While macroeconomics is a broad field of study, there are two areas of research that are emblematic of the discipline: the attempt to understand the causes and consequences of short-run fluctuations in national income (the business cycle), and the attempt to understand the determinants of long-run economic growth (increases in national income). Macroeconomic models and their forecasts are used by governments to assist in the development and evaluation of economic policy.

Macroeconomics and microeconomics, a pair of terms coined by Ragnar Frisch, are the two most general fields in economics. In contrast to macroeconomics, microeconomics is the branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions and the interactions among these individuals and firms in narrowly-defined markets.

Basic macroeconomic concepts

Macroeconomics encompasses a variety of concepts and variables, but there are three central topics for macroeconomic research.

Macroeconomic theories usually relate the phenomena of output,

unemployment, and inflation. Outside of macroeconomic theory, these

topics are also important to all economic agents including workers,

consumers, and producers.

Output and income

National output

is the total amount of everything a country produces in a given period

of time. Everything that is produced and sold generates an equal amount

of income. The total output of the economy is measured GDP per person.

The output and income are usually considered equivalent and the two

terms are often used interchangeably,output changes into income. Output

can be measured or it can be viewed from the production side and

measured as the total value of final goods and services or the sum of all value added in the economy.

Macroeconomic output is usually measured by gross domestic product (GDP) or one of the other national accounts.

Economists interested in long-run increases in output study economic

growth. Advances in technology, accumulation of machinery and other capital, and better education and human capital

are all factors that lead to increased economic output over time.

However, output does not always increase consistently over time. Business cycles can cause short-term drops in output called recessions. Economists look for macroeconomic policies that prevent economies from slipping into recessions and that lead to faster long-term growth.

Unemployment

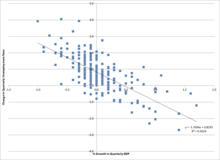

A chart using US data showing the relationship between economic growth and unemployment expressed by Okun's law. The relationship demonstrates cyclical unemployment. Economic growth leads to a lower unemployment rate.

The amount of unemployment in an economy is measured by the unemployment rate, i.e. the percentage of workers without jobs in the labor force.

The unemployment rate in the labor force only includes workers actively

looking for jobs. People who are retired, pursuing education, or discouraged from seeking work by a lack of job prospects are excluded.

Unemployment can be generally broken down into several types that are related to different causes.

- Classical unemployment theory suggests that unemployment occurs when wages are too high for employers to be willing to hire more workers. Other more modern economic theories suggest that increased wages actually decrease unemployment by creating more consumer demand. According to these more recent theories, unemployment results from reduced demand for the goods and services produced through labor and suggest that only in markets where profit margins are very low, and in which the market will not bear a price increase of product or service, will higher wages result in unemployment.

- Consistent with classical unemployment theory, frictional unemployment occurs when appropriate job vacancies exist for a worker, but the length of time needed to search for and find the job leads to a period of unemployment.

- Structural unemployment covers a variety of possible causes of unemployment including a mismatch between workers' skills and the skills required for open jobs. Large amounts of structural unemployment commonly occur when an economy shifts to focus on new industries and workers find their previous set of skills are no longer in demand. Structural unemployment is similar to frictional unemployment as both reflect the problem of matching workers with job vacancies, but structural unemployment also covers the time needed to acquire new skills in addition to the short-term search process.

- While some types of unemployment may occur regardless of the condition of the economy, cyclical unemployment occurs when growth stagnates. Okun's law represents the empirical relationship between unemployment and economic growth. The original version of Okun's law states that a 3% increase in output would lead to a 1% decrease in unemployment.

Inflation and deflation

The

ten-year moving averages of changes in price level and growth in money

supply (using the measure of M2, the supply of hard currency and money

held in most types of bank accounts) in the US from 1875 to 2011. Over

the long run, the two series show a close relationship.

A general price increase across the entire economy is called inflation. When prices decrease, there is deflation. Economists measure these changes in prices with price indexes.

Inflation can occur when an economy becomes overheated and grows too

quickly. Similarly, a declining economy can lead to deflation.

Central bankers, who manage a country's money supply, try to avoid changes in price level by using monetary policy.

Raising interest rates or reducing the supply of money in an economy

will reduce inflation. Inflation can lead to increased uncertainty and

other negative consequences. Deflation can lower economic output.

Central bankers try to stabilize prices to protect economies from the

negative consequences of price changes.

Changes in price level may be the result of several factors. The quantity theory of money holds that changes in price level are directly related to changes in the money supply. Most economists believe that this relationship explains long-run changes in the price level.

Short-run fluctuations may also be related to monetary factors, but

changes in aggregate demand and aggregate supply can also influence

price level. For example, a decrease in demand due to a recession can

lead to lower price levels and deflation. A negative supply shock, such

as an oil crisis, lowers aggregate supply and can cause inflation.

Macroeconomic models

Aggregate demand–aggregate supply

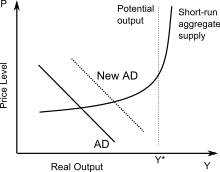

A traditional AS–AD diagram showing a shift in AD and the AS curve becoming inelastic beyond potential output.

The AD-AS model has become the standard textbook model for explaining the macroeconomy. This model shows the price level and level of real output given the equilibrium in aggregate demand and aggregate supply. The aggregate demand curve's downward slope means that more output is demanded at lower price levels. The downward slope is the result of three effects: the Pigou or real balance effect, which states that as real prices fall, real wealth increases, resulting in higher consumer demand of goods; the Keynes or interest rate effect,

which states that as prices fall, the demand for money decreases,

causing interest rates to decline and borrowing for investment and

consumption to increase; and the net export effect, which states that as

prices rise, domestic goods become comparatively more expensive to

foreign consumers, leading to a decline in exports.

In the conventional Keynesian use of the AS-AD model, the

aggregate supply curve is horizontal at low levels of output and becomes

inelastic near the point of potential output, which corresponds with full employment.

Since the economy cannot produce beyond the potential output, any AD

expansion will lead to higher price levels instead of higher output.

The AD–AS diagram can model a variety of macroeconomic phenomena,

including inflation. Changes in the non-price level factors or

determinants cause changes in aggregate demand and shifts of the entire

aggregate demand (AD) curve. When demand for goods exceeds supply there

is an inflationary gap where demand-pull inflation occurs and the AD curve shifts upward to a higher price level. When the economy faces higher costs, cost-push inflation occurs and the AS curve shifts upward to higher price levels. The AS–AD diagram is also widely used as a pedagogical tool to model the effects of various macroeconomic policies.

IS-LM

In

this example of an IS/LM chart, the IS curve moves to the right,

causing higher interest rates (i) and expansion in the "real" economy

(real GDP, or Y).

The IS–LM

model gives the underpinnings of aggregate demand (itself discussed

above). It answers the question “At any given price level, what is the

quantity of goods demanded?” This model shows represents what

combination of interest rates and output will ensure equilibrium in both

the goods and money markets.

The goods market is modeled as giving equality between investment and

public and private saving (IS), and the money market is modeled as

giving equilibrium between the money supply and liquidity preference.

The IS curve consists of the points (combinations of income and

interest rate) where investment, given the interest rate, is equal to

public and private saving, given output.

The IS curve is downward sloping because output and the interest rate

have an inverse relationship in the goods market: as output increases,

more income is saved, which means interest rates must be lower to spur

enough investment to match saving.

The LM curve is upward sloping because the interest rate and

output have a positive relationship in the money market: as income

(identically equal to output) increases, the demand for money increases,

resulting in a rise in the interest rate in order to just offset the

insipient rise in money demand.

The IS-LM model is often used to demonstrate the effects of monetary and fiscal policy. Textbooks frequently use the IS-LM model, but it does not feature the complexities of most modern macroeconomic models. Nevertheless, these models still feature similar relationships to those in IS-LM.

Growth models

The neoclassical growth model of Robert Solow has become a common textbook model for explaining economic growth in the long-run. The model begins with a production function

where national output is the product of two inputs: capital and labor.

The Solow model assumes that labor and capital are used at constant

rates without the fluctuations in unemployment and capital utilization

commonly seen in business cycles.

An increase in output, or economic growth, can only occur because

of an increase in the capital stock, a larger population, or

technological advancements that lead to higher productivity (total factor productivity).

An increase in the savings rate leads to a temporary increase as the

economy creates more capital, which adds to output. However, eventually

the depreciation rate will limit the expansion of capital: savings will

be used up replacing depreciated capital, and no savings will remain to

pay for an additional expansion in capital. Solow's model suggests that

economic growth in terms of output per capita depends solely on

technological advances that enhance productivity.

In the 1980s and 1990s endogenous growth theory

arose to challenge neoclassical growth theory. This group of models

explains economic growth through other factors, such as increasing

returns to scale for capital and learning-by-doing, that are endogenously determined instead of the exogenous technological improvement used to explain growth in Solow's model.

Macroeconomic policy

Macroeconomic

policy is usually implemented through two sets of tools: fiscal and

monetary policy. Both forms of policy are used to stabilize the economy, which can mean boosting the economy to the level of GDP consistent with full employment.

Macroeconomic policy focuses on limiting the effects of the business

cycle to achieve the economic goals of price stability, full employment,

and growth.

Monetary policy

Central banks implement monetary policy by controlling the money

supply through several mechanisms. Typically, central banks take action

by issuing money to buy bonds (or other assets), which boosts the supply

of money and lowers interest rates, or, in the case of contractionary

monetary policy, banks sell bonds and take money out of circulation.

Usually policy is not implemented by directly targeting the supply of

money.

Central banks continuously shift the money supply to maintain a

targeted fixed interest rate. Some of them allow the interest rate to

fluctuate and focus on targeting inflation rates

instead. Central banks generally try to achieve high output without

letting loose monetary policy that create large amounts of inflation.

Conventional monetary policy can be ineffective in situations such as a liquidity trap. When interest rates and inflation are near zero, the central bank cannot loosen monetary policy through conventional means.

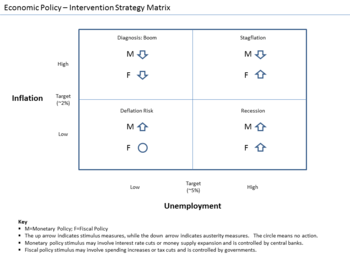

An example of intervention strategy under different conditions

Central banks can use unconventional monetary policy such as quantitative easing

to help increase output. Instead of buying government bonds, central

banks can implement quantitative easing by buying not only government

bonds, but also other assets such as corporate bonds, stocks, and other

securities. This allows lower interest rates for a broader class of

assets beyond government bonds. In another example of unconventional

monetary policy, the United States Federal Reserve recently made an

attempt at such a policy with Operation Twist.

Unable to lower current interest rates, the Federal Reserve lowered

long-term interest rates by buying long-term bonds and selling

short-term bonds to create a flat yield curve.

Fiscal policy

Fiscal policy is the use of government's revenue and expenditure as

instruments to influence the economy. Examples of such tools are expenditure, taxes, debt.

For example, if the economy is producing less than potential

output, government spending can be used to employ idle resources and

boost output. Government spending does not have to make up for the

entire output gap. There is a multiplier effect

that boosts the impact of government spending. For instance, when the

government pays for a bridge, the project not only adds the value of the

bridge to output, but also allows the bridge workers to increase their

consumption and investment, which helps to close the output gap.

The effects of fiscal policy can be limited by crowding out.

When the government takes on spending projects, it limits the amount of

resources available for the private sector to use. Crowding out occurs

when government spending simply replaces private sector output instead

of adding additional output to the economy. Crowding out also occurs

when government spending raises interest rates, which limits investment.

Defenders of fiscal stimulus argue that crowding out is not a concern

when the economy is depressed, plenty of resources are left idle, and

interest rates are low.

Fiscal policy can be implemented through automatic stabilizers.

Automatic stabilizers do not suffer from the policy lags of

discretionary fiscal policy. Automatic stabilizers use conventional

fiscal mechanisms but take effect as soon as the economy takes a

downturn: spending on unemployment benefits automatically increases when

unemployment rises and, in a progressive income tax system, the

effective tax rate automatically falls when incomes decline.

Comparison

Economists

usually favor monetary over fiscal policy because it has two major

advantages. First, monetary policy is generally implemented by

independent central banks instead of the political institutions that

control fiscal policy. Independent central banks are less likely to make

decisions based on political motives. Second, monetary policy suffers shorter inside lags and outside lags

than fiscal policy. Central banks can quickly make and implement

decisions while discretionary fiscal policy may take time to pass and

even longer to carry out.

Development

Origins

Macroeconomics descended from the once divided fields of business cycle theory and monetary theory. The quantity theory of money was particularly influential prior to World War II. It took many forms, including the version based on the work of Irving Fisher:

In the typical view of the quantity theory, money velocity (V) and the quantity of goods produced (Q) would be constant, so any increase in money supply

(M) would lead to a direct increase in price level (P). The quantity

theory of money was a central part of the classical theory of the

economy that prevailed in the early twentieth century.

Austrian School

Ludwig Von Mises's work Theory of Money and Credit, published in 1912, was one of the first books from the Austrian School to deal with macroeconomic topics.

Keynes and his followers

Macroeconomics, at least in its modern form, began with the publication of John Maynard Keynes's General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.

When the Great Depression struck, classical economists had difficulty

explaining how goods could go unsold and workers could be left

unemployed. In classical theory, prices and wages would drop until the

market cleared, and all goods and labor were sold. Keynes offered a new

theory of economics that explained why markets might not clear, which

would evolve (later in the 20th century) into a group of macroeconomic

schools of thought known as Keynesian economics – also called Keynesianism or Keynesian theory.

In Keynes's theory, the quantity theory broke down because people

and businesses tend to hold on to their cash in tough economic times – a

phenomenon he described in terms of liquidity preferences. Keynes also explained how the multiplier effect

would magnify a small decrease in consumption or investment and cause

declines throughout the economy. Keynes also noted the role uncertainty

and animal spirits can play in the economy.

The generation following Keynes combined the macroeconomics of the General Theory with neoclassical microeconomics to create the neoclassical synthesis. By the 1950s, most economists had accepted the synthesis view of the macroeconomy. Economists like Paul Samuelson, Franco Modigliani, James Tobin, and Robert Solow

developed formal Keynesian models and contributed formal theories of

consumption, investment, and money demand that fleshed out the Keynesian

framework.

Monetarism

Milton Friedman

updated the quantity theory of money to include a role for money

demand. He argued that the role of money in the economy was sufficient

to explain the Great Depression,

and that aggregate demand oriented explanations were not necessary.

Friedman also argued that monetary policy was more effective than fiscal

policy; however, Friedman doubted the government's ability to

"fine-tune" the economy with monetary policy. He generally favored a

policy of steady growth in money supply instead of frequent

intervention.

Friedman also challenged the Phillips curve relationship between inflation and unemployment. Friedman and Edmund Phelps

(who was not a monetarist) proposed an "augmented" version of the

Phillips curve that excluded the possibility of a stable, long-run

tradeoff between inflation and unemployment. When the oil shocks

of the 1970s created a high unemployment and high inflation, Friedman

and Phelps were vindicated. Monetarism was particularly influential in

the early 1980s. Monetarism fell out of favor when central banks found

it difficult to target money supply instead of interest rates as

monetarists recommended. Monetarism also became politically unpopular

when the central banks created recessions in order to slow inflation.

New classical

New classical macroeconomics further challenged the Keynesian school. A central development in new classical thought came when Robert Lucas introduced rational expectations to macroeconomics. Prior to Lucas, economists had generally used adaptive expectations

where agents were assumed to look at the recent past to make

expectations about the future. Under rational expectations, agents are

assumed to be more sophisticated. A consumer will not simply assume a 2%

inflation rate just because that has been the average the past few

years; she will look at current monetary policy and economic conditions

to make an informed forecast. When new classical economists introduced

rational expectations into their models, they showed that monetary

policy could only have a limited impact.

Lucas also made an influential critique

of Keynesian empirical models. He argued that forecasting models based

on empirical relationships would keep producing the same predictions

even as the underlying model generating the data changed. He advocated

models based on fundamental economic theory that would, in principle, be

structurally accurate as economies changed. Following Lucas's critique,

new classical economists, led by Edward C. Prescott and Finn E. Kydland, created real business cycle (RBC) models of the macroeconomy.

RBC models were created by combining fundamental equations from

neo-classical microeconomics. In order to generate macroeconomic

fluctuations, RBC models explained recessions and unemployment with

changes in technology instead of changes in the markets for goods or

money. Critics of RBC models argue that money clearly plays an important

role in the economy, and the idea that technological regress can

explain recent recessions is implausible.

However, technological shocks are only the more prominent of a myriad

of possible shocks to the system that can be modeled. Despite questions

about the theory behind RBC models, they have clearly been influential

in economic methodology.

New Keynesian response

New Keynesian

economists responded to the new classical school by adopting rational

expectations and focusing on developing micro-founded models that are

immune to the Lucas critique. Stanley Fischer and John B. Taylor

produced early work in this area by showing that monetary policy could

be effective even in models with rational expectations when contracts

locked in wages for workers. Other new Keynesian economists, including Olivier Blanchard, Julio Rotemberg, Greg Mankiw, David Romer, and Michael Woodford,

expanded on this work and demonstrated other cases where inflexible

prices and wages led to monetary and fiscal policy having real effects.

Like classical models, new classical models had assumed that

prices would be able to adjust perfectly and monetary policy would only

lead to price changes. New Keynesian models investigated sources of sticky prices and wages due to imperfect competition, which would not adjust, allowing monetary policy to impact quantities instead of prices.

By the late 1990s economists had reached a rough consensus. The

nominal rigidity of new Keynesian theory was combined with rational

expectations and the RBC methodology to produce dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) models. The fusion of elements from different schools of thought has been dubbed the new neoclassical synthesis. These models are now used by many central banks and are a core part of contemporary macroeconomics.

New Keynesian economics, which developed partly in response to

new classical economics, strives to provide microeconomic foundations to

Keynesian economics by showing how imperfect markets can justify demand

management.