can produce debris by water vapor drag, as demonstrated by Fred Whipple in 1951, and by breakup. Whipple envisioned comets as "dirty snowballs," made up of rock embedded in ice, orbiting the Sun. The "ice" may be water, methane, ammonia, or other volatiles,

alone or in combination. The "rock" may vary in size from that of a

dust mote to that of a small boulder. Dust mote sized solids are orders of magnitude

more common than those the size of sand grains, which, in turn, are

similarly more common than those the size of pebbles, and so on. When

the ice warms and sublimates, the vapor can drag along dust, sand, and

pebbles.

Each time a comet swings by the Sun in its orbit,

some of its ice vaporizes and a certain amount of meteoroids will be

shed. The meteoroids spread out along the entire orbit of the comet to

form a meteoroid stream, also known as a "dust trail" (as opposed to a

comet's "gas tail" caused by the very small particles that are quickly

blown away by solar radiation pressure).

Recently, Peter Jenniskens

has argued that most of our short-period meteor showers are not from

the normal water vapor drag of active comets, but the product of

infrequent disintegrations, when large chunks break off a mostly dormant

comet. Examples are the Quadrantids and Geminids, which originated from a breakup of asteroid-looking objects, 2003 EH1 and 3200 Phaethon,

respectively, about 500 and 1000 years ago. The fragments tend to fall

apart quickly into dust, sand, and pebbles, and spread out along the

orbit of the comet to form a dense meteoroid stream, which subsequently

evolves into Earth's path.

Dynamical evolution of meteoroid streams

Shortly

after Whipple predicted that dust particles travelled at low speeds

relative to the comet, Milos Plavec was the first to offer the idea of a

dust trail, when he calculated how meteoroids, once freed from

the comet, would drift mostly in front of or behind the comet after

completing one orbit. The effect is simple celestial mechanics –

the material drifts only a little laterally away from the comet while

drifting ahead or behind the comet because some particles make a wider

orbit than others.

These dust trails are sometimes observed in comet images taken at mid

infrared wavelengths (heat radiation), where dust particles from the

previous return to the Sun are spread along the orbit of the comet.

The gravitational pull of the planets determines where the dust

trail would pass by Earth orbit, much like a gardener directing a hose

to water a distant plant. Most years, those trails would miss the Earth

altogether, but in some years the Earth is showered by meteors. This

effect was first demonstrated from observations of the 1995 alpha Monocerotids, and from earlier not widely known identifications of past earth storms.

Over longer periods of time, the dust trails can evolve in

complicated ways. For example, the orbits of some repeating comets, and

meteoroids leaving them, are in resonant orbits with Jupiter

or one of the other large planets – so many revolutions of one will

equal another number of revolutions of the other. This creates a shower

component called a filament.

A second effect is a close encounter with a planet. When the

meteoroids pass by Earth, some are accelerated (making wider orbits

around the Sun), others are decelerated (making shorter orbits),

resulting in gaps in the dust trail in the next return (like opening a

curtain, with grains piling up at the beginning and end of the gap).

Also, Jupiter's perturbation can change sections of the dust trail

dramatically, especially for short period comets, when the grains

approach the big planet at their furthest point along the orbit around

the Sun, moving most slowly. As a result, the trail has a clumping, a braiding or a tangling of crescents, of each individual release of material.

The third effect is that of radiation pressure which will push less massive particles into orbits further from the sun – while more massive objects (responsible for bolides or fireballs)

will tend to be affected less by radiation pressure. This makes some

dust trail encounters rich in bright meteors, others rich in faint

meteors.

Over time, these effects disperse the meteoroids and create a broader

stream. The meteors we see from these streams are part of annual showers, because Earth encounters those streams every year at much the same rate.

When the meteoroids collide with other meteoroids in the zodiacal cloud,

they lose their stream association and become part of the "sporadic

meteors" background. Long since dispersed from any stream or trail, they

form isolated meteors, not a part of any shower. These random meteors

will not appear to come from the radiant of the main shower.

Famous meteor showers

Perseids and Leonids

The most visible meteor shower in most years are the Perseids, which peak on 12 August of each year at over one meteor per minute. NASA has a useful tool to calculate how many meteors per hour are visible from one's observing location.

The Leonid

meteor shower peaks around 17 November of each year. Approximately

every 33 years, the Leonid shower produces a meteor storm, peaking at

rates of thousands of meteors per hour. Leonid storms gave birth to the

term meteor shower when it was first realised that, during the

November 1833 storm, the meteors radiated from near the star Gamma

Leonis. The last Leonid storms were in 1999, 2001 (two), and 2002 (two).

Before that, there were storms in 1767, 1799, 1833, 1866, 1867, and

1966. When the Leonid shower is not storming, it is less active than the Perseids.

Other meteor showers

Established meteor showers

Official names are given in the International Astronomical Union's list of meteor showers.

| Shower | Time | Parent object |

|---|---|---|

| Quadrantids | early January | The same as the parent object of minor planet 2003 EH1, and Comet C/1490 Y1. Comet C/1385 U1 has also been studied as a possible source. |

| Lyrids | late April | Comet Thatcher |

| Pi Puppids (periodic) | late April | Comet 26P/Grigg-Skjellerup |

| Eta Aquariids | early May | Comet 1P/Halley |

| Arietids | mid-June | Comet 96P/Machholz, Marsden and Kracht comet groups complex |

| June Bootids (periodic) | late June | Comet 7P/Pons-Winnecke |

| Southern Delta Aquariids | late July | Comet 96P/Machholz, Marsden and Kracht comet groups complex |

| Alpha Capricornids | late July | Comet 169P/NEAT |

| Perseids | mid-August | Comet 109P/Swift-Tuttle |

| Kappa Cygnids | mid-August | Minor planet 2008 ED69 |

| Aurigids (periodic) | early September | Comet C/1911 N1 (Kiess) |

| Draconids (periodic) | early October | Comet 21P/Giacobini-Zinner |

| Orionids | late October | Comet 1P/Halley |

| Southern Taurids | early November | Comet 2P/Encke |

| Northern Taurids | mid-November | Minor planet 2004 TG10 and others |

| Andromedids (periodic) | mid-November | Comet 3D/Biela |

| Alpha Monocerotids (periodic) | mid-November | unknown |

| Leonids | mid-November | Comet 55P/Tempel-Tuttle |

| Phoenicids (periodic) | early December | Comet 289P/Blanpain |

| Geminids | mid-December | Minor planet 3200 Phaethon |

| Ursids | late December | Comet 8P/Tuttle |

Extraterrestrial meteor showers

Mars meteor by MER Spirit rover

Any other solar system body with a reasonably transparent atmosphere

can also have meteor showers. As the Moon is in the neighborhood of

Earth it can experience the same showers, but will have its own

phenomena due to its lack of an atmosphere per se, such as vastly increasing its sodium tail. NASA now maintains an ongoing database of observed impacts on the moon maintained by the Marshall Space Flight Center whether from a shower or not.

Many planets and moons have impact craters dating back large

spans of time. But new craters, perhaps even related to meteor showers

are possible. Mars, and thus its moons, is known to have meteor showers.

These have not been observed on other planets as yet but may be

presumed to exist. For Mars in particular, although these are different

from the ones seen on Earth because the different orbits of Mars and

Earth relative to the orbits of comets. The Martian atmosphere has less

than one percent of the density of Earth's at ground level, at their

upper edges, where meteoroids strike, the two are more similar. Because

of the similar air pressure at altitudes for meteors, the effects are

much the same. Only the relatively slower motion of the meteoroids due

to increased distance from the sun should marginally decrease meteor

brightness. This is somewhat balanced in that the slower descent means

that Martian meteors have more time in which to ablate.

On March 7, 2004, the panoramic camera on Mars Exploration Rover Spirit recorded a streak which is now believed to have been caused by a meteor from a Martian meteor shower associated with comet 114P/Wiseman-Skiff.

A strong display from this shower was expected on December 20, 2007.

Other showers speculated about are a "Lambda Geminid" shower associated

with the Eta Aquariids of Earth (i.e., both associated with Comet 1P/Halley), a "Beta Canis Major" shower associated with Comet 13P/Olbers, and "Draconids" from 5335 Damocles.

Isolated massive impacts have been observed at Jupiter: The 1994 Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 which formed a brief trail as well, and successive events since then (see List of Jupiter events.) Meteors or meteor showers have been discussed for most of the objects in the solar system with an atmosphere: Mercury, Venus, Saturn's moon Titan, Neptune's moon Triton, and Pluto.