| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | lustrous, metallic, and silver with a gold tinge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(Ni) | 58.6934(4) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickel in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 28 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 10 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Element category | transition metal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ar] 3d8 4s2 or [Ar] 3d9 4s1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell

| 2, 8, 16, 2 or 2, 8, 17, 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 1728 K (1455 °C, 2651 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 3003 K (2730 °C, 4946 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 8.908 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 7.81 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 17.48 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 379 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 26.07 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | −2, −1, +1, +2, +3, +4 (a mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 1.91 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 124 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 124±4 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 163 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of nickel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | face-centered cubic (fcc) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 4900 m/s (at r.t.) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 13.4 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 90.9 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 69.3 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | ferromagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 200 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 76 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 180 GPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poisson ratio | 0.31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 4.0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vickers hardness | 638 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 667–1600 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-02-0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Axel Fredrik Cronstedt (1751) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of nickel | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel belongs to the transition metals and is hard and ductile. Pure nickel, powdered to maximize the reactive surface area, shows a significant chemical activity, but larger pieces are slow to react with air under standard conditions because an oxide layer forms on the surface and prevents further corrosion (passivation). Even so, pure native nickel is found in Earth's crust only in tiny amounts, usually in ultramafic rocks, and in the interiors of larger nickel–iron meteorites that were not exposed to oxygen when outside Earth's atmosphere.

Meteoric nickel is found in combination with iron, a reflection of the origin of those elements as major end products of supernova nucleosynthesis. An iron–nickel mixture is thought to compose Earth's inner core.

Use of nickel (as a natural meteoric nickel–iron alloy) has been traced as far back as 3500 BCE. Nickel was first isolated and classified as a chemical element in 1751 by Axel Fredrik Cronstedt, who initially mistook the ore for a copper mineral, in the cobalt mines of Los, Hälsingland, Sweden. The element's name comes from a mischievous sprite of German miner mythology, Nickel (similar to Old Nick), who personified the fact that copper-nickel ores resisted refinement into copper. An economically important source of nickel is the iron ore limonite, which often contains 1–2% nickel. Nickel's other important ore minerals include pentlandite and a mixture of Ni-rich natural silicates known as garnierite. Major production sites include the Sudbury region in Canada (which is thought to be of meteoric origin), New Caledonia in the Pacific, and Norilsk in Russia.

Nickel is slowly oxidized by air at room temperature and is considered corrosion-resistant. Historically, it has been used for plating iron and brass, coating chemistry equipment, and manufacturing certain alloys that retain a high silvery polish, such as German silver. About 9% of world nickel production is still used for corrosion-resistant nickel plating. Nickel-plated objects sometimes provoke nickel allergy. Nickel has been widely used in coins, though its rising price has led to some replacement with cheaper metals in recent years.

Nickel is one of four elements (the others are iron, cobalt, and gadolinium) that are ferromagnetic at approximately room temperature. Alnico permanent magnets based partly on nickel are of intermediate strength between iron-based permanent magnets and rare-earth magnets. The metal is valuable in modern times chiefly in alloys; about 68% of world production is used in stainless steel. A further 10% is used for nickel-based and copper-based alloys, 7% for alloy steels, 3% in foundries, 9% in plating and 4% in other applications, including the fast-growing battery sector. As a compound, nickel has a number of niche chemical manufacturing uses, such as a catalyst for hydrogenation, cathodes for batteries, pigments and metal surface treatments. Nickel is an essential nutrient for some microorganisms and plants that have enzymes with nickel as an active site.

Properties

Atomic and physical properties

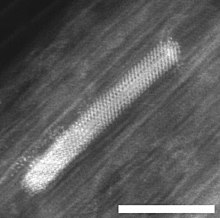

Electron micrograph of a Ni nanocrystal inside a single wall carbon nanotube; scale bar 5 nm.

Nickel is a silvery-white metal with a slight golden tinge that takes

a high polish. It is one of only four elements that are magnetic at or

near room temperature, the others being iron, cobalt and gadolinium. Its Curie temperature is 355 °C (671 °F), meaning that bulk nickel is non-magnetic above this temperature. The unit cell of nickel is a face-centered cube with the lattice parameter of 0.352 nm, giving an atomic radius

of 0.124 nm. This crystal structure is stable to pressures of at least

70 GPa. Nickel belongs to the transition metals. It is hard, malleable

and ductile, and has a relatively high for transition metals electrical and thermal conductivity. The high compressive strength of 34 GPa, predicted for ideal crystals, is never obtained in the real bulk material due to the formation and movement of dislocations; however, it has been reached in Ni nanoparticles.

Electron configuration dispute

The nickel atom has two electron configurations, [Ar] 3d8 4s2 and [Ar] 3d9 4s1, which are very close in energy – the symbol [Ar] refers to the argon-like core structure. There is some disagreement on which configuration has the lowest energy. Chemistry textbooks quote the electron configuration of nickel as [Ar] 4s2 3d8, which can also be written [Ar] 3d8 4s2. This configuration agrees with the Madelung energy ordering rule,

which predicts that 4s is filled before 3d. It is supported by the

experimental fact that the lowest energy state of the nickel atom is a

3d8 4s2 energy level, specifically the 3d8(3F) 4s2 3F, J = 4 level.

However, each of these two configurations splits into several energy levels due to fine structure, and the two sets of energy levels overlap. The average energy of states with configuration [Ar] 3d9 4s1 is actually lower than the average energy of states with configuration [Ar] 3d8 4s2. For this reason, the research literature on atomic calculations quotes the ground state configuration of nickel as [Ar] 3d9 4s1.

Isotopes

Naturally occurring nickel is composed of five stable isotopes; 58Ni, 60Ni, 61Ni, 62Ni and 64Ni, with 58Ni being the most abundant (68.077% natural abundance). Isotopes heavier than 62Ni cannot be formed by nuclear fusion without losing energy.

Nickel-62 has the highest mean nuclear binding energy per nucleon of any nuclide, at 8.7946 MeV/nucleon. Its binding energy is greater than both 56Fe and 58Fe, more abundant elements often incorrectly cited as having the most tightly-bound nuclides. Although this would seem to predict nickel-62 as the most abundant heavy element in the universe, the relatively high rate of photodisintegration of nickel in stellar interiors causes iron to be by far the most abundant.

Stable isotope nickel-60 is the daughter product of the extinct radionuclide 60Fe, which decays with a half-life of 2.6 million years. Because 60Fe has such a long half-life, its persistence in materials in the solar system may generate observable variations in the isotopic composition of 60Ni. Therefore, the abundance of 60Ni present in extraterrestrial material may provide insight into the origin of the solar system and its early history.

Some 18 nickel radioisotopes have been characterised, the most stable being 59Ni with a half-life of 76,000 years, 63Ni with 100 years, and 56Ni with 6 days. All of the remaining radioactive

isotopes have half-lives that are less than 60 hours and the majority

of these have half-lives that are less than 30 seconds. This element

also has one meta state.

Radioactive nickel-56 is produced by the silicon burning process and later set free in large quantities during type Ia supernovae. The shape of the light curve of these supernovae at intermediate to late-times corresponds to the decay via electron capture of nickel-56 to cobalt-56 and ultimately to iron-56. Nickel-59 is a long-lived cosmogenic radionuclide with a half-life of 76,000 years. 59Ni has found many applications in isotope geology. 59Ni has been used to date the terrestrial age of meteorites and to determine abundances of extraterrestrial dust in ice and sediment. Nickel-78's half-life was recently measured at 110 milliseconds, and is believed an important isotope in supernova nucleosynthesis of elements heavier than iron. The nuclide 48Ni, discovered in 1999, is the most proton-rich heavy element isotope known. With 28 protons and 20 neutrons 48Ni is "double magic", as is 78Ni with 28 protons and 50 neutrons. Both are therefore unusually stable for nuclides with so large a proton-neutron imbalance.

Occurrence

Widmanstätten pattern showing the two forms of nickel-iron, kamacite and taenite, in an octahedrite meteorite

On Earth, nickel occurs most often in combination with sulfur and iron in pentlandite, with sulfur in millerite, with arsenic in the mineral nickeline, and with arsenic and sulfur in nickel galena. Nickel is commonly found in iron meteorites as the alloys kamacite and taenite.

The bulk of the nickel is mined from two types of ore deposits. The first is laterite, where the principal ore mineral mixtures are nickeliferous limonite, (Fe,Ni)O(OH), and garnierite (a mixture of various hydrous nickel and nickel-rich silicates). The second is magmatic sulfide deposits, where the principal ore mineral is pentlandite: (Ni,Fe)

9S

8.

9S

8.

Australia and New Caledonia have the biggest estimate reserves, at 45% of world's total.

Identified land-based resources throughout the world averaging 1%

nickel or greater comprise at least 130 million tons of nickel (about

the double of known reserves). About 60% is in laterites and 40% in sulfide deposits.

On geophysical evidence, most of the nickel on Earth is believed to be in the Earth's outer and inner cores. Kamacite and taenite are naturally occurring alloys of iron and nickel. For kamacite, the alloy is usually in the proportion of 90:10 to 95:5, although impurities (such as cobalt or carbon) may be present, while for taenite the nickel content is between 20% and 65%. Kamacite and taenite are also found in nickel iron meteorites.

Compounds

Tetracarbonyl nickel

The most common oxidation state of nickel is +2, but compounds of Ni0, Ni+, and Ni3+ are well known, and the exotic oxidation states Ni2−, Ni1−, and Ni4+ have been produced and studied.

Nickel(0)

Nickel tetracarbonyl (Ni(CO)

4), discovered by Ludwig Mond, is a volatile, highly toxic liquid at room temperature. On heating, the complex decomposes back to nickel and carbon monoxide:

4), discovered by Ludwig Mond, is a volatile, highly toxic liquid at room temperature. On heating, the complex decomposes back to nickel and carbon monoxide:

- Ni(CO)

4 ⇌ Ni + 4 CO

This behavior is exploited in the Mond process for purifying nickel, as described above. The related nickel(0) complex bis(cyclooctadiene)nickel(0) is a useful catalyst in organonickel chemistry because the cyclooctadiene (or cod) ligands are easily displaced.

Nickel(I)

Nickel(I) complexes are uncommon, but one example is the tetrahedral complex NiBr(PPh3)3. Many nickel(I) complexes feature Ni-Ni bonding, such as the dark red diamagnetic K

4[Ni

2(CN)

6] prepared by reduction of K

2[Ni

2(CN)

6] with sodium amalgam. This compound is oxidised in water, liberating H

2.

4[Ni

2(CN)

6] prepared by reduction of K

2[Ni

2(CN)

6] with sodium amalgam. This compound is oxidised in water, liberating H

2.

It is thought that the nickel(I) oxidation state is important to nickel-containing enzymes, such as [NiFe]-hydrogenase, which catalyzes the reversible reduction of protons to H

2.

2.

Nickel(II)

Color of various Ni(II) complexes in aqueous solution. From left to right, [Ni(NH

3)

6]2+, [Ni(C2H4(NH2)2)]2+, [NiCl

4]2−, [Ni(H

2O)

6]2+

3)

6]2+, [Ni(C2H4(NH2)2)]2+, [NiCl

4]2−, [Ni(H

2O)

6]2+

Crystals of hydrated nickel sulfate.

Nickel(II) forms compounds with all common anions, including sulfide, sulfate, carbonate, hydroxide, carboxylates, and halides. Nickel(II) sulfate is produced in large quantities by dissolving nickel metal or oxides in sulfuric acid, forming both a hexa- and heptahydrates useful for electroplating nickel. Common salts of nickel, such as the chloride, nitrate, and sulfate, dissolve in water to give green solutions of the metal aquo complex [Ni(H

2O)

6]2+.

2O)

6]2+.

The four halides form nickel compounds, which are solids with molecules that feature octahedral Ni centres. Nickel(II) chloride

is most common, and its behavior is illustrative of the other halides.

Nickel(II) chloride is produced by dissolving nickel or its oxide in hydrochloric acid. It is usually encountered as the green hexahydrate, the formula of which is usually written NiCl2•6H2O. When dissolved in water, this salt forms the metal aquo complex [Ni(H

2O)

6]2+. Dehydration of NiCl2•6H2O gives the yellow anhydrous NiCl

2.

2O)

6]2+. Dehydration of NiCl2•6H2O gives the yellow anhydrous NiCl

2.

Some tetracoordinate nickel(II) complexes, e.g. bis(triphenylphosphine)nickel chloride, exist both in tetrahedral and square planar geometries. The tetrahedral complexes are paramagnetic, whereas the square planar complexes are diamagnetic.

In having properties of magnetic equilibrium and formation of

octahedral complexes, they contrast with the divalent complexes of the

heavier group 10 metals, palladium(II) and platinum(II), which form only

square-planar geometry.

Nickelocene is known; it has an electron count of 20, making it relatively unstable.

Nickel(III) antimonide

Nickel(III) and (IV)

Numerous Ni(III) compounds are known, with the first such examples being Nickel(III) trihalophosphines (NiIII(PPh3)X3). Further, Ni(III) forms simple salts with fluoride or oxide ions. Ni(III) can be stabilized by σ-donor ligands such as thiols and phosphines.

Ni(IV) is present in the mixed oxide BaNiO

3, while Ni(III) is present in nickel oxide hydroxide, which is used as the cathode in many rechargeable batteries, including nickel-cadmium, nickel-iron, nickel hydrogen, and nickel-metal hydride, and used by certain manufacturers in Li-ion batteries. Ni(IV) remains a rare oxidation state of nickel and very few compounds are known to date.

3, while Ni(III) is present in nickel oxide hydroxide, which is used as the cathode in many rechargeable batteries, including nickel-cadmium, nickel-iron, nickel hydrogen, and nickel-metal hydride, and used by certain manufacturers in Li-ion batteries. Ni(IV) remains a rare oxidation state of nickel and very few compounds are known to date.

History

Because the ores of nickel are easily mistaken for ores of silver,

understanding of this metal and its use dates to relatively recent

times. However, the unintentional use of nickel is ancient, and can be

traced back as far as 3500 BCE. Bronzes from what is now Syria have been found to contain as much as 2% nickel. Some ancient Chinese manuscripts suggest that "white copper" (cupronickel, known as baitong)

was used there between 1700 and 1400 BCE. This Paktong white copper was

exported to Britain as early as the 17th century, but the nickel

content of this alloy was not discovered until 1822. Coins of nickel-copper alloy were minted by the Bactrian kings Agathocles, Euthydemus II and Pantaleon in the 2nd Century BCE, possibly out of the Chinese cupronickel.

nickeline/niccolite

In medieval Germany, a red mineral was found in the Erzgebirge

(Ore Mountains) that resembled copper ore. However, when miners were

unable to extract any copper from it, they blamed a mischievous sprite

of German mythology, Nickel (similar to Old Nick), for besetting the copper. They called this ore Kupfernickel from the German Kupfer for copper. This ore is now known to be nickeline, a nickel arsenide. In 1751, Baron Axel Fredrik Cronstedt tried to extract copper from kupfernickel at a cobalt mine in the Swedish village of Los, and instead produced a white metal that he named after the spirit that had given its name to the mineral, nickel. In modern German, Kupfernickel or Kupfer-Nickel designates the alloy cupronickel.

Originally, the only source for nickel was the rare Kupfernickel. Beginning in 1824, nickel was obtained as a byproduct of cobalt blue production. The first large-scale smelting of nickel began in Norway in 1848 from nickel-rich pyrrhotite. The introduction of nickel in steel production in 1889 increased the demand for nickel, and the nickel deposits of New Caledonia, discovered in 1865, provided most of the world's supply between 1875 and 1915. The discovery of the large deposits in the Sudbury Basin, Canada in 1883, in Norilsk-Talnakh, Russia in 1920, and in the Merensky Reef, South Africa in 1924, made large-scale production of nickel possible.

Coinage

Dutch coins made of pure nickel

Aside from the aforementioned Bactrian coins, nickel was not a component of coins until the mid-19th century.

Canada

99.9% nickel five-cent coins

were struck in Canada (the world's largest nickel producer at the time)

during non-war years from 1922–1981; the metal content made these coins

magnetic.

During the wartime period 1942–45, most or all nickel was removed from

Canadian and U.S. coins to save it for manufacturing armor. Canada used 99.9% nickel from 1968 in its higher-value coins until 2000.

Switzerland

Coins of nearly pure nickel were first used in 1881 in Switzerland.

United Kingdom

Birmingham forged nickel coins in about 1833 for trading in Malaya.

United States

In the United States, the term "nickel" or "nick" originally applied to the copper-nickel Flying Eagle cent, which replaced copper with 12% nickel 1857–58, then the Indian Head cent of the same alloy from 1859–1864. Still later, in 1865, the term designated the three-cent nickel, with nickel increased to 25%. In 1866, the five-cent shield nickel

(25% nickel, 75% copper) appropriated the designation. Along with the

alloy proportion, this term has been used to the present in the United

States.

Current use

In the 21st century, the high price of nickel has led to some

replacement of the metal in coins around the world. Coins still made

with nickel alloys include one- and two-euro coins, 5¢, 10¢, 25¢ and 50¢ U.S. coins, and 20p, 50p, £1 and £2 UK coins.

Nickel-alloy in 5p and 10p UK coins was replaced with nickel-plated

steel began in 2012, causing allergy problems for some people and public

controversy.

World production

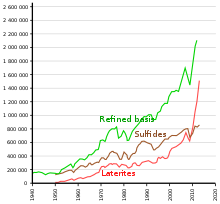

Time trend of nickel production

Nickel ores grade evolution in some leading nickel producing countries.

More thant 2 million tonnes of nickel per year are mined worldwide, with Indonesia (560 t), The Philippines (340 t), Russia (210 t), New Caledonia (210 t), Australia (170 t) and Canada (160 t) being the largest producers as of 2019. The largest deposits of nickel in non-Russian Europe are located in Finland and Greece.

Identified land-based resources averaging 1% nickel or greater contain

at least 130 million tons of nickel. Approximately 60% is in laterites

and 40% is in sulfide deposits. In addition, extensive deep-sea

resources of nickel are in manganese crusts and nodules covering large

areas of the ocean floor, particularly in the Pacific Ocean.

The one locality in the United States where nickel has been profitably mined is Riddle, Oregon, where several square miles of nickel-bearing garnierite surface deposits are located. The mine closed in 1987. The Eagle mine project is a new nickel mine in Michigan's upper peninsula. Construction was completed in 2013, and operations began in the third quarter of 2014. In the first full year of operation, Eagle Mine produced 18,000 tonnes.

Extraction and purification

Evolution of the annual nickel extraction, according to ores.

Nickel is obtained through extractive metallurgy:

it is extracted from the ore by conventional roasting and reduction

processes that yield a metal of greater than 75% purity. In many stainless steel applications, 75% pure nickel can be used without further purification, depending on the impurities.

Traditionally, most sulfide ores have been processed using pyrometallurgical techniques to produce a matte for further refining. Recent advances in hydrometallurgical techniques

resulted in significantly purer metallic nickel product. Most sulfide

deposits have traditionally been processed by concentration through a froth flotation process followed by pyrometallurgical

extraction. In hydrometallurgical processes, nickel sulfide ores are

concentrated with flotation (differential flotation if Ni/Fe ratio is

too low) and then smelted. The nickel matte is further processed with

the Sherritt-Gordon process. First, copper is removed by adding hydrogen sulfide,

leaving a concentrate of cobalt and nickel. Then, solvent extraction is

used to separate the cobalt and nickel, with the final nickel content

greater than 99%.

Electrolytically refined nickel nodule, with green, crystallized nickel-electrolyte salts visible in the pores.

Electrorefining

A second common refining process is leaching the metal matte into a

nickel salt solution, followed by the electro-winning of the nickel from

solution by plating it onto a cathode as electrolytic nickel.

Mond process

Highly purified nickel spheres made by the Mond process.

The purest metal is obtained from nickel oxide by the Mond process, which achieves a purity of greater than 99.99%.

The process was patented by Ludwig Mond and has been in industrial use

since before the beginning of the 20th century. In this process, nickel

is reacted with carbon monoxide in the presence of a sulfur catalyst at around 40–80 °C to form nickel carbonyl. Iron gives iron pentacarbonyl, too, but this reaction is slow. If necessary, the nickel may be separated by distillation. Dicobalt octacarbonyl is also formed in nickel distillation as a by-product, but it decomposes to tetracobalt dodecacarbonyl at the reaction temperature to give a non-volatile solid.

Nickel is obtained from nickel carbonyl by one of two processes.

It may be passed through a large chamber at high temperatures in which

tens of thousands of nickel spheres, called pellets, are constantly

stirred. The carbonyl decomposes and deposits pure nickel onto the

nickel spheres. In the alternate process, nickel carbonyl is decomposed

in a smaller chamber at 230 °C to create a fine nickel powder. The

byproduct carbon monoxide is recirculated and reused. The highly pure

nickel product is known as "carbonyl nickel".

Metal value

The market price of nickel surged throughout 2006 and the early months of 2007; as of April 5, 2007, the metal was trading at US$52,300/tonne or $1.47/oz. The price subsequently fell dramatically, and as of September 2017, the metal was trading at $11,000/tonne, or $0.31/oz.

The US nickel coin

contains 0.04 ounces (1.1 g) of nickel, which at the April 2007 price

was worth 6.5 cents, along with 3.75 grams of copper worth about 3

cents, with a total metal value of more than 9 cents. Since the face

value of a nickel is 5 cents, this made it an attractive target for

melting by people wanting to sell the metals at a profit. However, the United States Mint,

in anticipation of this practice, implemented new interim rules on

December 14, 2006, subject to public comment for 30 days, which

criminalized the melting and export of cents and nickels. Violators can be punished with a fine of up to $10,000 and/or imprisoned for a maximum of five years.

As of September 19, 2013, the melt value of a U.S. nickel (copper

and nickel included) is $0.045, which is 90% of the face value.

Applications

Nickel foam (top) and its internal structure (bottom)

The global production of nickel is presently used as follows: 68% in stainless steel; 10% in nonferrous alloys; 9% in electroplating; 7% in alloy steel; 3% in foundries; and 4% other uses (including batteries).

Nickel is used in many specific and recognizable industrial and consumer products, including stainless steel, alnico magnets, coinage, rechargeable batteries, electric guitar strings, microphone capsules, plating on plumbing fixtures, and special alloys such as permalloy, elinvar, and invar.

It is used for plating and as a green tint in glass. Nickel is

preeminently an alloy metal, and its chief use is in nickel steels and

nickel cast irons, in which it typically increases the tensile strength,

toughness, and elastic limit. It is widely used in many other alloys,

including nickel brasses and bronzes and alloys with copper, chromium,

aluminium, lead, cobalt, silver, and gold (Inconel, Incoloy, Monel, Nimonic).

A "horseshoe magnet" made of alnico nickel alloy.

Because it is resistant to corrosion, nickel was occasionally used as

a substitute for decorative silver. Nickel was also occasionally used

in some countries after 1859 as a cheap coinage metal (see above), but

in the later years of the 20th century was replaced by cheaper stainless steel (i.e., iron) alloys, except in the United States and Canada.

Nickel is an excellent alloying agent for certain precious metals and is used in the fire assay as a collector of platinum group elements

(PGE). As such, nickel is capable of fully collecting all six PGE

elements from ores, and of partially collecting gold. High-throughput

nickel mines may also engage in PGE recovery (primarily platinum and palladium); examples are Norilsk in Russia and the Sudbury Basin in Canada.

Nickel and its alloys are frequently used as catalysts for hydrogenation reactions. Raney nickel,

a finely divided nickel-aluminium alloy, is one common form, though

related catalysts are also used, including Raney-type catalysts.

Nickel is a naturally magnetostrictive material, meaning that, in the presence of a magnetic field, the material undergoes a small change in length. The magnetostriction of nickel is on the order of 50 ppm and is negative, indicating that it contracts.

Nickel is used as a binder in the cemented tungsten carbide

or hardmetal industry and used in proportions of 6% to 12% by weight.

Nickel makes the tungsten carbide magnetic and adds corrosion-resistance

to the cemented parts, although the hardness is less than those with a

cobalt binder.

63Ni, with its half-life of 100.1 years, is useful in krytron devices as a beta particle (high-speed electron) emitter to make ionization by the keep-alive electrode more reliable.

Around 27% of all nickel production is destined for engineering,

10% for building and construction, 14% for tubular products, 20% for

metal goods, 14% for transport, 11% for electronic goods, and 5% for

other uses.

Biological role

Although not recognized until the 1970s, nickel is known to play an important role in the biology of some plants, eubacteria, archaebacteria, and fungi. Nickel enzymes such as urease are considered virulence factors in some organisms. Urease catalyzes the hydrolysis of urea to form ammonia and carbamate. The NiFe hydrogenases can catalyze the oxidation of H

2 to form protons and electrons, and can also catalyze the reverse reaction, the reduction of protons to form hydrogen gas. A nickel-tetrapyrrole coenzyme, cofactor F430, is present in methyl coenzyme M reductase, which can catalyze the formation of methane, or the reverse reaction, in methanogenic archaea. One of the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase enzymes consists of an Fe-Ni-S cluster. Other nickel-bearing enzymes include a rare bacterial class of superoxide dismutase and glyoxalase I enzymes in bacteria and several parasitic eukaryotic trypanosomal parasites (in higher organisms, including yeast and mammals, this enzyme contains divalent Zn2+).

2 to form protons and electrons, and can also catalyze the reverse reaction, the reduction of protons to form hydrogen gas. A nickel-tetrapyrrole coenzyme, cofactor F430, is present in methyl coenzyme M reductase, which can catalyze the formation of methane, or the reverse reaction, in methanogenic archaea. One of the carbon monoxide dehydrogenase enzymes consists of an Fe-Ni-S cluster. Other nickel-bearing enzymes include a rare bacterial class of superoxide dismutase and glyoxalase I enzymes in bacteria and several parasitic eukaryotic trypanosomal parasites (in higher organisms, including yeast and mammals, this enzyme contains divalent Zn2+).

Dietary nickel may affect human health through infections by

nickel-dependent bacteria, but it is also possible that nickel is an

essential nutrient for bacteria residing in the large intestine, in

effect functioning as a prebiotic. The U.S. Institute of Medicine has not confirmed that nickel is an essential nutrient for humans, so neither a Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) nor an Adequate Intake have been established. The Tolerable Upper Intake Level

of dietary nickel is 1000 µg/day as soluble nickel salts. Dietary

intake is estimated at 70 to 100 µg/day, with less than 10% absorbed.

What is absorbed is excreted in urine. Relatively large amounts of nickel – comparable to the estimated average ingestion above – leach

into food cooked in stainless steel. For example, the amount of nickel

leached after 10 cooking cycles into one serving of tomato sauce

averages 88 µg.

Nickel released from Siberian Traps volcanic eruptions is suspected of assisting the growth of Methanosarcina, a genus of euryarchaeote archaea that produced methane during the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the biggest extinction event on record.

Toxicity

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS signal word | Danger |

| H317, H351, H372, H412 | |

| P273, P280, P314, P333+313 | |

| NFPA 704 | |

The major source of nickel exposure is oral consumption, as nickel is essential to plants. Nickel is found naturally in both food and water, and may be increased by human pollution. For example, nickel-plated faucets may contaminate water and soil; mining and smelting may dump nickel into waste-water; nickel–steel alloy cookware and nickel-pigmented dishes may release nickel into food. The atmosphere may be polluted by nickel ore refining and fossil fuel combustion. Humans may absorb nickel directly from tobacco smoke and skin contact with jewelry, shampoos, detergents, and coins. A less-common form of chronic exposure is through hemodialysis as traces of nickel ions may be absorbed into the plasma from the chelating action of albumin.

The average daily exposure does not pose a threat to human

health. Most of the nickel absorbed every day by humans is removed by

the kidneys and passed out of the body through urine or is eliminated

through the gastrointestinal tract without being absorbed. Nickel is not

a cumulative poison, but larger doses or chronic inhalation exposure

may be toxic, even carcinogenic, and constitute an occupational hazard.

Nickel compounds are classified as human carcinogens based on increased respiratory cancer risks observed in epidemiological studies of sulfidic ore refinery workers. This is supported by the positive results of the NTP bioassays with Ni sub-sulfide and Ni oxide in rats and mice.

The human and animal data consistently indicate a lack of

carcinogenicity via the oral route of exposure and limit the

carcinogenicity of nickel compounds to respiratory tumours after

inhalation. Nickel metal is classified as a suspect carcinogen;

there is consistency between the absence of increased respiratory

cancer risks in workers predominantly exposed to metallic nickel and the lack of respiratory tumours in a rat lifetime inhalation carcinogenicity study with nickel metal powder.

In the rodent inhalation studies with various nickel compounds and

nickel metal, increased lung inflammations with and without bronchial

lymph node hyperplasia or fibrosis were observed. In rat studies, oral ingestion of water-soluble nickel salts can trigger perinatal mortality effects in pregnant animals.

Whether these effects are relevant to humans is unclear as

epidemiological studies of highly exposed female workers have not shown

adverse developmental toxicity effects.

People can be exposed to nickel in the workplace by inhalation, ingestion, and contact with skin or eye. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has set the legal limit (permissible exposure limit) for the workplace at 1 mg/m3 per 8-hour workday, excluding nickel carbonyl. The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) specifies the recommended exposure limit (REL) of 0.015 mg/m3 per 8-hour workday. At 10 mg/m3, nickel is immediately dangerous to life and health. Nickel carbonyl [Ni(CO)

4] is an extremely toxic gas. The toxicity of metal carbonyls is a function of both the toxicity of the metal and the off-gassing of carbon monoxide from the carbonyl functional groups; nickel carbonyl is also explosive in air.

4] is an extremely toxic gas. The toxicity of metal carbonyls is a function of both the toxicity of the metal and the off-gassing of carbon monoxide from the carbonyl functional groups; nickel carbonyl is also explosive in air.

Sensitized individuals may show a skin contact allergy to nickel known as a contact dermatitis. Highly sensitized individuals may also react to foods with high nickel content. Sensitivity to nickel may also be present in patients with pompholyx. Nickel is the top confirmed contact allergen worldwide, partly due to its use in jewelry for pierced ears.

Nickel allergies affecting pierced ears are often marked by itchy, red

skin. Many earrings are now made without nickel or low-release nickel to address this problem. The amount allowed in products that contact human skin is now regulated by the European Union.

In 2002, researchers found that the nickel released by 1 and 2 Euro

coins was far in excess of those standards. This is believed to be the

result of a galvanic reaction. Nickel was voted Allergen of the Year in 2008 by the American Contact Dermatitis Society.

In August 2015, the American Academy of Dermatology adopted a position

statement on the safety of nickel: "Estimates suggest that contact

dermatitis, which includes nickel sensitization, accounts for

approximately $1.918 billion and affects nearly 72.29 million people."

Reports show that both the nickel-induced activation of

hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1) and the up-regulation of

hypoxia-inducible genes are caused by depletion of intracellular ascorbate.

The addition of ascorbate to the culture medium increased the

intracellular ascorbate level and reversed both the metal-induced

stabilization of HIF-1- and HIF-1α-dependent gene expression.